Futurism is an avant-garde that is still relevant, revolutionary and free. Simona Bartolena Speaks

The Futuristsexhibition opened at the Palazzo delle Paure in Lecco on March 18 .A Generation in the Avant-Garde, running until June 18, 2023, where works by the movement’s leading exponents will be on display. We asked curator Simona Bartolena to tell us about what sparked the idea for this exhibition, what aspects she wanted to focus on, the most important works on display, the arrangements, and more. The interview is by Ilaria Baratta.

IB: How did the idea for this exhibition come about?

SB: The exhibition is part of a larger project: a journey through Italian art between the 19th and 20th centuries that the Lecco Museums undertook years ago with Vidi Cultural and with yours truly as curator. After a series of exhibitions dedicated to nineteenth-century art in Italy, we arrived at this exhibition, which is the first in a series of four dedicated to the first half of the twentieth century. The next ones will be devoted to the Return to Order (June-November 2023), the post-World War II period (March-June 2024) and the 1960s (June-November 2024).

She said that although in recent years the leading role of Futurism in the European context has been widely recognized even internationally, even today the general public’s knowledge of it is not complete and thorough, as most texts devoted to this Avant-Garde focus on the early years of the movement. So what is the public “missing” in the full knowledge of Futurism? Why is it that for a proper reading of Futurism one cannot ignore the analysis of the following two decades as well?

Undoubtedly the 1910s marked the most experimental and important moment of the movement founded by Marinetti in 1909, but it is wrong to think that Futurism died out in the following decades. In the Twenties and Thirties, on the contrary, Futurism experienced an extraordinary diffusion, spreading throughout the entire peninsula (even in provincial areas and no longer only in large cities such as Milan and Rome), with a series of linguistic variables and different interpretations that make it a truly unique phenomenon in the panorama of historical avant-gardes. It is in its second phase that some of its peculiar characteristics are defined, such as its interest in the applied arts and its engagement in the most diverse disciplines (from theater to dance, from advertising to fashion...). The 1920s and 1930s also saw the emergence of particular trends within the group - such as Aerofuturism - which gathered numerous adherents from the most diverse areas of the peninsula. Aerofuturism, in its various expressions, is an inescapable aspect of Marinetti’s movement: not analyzing it means not having a complete vision of Futurism.

What are the goals of the exhibition, besides telling in general about Marinetti’s movement?

The Lecco exhibitions are created with the intention of exploring an art-historical period in a very narrative and didactic way. Therefore, the goal of the exhibition is first and foremost to narrate Futurism even to a lay audience. In particular, the exhibition aims to clarify some often neglected issues, such as its relationship with the European cultural scene and the presence of an Italian abstract trend. The project’s exhibitions also seek to tell through the works on display the historical moment under consideration, with insights into the society, taste, economy, politics and culture of the period.

Who does the exhibition intend to address? A diverse audience, or is it designed primarily for an audience of connoisseurs of the movement?

The exhibition is designed both for insiders and connoisseurs of the movement (who will appreciate some little-known works and the presence, in addition to the great protagonists, of less familiar artists) and for the less experienced, who will find explanatory panels and commented captions for almost every work on display to support their visit. That of wanting to narrate the works with explanatory captions and of wanting to equip the exhibition with a good apparatus of narrative panels is a personal choice of mine that I cherish. The path of an exhibition must be motivated and narrated. It is not enough to hang interesting works on the walls: a visit to a temporary exhibition has to tell something, it has to offer the visitor a reason for reflection and the discovery or exploration of a theme. The exhibition I think is also suitable for schools. Futurism is an avant-garde that is still very relevant, as well as revolutionary, free, colorful and unprejudiced just enough to attract even the youngest visitors.

Does the exhibition also intend to bring out new aspects of the movement?

Yes. Indeed: that is its main purpose. In Milan we have an extraordinary museum, the Museo del Novecento, which has the most important collection of Futurist works in the world. It would make little sense to organize an exhibition that insists on the same themes and on a period so well represented in the halls of the Milanese museum. For this reason, too, I decided to focus on some lesser-known and addressed themes, such as, for example, the relationship (of “love and hate”) with Cubism and the presence of an abstract tendency in the ranks of the movement, represented above all by Giacomo Balla. In this regard, I wanted to devote a special reflection to the involvement of the Como group of Abstractionists in Futurism. With the invaluable help of Luigi Cavadini, I also recounted this well-discussed aspect, bringing to the exhibition three works by Rho, Radice and Badiali chosen from those they exhibited with Marinetti.

Futurism was not only an artistic movement, but was also open to dialogue with other forms of expression, such as cinema, literature, music, theater, fashion, advertising, and design. How is this aspect investigated in the exhibition?

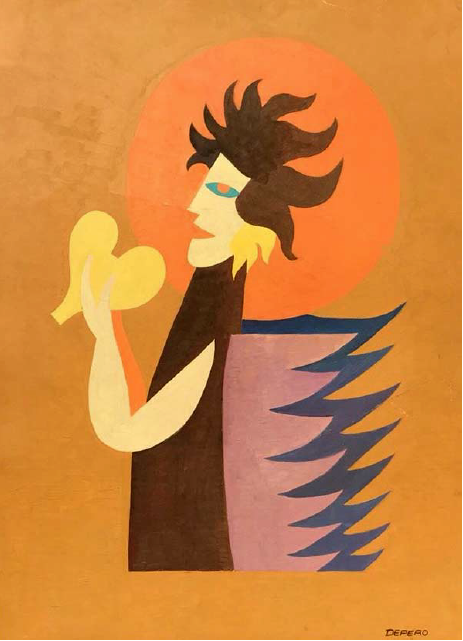

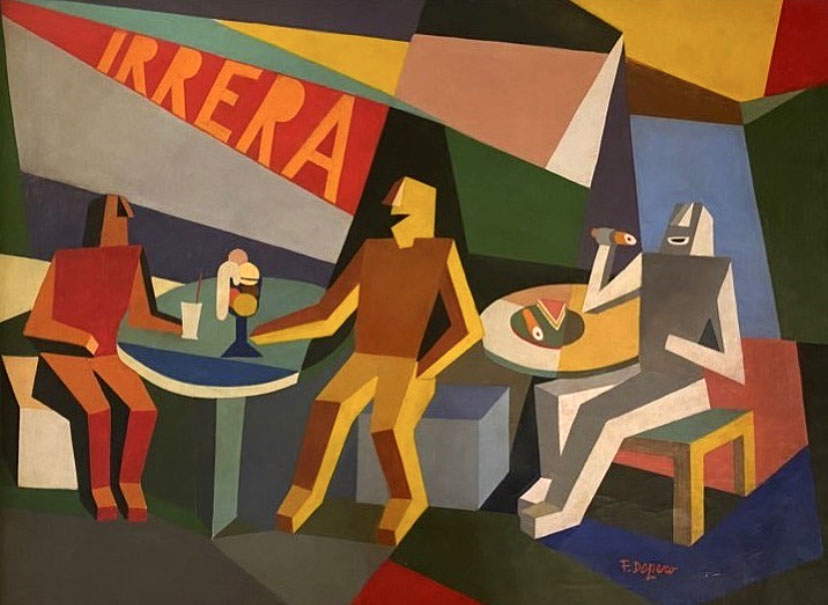

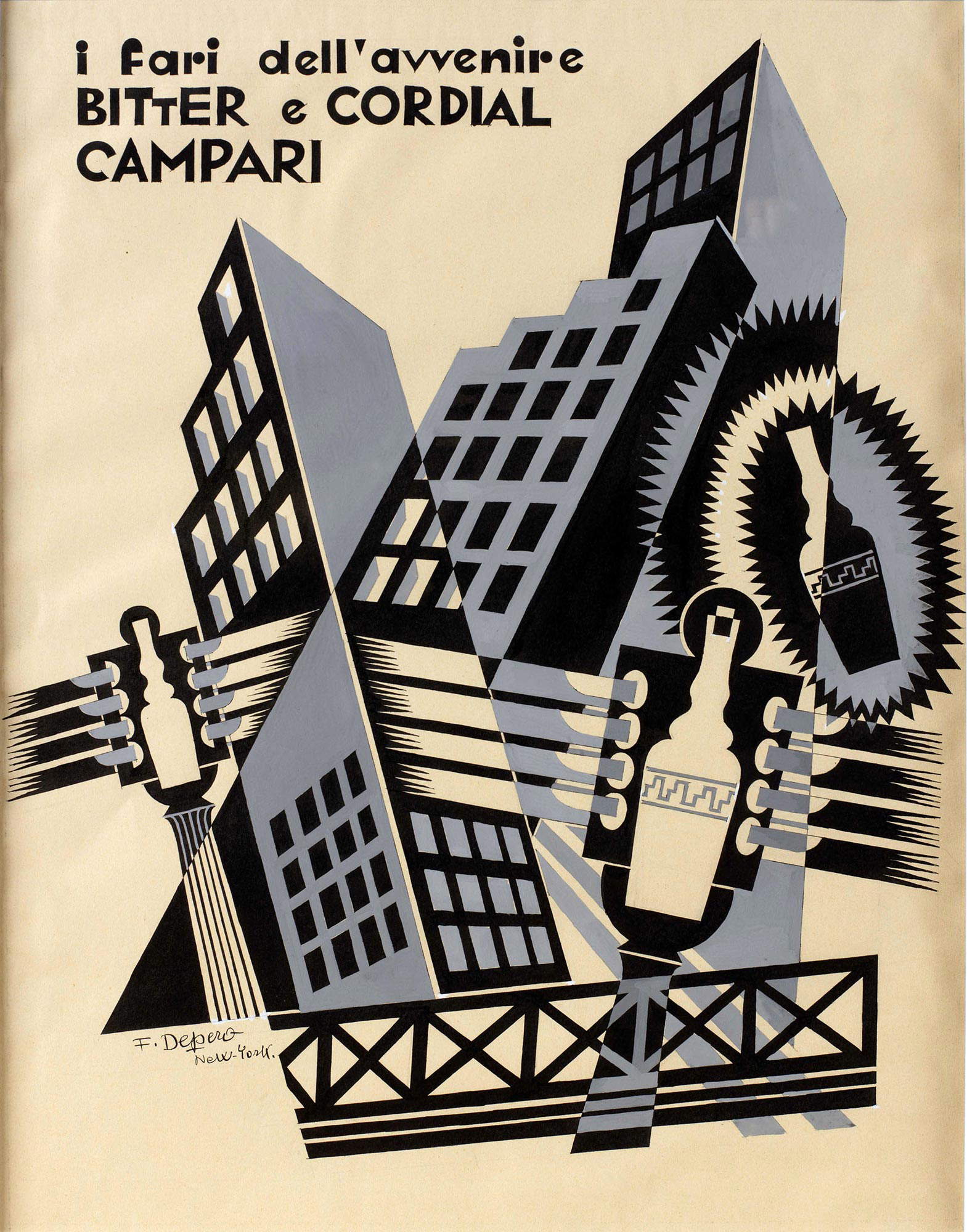

Yes. This is a fundamental aspect. We have devoted a lot of space in the exhibition to this extraordinary fertility of Futurism in different disciplines. Indeed, on display are posters and studies of puppets for the theater, sketches for the decoration of fabrics and tiles, a ceramic plate from Albisola, books, an extraordinary autographed menu of a well-known Futurist dinner, Depero’s advertisements for Campari (including his visionary puppets), Russolo’s Intonarumori (the father of noise music and forerunner of electronic music), Tato and Bragaglia’s experimental photos, and much more.

How is the exhibition developed? In a chronological sense, by themes...

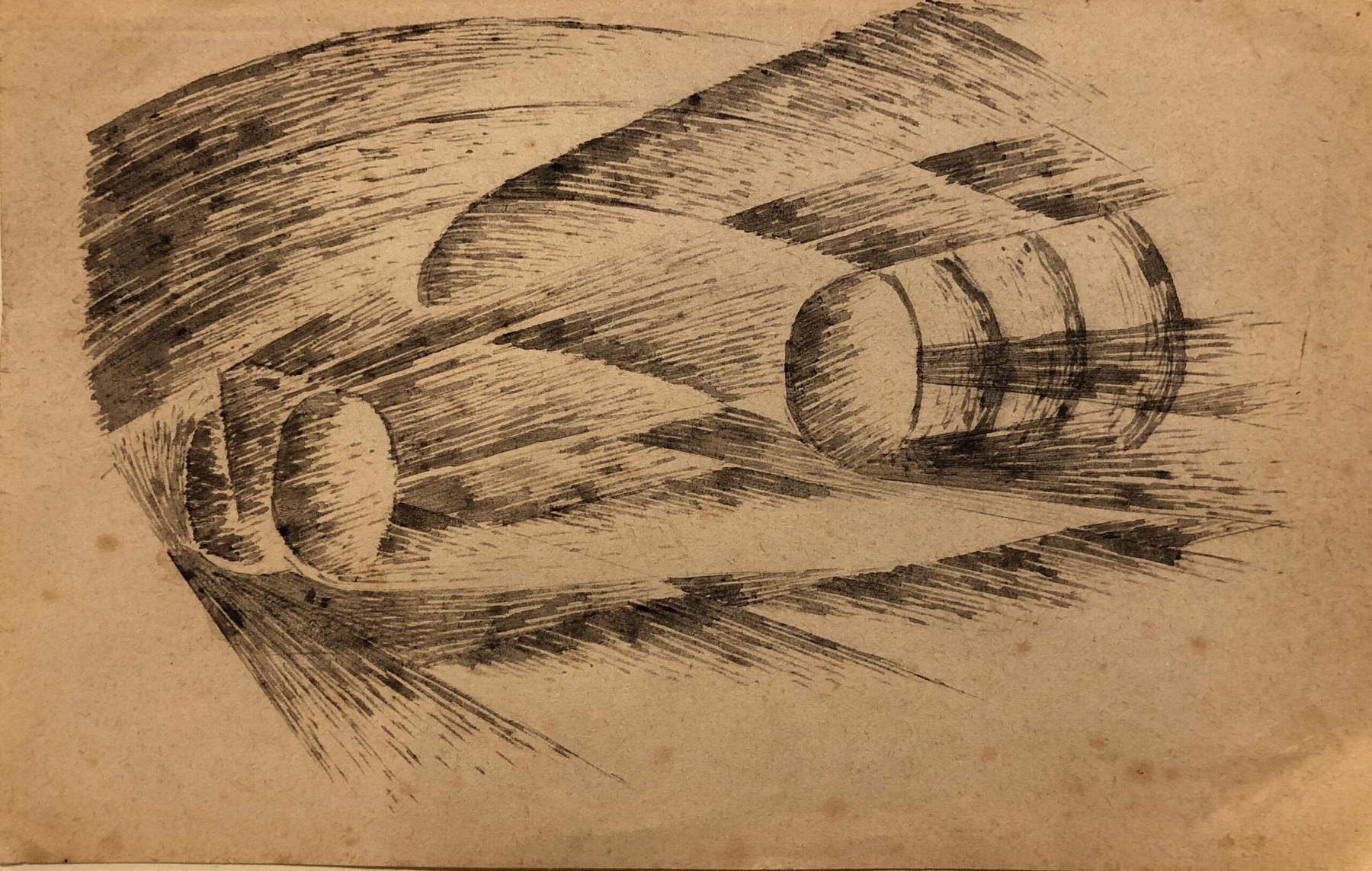

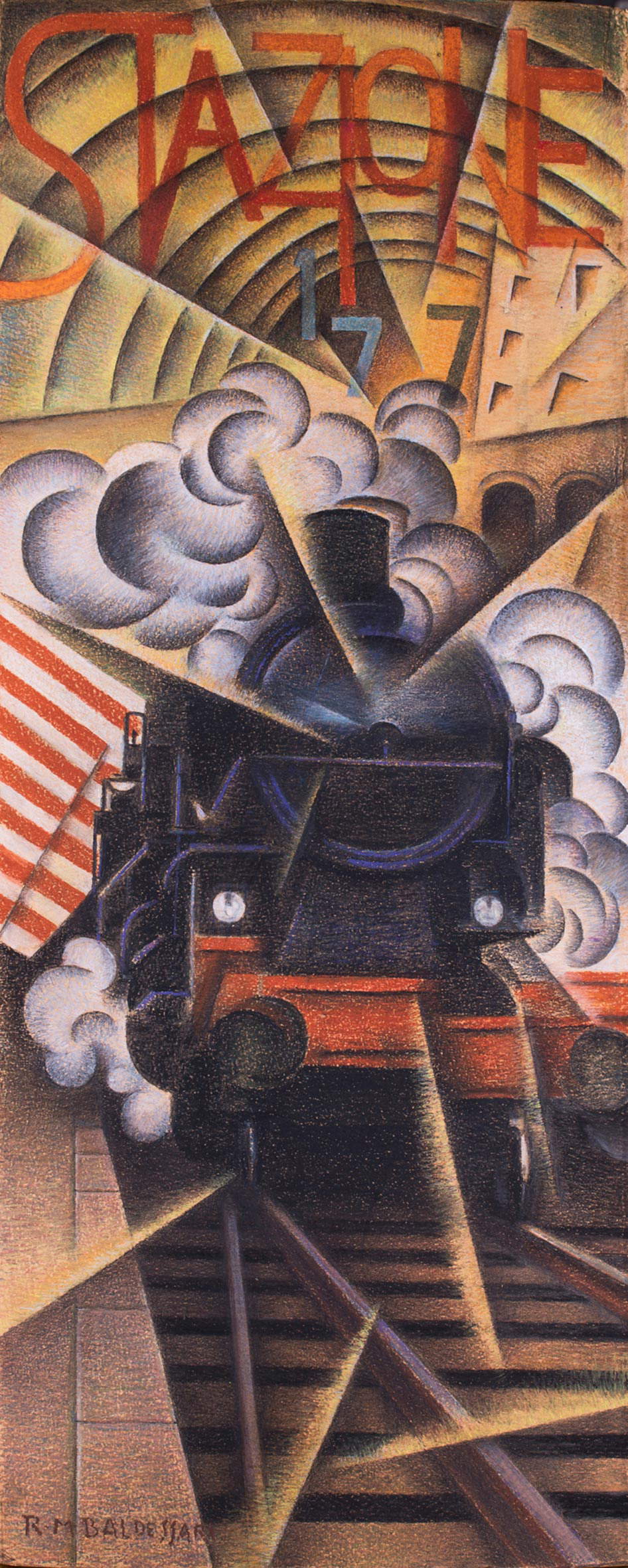

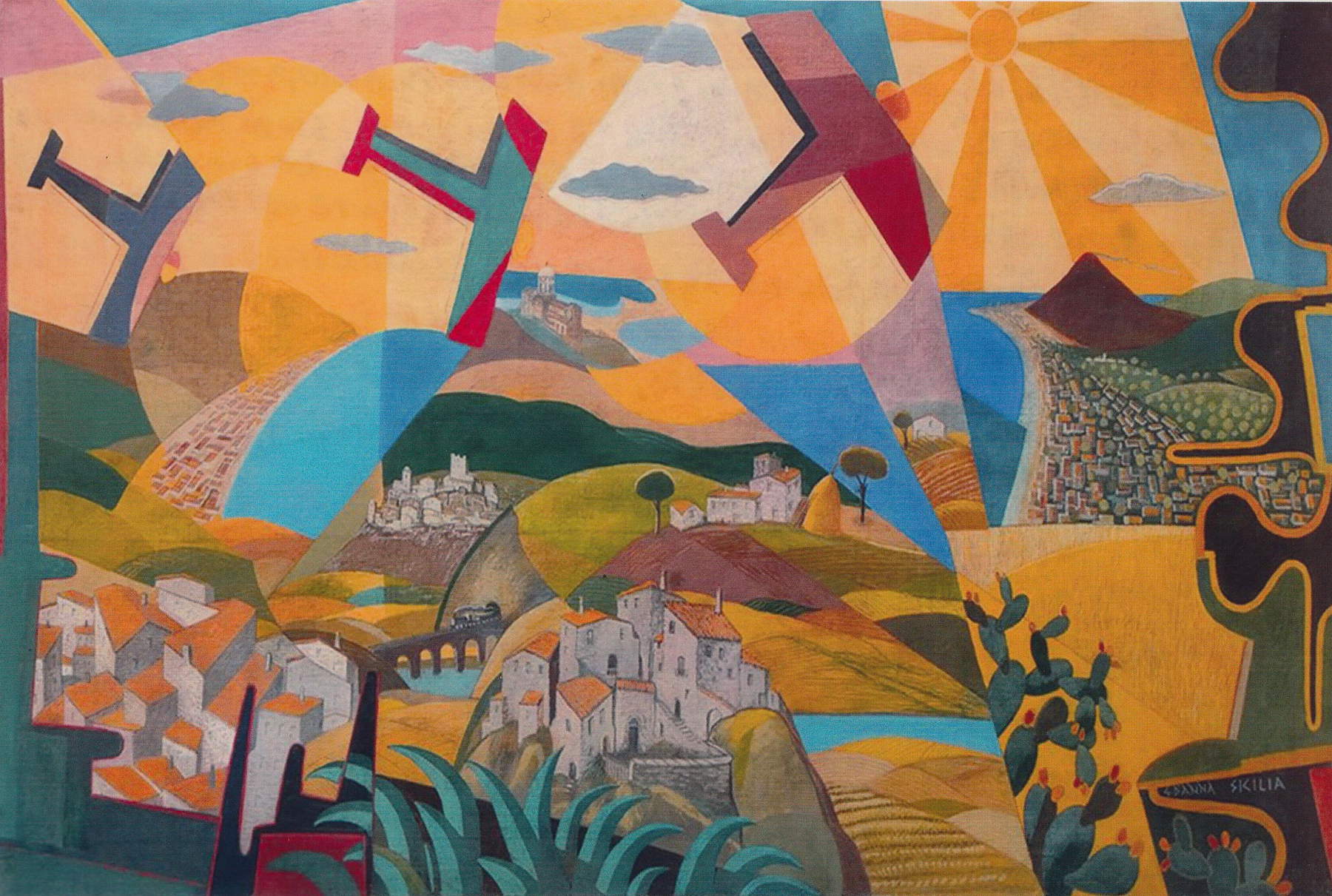

The path begins with an analysis of the movement’s origins, with works by its founders, and the period of the First World War. A large section is then devoted to the relationship with the European avant-gardes, with works by Picasso, Braque, Larionov, Severini, Carrà, Sironi, Baldessari, Sonia Terk Delaunay and others placed in dialogue. It then continues with an in-depth look at abstractionism and its presence especially (but not only) in the work of Balla. We then move on to an analysis of one of the movement’s founding themes: dynamism. After trains, racing cars and whizzing motorcycles, we enter a colorful and highly varied section, the one devoted to the Reconstruction of the Futurist Universe theorized by Balla and Depero, which encompasses the activity of the Futurists in a wide variety of disciplines. A special focus is devoted to the art of advertising, with the presence of various masterpieces by Depero. Finally, we enter the last section, perhaps the most surprising and unexpected, which is dedicated to Aerofuturism and Cosmic Futurism. This section exhibits works by even lesser-known artists, such as D’Anna, Bruschetti, Barbara, and Thayaht, as well as the better-known Crali, Dottori, Prampolini, and Fillia. Speaking of Barbara, I would like to emphasize the role of Futurist women, who are also represented in the exhibition by a poster designed by Benedetta Cappa and a masterpiece by Regina. The exhibition closes with a niche dedicated to Como abstractionists and their relationship with Futurism.

What are the core works of the exhibition, the most important ones?

The exhibition enjoyed an important (and fundamental) loan from the Wolfsoniana, an extraordinary collection now part of the heritage of Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, and from the Campari Galleries, but the works come mainly from private collections and from the artists’ archives. They are, therefore, often little-seen works and all to be discovered. The exhibition includes works signed by the big names-from Boccioni to Balla, Severini to Russolo-but I prefer to point out those by lesser-known artists: Baldessari’s Treno and La natura morta con Lacerba, d’Anna’s Sicilia aerofuturista, Regina’s Ritratto del nipote, Crali’s Passione tra le nuvole, and Depero’s always tasty paintings-publicity paintings...

Were the displays specially designed to further immerse the visitor in that era?

We chose to paint some of the walls bright red, to enliven the museum’s exhibition spaces. The scanning of the works on the walls also follows untraditional rhythms, indulging in some irregularities not usually imaginable for an art exhibition. Moreover, having to display books, objects and paper documents as well, there are showcases and display cases on display. The most engaging room from this point of view is undoubtedly the one devoted to advertising and music, with Depero’s Campari puppets and two Intonarumori by Russolo in the middle of the room. As I mentioned earlier, the exhibition is equipped with extensive and extensive educational apparatus to make the visit usable for all kinds of audiences.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.