Dürer, a great visionary fatally attracted to Italian art. Interview with Diego Galizzi and Patrizia Foglia

UntilJanuary 19, 2020, the Museo Civico delle Cappuccine in Bagnacavallo (Ravenna) is hosting the exhibition Albrecht Dürer. The Privilege of Disquiet, an exhibition that explores, with one hundred and twenty works, the production of the great German artist Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528) in the field of engraving. We caught up with the curators of the exhibition, Diego Galizzi and Patrizia Foglia, and talked with them about some of the masterpieces on display, the souls of Dürer’s art, his encounters, the themes of his art, and his motivations. The interview is edited by Ilaria Baratta.

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I (Melancholia) (1514; burin, 240 x 186 mm, specimen without margins; 2nd state specimen out of two, with characteristics similar to the D variant according to Meder; inscriptions: date and AD monogram in lower right corner) |

IB. In the desire to create exhibitions along the lines of the major international artists who best expressed themselves through the practice of engraving, the exhibition dedicated to Albrecht Dürer is intended to be a tribute to the “founding father” of graphic thought. Why can Dürer be considered the one who first took the art of engraving to the highest level?

DG-PF. Max Klinger, an artist to whom we dedicated last year’s exhibition, in his treatise Malerei und Zeichnung published in 1891, says that Dürer was his master in the art of the stylus, the only medium of expression, the only artistic language capable of depicting the world by giving it intensity and meaning. Dürer’s work stands at the beginning of a long history in which engraving has been able to bear witness to the deepest and most complex aspects of man’s reality, of his existential vicissitude; he was also a skilled master in technique, assimilating what he could from those who had preceded him by shaping a language of the sign that became inescapable after him. He was a modern artist also in this extraordinary ability to make engraving an accomplished language, no longer at the service of illustration, not for the sole purpose of mere circulation of motifs, but full and meaningful Art.

The title of the exhibition is Albrecht Dürer. The Privilege of Restlessness, a statement intended to summarize Dürer’s own character, that is, a multifaceted personality when observed both as a man and as an artist. How were the different souls of Dürer presented in the exhibition? Why is restlessness a privilege in Dürer’s case?

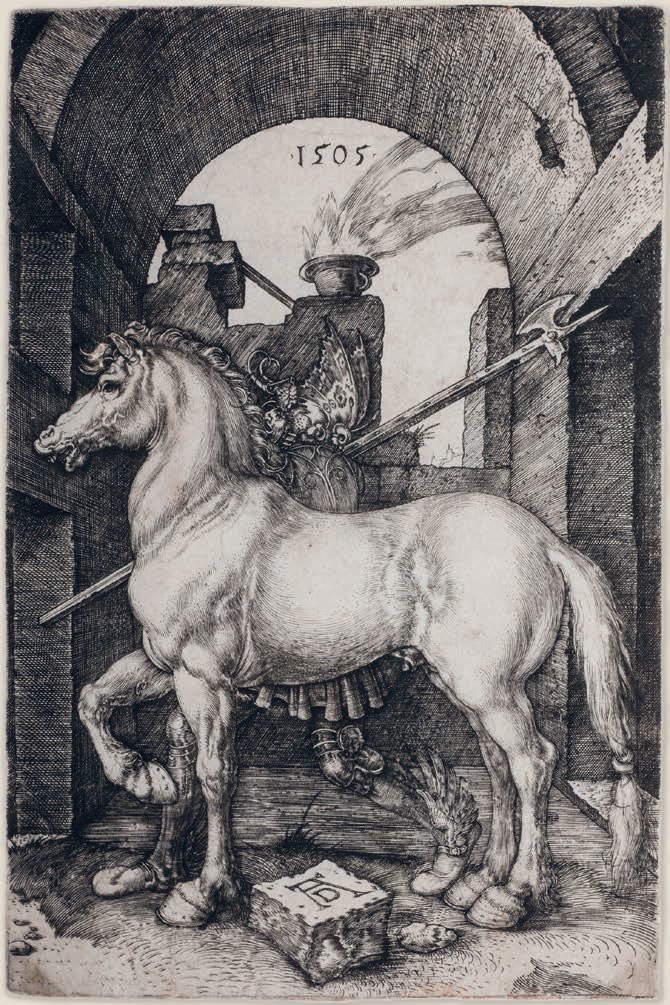

Dürer lived a constant tension between conflicting psychological impulses. In some ways he was one of the keenest and most patient observers of reality, as evidenced, for example, by his superb and meticulous burins, yet he was a great visionary, capable of giving form and force to a great deal of inner imagery. The imaginative cycle of theApocalypse bears witness to an imagination bordering on the irrational, yet it owes its extraordinary power to the credibility of those images, the steadiness of the modeling, the variety of expressions, and the “rational” study of the achievements of the Italian Renaissance. As convinced as he was that artistic creation was a kind of mystery, a gift infused from above, his artistic story is characterized by a constant aspiration toward the achievement of rational principles. The exhibition itinerary slowly accompanies the visitor among these conflicting forces, turning the pages of an unstable, eternally unsatisfied, sometimes contradictory artistic identity, capable of moving from the nonsense of the Ship of Fools, or the turbulent Apocalypse, to the true dramaturgical trials of the Passions of Christ, to the most extreme outcomes of his research into the “scientific” representation of bodies and space, so well represented by masterpieces such as the Little Horse, Adam and Eve or the St. Jerome in the Studio. In this extraordinary adventure of knowledge lies his restlessness and, at the same time, his privilege: hence the choice to title the exhibition with a quotation taken from Henri Focillon, who in his inspired essay on Dürer summarizes in the “privilege of restlessness” the greatness of the Nuremberg artist.

One of his most famous masterpieces is Melancholy, which is featured within the exhibition itinerary. The work encapsulates a true spiritual self-portrait of the artist and also reveals his awareness that approaching art and the world using only reason was not appropriate for his time. Could you elaborate more on these aspects concealed in Melancholy?

This work by Dürer represents the pivot on which his entire conception of art plays; that is why we wanted to close the exhibition itinerary with it, accompanying the visitor to the thresholds of a possible understanding of human nature and its many facets, the thresholds of a mystery that not even aesthetic perfection, the beauty of nature, reason, and art are able to fully comprehend. There are depicted numerous symbols and references to the Neoplatonic theory of the four humors or temperaments based, since antiquity, on the belief that man was dominated, by mind and body, by four fluids linked in turn to the four natural elements, winds, seasons, and phases of life. The perfect balance between these four temperaments, wrath, phlegm, blood, and melancholy, was possible only ideally and for an almost immortal being, becoming instead unattainable to man because of original sin. One of the moods always prevails over the other defining for each of us our own personality. Panofsky admirably describes this work, for which there are myriad esoteric, magical, irrational interpretations. The work follows a long iconographic vein, often also linked to the medical or philosophical sphere, but Dürer creates something unique and unrepeatable: sitting and reflecting is a higher being, surrounded by the elements of creation, since the artist is a “creator” on a par with God, as well as scientific instruments, useful for pursuing full knowledge of the rules of nature. There are references to astrology, astronomy, mathematical sciences, and technology; it is his gaze as a careful theorist and scholar that comes into play in this depiction. Can reason, study, knowledge ever bring man to perfect wisdom and understanding of the whole? There is discomfort but also acceptance, the melancholy of the last days, there is fatigue, pain, but also a deep reflective attitude. Beauty, perfection, are also impossible for him to achieve: here the ingenious hand of man stops, before the inscrutable divine creation.

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Little Horse (1505; burin, 165 x 108 mm, specimen without margins; single state specimen, in variant A according to Meder; inscriptions: upper center date; lower center AD monogram; watermark: bull’s head and triangle - M. 62; BR. 14881; Private collection) |

![Albrecht Dürer, Adamo ed Eva (Il Peccato originale) (1504; bulino, 249 x 191 mm, esemplare privo di margini; esemplare di III stato su tre, con caratteristiche simili alle varianti A, B o F secondo Meder; iscrizioni: nel cartiglio, in alto a sinistra “ALBERT / DVRER / NORICVS / FACIEBAT / [Monogramma AD] 1504”; filigrana: testa di bue sormontata da una freccia - M. 62; Collezione privata, Brescia) Albrecht Dürer, Adamo ed Eva (Il Peccato originale) (1504; bulino, 249 x 191 mm, esemplare privo di margini; esemplare di III stato su tre, con caratteristiche simili alle varianti A, B o F secondo Meder; iscrizioni: nel cartiglio, in alto a sinistra “ALBERT / DVRER / NORICVS / FACIEBAT / [Monogramma AD] 1504”; filigrana: testa di bue sormontata da una freccia - M. 62; Collezione privata, Brescia)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2020/1211/albrecht-durer-adamo-ed-eva.jpg) |

| Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve (The Original Sin) (1504; burin, 249 x 191 mm, specimen lacking margins; specimen III state out of three, with characteristics similar to variants A, B, or F according to Meder; inscriptions: in cartouche, upper left ALBERT / DVRER / NORICVS / FACIEBAT / [Monogram AD] 1504; watermark: ox head surmounted by an arrow - M. 62; Private Collection, Brescia) |

|

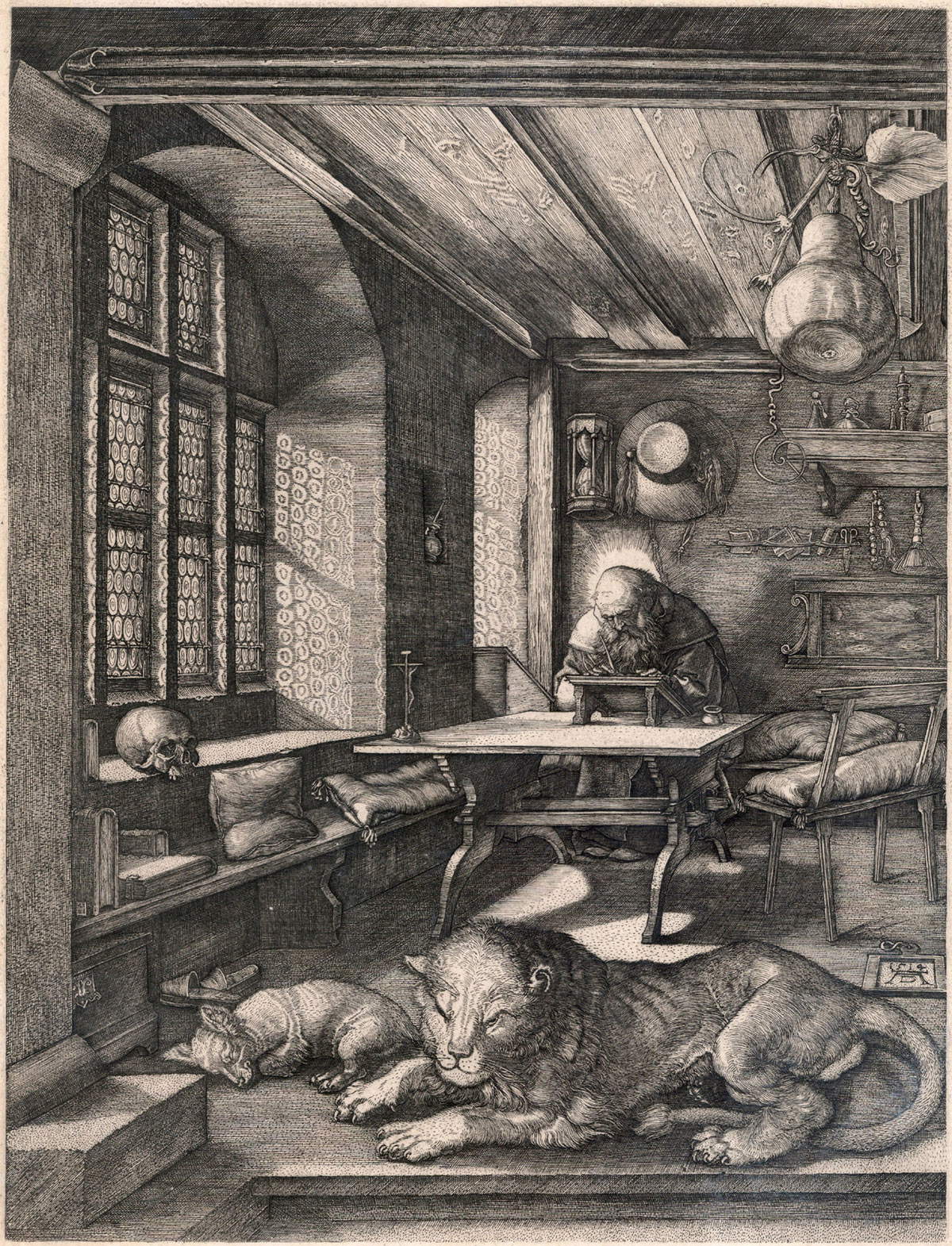

| Albrecht Dürer, St. Jerome in the Study (1511; woodcut, 235 x 160 mm, specimen with small margins; single-state specimen, with similar characteristics to variant E according to Meder; inscriptions: date lower right, monogram AD lower center; Pavia, Musei Civici) |

Dürer continually felt a desire to achieve perfection, focusing above all on beauty. What was beauty for him? Looking at Italian Renaissance art, where beauty was, one might say, the common thread in the representative works of this era (think of Raphael, Leonardo, Botticelli...), how much did this influence his ideal of art?

The encounter with the Italian Renaissance was instrumental in making Dürer the absolute master that we know. Through this encounter he soon discovered that art was much more than a mixture of natural talent and patient craft practice: it was above all an intellectual achievement. Dürer was fatally attracted to Italy and sought to pursue the Italian masters on the terrain of their achievements. He did so especially in the representation of the human body, to which he strove to infuse grace and proportion, concepts essentially unknown to German art. His quest was primarily dictated by a desire to break out of chaos and arbitrariness (which he blamed on the German artists of the time) in order to acquire the “right foundations” and thus reach the heights of pure form. The canon of beauty to which he aspired passed through the application of the theoretical and mathematical principles of Vitruvius and the experiences of Renaissance artists, forcing the human figure into a complex system of segments and geometric forms, yet he never entirely abdicated from following what he considered the high road in his vision of art, namely, direct observation of reality, something he advised young artists to do first and foremost in his treatises. The Nemesis is the perfect exemplification of this delicate balance: the structure of the Goddess’s body is the result of precise calculations based on Vitruvian dictates, but her features are drawn from everyday life, so much so that that body could be that of a Nuremberg peasant girl. On the other hand, a few years later he moved far more decisively into the quest for the representation of “ideal” beauty with theAdam and Eve, an extraordinary work that manifests his desire to offer an example of two bodies that are not only perfect in proportion, but also modeled with classical convenience.

The exhibition consists of ten thematic sections designed to tell visitors about Dürer’s art through his etchings. Over the course of his artistic career does his art and vision of it change?

He would not be the great genius he was if he had not treasured his experiences, over all those he lived in Italy, in the two trips he made, discovering light, perspective, and the Italian landscape. His confrontation with the artists active in Venice, Rome, Bologna was such a productive confrontation that it revolutionized his conception of art, spurring him to tackle new themes, giving him full mastery of space and composition. A perfect synthesis between the Nordic style and the Italian manner was thus accomplished. His will was to mold his soul, maturing his own artistic inspiration in the light of what was being accomplished elsewhere, not as mere assimilation but as full appropriation. Such significant passages are visible in his production, such as at the beginning of the century the assimilation of the rules of perspective, the mastery of proportions, deduced from the Vitruvian texts, making him one of the greatest theorists of the time. It is his a journey into the full knowledge of reality and its mechanisms, this his “journey,” the element that distinguishes him making him a privileged one and allowing him to achieve a classical balance that is difficult to imitate and is visible even in his last trials.

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Madonna of the Patronage or Madonna of Bagnacavallo (c. 1495-97; oil on panel, 47.8 x 36.5 cm; Mamiano di Traversetolo, Magnani-Rocca Foundation, inv. 581) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Madonna and Child Seated by a Wall (1514; burin, 147 x 101 mm, specimen without margins; single state specimen, variant A according to Meder; inscriptions: right, toward center, date and monogram AD) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, The Holy Family of the Dragonfly (ca. 1495; burin, 240 x 188 mm, specimen without margins; single-state specimen, with characteristics similar to variant C according to Meder; inscriptions: bottom center monogram AD; watermark partially visible but not identifiable; Pavia, Musei Civici) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Madonna of the Monkey (1497-98; burin, 189 x 121 mm, specimen without margins; single state specimen, with characteristics similar to variant E or F according to Meder; inscriptions: lower center AD monogram; Novara, Musei Civici) |

A section of the exhibition illustrates engravings related to the intimate relationship between the Madonna and Child, also celebrating the return to Bagnacavallo, after fifty years, of the Madonna of the Patronage made by Dürer around 1495 and now housed at the Magnani Rocca Foundation. What kind of comparison can be made between this famous painting and the engravings related to it?

Being able to count on such an important presence in the exhibition as the Madonna of the Patronage panel, we could not help but also offer in the exhibition a moment of in-depth study and reflection on the theme of the Madonna and Child, with a cross-sectional look between painting and engraving. In that section, we do not offer direct comparisons, but offer the visitor insights and tools to make their own. Underlying this is the conviction that, despite the diversity of language, from the juxtaposition of the panel with the engravings and woodcuts we can read against the light a same vision of the Marian image, an attitude devoted to emphasizing the intimacy and complexity of the feelings established between the Mother and her Son. A marked psychological gaze in short. Even more interesting then is the parallel reading of Our Lady of the Patronage with some graphic proofs of the same years, particularly with the Holy Family of the Dragonfly, the Holy Family of the Hares and the Madonna of the Monkey. There are elements drawn from the same figurative backgrounds: Martin Schongauer with his Marian images admired in late fifteenth-century Germany, and alongside the reflections of his first enthusiastic encounters with Italian art, which lend strength and credibility to his works thanks to a new monumentality and the restless animation of the Child, such as that of the Madonna of the Monkey, so heavily indebted to models from Verrocchio’s circle and thus a close “relative” of the masterfully painted one on the Magnani Rocca panel.

What are the most significant works in the exhibition, among the more than 120 on display? What should invite the public to absolutely visit the exhibition?

The exhibition represents one of the most comprehensive exhibitions dedicated to the engraved work of the German Master, a journey into his world and his historical moment. Undoubtedly the masterpieces, the three masterpieces The Knight, Death and the Devil, St. Jerome in the Study and Melancholy I represent the summa of his conception of graphic art and are among the most representative of his research. But in the exhibition we also have the great publishing ventures in which he as a young artist participated, Sebastian Brandt’s The Ship of Fools, with the ancestral fears of the different, madness as a symbol of the tragic nature of human existence, and the great Nuremberg Chronicle, presented in loose sheets but also in a refined illuminated edition. And then the Apocalypse, a grandiose explosion of Dürer’s imagination and a marvelous example of silographic technique. Dürer was a free artist, independent in his thematic choices and inspiration, the first great European artist who knew how to make his inner world converse with that of his own times. Art for him was a projection of his own personality; he was an observer of visible reality but also of its hidden, mysterious side, that of love and sin, fear and trust in salvation. The invitation to visitors is to grasp the subtle web that unites us this great Renaissance “image maker” who was at the same time a passionate scholar of the world, its rules, man and his soul. For his works speak a universal language.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.