The work of the famous French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is made up of glances, of moments captured at the wrong moment or mistakes made at the right time. It surely stems from a deep and enduring connection with Italy, from a keen eye for squares, streets and a unique ability to capture the invisible essence of the everyday. This is how Clément Chéroux, photography historian and curator of the exhibition Henri Cartier-Bresson and Italy at Rovigo’s Palazzo Roverella, describes with rare passion the photographs before him. The Italian shots became, during our conversation, an invaluable opportunity to explore the symbolic and cultural significance of Cartier-Bresson’s work, his connection to Paris surrealist circles, the evolution of his style and the ability of his images to narrate not only Italy, but the human condition in its elusive totality. Here is what Clément Chéroux confided to us on the sidelines of the exhibition opening. The interview is by Francesca Gigli.

FG. Cartier-Bresson, starting with painting under the guidance of André Lhote, later embraced photography, a crucial change influenced by his travels and Mediterranean and Latin cultures, particularly that of Italy. How did your visual and cultural experiences, gained during these travels, transform your approach to photographic composition? And how did collaborations with international magazines such as Holiday or Vogue help shape and spread the world’s view of Italy through your unique gaze ?

CC. In the 1920s, Cartier-Bresson underwent two fundamental influences: the first was that of André Lhote and his Academy, where he learned Cubist techniques and developed a deep pleasure in geometric forms; the second, equally crucial, was the influence of Surrealism, thanks to his closeness to André Breton and other exponents of this movement. From them he acquired the importance of chance and surprise, and it was precisely these two strands that mingled with quiet balance in his photographs of the 1930s: on the one hand, there is a rigorous geometric organization; on the other, an element always emerges that disrupts the image, creating visual tension. It is essential, then, to understand how there can be no single “style” of Cartier-Bresson, but his way of photographing constantly evolves over the forty years he devoted himself to photography, his images transform over time, shaping his own world, and we can distinguish different phases in his production, as happens with every great artist. In the photographs made during his first trip to Italy in the 1930s, for example, the Surrealist influence is more strongly perceived; on the contrary, in the postwar images, after the founding of the Magnum agency in 1947, we see a greater mastery and control of composition, with less of a role left to chance. As for his collaborations with magazines such as Holiday and Vogue, on the other hand, Cartier-Bresson certainly contributed to shaping the image of Italy in the world as his unique gaze, combined with his ability to capture the essence of places and people, allowed him to spread a vision of a country in which beauty, ugliness, mystery and unpredictability coexist harmoniously as the two souls of the photographer.

About the Surrealist circles that Cartier-Bresson frequented in Paris, in particular to the figures of André Breton and René Crevel. How did this Surrealist influence help shape his photographic style and the concept of the “decisive moment”?

Cartier-Bresson was introduced to surrealist circles through his friendship with the poet René Crevel, and this proved to be a crucial encounter for his artistic growth. By associating with the Surrealists, the photographer absorbed a key concept that would profoundly mark his work: the importance of chance, the unexpected, the unexpected that emerges in reality. While in André Lhote’s atelier he had learned the discipline of formal control and compositional precision, within the Surrealist movement he learned to value random elements, those that escape the planning of the mind. I think the greatness of his photography lies precisely in this fusion of two seemingly opposing approaches in which on the one hand dwells the mastery of technique and composition and on the other, an openness to randomness and chaos. In each shot, Cartier-Bresson combined that geometric rigor with the irruption of chance, making a subtle tension between order and chaos manifest in his images. It is from this dynamic that the concept of the “decisive moment” was born, that unrepeatable instant in which all the elements align perfectly, and in which the photographer must be ready to capture the essence of a scene and nothing else. The Surrealist influence taught him to see beyond visible reality, to capture those unexpected details that give photography a unique poetic and narrative force, and this continuous balance between control and improvisation became the hallmark of his style, making his work immortal and recognizable.

Cartier-Bresson’s first trip to Italy comes at a time of transition in his life: is it possible that the feeling of feeling “lost” or “searching for direction” may have enriched his creative journey? How important do you think it is to embrace uncertainty in the process of redefining one’s path?

Certainly, Cartier-Bresson’s first trip to Italy was part of a crucial moment in his life marked by a personal and artistic quest. Initially he was eager to become a painter, but he found himself discovering photography just before this trip in which he devoted himself to taking a few images, almost like any tourist. One aspect of great interest was precisely the purchase of his first Leica in 1932, a light and handy camera that revolutionized his approach to photography. With this tool, Cartier-Bresson developed the concept of the “decisive moment,” the belief that a photograph should be captured in a precise instant, neither before nor after. After experimenting with the new Leica in the south of France, a trip to Italy represented an opportunity to concretely apply his artistic vision, and the Mediterranean light, along with the country’s evocative atmospheres, became the ideal context for exploring his new medium and refining his shots. The compactness and practicality of the Leica, moreover, allowed him to be always ready to capture the perfect moment. This unobtrusive and lightweight tool became an extension of his eye, allowing him to move with agility among people and places, without losing sight of those unique and unrepeatable moments that characterize many of his works. It might be very fascinating today to reflect on how, during that period of transition and perhaps uncertainty, his interaction with Leica and his experience in Italy helped to delineate his photographic poetics, based on immediacy and visual intuition.

Italy seems to have exerted a profound influence on Cartier-Bresson’s career. How do you think the effervescence of Italian life, particularly that which takes place among the streets, shaped his development as a photographer and his love of street photography?

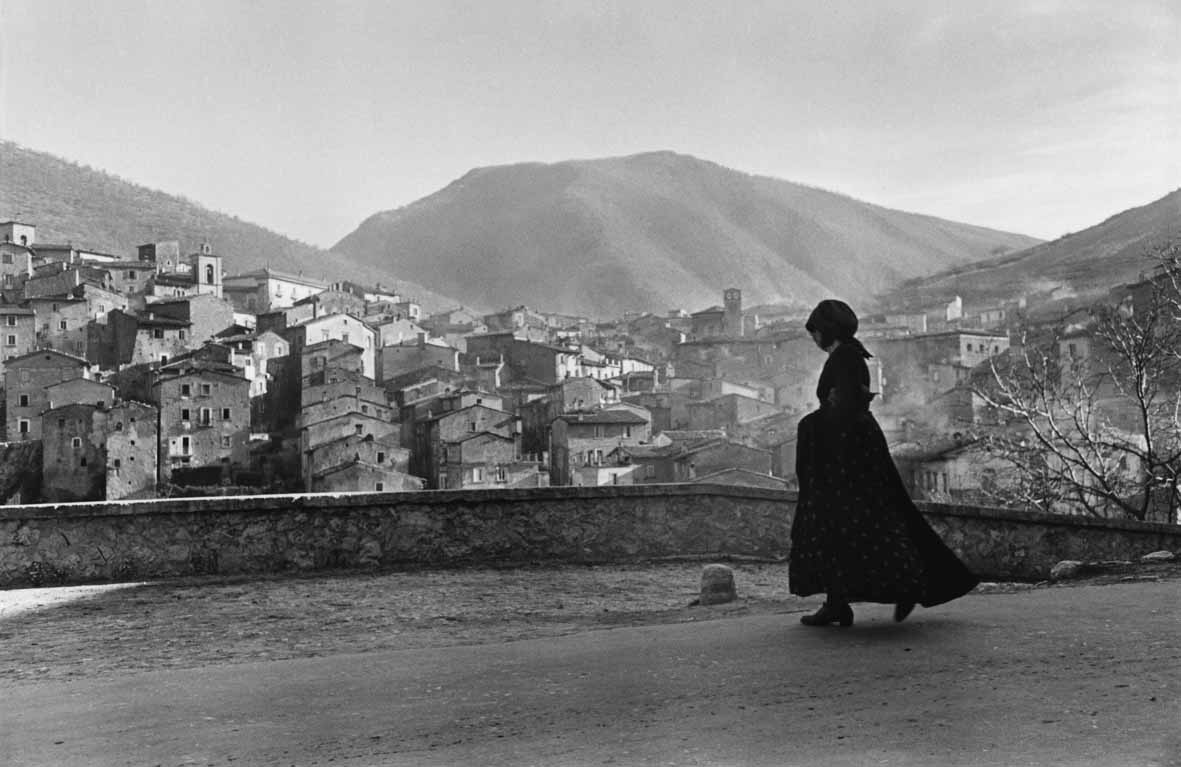

A key aspect of Cartier-Bresson’s connection with Italy is the vitality that permeated street life, an element that had a crucial impact on his photography. Italy, as well as other Mediterranean and Latin countries such as Spain and Mexico, is a place where daily life takes place mostly outdoors, in piazzas, alleys and streets. His photographs from the 1930s, taken during his travels in these nations, testify to his ability to capture the unpredictability of human flow, where people come and go, creating a continuous movement that enriches and transforms the photographic scene. Unlike other photographers of the time, who used cumbersome cameras on tripods and required subjects to pose statically, Cartier-Bresson, with his Leica, moved nimbly among people, capturing the spirit of life in constant turmoil. His small, handy camera allowed him to be unobtrusive, almost invisible, as he captured spontaneous and natural scenes. And it was this new photographic approach of his, characterized by the frenetic activity of the streets and the effervescence of urban life, that represented a break with the past and ushered in a new era in the history of photography. Italy, with its wealth of unexpected situations and the constant pulsing of outdoor life, was for Cartier-Bresson a privileged place to put this vision into practice. The constant chaos of the Italian streets, with the constant alternation of people and moments, gave shape to a unique photographic style, capable of blending composition and spontaneity, where the unexpected becomes an integral part of the work. It is precisely this effervescence, this continuous flow of life, that helped make Cartier-Bresson one of the undisputed masters of street photography.

Cartier-Bresson returned frequently to Italy until the 1970s, not only for professional reasons but also to visit museums and devote himself to drawing, inspired by the works of the great Renaissance masters. Do you think his interest in Renaissance art influenced the way he composed photographic images?

A hallmark of Cartier-Bresson is his extraordinary situational intelligence, the ability to arrive at a place and immediately understand how things are organized, both visually and socially. This talent translates into his ability to find photographic forms that reflect the essence of his surroundings.

His interest in the great masters of the Italian Renaissance has certainly influenced his way of composing images: his attention to geometry, harmony of form and proportion, pivotal elements of Renaissance art, are also found in his photographs, where the structure of the image follows a strict formal balance. His affinity with Renaissance art has allowed him to transpose, in his photographic works, a compositional vision in which order and classical aesthetics merge with the immediacy of everyday life. Italy, with its rich artistic heritage and the vitality of its piazzas, offered Cartier-Bresson the opportunity to exercise his critical eye and perfect his technique, making his photography a medium through which to explore and immortalize the social and urban complexity of the places he deeply loved.

Cartier-Bresson produced a reportage for “Life” focusing on the importance of Italian piazzas in urban culture. What is the symbolic significance of piazzas in his work and how do they reflect Italian life in those years?

Cartier-Bresson, with his reportage for Life dedicated to Italian piazzas, captured a profoundly symbolic aspect of the country’s urban culture: the piazzas as the fulcrum of social and community life. For Cartier-Bresson, the Italian piazza represented not only a physical place, but also a space of encounter, interaction and collective narrative, where the dynamism of daily life unfolds in all its richness. In his vision, the piazza was a natural stage where people moved in a spontaneous and continuous spectacle, embodying the concept of the “decisive moment” that defined his photography in which every moment captured among the Italian streets and piazzas was unique and unrepeatable, thanks to the constant vitality that characterized these places: passers-by arriving and departing, children playing, street vendors, tourists and locals crossing in an uninterrupted flow. Squares, for Cartier-Bresson, were not mere stage sets, but true microcosms of society, mirrors of a culture that celebrated sociality and collective living. Precisely for this reason, his are not just images that document, but enhance the essence of Italian life, made up of encounters, dialogues and quiet moments. It is interesting, for example, to note how Cartier-Bresson was able to perfectly capture the differences between European and U.S. urban and social organization: in Europe, and particularly in Italy, everything revolves around the piazza, a place where people stop, live and interact; on the contrary, in the United States, mobility is at the center of urban organization, everything develops along Main Street, where people do not stop, but pass by. And Cartier-Bresson, with his acute sensitivity, was able to represent these differences through his photography, reflecting deeply on the importance of the square as a place for meeting, stopping and socializing, especially in Italy.

During the photographer’s lifetime , no volume has ever been published about his travels to Italy, unlike other countries, such as the United States or India. Why do you think Italy took a back seat in publications during his career, despite its importance to the photographer?

It is true that Cartier-Bresson photographed a great deal in Italy, over a period of time from the 1930s to the 1970s, and probably, Italy is one of the countries where he took the most images throughout his career. However, it remains an enigma that a volume dedicated specifically to this country has never been published, although books have been produced on other nations such as Mexico, the United States or India. It is difficult for me to fully understand the reasons for this lack, but it could be that Cartier-Bresson accumulated shots of Italy so deeply that he felt overwhelmed by the vastness of the material he had collected. Perhaps, precisely because he photographed so much of this country, he was unable to select and organize the images for a publication, fearing that the work was too large and complex. Or, it is possible that his emotional connection to the country led him to postpone this project, precisely because of its personal significance. In any case, it is cause for great satisfaction that, with this exhibition, what has been a significant gap is finally being filled. This exhibition represents, in fact, the first occasion in which Italy is celebrated as one of the central places in Cartier-Bresson’s artistic production, restoring to the public the immense richness and intensity of his gaze on this country that he loved so much.

Throughout his career, Cartier-Bresson took very few self-portraits and rarely ventured into nude photography. However, these themes seem to emerge almost exclusively during his Italian period. What do you think is the reason for this choice and why were such subjects so rarely treated?

During his career, Cartier-Bresson made very few self-portraits and rare nude photographs, but his first trip to Italy was a significant exception to this as well. It was during this period, in fact, that he created not only a rare self-portrait, but also a number of nude photographs, such as those taken in Trieste in 1933, depicting André Pieyre de Mandiargues and Leonor Fini immersed in water. These images embody an extraordinary sense of freedom, symbolic of what Cartier-Bresson felt during his stay. This trip was a discovery for him, not only of a new country, but also of the small tool that would revolutionize his photographic approach and allow him to experiment with great spontaneity. Unencumbered, he devoted himself entirely to capturing images without any constraints, thoroughly enjoying those Italian months to explore new ideas, forms and perspectives. The creative freedom he experienced during that period led him to experiment with themes and subjects that he later dealt with much less frequently in the rest of his career.

Looking at his Italian self-portrait from 1932, I found myself reflecting on my belief that Cartier-Bresson had only come to Italy in 1933. Could you then confirm the existence of a dating error concerning his stay in this country? How did you discover this?

Exactly, in preparing this exhibition, we discovered a dating error that led to a revision of the period when Cartier-Bresson took some of his first photographs. Initially, these images, including the self-portrait of feet, were thought to have been taken in 1933. However, rereading the correspondence between Cartier-Bresson and his writer friend André-Pierre de Mandiargues, as well as letters exchanged with Italian artists, we realized that the trip took place in the summer of 1932. This self-portrait of the feet, moreover, is a rare and significant choice that on the one hand, represents Cartier-Bresson’s desire to remain invisible, as if to remove his face from the photographic context and let the image speak exclusively, while on the other hand, it shows us the photographer in a moment of deep reflection on his journey: the focus is not on himself, but on the gesture, the movement and the road he travels. Cartier-Bresson did not want to be the protagonist of his works, but rather wished to capture the world through his gaze, letting the image and the moment take center stage.

In your essay “photographic error,” you describe error as an opportunity for creative wandering. To what extent does this “going errant” foster a more authentic and surprising photography than a codified and standardized production?

As I recounted earlier, the influence of surrealism, which Cartier-Bresson absorbed by frequenting Parisian circles around André Breton, played a crucial role in his approach to photography. And so, too, the concept of “error,” typical of Surrealism, is reflected in the practice of urban wandering, of walking without a precise destination, allowing oneself to be surprised by the unexpected. In this sense, the error or the unexpected is not seen as an obstacle, but becomes a creative opportunity. Cartier-Bresson, in line with this philosophy, did not try to plan every detail of his shots; on the contrary, he let himself be carried away by the randomness of life, by chance encounters with people or situations he had not anticipated. This “going errant” allowed him to capture authentic images, charged with spontaneity and originality, that could never have come from a rigidly codified or standardized production.

He also mentioned in his book that an errant image can serve as a key to knowledge. Can you elaborate on how photographic error can facilitate ourunderstanding of the world or our perception? Did Cartier-Bresson ever make one of these “mistakes”?

I think the question of chance is crucial to understanding Cartier-Bresson’s approach to photography. Chance, as he learned from the Surrealist movement, can yield both positive and negative outcomes: it can lead to a successful photograph or a less successful one. This unpredictable element is at the heart of his photographic practice. An emblematic example is found in one of the rooms of the exhibition Henri Cartier-Bresson and Italy, where we see an image Cartier-Bresson took of a priest as he passes in front of a column; in the image, however, an unplanned, out-of-focus figure appears in the foreground, crossing the scene. According to traditional canons of photography, this would be considered an error, a disturbance in the composition, however, Cartier-Bresson decided to preserve the image precisely because of this unexpected element. He recognized that despite the randomness of that intervention, something visually interesting emerged from the triangulation between the priest, the column and the blurred figure. This episode shows how the mistake, for Cartier-Bresson, was not simply a technical flaw, but an opportunity to discover new visual possibilities.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.