Andrea Marini was born on April 19, 1948, in Florence, Italy, where he received his baccalaureate in art and later his degree in architecture. He still lives in Florence and carries out his creative activity in an industrial-type space in Calenzano (Florence). His interest in artistic activity manifested itself since his adolescence, devoting himself mainly to drawing and painting. It was not until the late 1980s that he began to engage with continuity, directing his research mainly in the field of sculpture and installation. Between the late 1980s and early 1990s he was also part of a number of cultural associations, stimulated by the comparison of the various artistic researches that were being elaborated in them. His first exhibition was in 1989, after which he participated in numerous other exhibitions, both solo and group, in Italy and abroad. In this conversation, Andrea Marini tells us about his art.

GL. Childhood often plays an important role in defining what is the imagination of those who later decide to embark on the path of art, was this the case for you as well?

AM. The experience of my childhood was certainly crucial for me; I was lucky enough to be able to take advantage of a large space adjacent to my backyard where there was a long abandoned construction site. In this place there was everything: tiles, bricks, roof tiles, sand, pieces of wood and an area with a not inconsiderable amount of clay. In this space, during summer vacations, I would gather with a group of friends to play. It was for me a real gym used for creativity. We would model everything there, it was a competition to see who could produce the most surprising and original objects, we would even build real villages on the sand piles using the many materials available. After a few years the construction site was reactivated, but by then we were all older and the “creative gymnasium” had already fulfilled its duty. Another darker and seemingly less positive aspect of my childhood and adolescence greatly affected the imagery of my adulthood: my tendency, at certain times, to close in on myself and isolate myself with moments of depression. I believe that the search for compensation and sublimation to the state of suffering, which I experienced at the time, may have been a strong motivation for creativity.

What was your first artistic love?

During high school art school, I had the opportunity not only to study but to see Michelangelo’s works live at the Accademia Museum. Of course I was fascinated by his Prisoners, truly remarkable works especially for the so called “unfinished” that allows, looking at them, to complete the image with one’s imagination. But the work that I can fully consider my first love is the Pieta Rondanini, also by Michelangelo, initially seen in photographs and only later in person in Milan. I do not want to make critical comments here on such a famous, important and above all modern work, but I do want to emphasize that through this work a different mechanism was triggered in me that allowed me to establish, with the works of art that most involved me, a relationship of empathy that allowed me to overcome a purely scholastic approach to reach, instead, a more intense and complete understanding that approaches the emotional rather than the cognitive. And it is with this predisposition that I still approach works of art to grasp their true essence.

What studies have you done?

I attended art high school and the Faculty of Architecture. Despite my degree in Architecture, I preferred to follow the path of teaching, which allowed me to do work that interested me and at the same time have free time to devote to my artistic activity.

Were there any important encounters in your formative years?

During my training I was not fortunate enough to associate with prominent personalities in the artistic field, there were, however, people who were very influential in stimulating in me the potential needed to undertake and develop artistic activity. The first person goes back to my childhood; in fact, when I used to go play in the construction site-space, the older brother of one of my friends who was attending art high school, would sometimes sneak into our construction and provide us with valuable insights and original solutions. He certainly was a role model for me, perhaps my first real teacher. Another person who was influential in my education was the “figure” assistant in high school. He was a person who knew how to converse with students in a simple and unobtrusive way, thus managing to break the sense of mistrust that normally exists between teacher and pupil. By the end of high school, a friendship had almost been born between us that allowed me to get to know him better and, by visiting his studio, deepen my knowledge of his artistic production. At that time he was painting pictures where he often inserted wooden elements with three-dimensional effects that, I must say, influenced me greatly in my first experiments. The positive atmosphere in high school and especially the sincere and fruitful friendship relationship with classmates helped me to dilute my strongly introverted character and give rise to extremely stimulating moments of collaboration and creative confrontation both during and after school.

How has your work evolved over time?

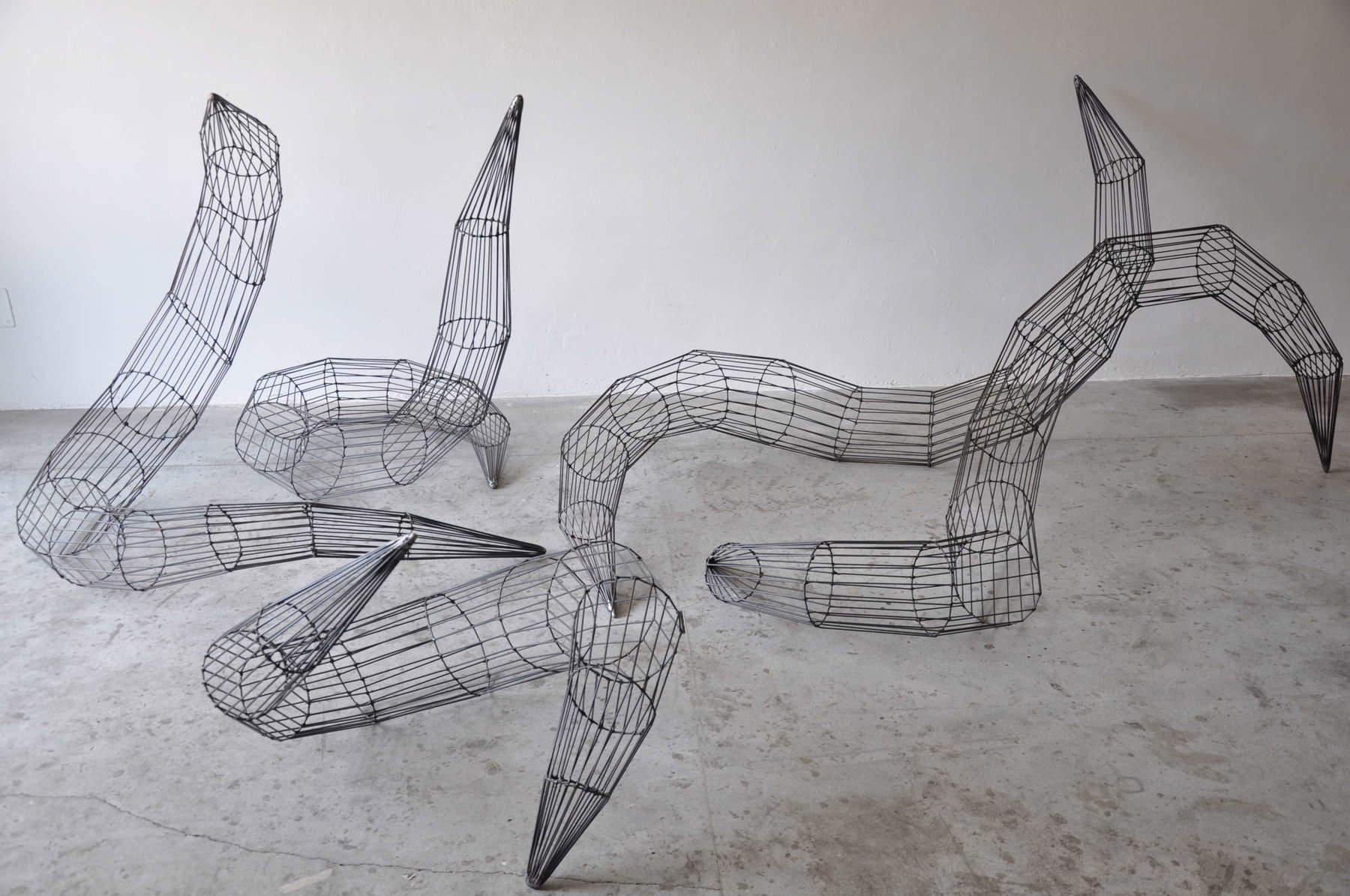

From about 1987 to 1992 I developed a geometric type of research and devoted myself to building structures, which I liked to call “sensitive architectures” because of their dialogue with inner phenomena and dynamics. For this kind of research, which was quite rigorous, I almost always developed very precise and detailed design-type drawings that allowed me to calculate the right dimensional relationship of forms and the balance of materials. Later, when I started a more organic type of research, I abandoned an overly analytical approach, now I only make quick sketches that serve to stop the idea of what I want to achieve and simultaneously verify its validity. I let the material and the construction itself, in its making, resolve the work and infuse it with vitality.

What are the substantial differences you identify between what you do now and what you did years ago?

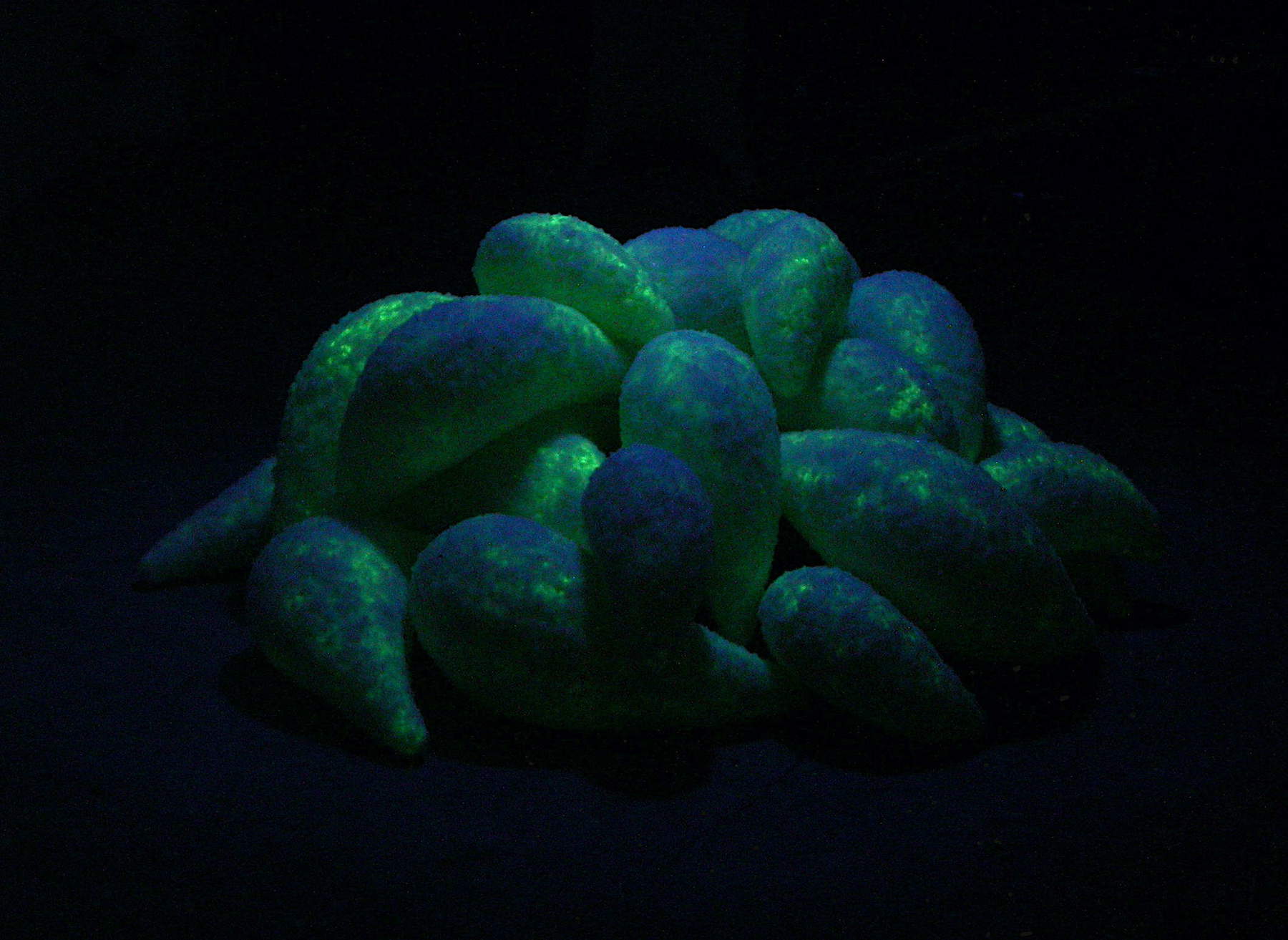

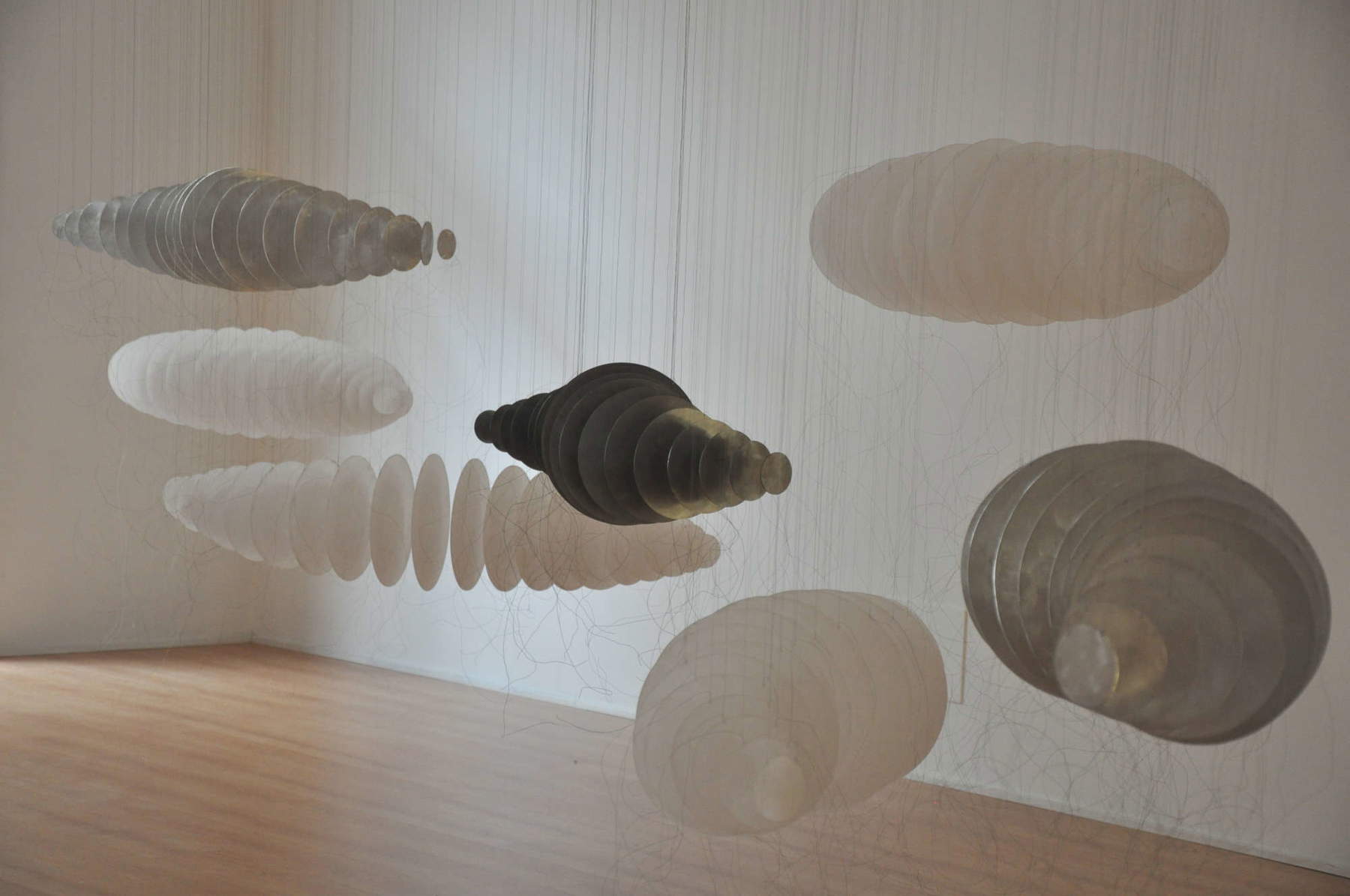

Granted, when I think of artistic activity in general and my artistic career in particular, I cannot help but associate it with a kind of tree, where the trunk represents the main flow that continuously goes to feed the desire for creation. The stream represents the totality of knowledge, experiences, stimuli and perceptions both inner and from the outside world: this constitutes the creative humus of my individual artist. The branches represent the various aspects of research that vary according to the intensity of the path taken and the time taken to develop it. Creation is thus for me, a complex interactive organism subject to transformation and change in a process of continuous osmosis between inner phenomena and external events. From this perspective, although it is difficult for me to clearly identify the deviations that have occurred in my artistic journey, I can say that an important change in my research began in the early 1990s. In fact, while I was developing a geometric type of research, as I have already said quite rigorous in itself, I felt a bit caged, constrained. Therefore, at a certain moment, I felt the need to tackle a more organic work that would grant me more creative freedom and also allow me to address, more directly, the theme that is still particularly close to my heart: to create or rather re-create a kind of unnatural naturalness, symptomatic and consequential of the controversial man-nature relationship that we are living. It is inevitable, therefore, that having to deal with the elaboration of a “new universe,” which in my research involves both the plant and the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic worlds, I have felt, over time, the need to experiment with as many forms and materials as possible in order to investigate and recreate in a personal and comprehensive way such a fascinating and complex landscape.

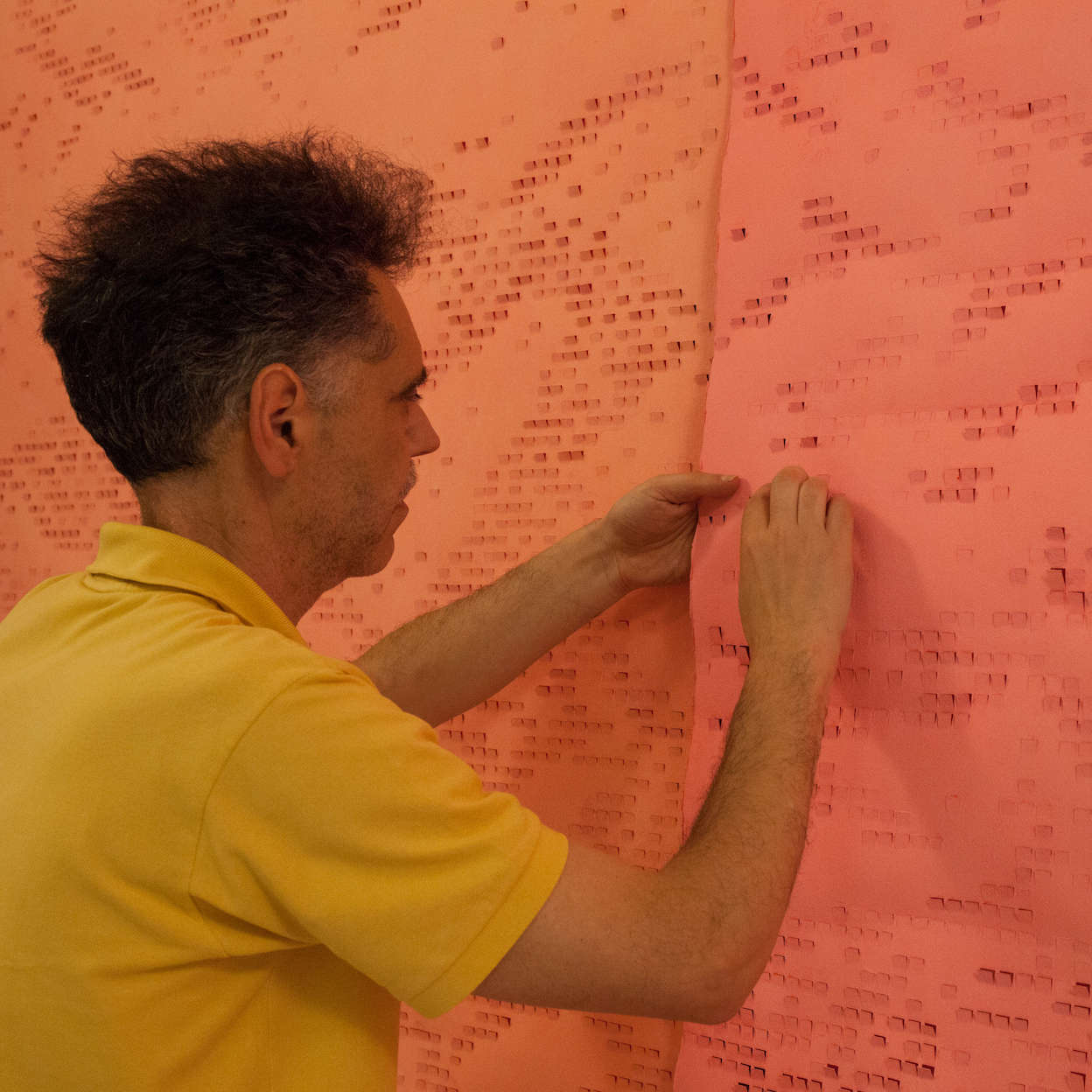

How important are the materials you employ in your work?

Clearly the choice of a given material has its importance, it is normally consequent to the type of work I have in mind, I try to make a work with the most suitable material to construct it. The material sometimes allows me to resolve the construction of the work as it is made: that is, I start from an idea of form that is only structured as I build it. Sometimes, however, the reverse can also happen, that is, it is the discovery of a new material that suggests to me the work to be done. In some specific cases, I use various types of material starting from objects, abandoned finds that have intrigued me giving them new life, I do not consider this a recycling operation but a “revitalization” of dead objects.

What is your idea of time and space?

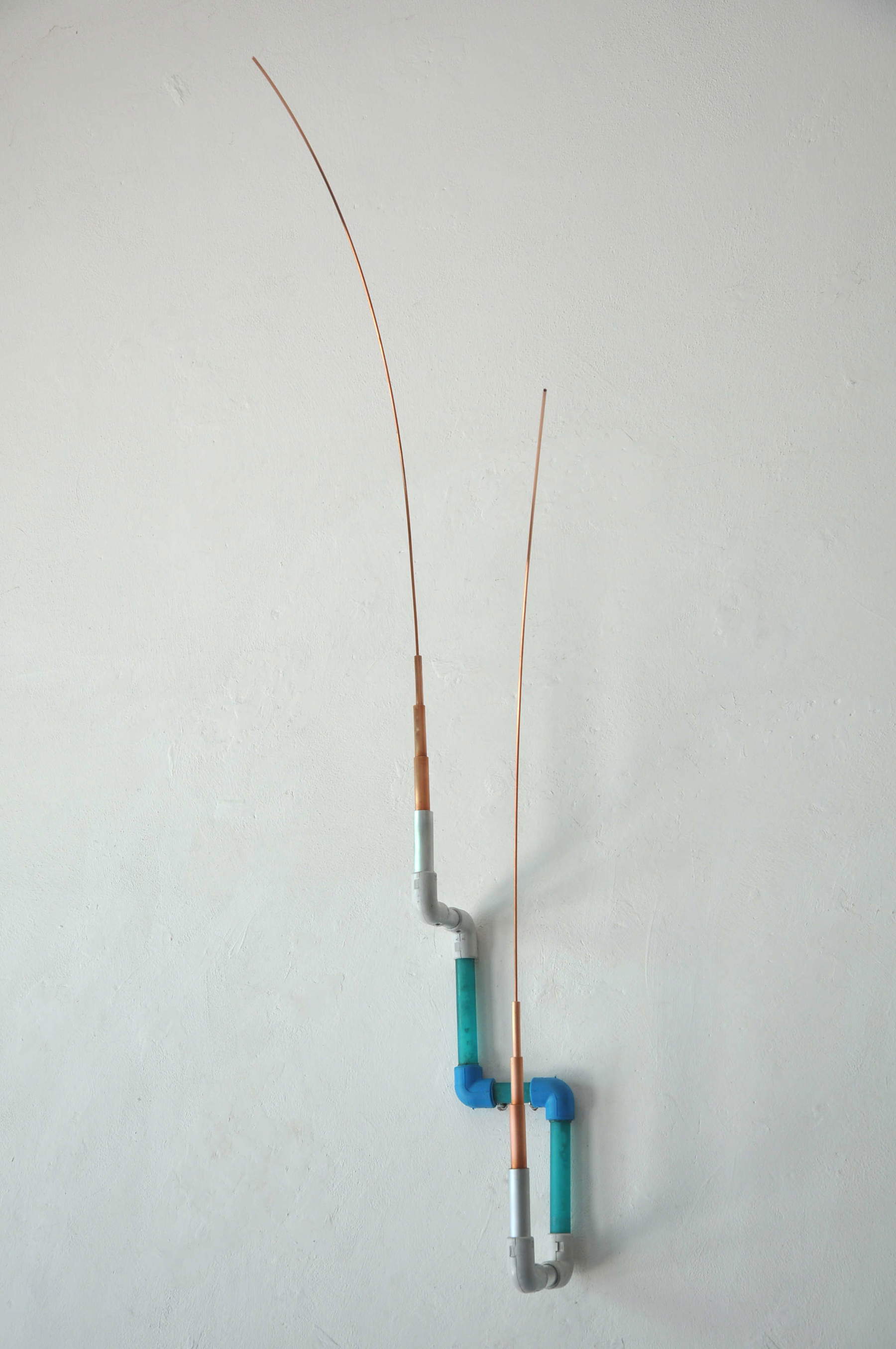

Maybe it’s age, but I often think about time passing. I perceive it as something tangible, almost visible, perhaps a rustling or even a flowing fluid. Surely time is something mysterious and at least ours, the physiological one, lengthens and shortens to according to situations. During sleep then, time seems to annihilate. We also know, according to the theory of relativity, that time slows down to the speed of light; emblematic in this regard is the famous movie Planet of the Apes. In making sculpture, I need time: first of all time to reflect, to focus on an idea, to figure out whether to make it concrete, to choose the most suitable construction method to make it, to identify suitable materials, and finally to start building. There are faster jobs, others slower, and because I often start several jobs I never know how long it took me to accomplish them. In the end the thing that interests me is that the result is a “timeless” work, something that can simultaneously belong to the past or to a hypothetical future. Space is definitely an extremely versatile entity that can be subject to many definitions and interpretations, certainly it is everything that can be included between the infinitely small and the infinitely large. Working in the field of sculpture, I am interested in considering a physically perceptible and commensurable space. Sculpture can enclose a space, develop in space, invade space.

What is your idea of nature?

It has been a long time now that because of the phenomenon of anthropization, with the continuous and multiple negative stresses from man, nature is under a state of stress. I experience it as a suffering nature that is losing its balance and reacting, as we see almost daily, violently causing disastrous consequences to man himself. In my reinterpretation of nature, I propose an “unnatural naturalness” or a new “naturalness” that, although suffering, seeks to restructure itself and live in a new world suspended between the real and the imaginary. Thus, I want to leave room for the hope of a “rebirth” and the possibility that a renewed balance can be achieved.

Are you interested in the idea of staging your sculptures when you exhibit them?

I think that any work contains within it an “aura” that exists regardless of its location and, of course, the more “successful” the work the stronger this aura will be. So in theory, absurdly, a “strong” work would not need any staging. In reality, any work in order to be valued needs proper placement, its staging not so much as a theatrical fact but as a search for the establishment of those conditions that will enhance the peculiarities of a work and enable the viewer to read and perceive it in its true essence.

What is your idea of beauty?

In a work of art, the sense of beauty arises from the many elements that constitute the work itself, and most of the time these elements are not well identifiable and codifiable. Each person interprets a work according to his or her own sensitivity, culture and contingent inner readiness to receive a message. Personally, I think that when confronted with a work of art, an idea of beauty can arise simply from an emotion, a subtle disturbance, a slight disquiet.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.