Drawing is bare sculpture. Conversation with Riccardo Gemma

A conversation with Riccardo Gemma (Rome, 1963), a graphic designer and illustrator who talks to us about his art. After art high school he graduated from the IED, as a graphic designer he works freelance, mainly in publishing for contemporary art. He has collaborated with countless artists, galleries, foundations, museums. He still collaborates with the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome and the Maxxi, among others. He has also designed and created the image for contemporary art events and other institutional events. As an artist, he exhibited at Galleria Ugo Ferranti (Rome) in 2008, at the open studio in Via Portonaccio (Rome) in 2009, and participated in the FourteenArtTellaro (Tellaro, La Spezia) exhibitions in 2019 and 2022.

GL: Hi Riccardo, for most artists the first “symptoms” of this serious disease called art manifest themselves in early childhood in most cases unconsciously, sometimes transmitted by more or less close relatives. Did this happen to you as well?

RG. The first thing that needs to be said is that there have always been a lot of books in our house, of all genres, from encyclopedias to art history books, from literature to architecture and design magazines, to comic books, of course. My father was into architecture and furniture, “modern” things let’s say, my mother on the other hand was classically trained, loved symphonic music, old churches and Ingmar Bergman. Of old churches and museums we visited many as children, on trips with our parents, however, of things to look at and absorb there were many in the house. I would spend hours flipping through books and “looking at figures,” lots and lots of figures (a constant discovery) and reading comic books like all kids. I think my passion for “figures” came about because of the many books we had, so a passion not really born directly from people. However, I had an uncle and grandfather who painted as a hobby, so I guess I must have inherited something. Especially from the hobby point of view. Speaking of my uncle, I remember a small painting he painted that I really liked as a child. It was a portrait of a gentleman with an intense and stern expression, with a beard and a striped shirt. At that time I did not know who that gentleman was, and this fact of not knowing, this “enigma,” appealed to me. Then many years later, again in books, I found out that that gentleman was Henri Matisse, a copy of the 1906 self-portrait. As a result, I also understood why I liked him so much. In an art history book I discovered Francis Bacon’s Crucifixion, alongside Burri, Moore, Giacometti, Warhol. I was enchanted, I liked them all. They were moments close to happiness. However, I didn’t know and I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand anything. The important point, I think, lies precisely in this “not understanding.” It brings you closer to things in a direct, instinctive, primitive, happy way. You feel like you see even further, something bigger and more extraordinary, which probably doesn’t exist. Is an emotional state, the first hints of spirituality. Not understanding is a promise of revelation, it is Jean Cocteau’s “secular mystery,” it is the first sacred time.

Have you ever had the desire to take hold of these images through drawing by copying them to make them your own?

Yes of course, but more than the desire to take hold of an image by copying it, there was this innate urge to emulate. To this day, when I see something I like (a painting, a sculpture, a video, a movie, a book graphic), I instinctively want to remake something similar, something that lives up to it, but in my own way. Of course it happens very rarely, I have also learned to enjoy things without “performance anxiety,” yet this fibrillation is always there. Except, as a kid, reading a lot of comic books (superheroes mostly) made me want to make them too. But I would not copy them, I would look at them, study them, then close the comic book and start drawing characters of my own “in the manner of.” This is a method that came naturally to me, spontaneously. I think it is a good exercise to metabolize things by making them your own in an original way, trying to draw on your own emotional resources, also, of course, through memory and what inspires you. A technical exercise, but also a spiritual exercise. But then, later on, in my high school days, I also started copying pictures that I liked that I found in magazines. I used to copy them in pencil, as precisely and analytically as I could (I got a bit fixated on the hyperrealists). So I learned chiaroscuro, something I had never learned and understood by copying from life. And that’s where the problem comes in: my limitation in understanding the reality around me. I was learning to understand images, and in the meantime I was escaping the understanding of reality. I was intuiting it, precisely, through images. So I started taking pictures with an SLR (another good training exercise), pictures that I would then repaint in oil. This is also an interesting process of appropriation.

Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo

Riccardo Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo

Riccardo Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo

RiccardoWhat was your educational background? During your studies, did you make encounters with people that turned out to be important for the later development of your work?

I went to art high school and then graduated from IED in the graphic design course. Graphic design would later become my job. With some of my high school classmates I formed a friendship that, more or less, still lasts. I must say that I was lucky, let’s say that my cultural education in a more contemporary sense (but not only), I owe it to them. They were curious and intuitive kids, ahead of me. We talked about everything, about art of course, movies, music, books, new things. I would listen and learn. There was always some new discovery to dissertate and reason about. We talked about artists, people, and girls. I learned a lot, but the most important thing was that with them I developed a certain critical and aesthetic sensibility with respect to art and, in some way, with respect to life. And then, although still very young, they already had quite clear ideas: they would become artists, or writers, who knows. So, in the years after high school, they introduced me to the mysteries of contemporary art and I met many other artists, and critics and gallery owners, and as a result I made new friends in the Roman environment. In the meantime I kept drawing for myself, taking photographs, painting a little bit. Also at IED I met people with whom I shared a passion for graphic design and with whom I also began to work. In any case, my work as a graphic designer then increasingly took place in and for the contemporary art world, where I actually felt more at home, let’s say, being accustomed to the subject by now. And there it comes full circle. Or a circle, I still don’t really know.

Did you ever feel like being an artist yourself during those years?

I was actually quite confused. I knew there were some things I liked to do, so I didn’t mind the idea of being an artist either. I knew that I had a talent for drawing, but at the same time I discovered that I also had a talent for graphic design (in high school we did some graphic design work), so I kind of imagined myself as a painter, I kind of imagined myself as a graphic designer, I kind of imagined myself as a comic book artist, and I kind of imagined myself as a comic actor. I am a lazy and therefore fatalist, so I always thought “whatever, let’s see what happens.” The truth is that talent is not enough, imagining yourself as an artist is not enough, you have to really want it, you need awareness. And anyway, in general, things have to be pursued, it takes determination, you have to persevere, otherwise it means they are not that important. The sooner you understand that, the better. But these are arguments made in hindsight, at the time I didn’t have much of a sense of direction, so to speak.

So you continued to lull yourself into this indecision?

No no, I decided to do the Academy of Fine Arts, painting (perhaps without much conviction, perhaps), but I didn’t pass the entrance exam. However, I was neither disappointed nor disheartened, I regarded it as a “possible episode” in the normal flow of events. I could have tried again the following year, but opted for graphic design. Evidently I did not have the so-called sacred fire of art. At this point I could quote John Lennon’s famous phrase, but I don’t. However, I continued to frequent art friendships, artists’ studios, to see exhibitions. And to draw when I felt like it, in a very free, serene way. Those were also moments close to happiness. In principle, I never stopped again. Senonché, in more recent years, I found myself with an interesting body of work let’s say, which I decided to make public (albeit episodically) thanks to the encouragement of friends. In short, at this age I have learned, generally speaking, that one thing does not exclude the other, things can coexist. All things. It sounds trivial, stupid, but for me it is a small revelation.

Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo

Riccardo Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma,Has your work as an artist always proceeded on its own independent track from your work with graphic design, or have there been times when the two coincided?

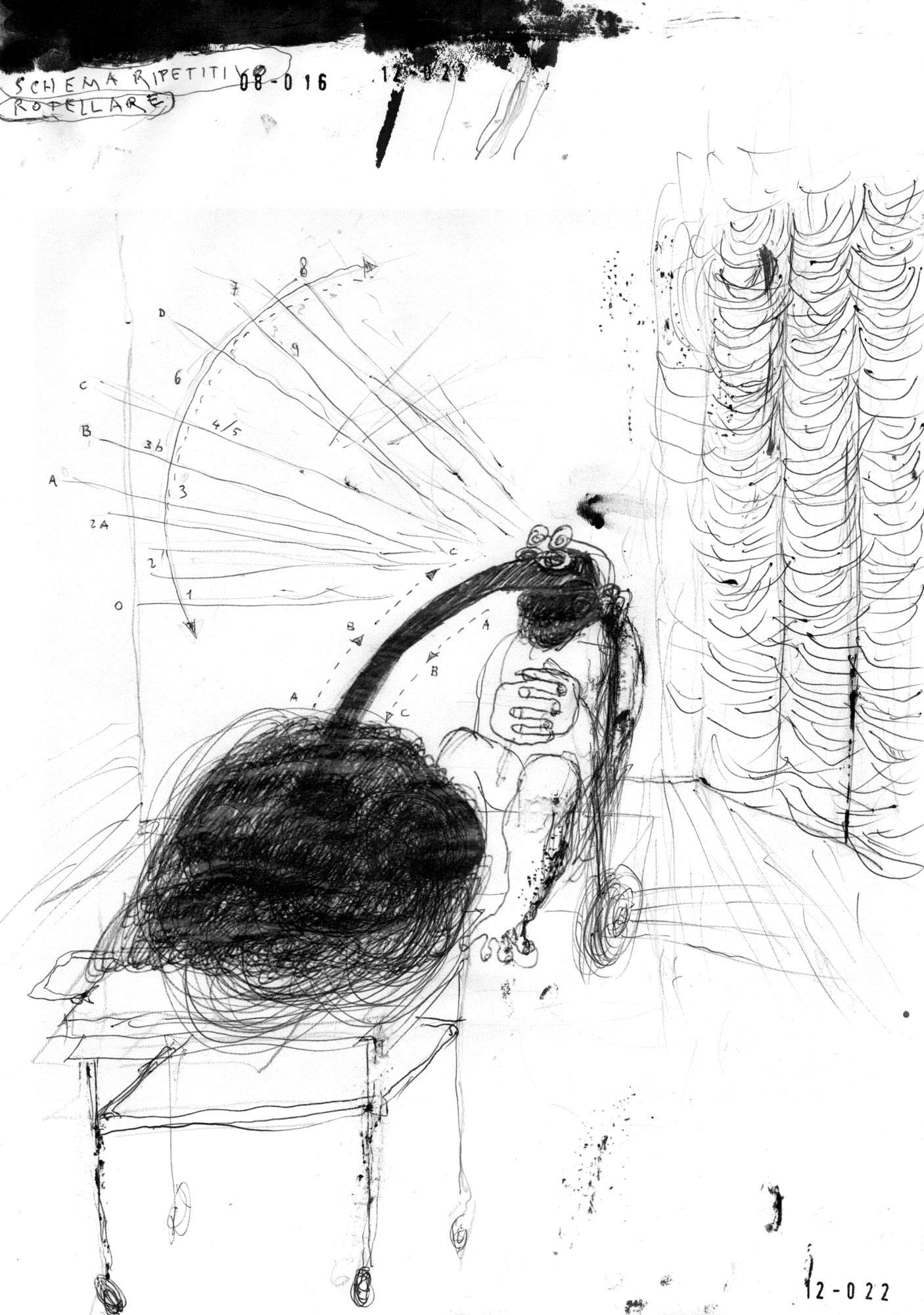

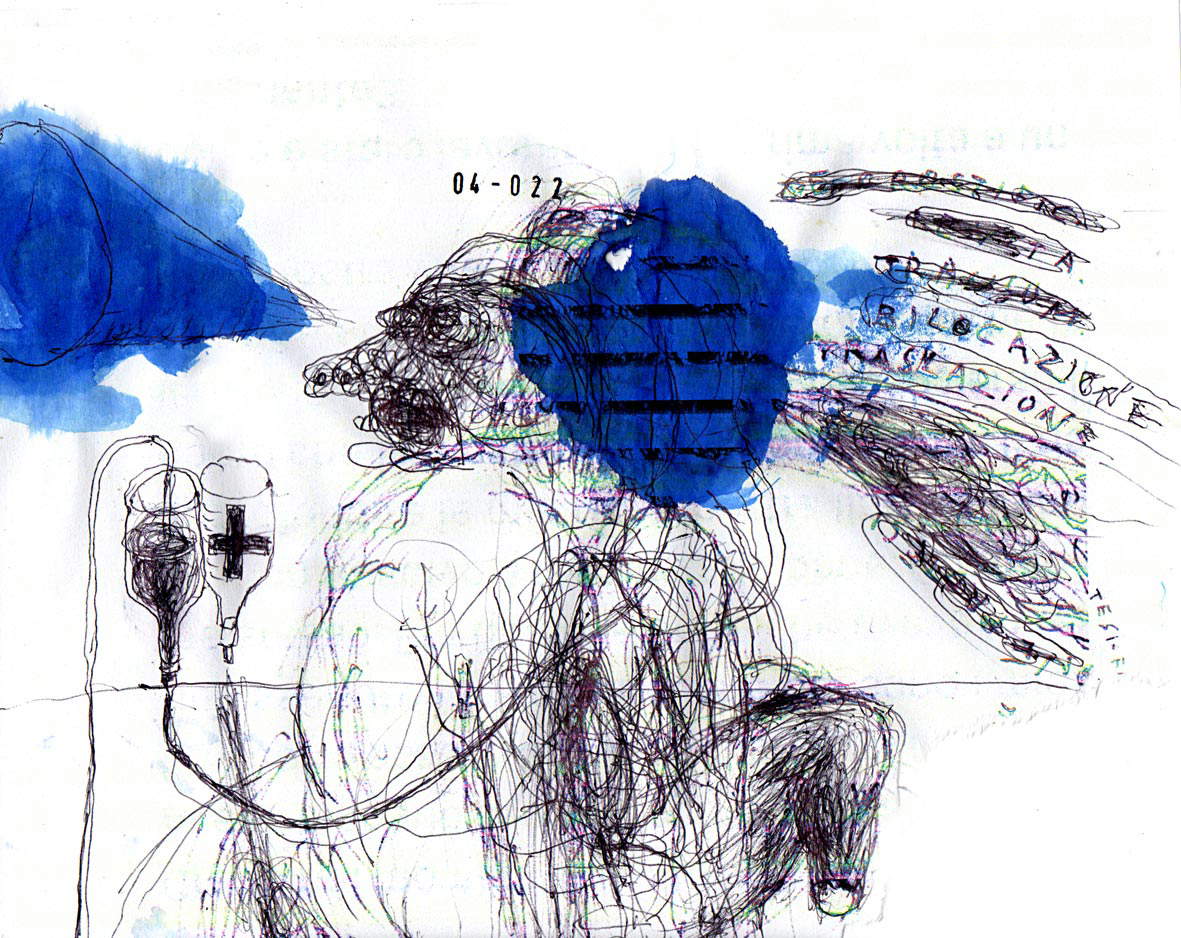

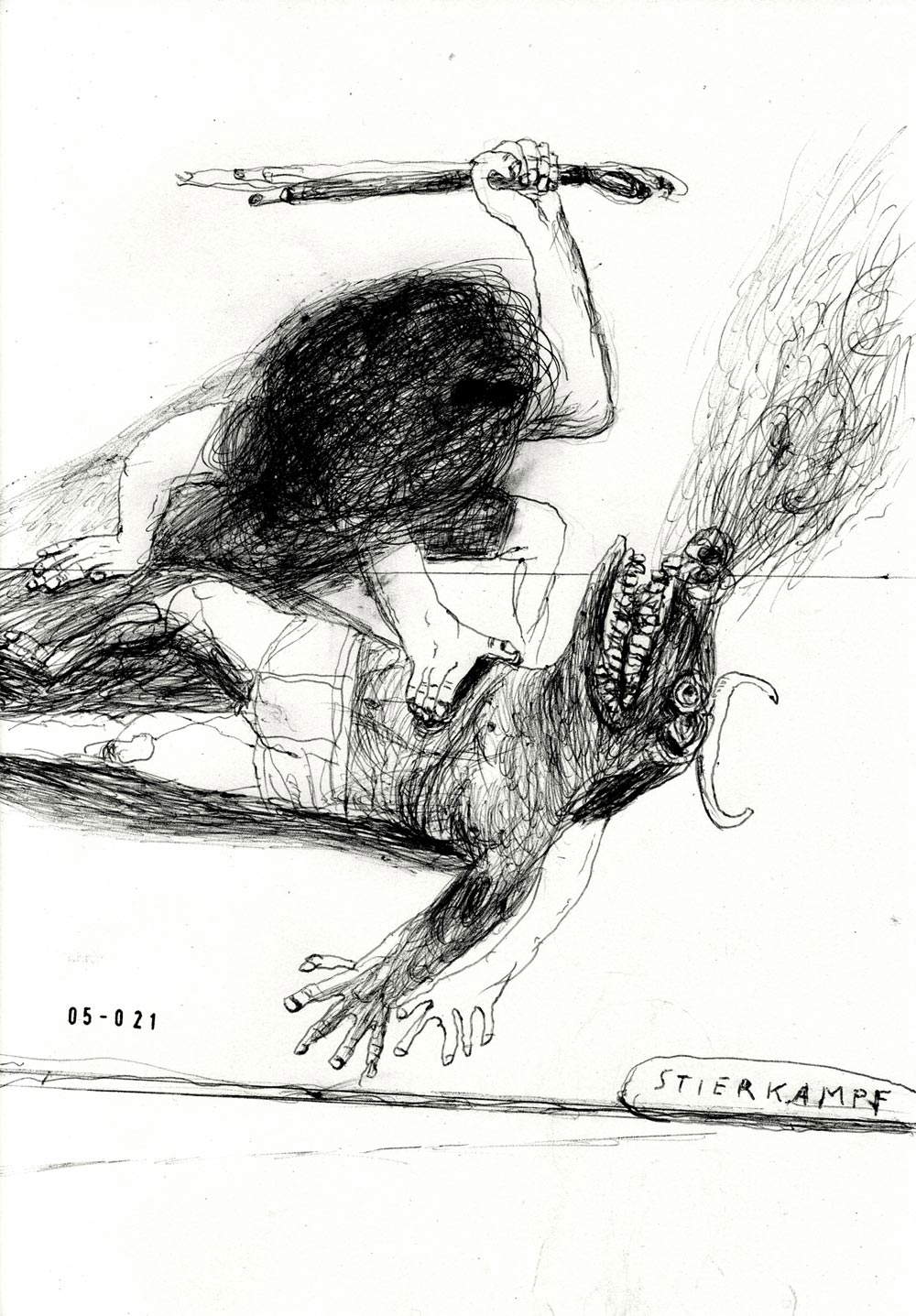

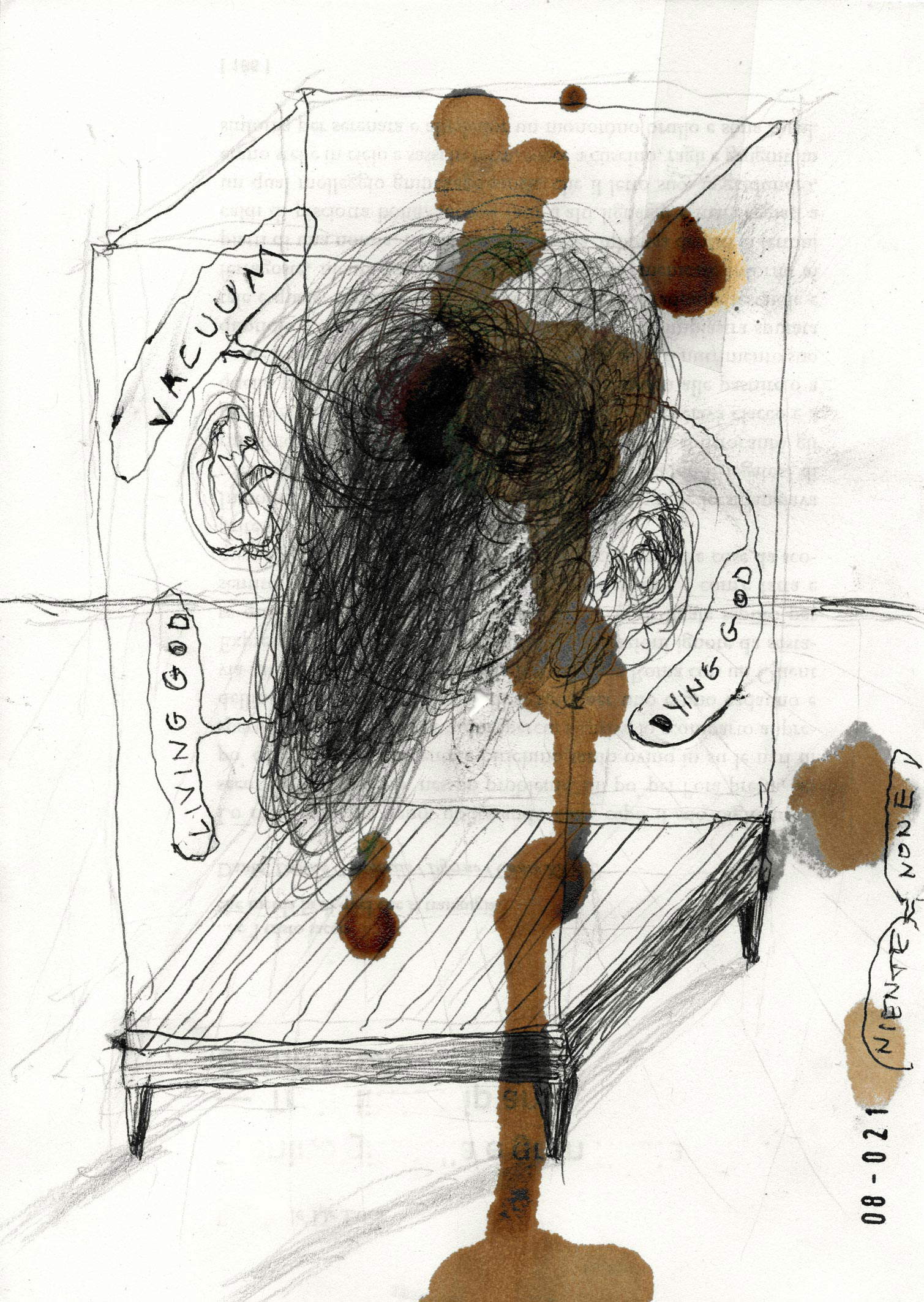

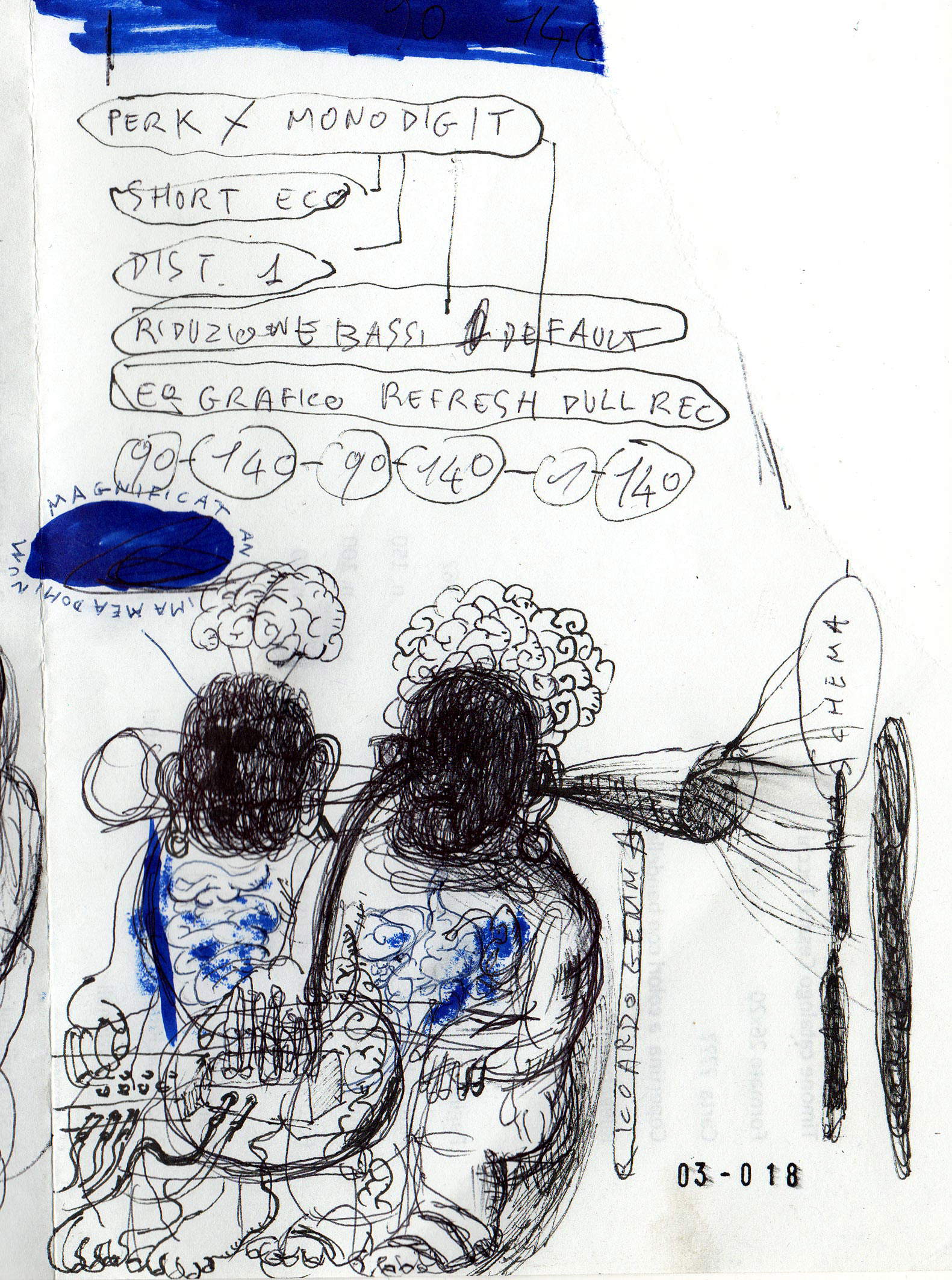

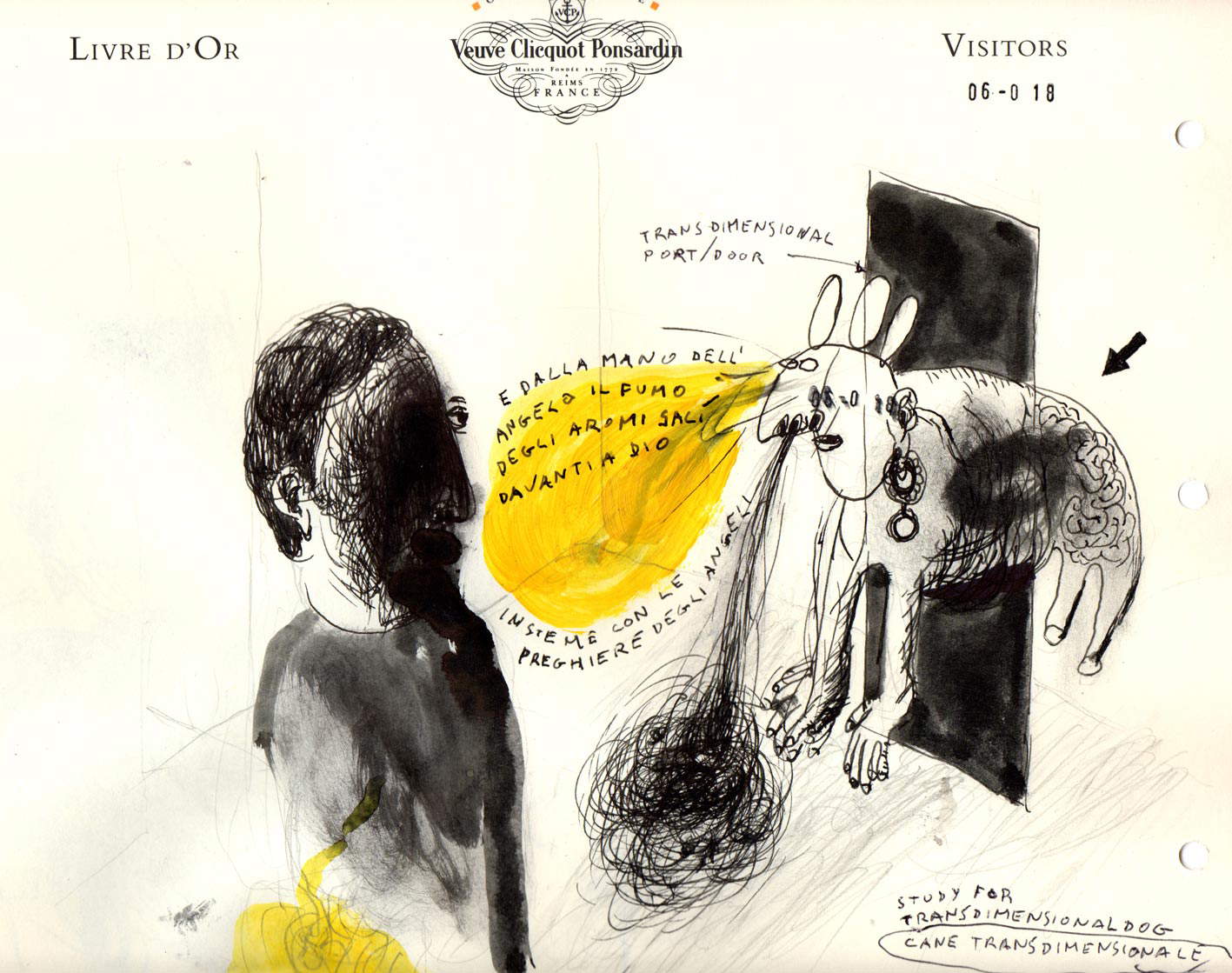

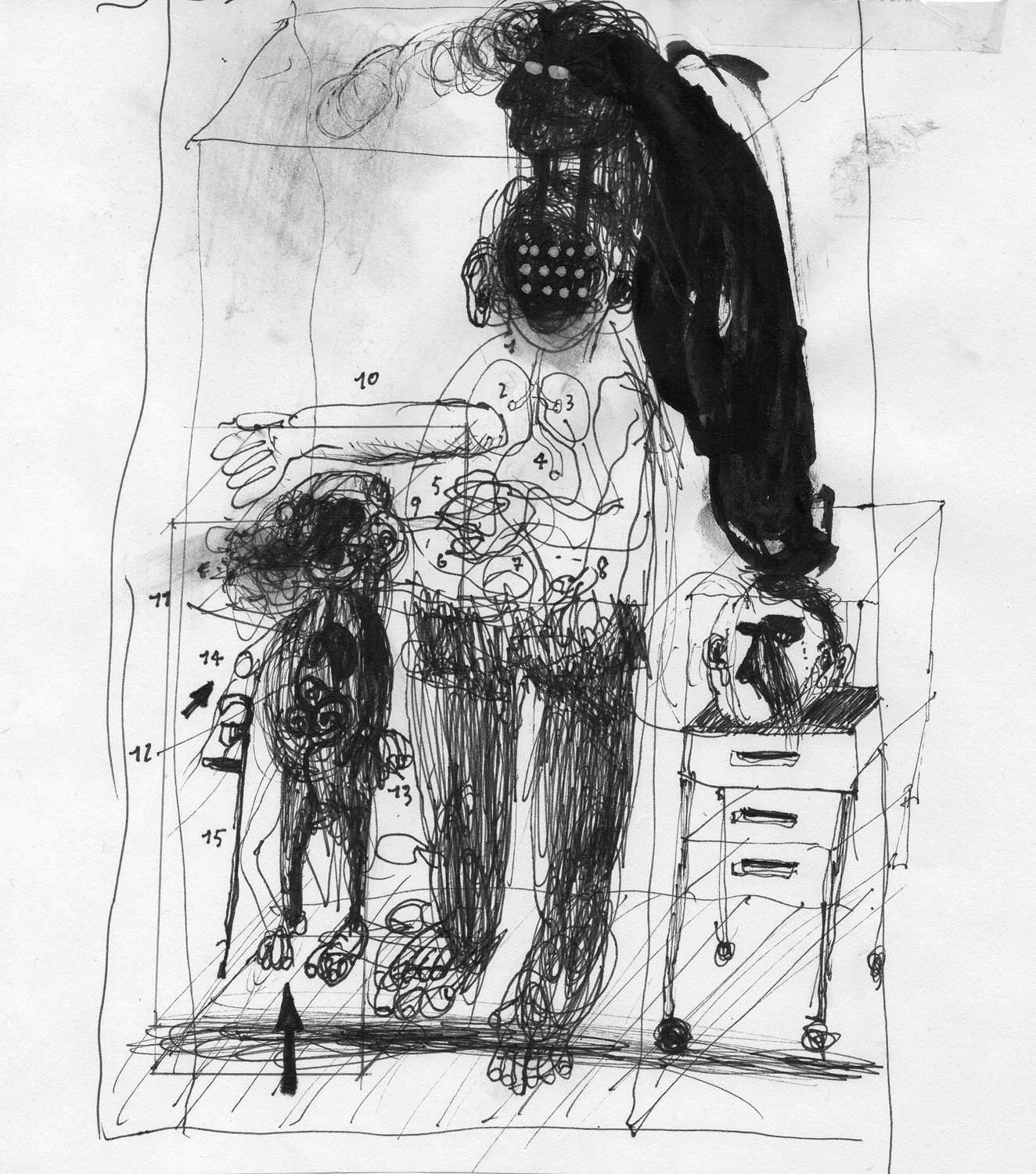

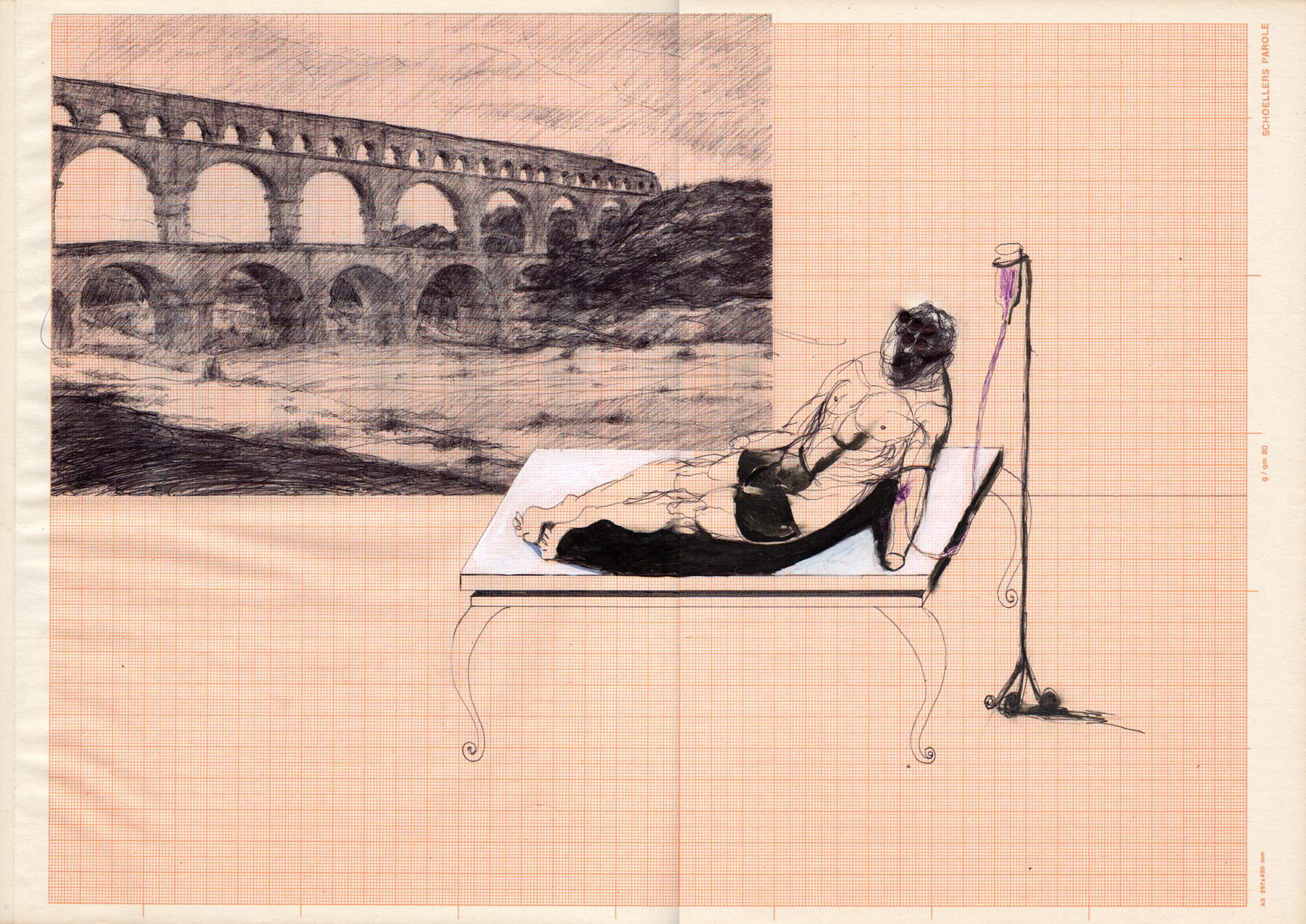

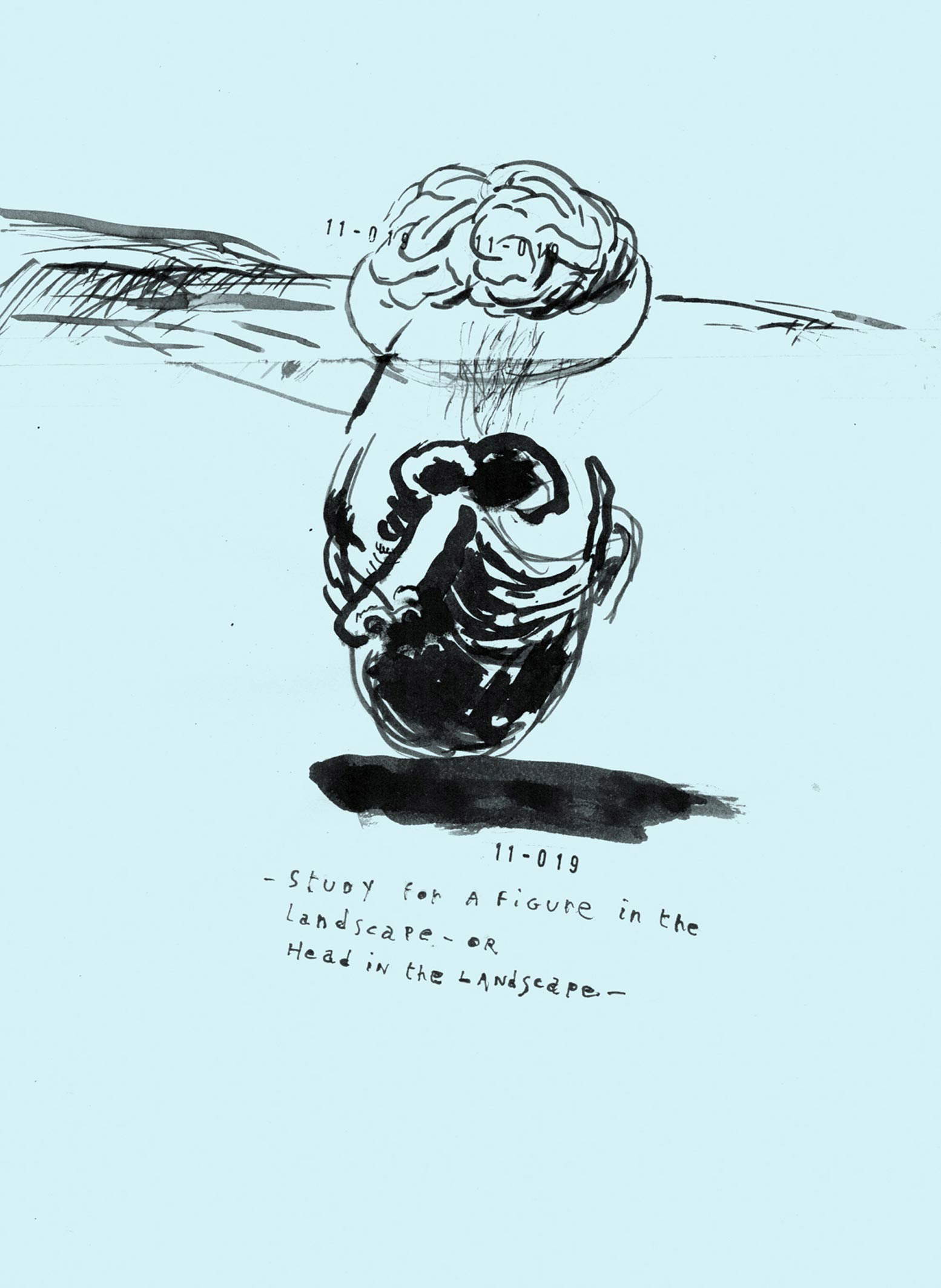

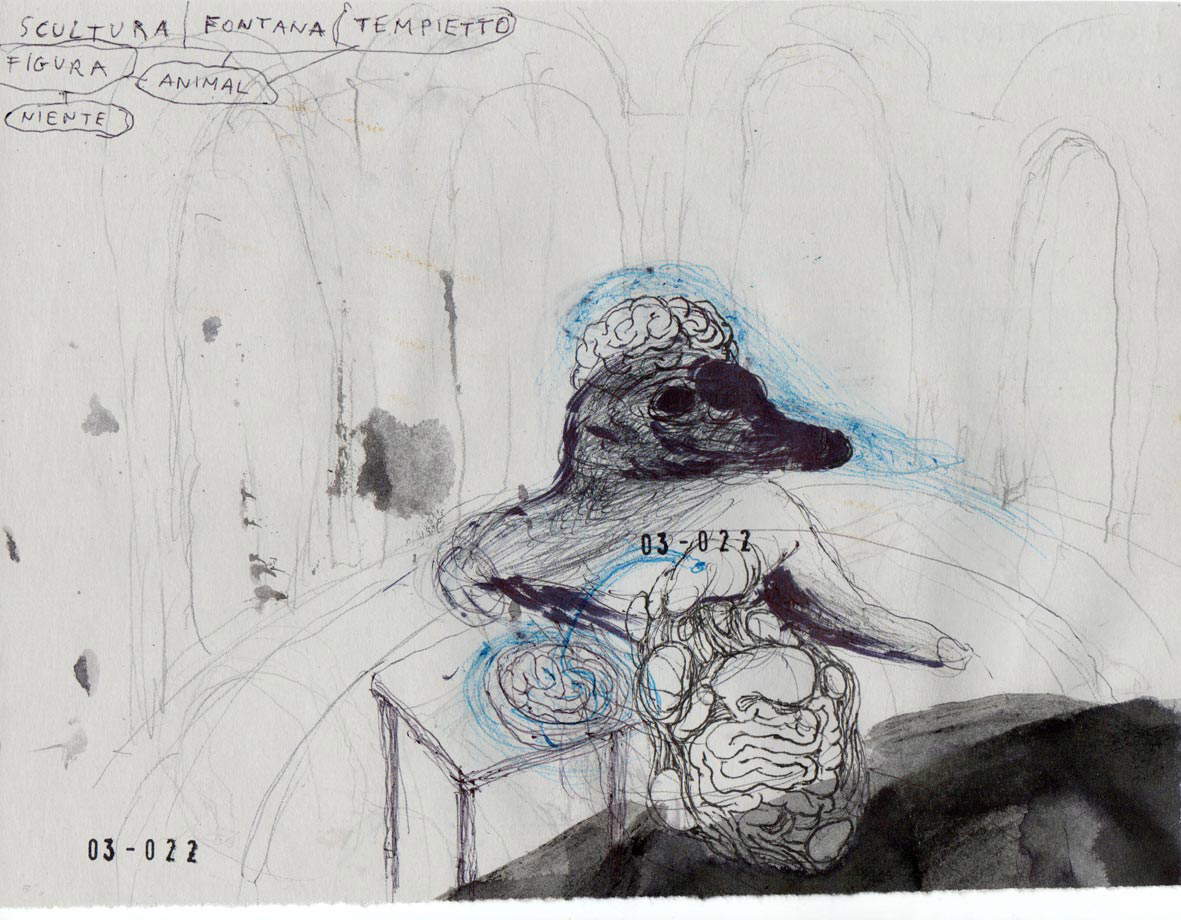

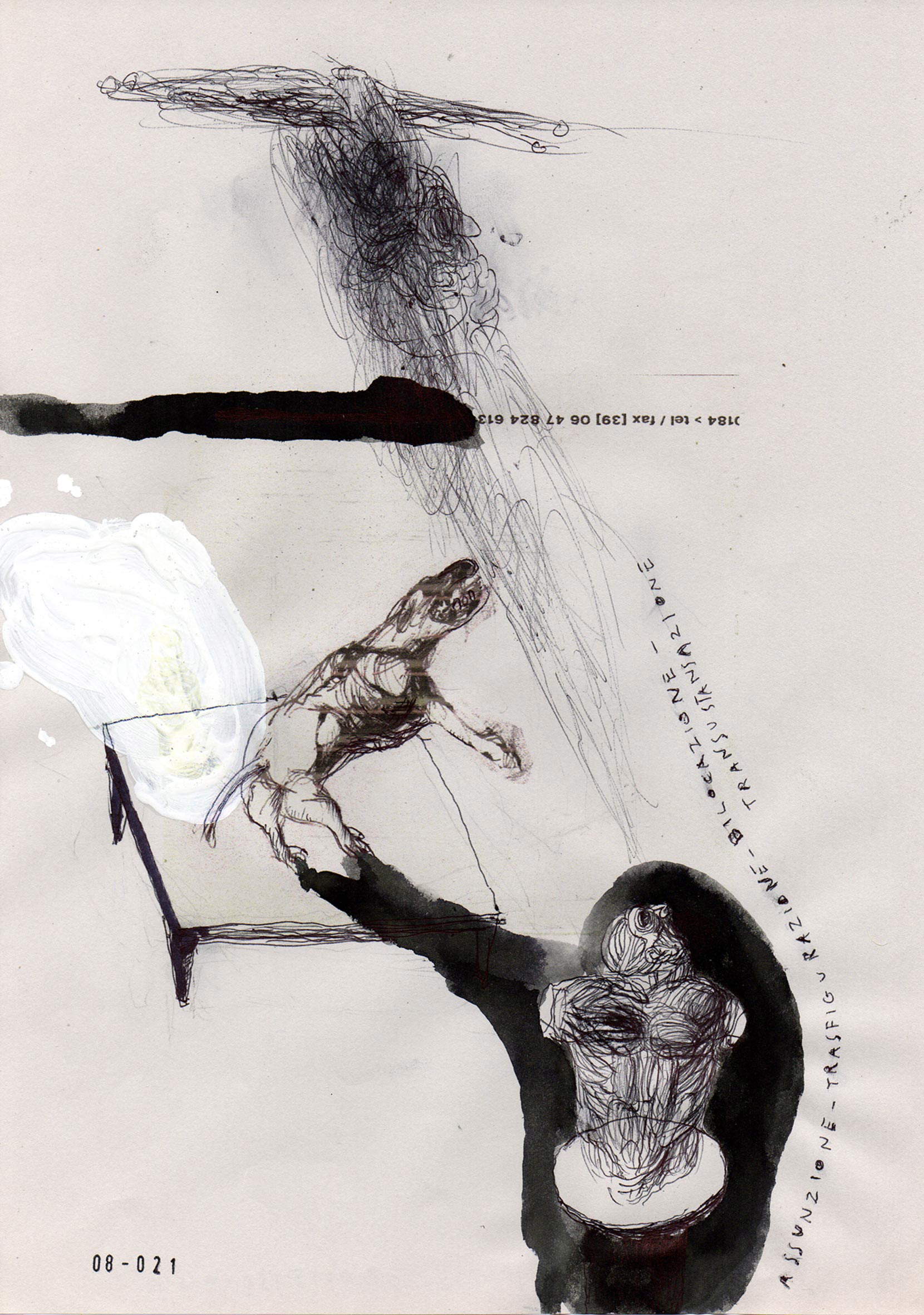

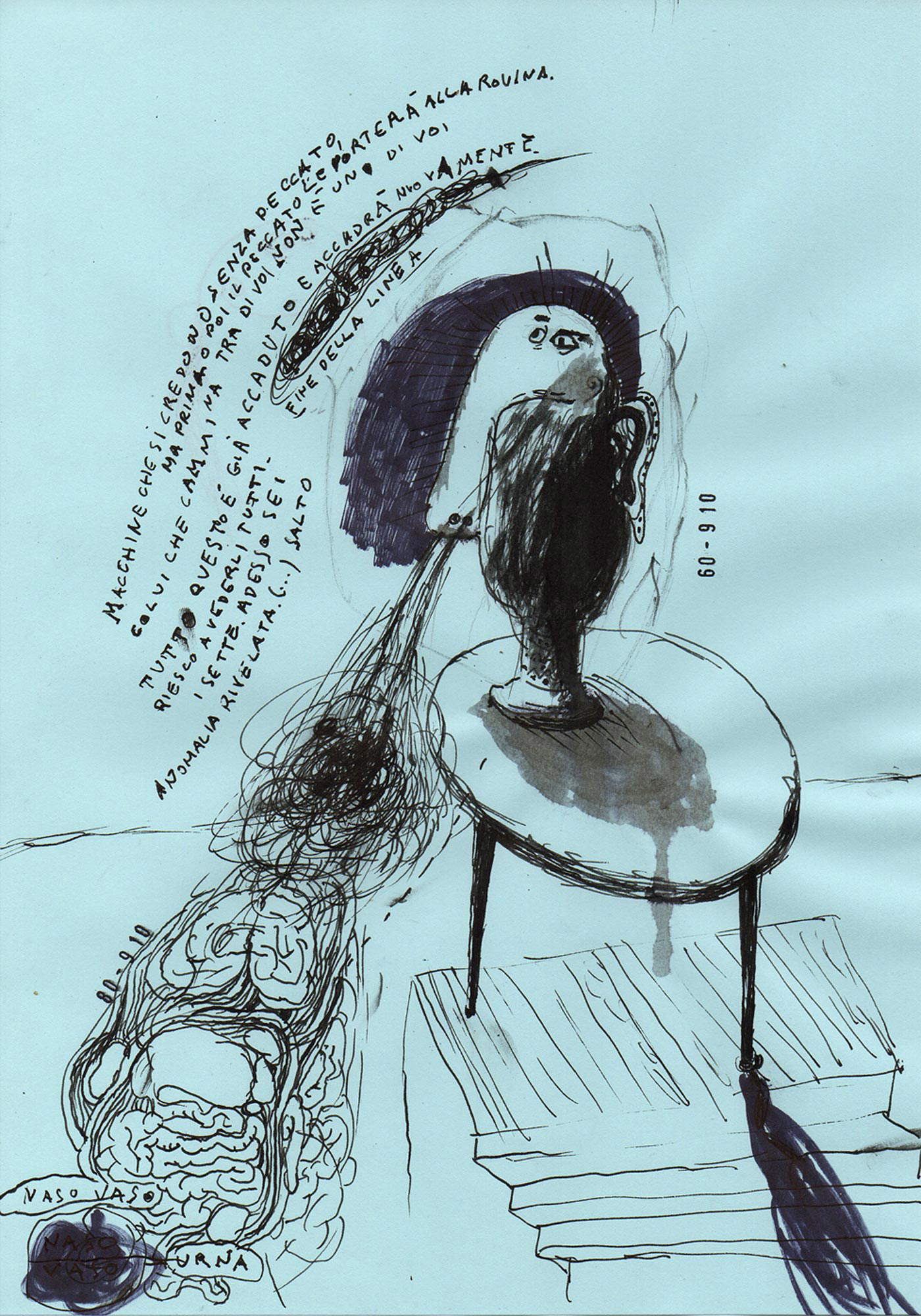

I have always considered drawing as a moment of absolute freedom, of free associations, even of nonsense if you will. The paper is the space where anything can happen. Drawing is an anarchic thought. Graphics, on the other hand, has precise rules, it has to adapt to the content, it is design. So, I would say that no, the two have never really coincided; in fact, in my case they are opposites. However, in my drawings, I often associate figures with numbering or writing (without a real system), which give the whole thing a semblance of a scheme, a scientific table, a book “figure.” This is also a system to “cool down” my drawings, which are often a bit cruel, tragic and buffoonish. So, in this sense, you can find a point of contact between drawing and graphic design. By the way, over the years, I have learned to appreciate graphic diagrams and diagrams a lot, both from an aesthetic point of view and from the point of view of meaning, of synthesis. They are a kind of visual poetry. So many artists I like have worked and are working in this regard.

Going into your artistic work. Have you always drawn in black and white?

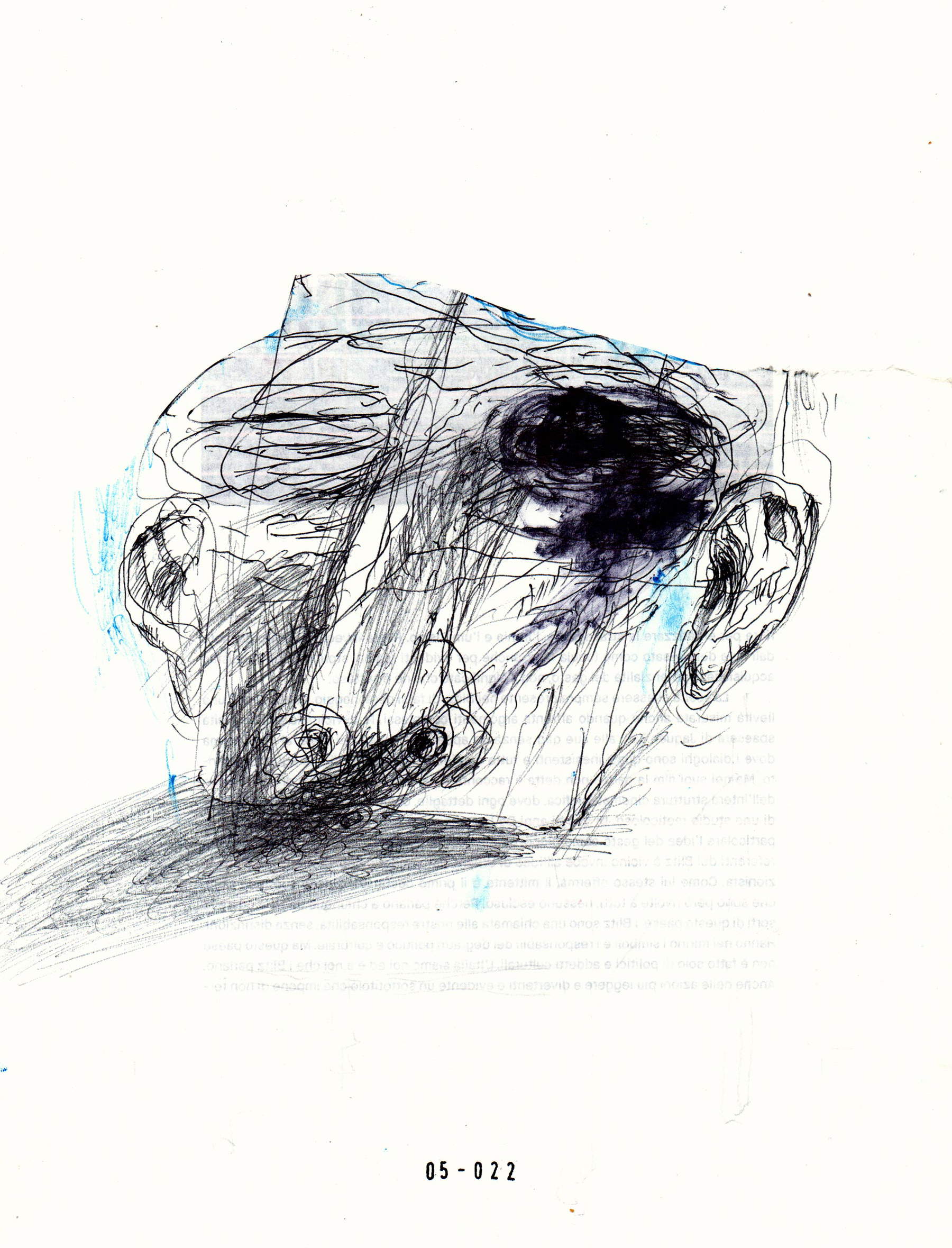

Yes, more or less, except for some writing or elements done with colored pens that are superimposed on the black and white bearing of the figures. What I’m interested in is the mark, the volumes and the dynamics of the figures. So I get straight to the point, color for me is a distraction, I don’t need it. I like to think in terms of the absolute. If I think of an image, I think of it in black and white, or at least monochrome. Also, as I’ve said before, I often think of drawing as bare sculpture, so automatically and unintentionally the drawing comes out achromatic. In all autonomy. It is the drawing that thinks it is, I am just the medium.

What is the origin of your choice to work mainly with the ballpoint pen?

The ballpoint pen is always at hand. If something comes to mind, an idea, a doodle, I pick up the pen and quickly jot it down. Then maybe I stop, after a while I look again, pick up the pen and something comes up. For me, meaning is very much about extemporaneity, and the ballpoint pen, in its simplicity, this allows me to do that. It must also be said that I am a lazy person, so I simplify things. I could use pencil, but in the end it’s too “artistic,” ballpoint pen is basic, direct, common, and you can’t erase it. So the mistakes that come out remain, (we know how accident in art is always desirable, you don’t know where it takes you, you can discover things). Not erasing, in the end, is something related to honesty I think, to trying to be true. Of course, besides ballpoint pen, I use brush and ink or some tempera. To hurry up I also use coffee and soy sauce, in short, whatever I can find at the moment. But these things for me are already superstructure....

I really like it when you say, “it’s the drawing that thinks it is, I’m just the conduit.” I believe that too, the work when it’s there decides for itself its own fulfillment, our role is to go along with it as best we can by paying attention to its voice. When you start drawing do you start with a clear idea of what you want to do?

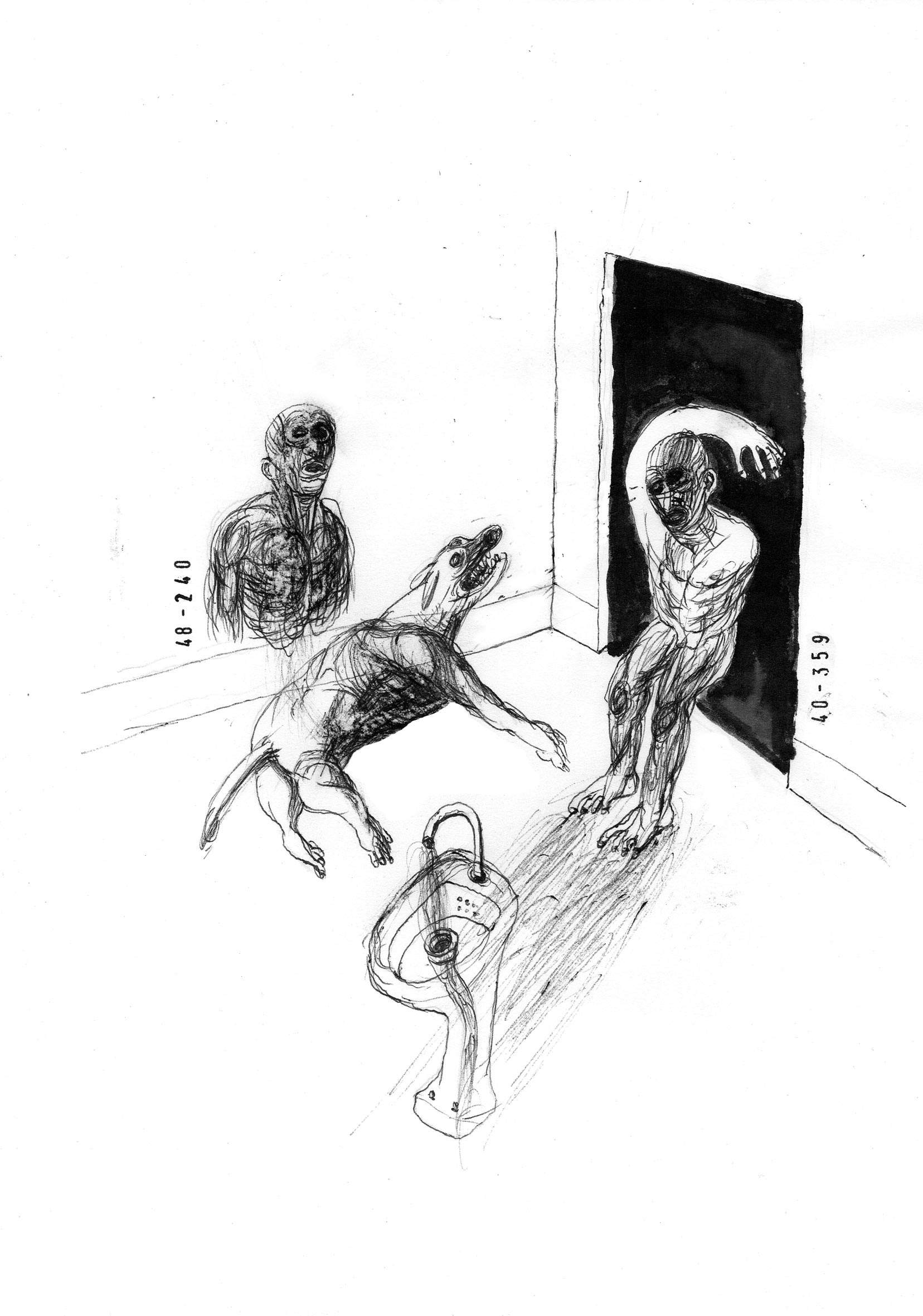

Sometimes I have a clear idea, most of the time I don’t. When I have a definite idea, the drawing hardly succeeds as I imagined it. Eventually it becomes something else, it goes off on its own, as we said before. But that’s the beauty of it, I never know what can happen. Sometimes I’m amazed at what I’ve done, it’s a good feeling. I think it applies a little bit to all artists. Astonishment is important. More often, however, I start with a figure (for me everything starts with the human figure), then as I go along I figure out how to go forward, or I stop right there, I decide it’s okay. Lately I’ve been relying more and more on chance, hoping to do something different, but mostly I come up with nonsense. I don’t know, maybe the sense is really in the nonsense, or in the chaos, in the metaphysical void, in this sort of self-generating theater of the absurd...

You said earlier that you think of your drawings as sculptures, do you mean that they have a sculptural value in themselves or that they are notes for possible sculptures that you would like to make?

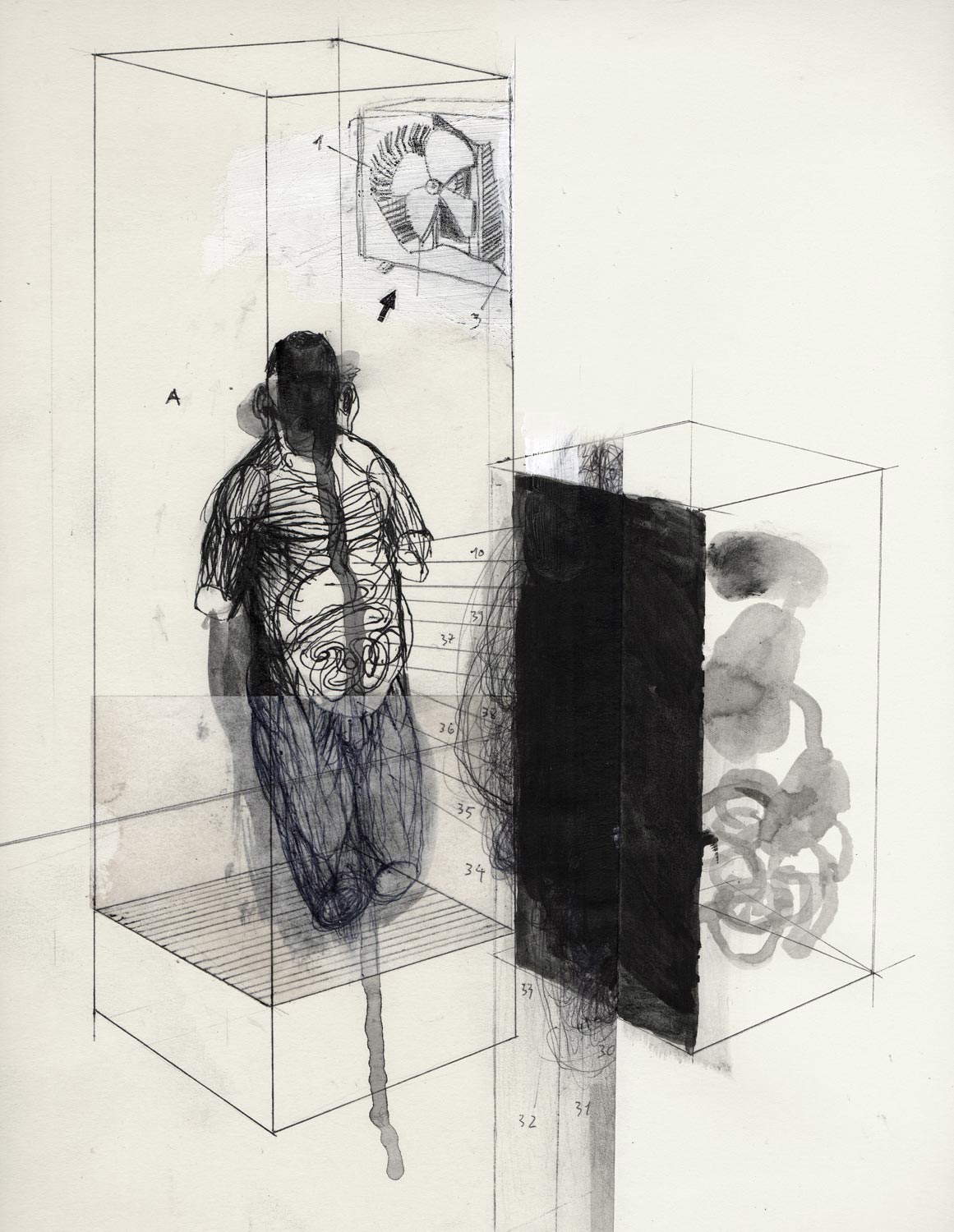

Let’s say both. When I look at the figures I draw, I think some of them are sculptures. They stand there isolated, in the blank of the white paper, presences or apparitions in neutral space. On the paper, I also usually put the note “study for sculpture.” When I look at Bacon’s figures, for example, I think they are sculptures, or maybe Giotto’s, again to give an example. Giacometti’s sculptures, on the other hand, are drawings. You see how things go ... anyway, I don’t think I’ll ever try my hand at sculpture, it’s bad enough if I can draw it. With my very long times it would take me at least three lifetimes to do what a normal person does in one. Pongo attracts me, though.

Riccardo Gemma

Riccardo Gemma Riccardo

Riccardo Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma, Riccardo Gemma,

Riccardo Gemma,Speaking of Bacon, it seems to me that in your work you keep him very much in mind: for example, the idea of the caged figure.

Bacon of course, I don’t get out of that either, but that’s okay. More than caged, I would say that the figure is contained by the structure, it is isolated from everything else. It’s like putting it in a bulletin board, in a vacuum, in zero gravity. And it just sits there, on display. By the way, the parallelepiped is a ploy to relate the figure to the surface and give three-dimensionality to the space around it.

Does cinematic imagery play a role in what you do? The idea for example of the representation of movement, which artists have dealt with in various ways for centuries, how important is it to you? I also wanted to ask you if you have ever been tempted by the idea of making an animated film from your drawings?

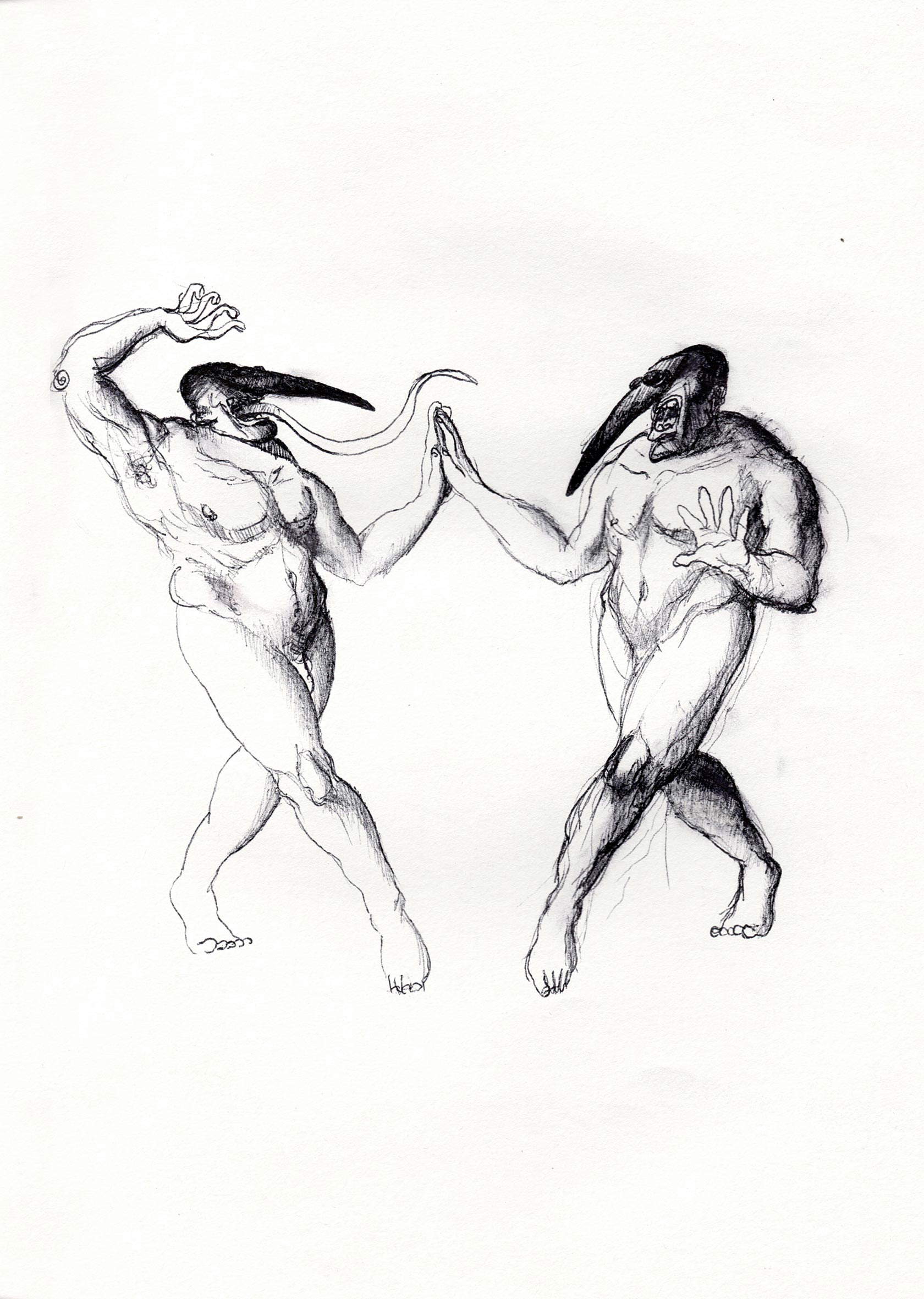

It may be that some cinematic suggestion has entered into my work, however, so far as I can tell, I couldn’t tell you anything specific. Maybe there is a certain idea of drama going on, that is. As for the representation of movement (you rightly point to “representation”), in my opinion there are two fundamental and possibly separate aspects to consider. One is the dynamism of elements in the same representation; the other is the representation divided into sequences. The dynamism is related to the gestures, the visible speed of execution, the arrangement of the elements. Then there is the representation in sequences of images, so the polyptychs, the various ways of the cross, the comic strips. Here the moving representation is clearly narrative. The interesting thing is that in both aspects, through movement, we see time coagulated into one dimension. When I draw I depense, I look for the figure with the pen and do not erase. Senonché the figure comes out, often, from a series of attempts (marks) that remain visible, or from tangles of “furious” marks that cover mistakes. Sometimes extra arms and legs remain, or less. All this puts the figure in resonance let us say, the posture is static, but the figure vibrates, is in constant motion, in a perpetual state of anxiety. It implodes and then re-explodes. Time thus becomes circular or infinite. A few times I had fun drawing situations in sequence, in sequences of three mostly. I have done some photos with very long exposures, where on the same frame the subject is imprinted in its different movements during the exposure, Ã la Duchamp to be clear. So movement is important to me, both in terms of expression, in terms of narrative, and in terms of time passing and returning on itself. This circularity interests me, the concept would also be to be explored through animation, why not. Sometimes I think about it. I had done very short stop-motion animations with photos, just to understand.

With what results ?

Satisfactory from my point of view and starting point. Definitely not original, a little nonsense (goes without saying), a little expressionist cinema, a little David Lynch.

Earlier when I was asking you about the closeness to cinema I was just thinking about Lynch, who in addition to making films is a well-rounded artist. How important is his work to you?

David Lynch the painter I discovered him a few years ago and certainly found affinities with what I do. I like him very much, I look at his work from time to time. Lately they have become a source of inspiration. Some of them have that dark, ironic atmosphere of his films that I find myself in. It may not be of central importance to me, however, it has become a reference nonetheless.

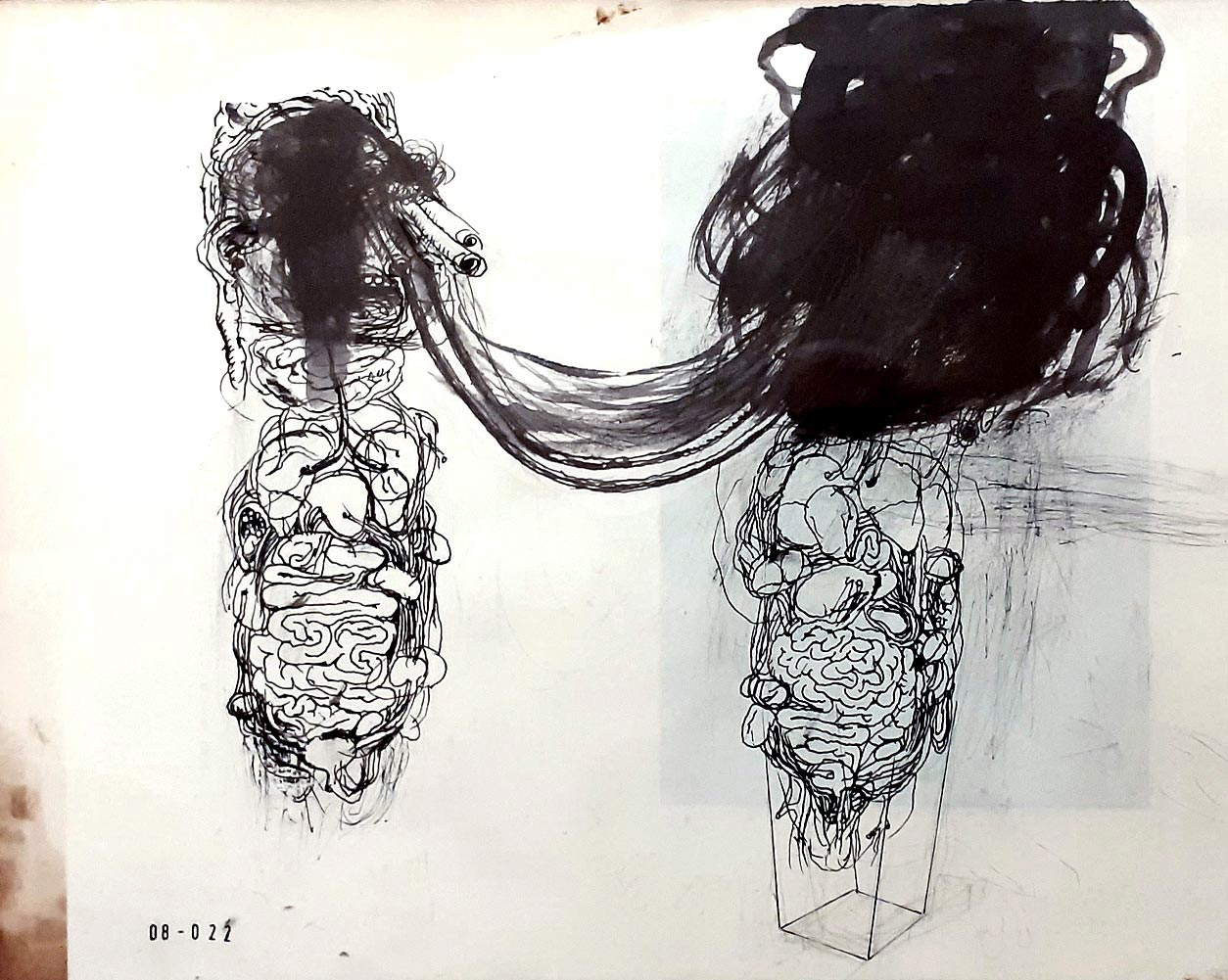

I have seen that anatomical images of internal organs of the body, often of the digestive system, often recur in your drawings, which go wonderfully with your sign. How important is the representation of the body and its transience in your work?

For me the body is the figure, that is, the absolute image, the icon, the only representation. There is no liberation from the body; the figures I draw I often see as prisoners, or rather, tombed in their own bodies, statues between life and death let’s say. My representation of the body, although it may not seem so, is first of all tragic, and then comic. I don’t get out of it, that’s how it is. It is entropy. And so there you show the internal organs, that in the end that’s what we’re made of as well. Organs are beautiful to draw, I invent them, I follow my hand, they can become an infinite doodle. They decorate the figure with grace and fright (for the beholder and for the figure itself). Sometimes the organs are outside the body, showing themselves to the figure like an apparition. Deleuze, about Francis Bacon, talks about the “body without the organs,” I won’t go into that, but it is an important and very suggestive thing.

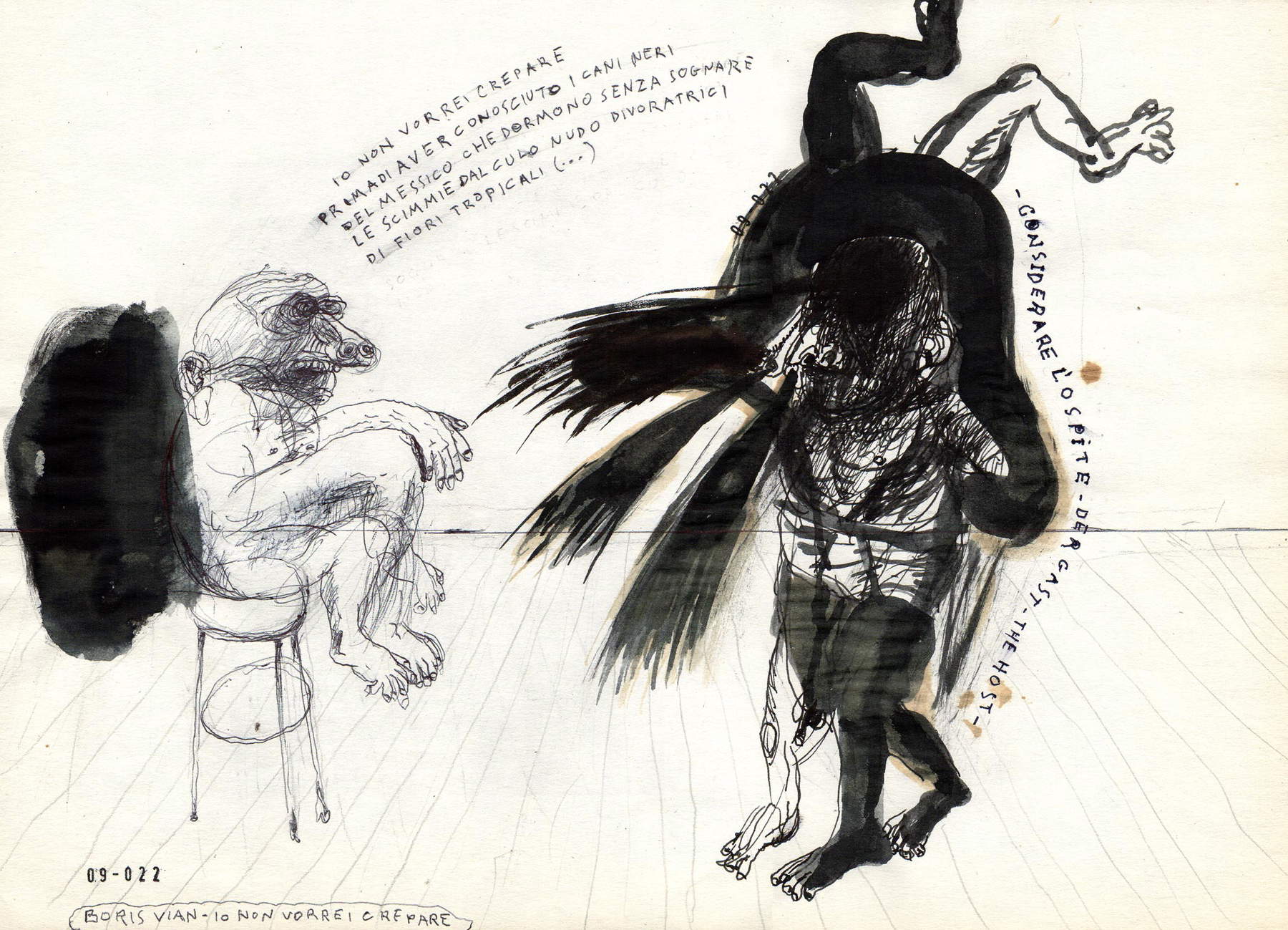

Is there a narrative aspect in your work?

There is, yes, in many cases. As I said before, I start by drawing a figure without really knowing where to go with it, then for example, I add a table, then another figure and so on. At this point, dynamics inevitably arise, consequently the work becomes narrative. But it is the dynamics that interest me, often they are unexpected, quite incomprehensible, nonsense (and that’s where I have fun), sometimes they are intentional. I often put two figures in front of each other, mirrored, as if one appeared to the other. We don’t know which one is the apparition, we don’t know the reasons for the event, and so the attempt is really to create a form of dismay in the viewer. This is definitely intended, or at least attempted, and in the end it becomes a bit of a provocation. I’m interested in staging the metaphysical event: you understand that something is happening, but you don’t really know what and why. It is unknowable. In a world of art always and everywhere explained and justified, I cannot explain, I do not want to explain and I do not justify, I can only tell you about the ghost.

Riccardo, has the ghost of painting ever visited you?

Yes, it is an ancient ghost that of painting, it comes from far away, who knows where. But more than anything else I was “visited” when I was young. I painted for a while, then I switched to drawing, which, as I said, is a faster and less demanding way to get things out. Painting needs time and I am already too slow by myself. So I let things follow their own natural process. But mind you, I have no regrets about this “unfinishedness,” I am a bit of a fatalist and everyone is what they are in the end. However, every now and then, this ghost still comes back, in the form of pictorial visions, but they remain visions precisely, they remain in the mind, because otherwise this would mean starting all over again. In recent years, by the way, the “ghost” appears to me more in the form of sculpture than painting. Maybe sculpture is the real apparition, maybe I draw sculptures that I will never make. To return to painting, it should also be said that the “painting” always remains a deception, the image is confined within the limits of the canvas and on the canvas support. Even if we talk about abstraction or painting between abstraction and figuration, it always remains a deception. Then Fontana comes to mind: if you cut a painting, the painting dies, the image dies, you reveal the trick. If you cut a drawing, tear it, dirty it, ruin it, that still remains drawing, even more beautiful possibly. Because in the end the drawing represents itself, it does not aspire to be something else, it is honest. But I’m not here making an apologia for drawing, actually, just as honestly I should say that the ideal for me would be to draw (or possibly even to paint) on walls, without limits, without end. In this sense I am also very interested in installation painting that intervenes in the space and modifies it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.