From January 18 to April 27, 2025, the exhibition Giacinto Cerone is on view at the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza. The Necessary Angel, an anthological exhibition dedicated to Giacinto Cerone (Melfi, 1957 - Rome, 2004), a singular sculptor with a short career who worked free from groups, schools and movements, marking one of the most singular experiences of the second half of the 20th century in Italian sculpture. The exhibition, in particular, explores Cerone’s connection with ceramics and, more specifically, with Faenza: the very title, The Necessary Angel, refers to a figure described by the American poet Wallace Stevens that often returns in Cerone’s statuary. Curated by Marco Tonelli (Rome, 1971), an art critic and historian, the exhibition intends not only to trace Cerone’s relationship with Faenza, but also to delineate his figure and relocate him in the context of the Italian arts of the second half of the 20th century. We talked about it with Marco Tonelli, the interview is by Noemi Capoccia.

NC. What importance did Faenza have in Giacinto Cerone’s artistic journey, and how did his experiments with ceramics transform his sculpture?

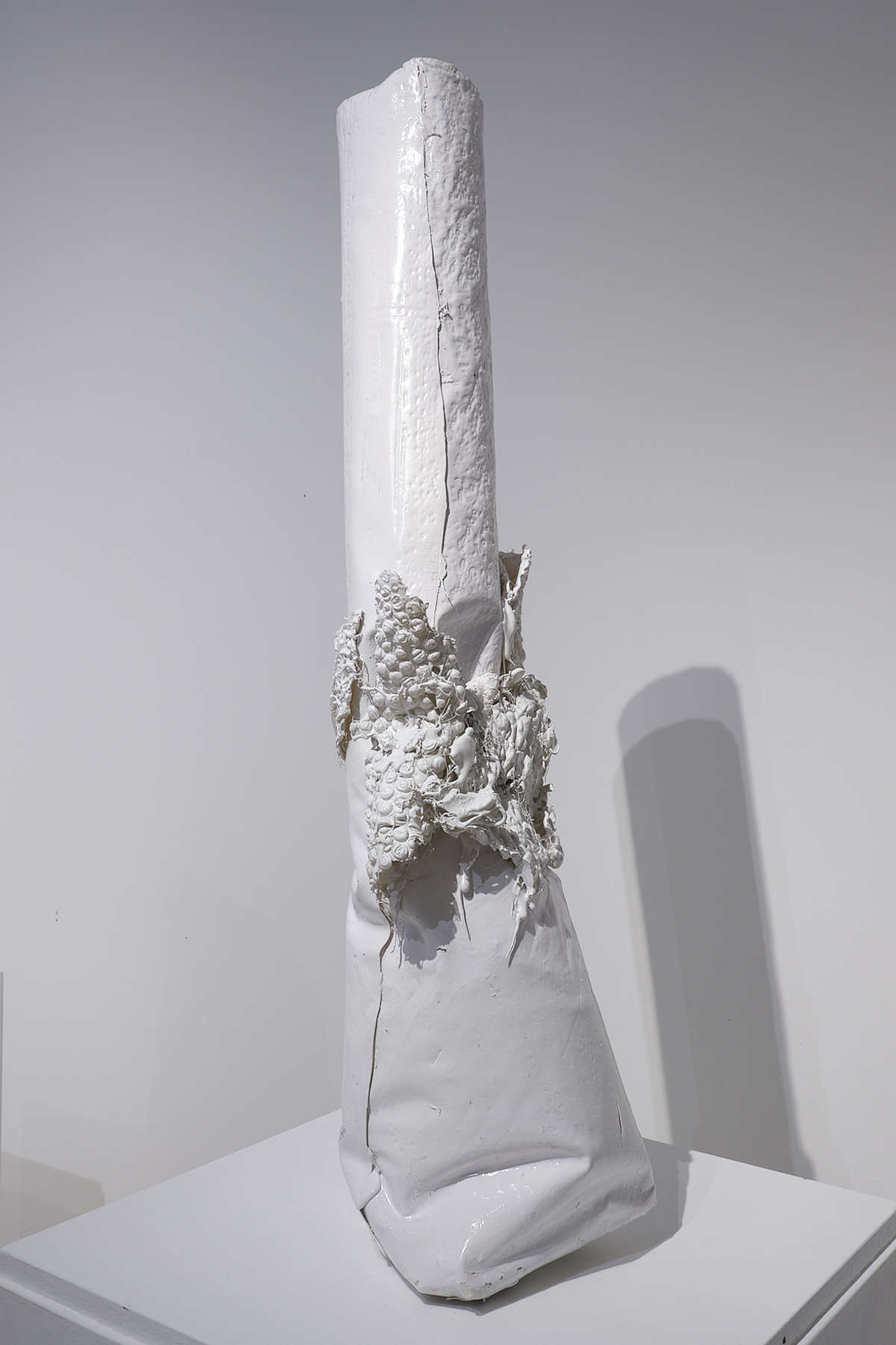

MT. Since 1993 Giacinto Cerone began working with ceramics, flanked by Davide Servadei of Ceramiche Gatti, a key reference figure. It was not the first time he was confronted with this material, having already made ceramic works in other places in Italy, such as in Albissola. In any case, in Faenza he found a different context, thanks in part to his collaboration with a technician with an extraordinary artistic sensibility, capable of interpreting his needs and style. The technician, in the course of time, perfects materials and colors, adapting them more and more to the expressive modes of Cerone, who until then had worked mainly with wood and plaster. Ceramics in Faenza, became an ideal material for him, treated with the same physical energy and intensity he reserved for other media. Here, thanks to clay modules specially prepared by Servadei, he developed an almost brutal approach: columns bent, slashed, kicked, struck with violence. All this gave rise to works of extraordinary gestural force. Also emerging were richer, more elaborate ceramics charged with symbolic meanings, sometimes with a mortuary vein, others of sumptuous and refined beauty. Faenza is where Cerone’s ceramic art is fully defined, while maintaining a distance from the traditional figure of the potter. In this context, Cerone expresses himself as a complete author, capable of ranging between violent gestures and complex aesthetic solutions, elements that find a proper synthesis in the exhibition on display at MIC entitled The Necessary Angel.

Why was the title The Necessary Angelchosen ? What links can be drawn between the words of Wallace Stevens and Cerone’s works?

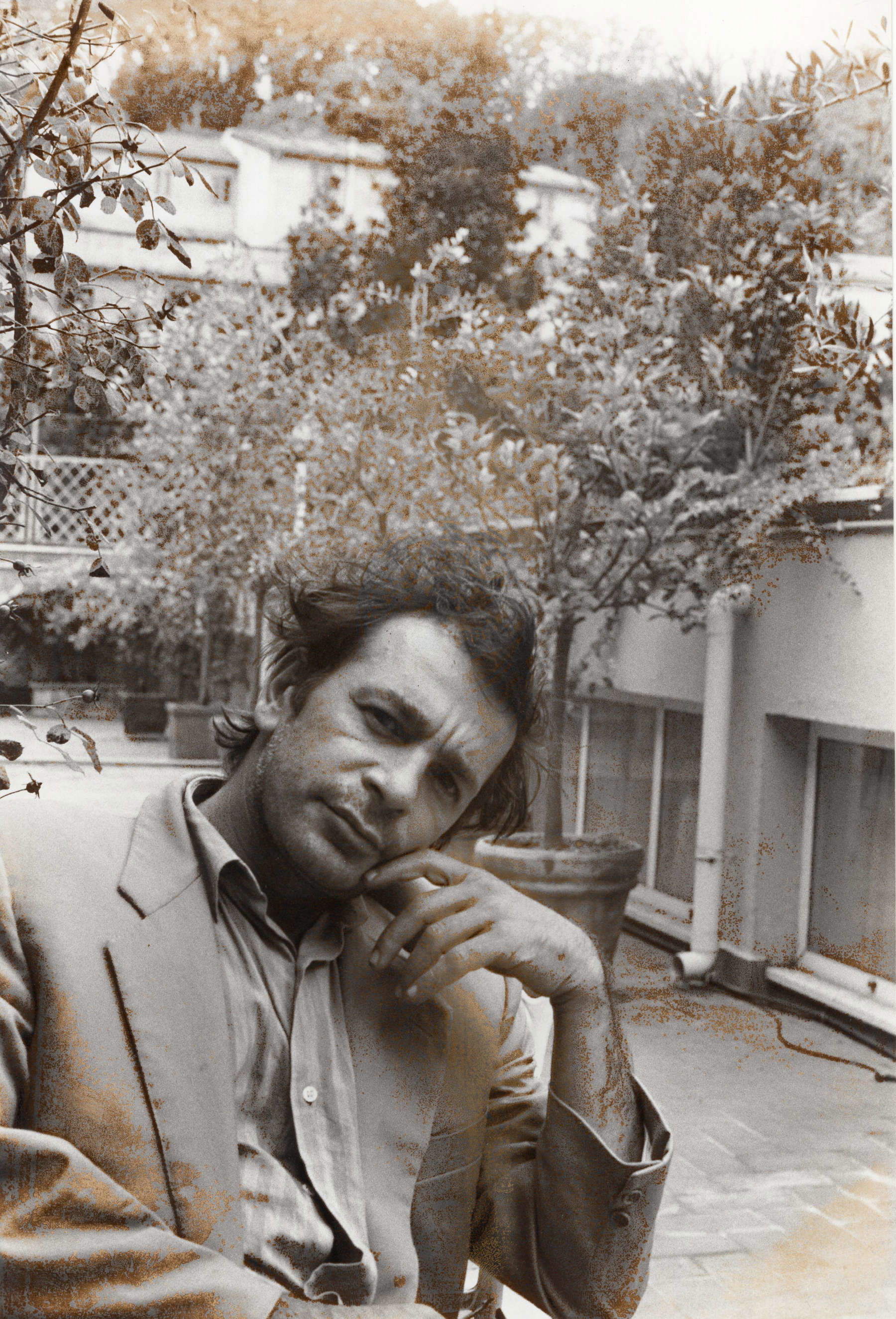

I have always perceived Cerone as a solitary and independent figure in the field of Italian sculpture, capable of maintaining a personal path despite the recognition of critics and gallery owners, and the Roman context in which he lived. His work and his life move with a lightness that carries with it the weight of a profound drama. If we look at his works, the sense of autonomy and originality stands out strongly, and many of his works evoke a sacred dimension: figures of saints, apparitions, ghosts and funerary monuments. These are elements that refer to a mortuary imagery, but not as a commemoration of the end, but rather as an aspiration toward an extreme, a passage to another dimension. Despite being an atheist, Cerone had an absolute faith in sculpture. For him, sculpture and life were inseparable, two sides of the same reality. This is the context for the title of the exhibition, The Necessary Angel, which takes its inspiration from Wallace Stevens’ poem of the same name. In this context, the angel is not a celestial figure, but an earthly entity, traversing the world with its frailties, sufferings and uncertainties. A figure that reflects, in part, Cerone himself: an artist who experienced sculpture as a poetic expression and a means of exploring the indefinite. Although Stevens was not a direct reference, Cerone was profoundly influenced by poetry, especially that of Hölderlin, Dino Campana and Sandro Penna, as well as by personal closeness with Patrizia Cavalli. Cerone’s sculptures are evocative and elusive: figures that are glimpsed without ever being fully defined. There are no recognizable faces, hands or limbs, but only fragments that suggest a presence, as happens in Stevens’ angel, glimpsed and never fully revealed. The tension toward the indefinable and the poetic characterizes the entire oeuvre of Cerone, who has been able to transform matter into a means to explore what is beyond the visible and always remains suspended between concreteness and abstraction.

What themes does the MIC exhibition investigate?

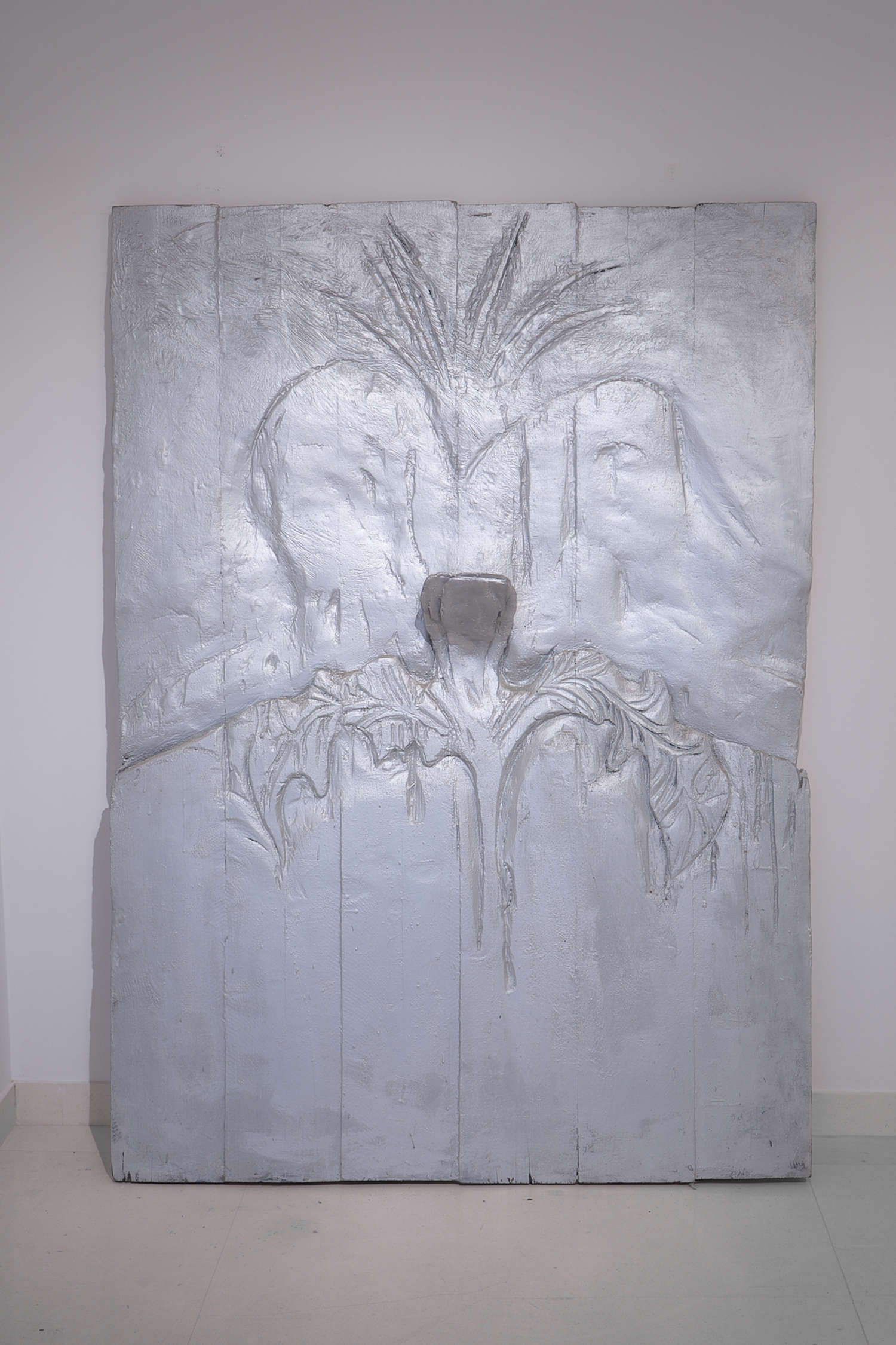

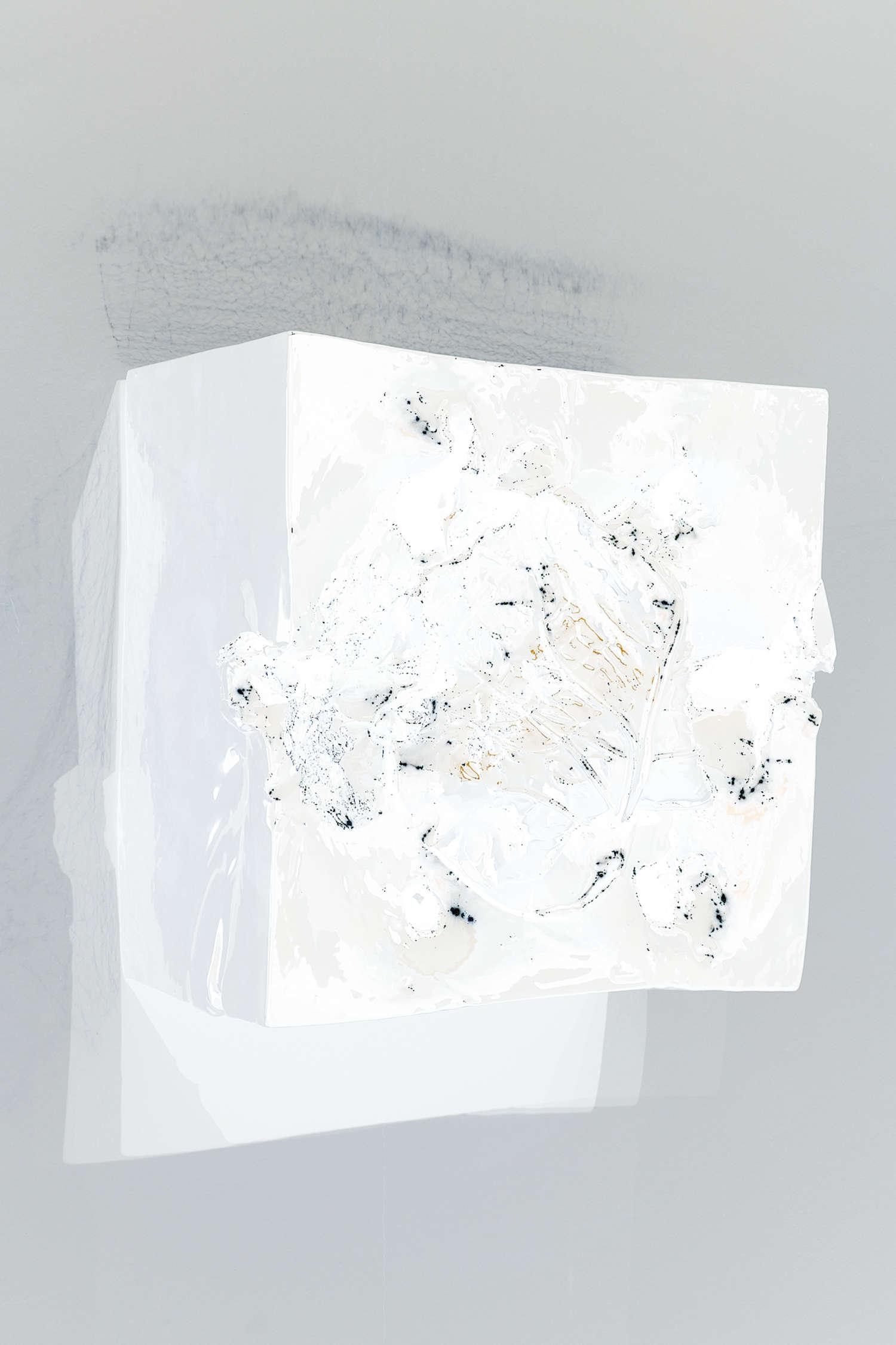

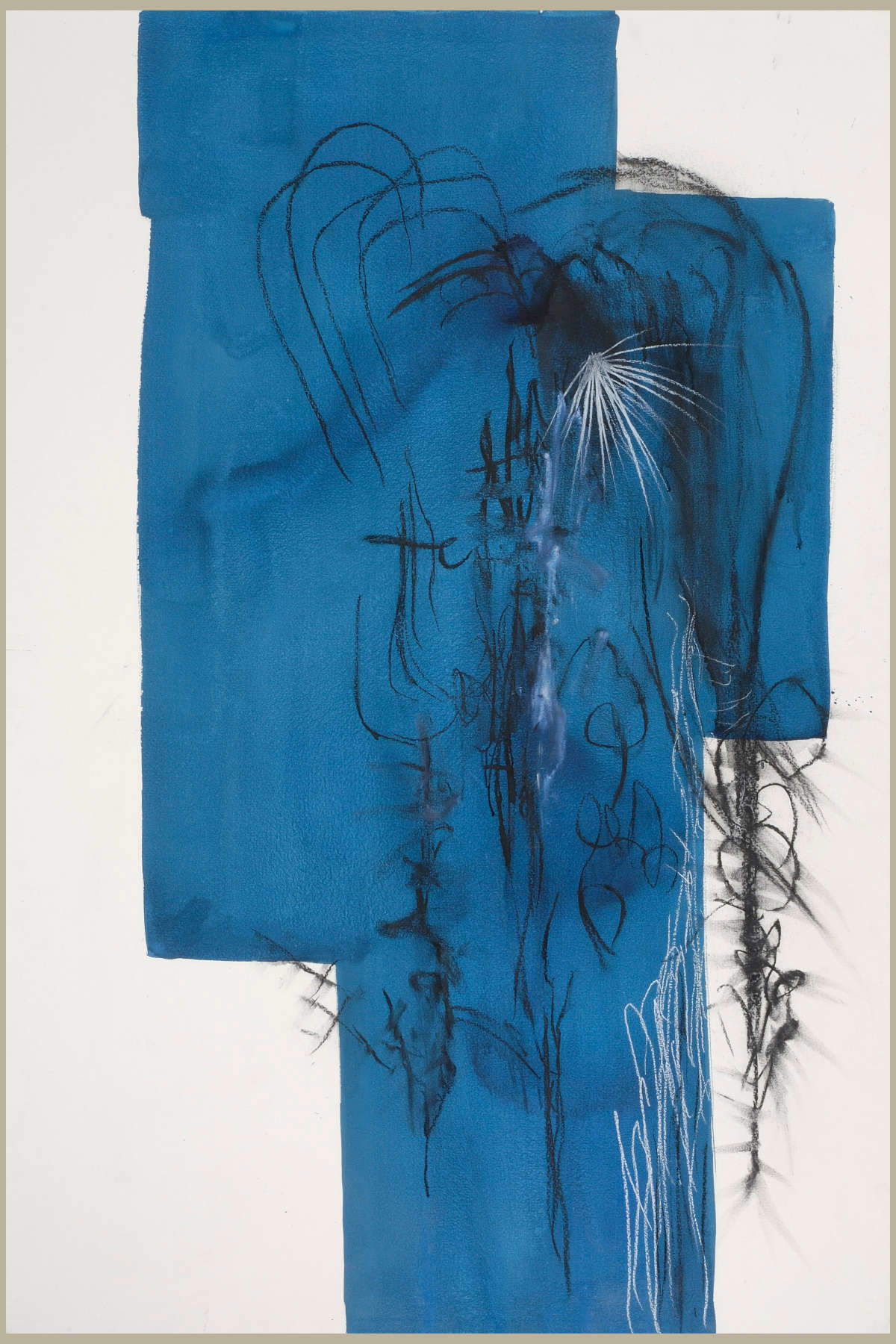

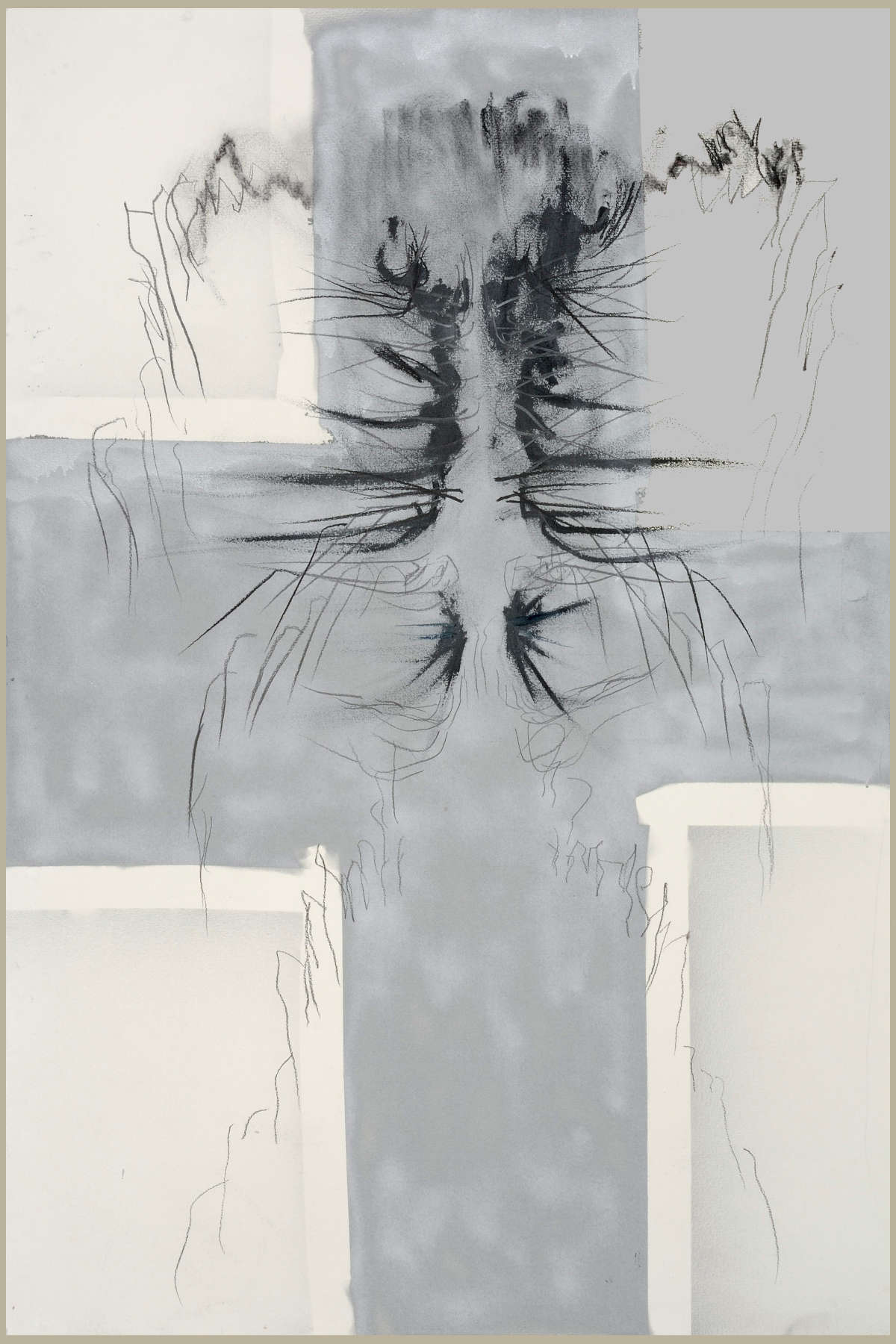

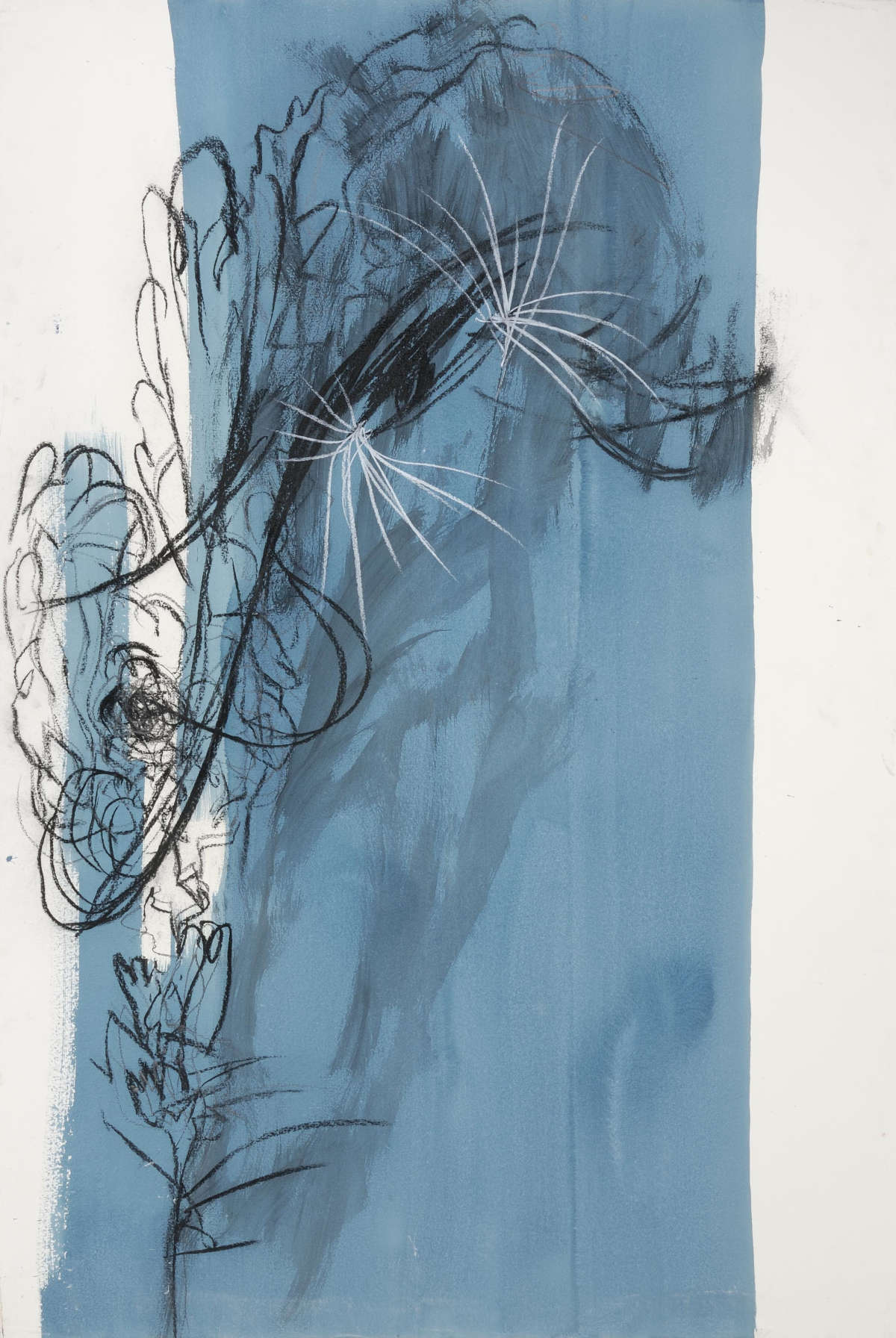

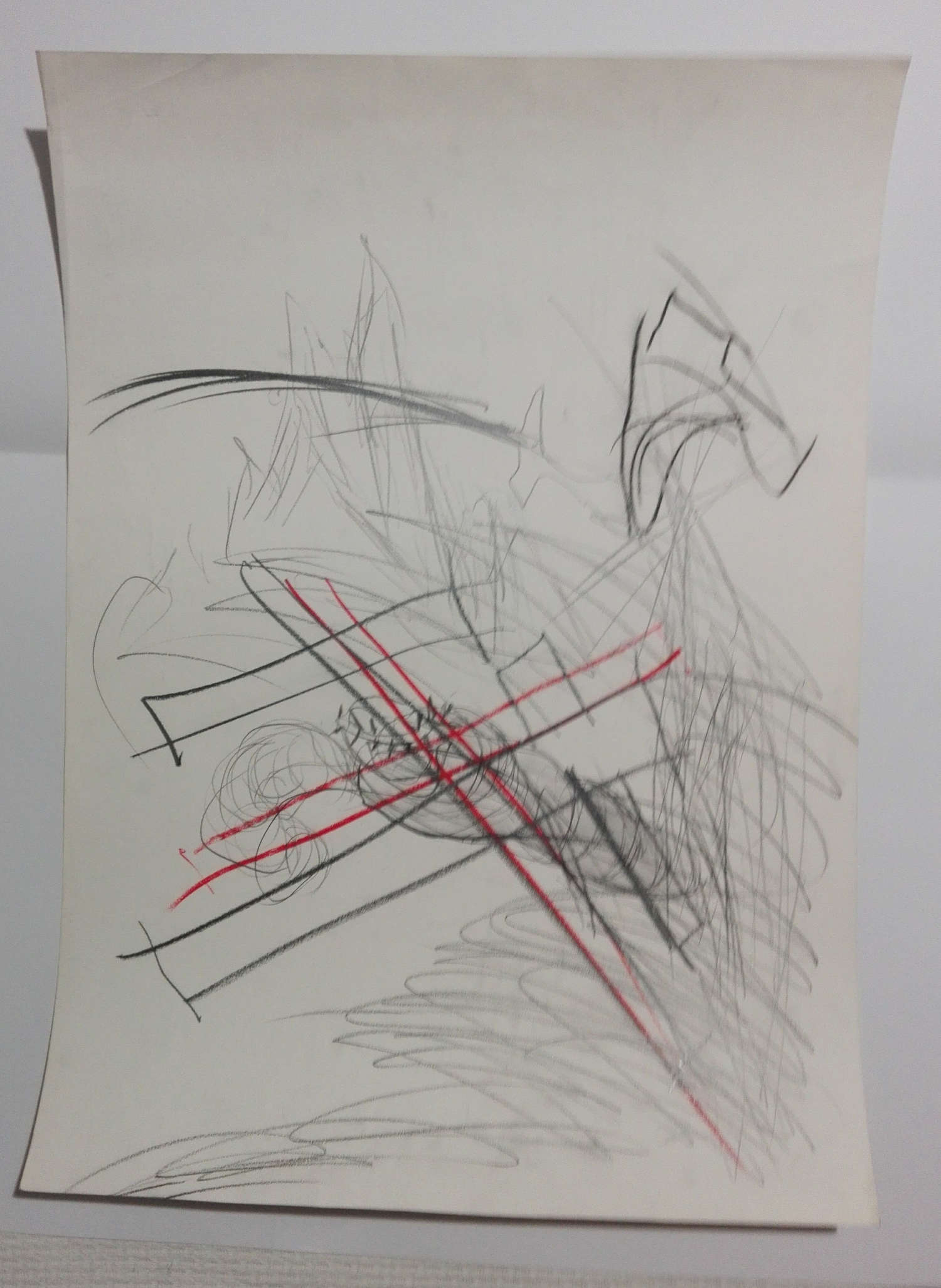

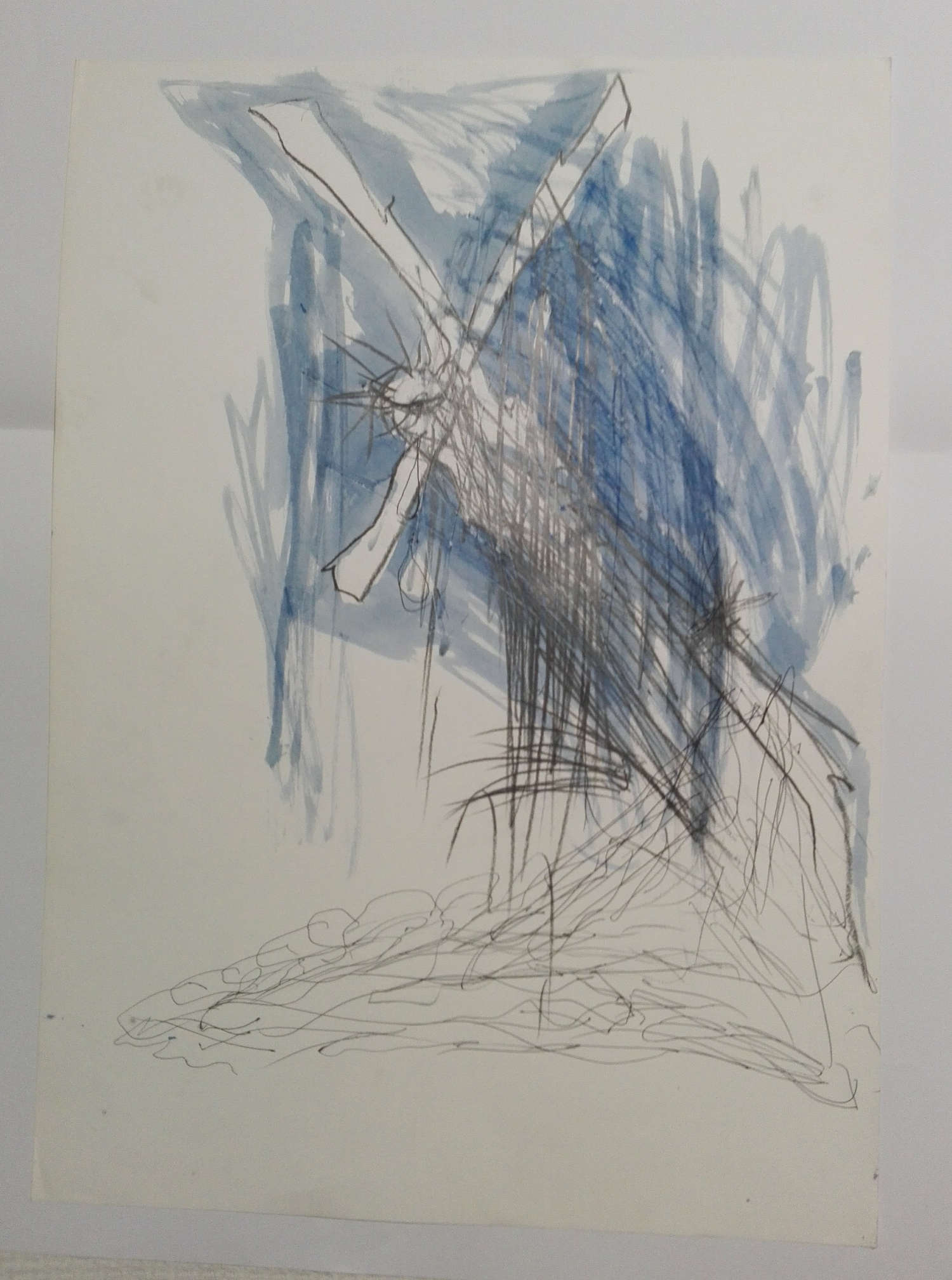

A crucial element of the exhibition is the theme of materials, which embraces much of the repertoire explored by Cerone. Wood, plaster, plastics, glazed and metallized ceramics are present, while marble and stone, although occasionally treated by him (with no more than five works), are absent due to logistical issues related to the difficulty of transportation. Alongside the sculptures, there is a significant nucleus of about thirty drawings that completes the exhibition and testifies to another essential aspect of his artistic practice. The drawings in question, made with different techniques, should be understood as true sculptures on paper. The gesture that generates them has a formal and expressive impact similar to that which Cerone imprints in his three-dimensional works. Among the recurring themes, that of ceramics stands out, with particular attention to the works made in Faenza. Here the link with death stands out through a whiteness that recalls the solemnity and nobility of a statuesque death. The dialogue between the material and the concept of the end expresses a tension toward the extreme, an aspect that resonates in much of his production. Finally, the very theme of sculpture imposes itself at the center of the exhibition. All the works on display take the form of real sculptures, conceived for a museum of ceramic sculpture rather than one dedicated to ceramics.

Cerone is known for his impetuousness and creative freedom. Did these characteristics influence the concept and exhibition design? In what way?

The exhibition space of the MIC - Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche - presents itself as a very peculiar environment, capable of significantly influencing the setting up of an exhibition. For this exhibition, I built the itinerary with the space itself in mind, adapting to its characteristics without conceiving an exhibition that is abstract or unrelated to the place. In Giacinto Cerone’s case, this mode was particularly natural because of the possibility of organizing the works into well-defined thematic groups: the Weeds, the plaster casts, the metallized ceramics, the Vietnamese Rivers, and the four figures of heroines, ancient and modern. The nuclei, already present in Cerone’s work, present a starting point for arranging the works in space organically. The first necessity was to identify and select the groups, taking into account that some were naturally extensible, while others were configured as defined units. Next, I assigned each group the most suitable place within the space, following the physical and visual coordinates of the MIC. The priority was then to enhance the thematic series by emphasizing the families of sculptures conceived by the artist and distributing them in a balanced way to create a continuous dialogue between the works and the space. To further enrich the installation, we decided to take advantage of some seemingly secondary walls to install drawings, both small and large. All of this allowed us to establish a relationship between Cerone’s two main techniques, sculpture and painting.

In your opinion, what is Cerone’s most significant work in the exhibition, especially for a thorough understanding of the artist’s art?

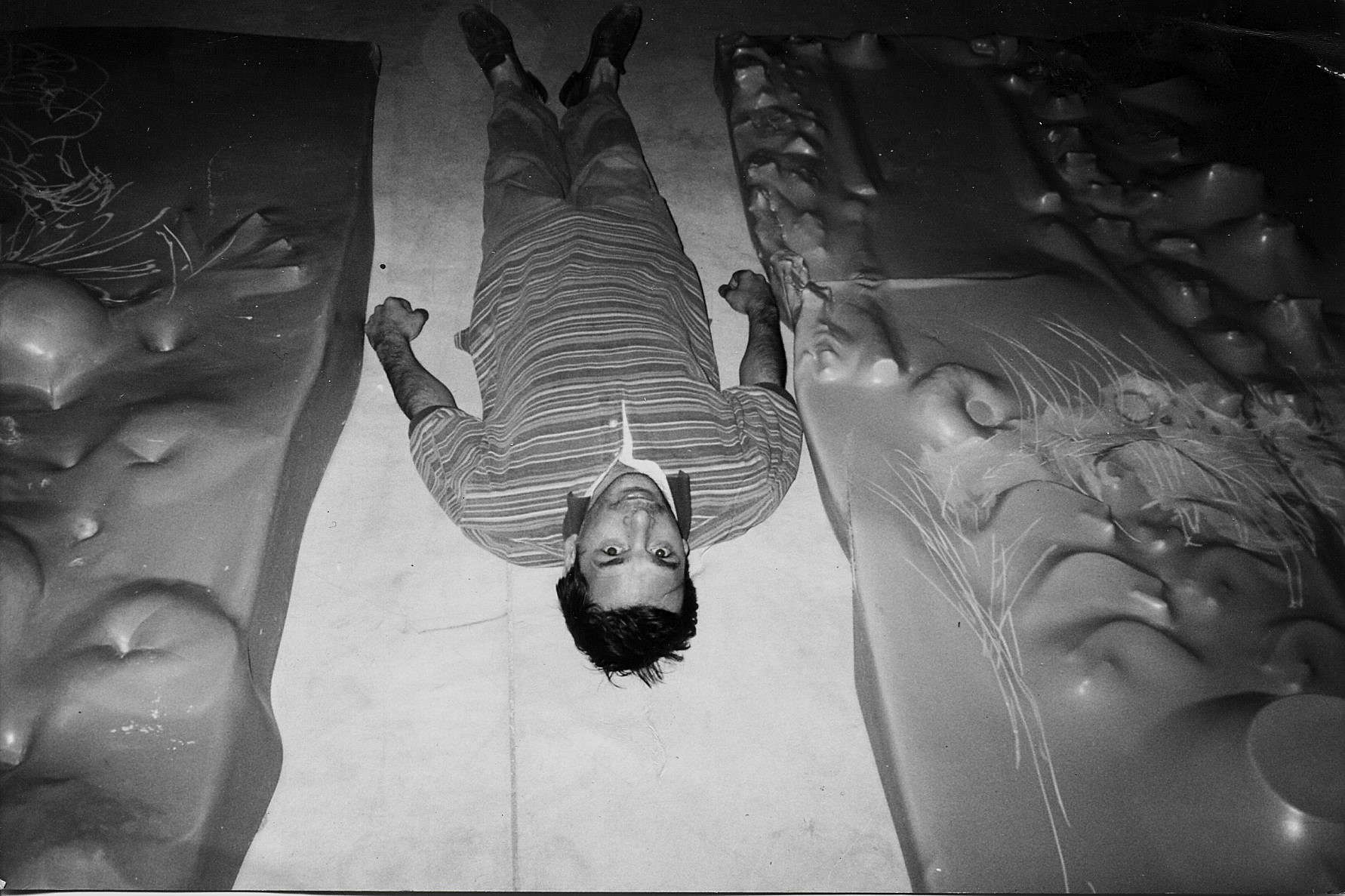

I would propose two solutions for the exhibition that reflect both Cerone’s character and that of the exhibition itself. On the one hand, one of the most powerful and solitary sculptures, Ophelis, deserved to be exhibited in a dedicated room. The work, made in 2004, is among Cerone’s last and carries with it an interesting meaning. It is a white ceramic that pays homage to Ilaria del Carretto or the Veiled Christ of San Martino, but also a self-portrait of the artist, who represents himself through the figure of Ophelia lying down, as if she were dying in the course of her drowning, immersed in water. It is a work that marks a transition from the lived to the imagined, in which Cerone pays homage to the sculpture and, at the same time, to her impending death. To emphasize the sense of solitude and reflection, the sculpture is accompanied by a photographic portrait of Cerone, lying between two other sculptures, as if he himself were the figure of Ophelia. The installation certainly evokes a poignant but also fascinating atmosphere. On the other hand, the series Vietnamese Rivers presents a completely different proposal: six sculptures, four of which are on display in the exhibition, accompanied by ten drawings that analyze the same theme. Compared to the solitary Ophelia, there is a strong cohesion here, a group consisting of sculptures and works on paper.

How does the idea of “total sculpture” materialize in Cerone’s installations, and what impact might it have or elicit in the public visiting the exhibition?

The relationship between Cerone and total sculpture is a concept well highlighted in the exhibition. His admiration for Pino Pascali can be seen in the works he dedicated to him, such as the large plaster floor that was made in Turin and that, despite its damage, continues to speak of the relationship between sculpture and space, symbolically and physically. The reference to Pascali is strong and constant, a link that can also be seen in works such as the white plaster castings that recall the softness and fragility of Pascali’s sea with lightning, and in the horizontal sculptures that evoke an idea of sculpture as a portal or total encumbrance, something that transcends the single piece to become an environmental intervention. Cerone, in fact, pushes the concept of sculpture beyond traditional limits. His sculptures are columns resting on the ground, woods tilted against the wall, horizontal carpets, sculptures that become part of the wall as if they were relief paintings. Each piece seems to seek a connection with the space, with the floor, with the wall, in a continuous interplay between form and environment. The concept of sculpture as a space that expands, as a modular entity that unfolds in the environment, is also exemplified by his Last Supper, a work composed of five parts, which suggests the possibility of a modular sculpture. At MIC, spaces do not allow for the recreation of works that no longer exist. But imagining a large-scale environmental intervention like the one Cerone made at Tor Bella Monaca or elsewhere, a vision emerges in which the sculpture occupies dozens of meters and intentionally dialogues with its surroundings.

Since 1993, the collaboration with the Gatti workshop marked a turning point for Cerone. What unconventional techniques did he adopt, and how did these enrich his poetics?

Cerone’s approach to ceramics is revolutionary. His way of working the material becomes a real act of struggle with the material, and this combat with clay, which Cerone faces with a physical and mental strength comparable to that of a street fighter, is an aspect that distinguishes his art from that of other contemporary sculptors, such as Fontana for example. Cerone attacks ceramics literally. His way of breaking it, tearing it, piercing it with his hands or feet, seemed a direct attack on the material itself, as if he wanted to question its resistance and ability to withstand human intervention. The invention of the process of emptying the clay block allowed Cerone to push the traditional limits of sculpture. He was able to shape structures that could be torn and manipulated without compromising their stability. The fact that the ceramic, once emptied, became a kind of shell that could be bent and perforated, is an innovation that allows the artist to work in a more physical and direct way, entering inside the material without the risk of destroying it completely.

In your opinion, what is the symbolic value of the diversity of materials used by the artist?

I don’t know if there is a symbolic value; he certainly seemed to have a very pragmatic and functional view of materials. For him, the important thing was not so much the material itself, but how it could serve to realize his sculptural vision. The materials were tools that had to adapt to his creative gesture, which changed according to the type of work to be made; I don’t think he loaded them with a predefined symbolic meaning. White, in fact, can be called the exception. In his works it seems to evoke concepts of life, death and sanctity. The choice of white for many of his sculptures dedicated to saints, for example, could be read as a reference to purity, to the transition between life and death, or even to the concept of transcendence. It is as if Cerone saw white as the color that best suited the idea of transformation and transition, both spiritual and physical. Beyond this reflection on white, Cerone never tied himself to a specific material or technique in a dogmatic way. His consistency lay in the gesture, in the idea of sculpture as a physical expression of his vision. Even when he used materials such as plastic or marble, the approach was always dictated by the need to identify with that material, in order to adapt its strength and technique according to its yield and possibility.

Twenty years after his death, what trace has Cerone left in Italian contemporary art? How do you think he is perceived today by new generations of artists?

The answer is not simple. Although Cerone had a considerable impact in the artistic sphere, his recognition is still not as consolidated as that of other artists on the contemporary scene, and this depends in part, on the fact that he did not have a stable market or a constant following from critics and curators. Despite the fact that his work is appreciated and the galleries that promote it support him, he has not been able to establish an established historical presence as happens to many other artists, especially those more linked to recognized movements. This condition seems to be related in part to his choice to remain outside the more traditional circuits of art history, not aligning himself with groups or critical theories that influenced the Italian art scene of his time. His career was essentially independent, which made him a special case compared to the traditional dynamics of art history. This has certainly limited the knowledge of his art among new generations, who, with rare exceptions, do not seem to have a full awareness of his impact. The generations that worked with him, such as his assistants in Rome, are now adults, and so all that remains is to hope that art history and critics will be able to give Cerone the place he deserves, recognizing his value and the scope of his creativity in the field of Italian sculpture.

Could the museum have future projects related to Cerone or related themes planned?

The process of planning exhibitions is often a work in progress, and there are so many dynamics that need to be made official before any future programs are announced. I don’t know about MIC’s future programs apart from the upcoming Faenza Prize in June dedicated to international sculpture, but what emerges, however, is that the museum has started an important valorization of Cerone with works already in the permanent collection, and the current exhibition, accompanied by a catalog published by Corraini with an introductory text by the museum’s director, Claudia Casali, is definitely presenting a new look at his artistic production. Certainly, the publication of a well-edited catalog, which analyzes the artist’s poetics in depth, is always an excellent tool to enrich the critical landscape and to raise awareness of the value of his work among a wider audience as well.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.