"Art is not just craft: it is also reflection and introspection." Conversation with Gianluca Sgherri

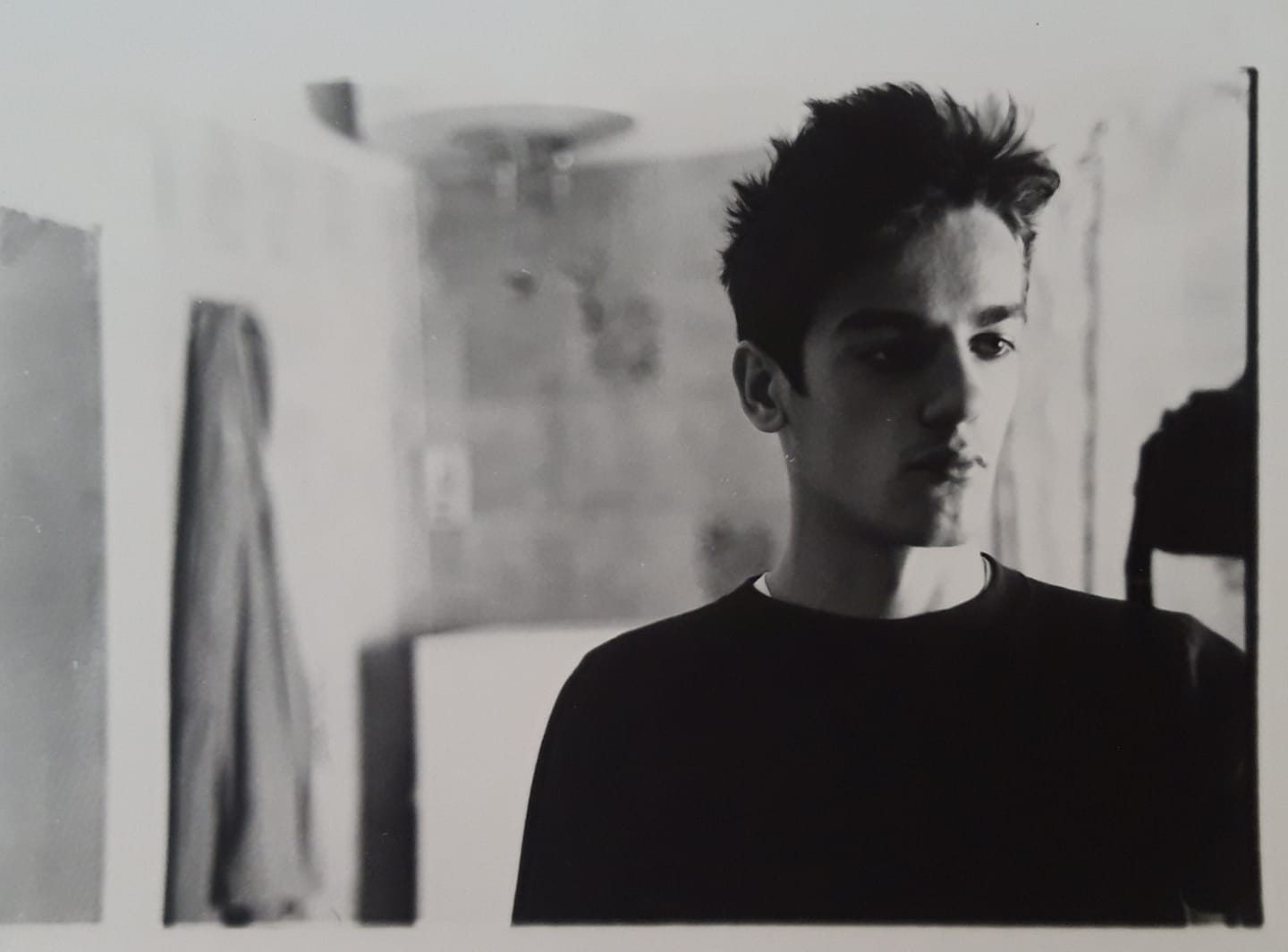

Painting as narrative but also as intimacy, direct expression and at the same time introspection. Gianluca Sgherri’s research is one of the most refined on the contemporary Italian scene. Born in Fucecchio in 1962, Sgherri, after attending art high school in Florence, graduated in Painting in 1986 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence under the guidance of Fernando Farulli. Following some graphic and musical experiences, he began his artistic career with the Marsilio Margiacchi Gallery in Arezzo, presenting his first solo exhibition in 1990. Together with the artists Federico Fusi, Luca Pancrazzi and Andrea Santarlasci and the art critic Maria Luisa Frisa, they give life to numerous exhibitions in Tuscany and other parts of Italy. Over the years, he has worked with Studio d’Arte Cannaviello, where he has been the protagonist of several group exhibitions with Marco Cingolani, Daniele Galliano and Pierluigi Pusole (and where he has held several solo shows), and he has also worked with Gallerie In Arco in Turin, at Fabio Sargentini’s Associazione Culturale l’Attico in Rome, and at Lucio Dalla’s No Code Gallery in Bologna. Sgherri also counts a participation in the Quadriennale in Rome as well as several participations in exhibitions in museums in Italy and abroad. Some of his works are in public collections such as those of Gamec in Bergamo and that of the Chamber of Deputies at Montecitorio in Rome. He currently lives and works in Santa Croce sull’Arno (Pisa). In this conversation with Gabriele Landi, Gianluca Sgherri talks about his artistic journey.

GL. Bruno Munari used to say, “A creative child is a happy child!” Did the experiences you had in your childhood have any impact on your work as an artist?

GS. Yes, but I don’t know if they influenced more the positive or negative experiences. In first grade, the teacher used to tie my left hand so that I could write with my right hand. From Monday to Friday I was the last one in the class, but on Saturdays in drawing hours I would get compliments, the girls would go around me, and I could sit in the front row. I grew up with the myth of Leonardo and Raphael. I used to copy their portraits from volumes in the regions, I was attracted to the trademarks that bore their names on pencil boxes, albums and books. I passionately followed the scripts on TV, imitated them and played with them. I was also a creative child, but mostly a dreamer; therefore, my happiness smelled of blissful loneliness. I was often and willingly “absent” from class, family or friends. I felt an irresistible need to estrange myself, that’s why I seemed a bit of an odd kid Everything is reflected in an artist’s work, for better or worse. Art has been a help to me and a reason for revenge, but also a way to keep dreaming...

Did your “super heroes” Leonardo and Raphael continue to accompany you even after elementary school?

I have a special relationship with Leonardo, however, the excitement I felt as a child, that feeling of closeness and identification, is of course no longer there.

Did you attend art high school? Who were your teachers and fellow students?

The choice of the Liceo Artistico in Florence was as forced as it was desired. After middle school, which was lived in a similarly unexciting way, arriving at an Art school where I could express myself at my best was a kind of liberation. In the classrooms I met Luca Pancrazzi and among the teachers I would like to mention the best known, Giovanni Ragusa and especially Renato Ranaldi. Those high school years were the best years. I would get up early in the morning to catch the train, the night before I would carefully prepare my toolbox for painting and I couldn’t wait for the day to come.

After high school you attended the Academy, also in Florence. I gather from the previous answer that of the Academy you were disappointed.

That of the Accademia was a painful and in some ways complicated period, for family and personal reasons, above all the death of my father. This (and not only this) led me to neglect my studies and attend little, devoting more and more time to friends, rock and the band I played in. Apart from this, the Florence Academy seemed to me a somewhat sad, backward and closed environment. Having no alternative, I enrolled in the painting course of Professor Farulli, brother of the better known violinist Piero and founder of the Fiesole School of Music. The professor always wore a black hat and a scarf around his neck and as soon as he came in he would go to the record player and put on Brahms’ Third Symphony. There were no great exchanges between us: I esteemed him as a person and artist, he gave me good grades, without reproaching me for absences and tardiness. A kind of disciplined freedom reigned in the classroom, some people drew the model, others were bohemians carving out a small studio, and still others followed and imitated the teacher. I, as I said, went and came back, was there and wasn’t there, and realized that the sense of novelty, awe and wonder that I felt in high school had vanished. Gone were the school trips, no one was running after the professor on the ancient pavements of Pompeii, in the churches and museums of Rome and Venice or on the lawns of the Reggia di Caserta, not even exams and quizzes were scary now: everything was planned and agreed upon. The spirit of class, solidarity and participation gave way to individualism, envy and personal ambition. Everyone felt like an artist.

During your Academy years, had your artistic research already taken a direction?

No, not even after that. It was two years after graduation when I went to Remo Salvadori in Milan. He had his studio on Via Tadino at that time; you could also see Mimmo Germanà’s studio from there. I brought him pictures of my work and he said (more or less): you are like a little bird in a room that beats all over the place and can’t find its way out...

In the meantime you continued your activity as a musician what kind of music did you make?

Let me preface this by saying that I am not a musician, I barely play the guitar and make a few notes on the keyboard, but this did not prevent me at that time from composing and writing songs... the 1980s were the years of Punk and New wave, two genres in some respects “easier” to play and within everyone’s reach, and this favored the birth of many more or less improvised bands. Without great technical and virtuosic skills, it was enough to put together two chords, a lot of grit and a bit of craziness; so were Alito Control, a Post-punk formation I was part of. We used to perform at Unity parties, alternative clubs and discos in the area. We were inspired by British bands like Joy Division, PIL and the Cure. We also recorded two pieces in the studio, which to hear them again are not bad at all.

In the years after the academy, you made experiments approaching Arte Povera: what works were they?

Very beautiful and evocative was the bed of crosses: a one-square wire mesh pierced by small wax crosses. Or the three wooden letters resting on the ground: the “d,” “i,” and “o” (God). The first one was exhibited in 1990, in the group exhibition “The Cells” in Fucecchio and the second one re-presented 30 years later at the Palace of Arts also in Fucecchio. Other works were destroyed due to lack of space, poorly preserved or dispersed. I still have the mold of the cross where I was pouring wax, some works in glass and marble, two white sculptures in wood and plaster. As you said, I was inspired by poor and conceptual art, I frequented galleries and artists working in that direction, and every month I bought magazines. I did not refrain from doing performances and works with writings, such as “profanity” with transferables.

Using Remo Salvadori’s metaphor, when is it that the bird finds the window and manages to leave the room?

When he realizes that we are in a big cage, that we can fly everywhere but there is no way out. So he created a smaller cage all to himself: he sat down at the table with a small easel and began to paint....

I remember that some time ago you showed me a small painting on a board in the color range of blues, painted briskly, which bore a red cursive script. If I remember correctly, the phrase ran across the painting horizontally and was a poetic phrase. In showing it to me, you told me that it was the first painting in which you had introduced writing. I also remember D I O at the exhibition in Fucecchio. From what you told me earlier I would say that letters have always been part of your universe: what attracts you to the dimension of writing?

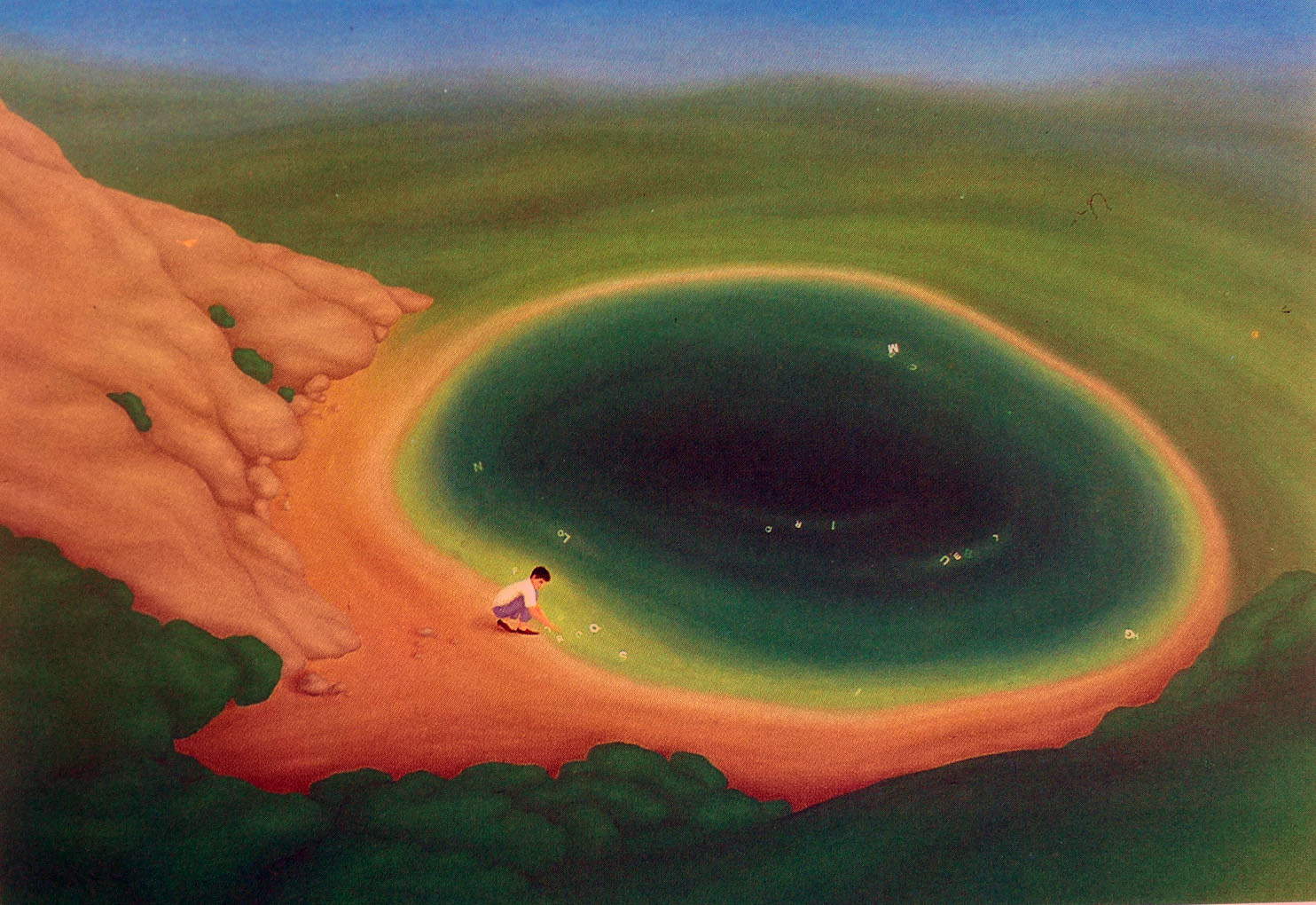

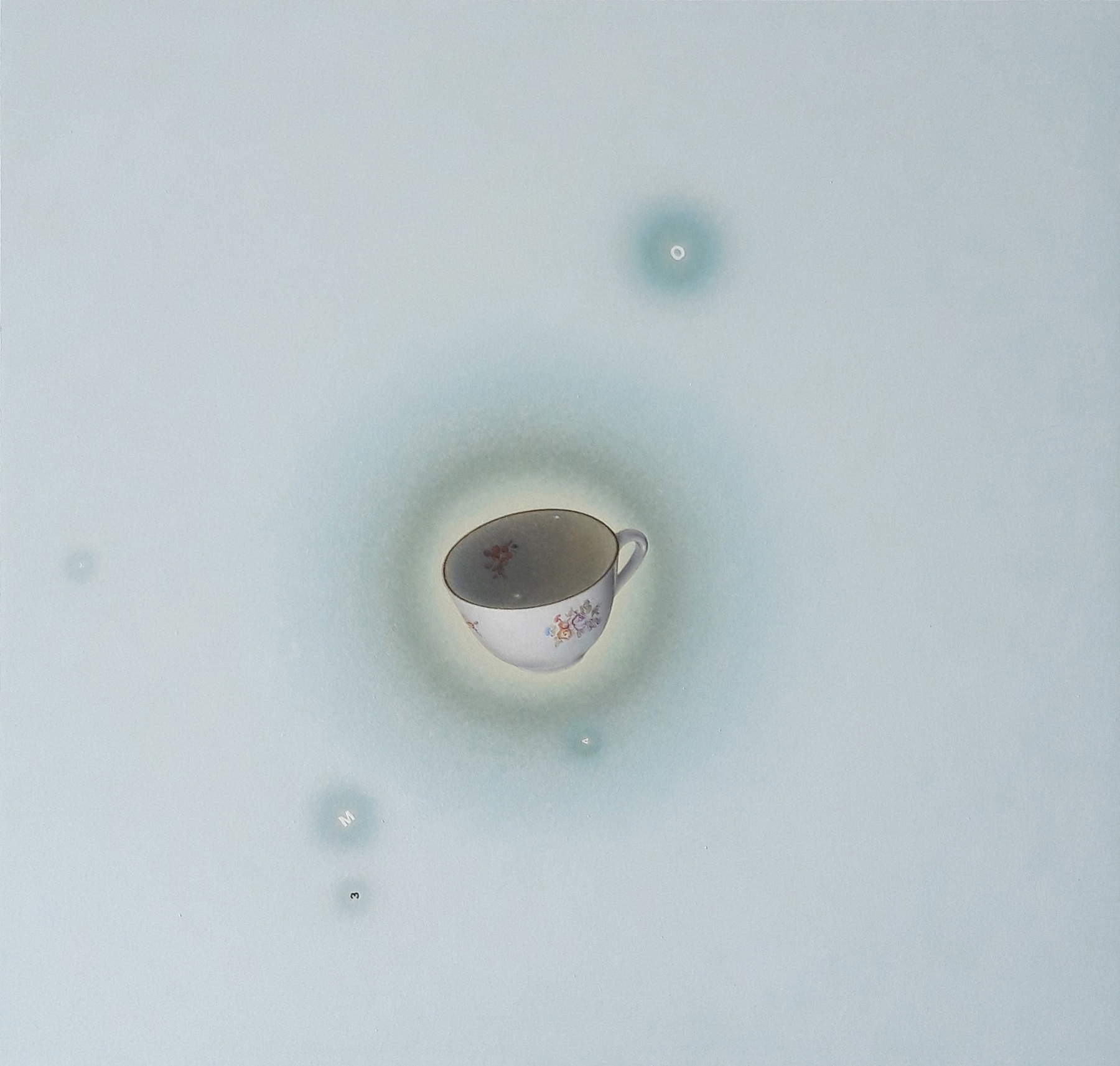

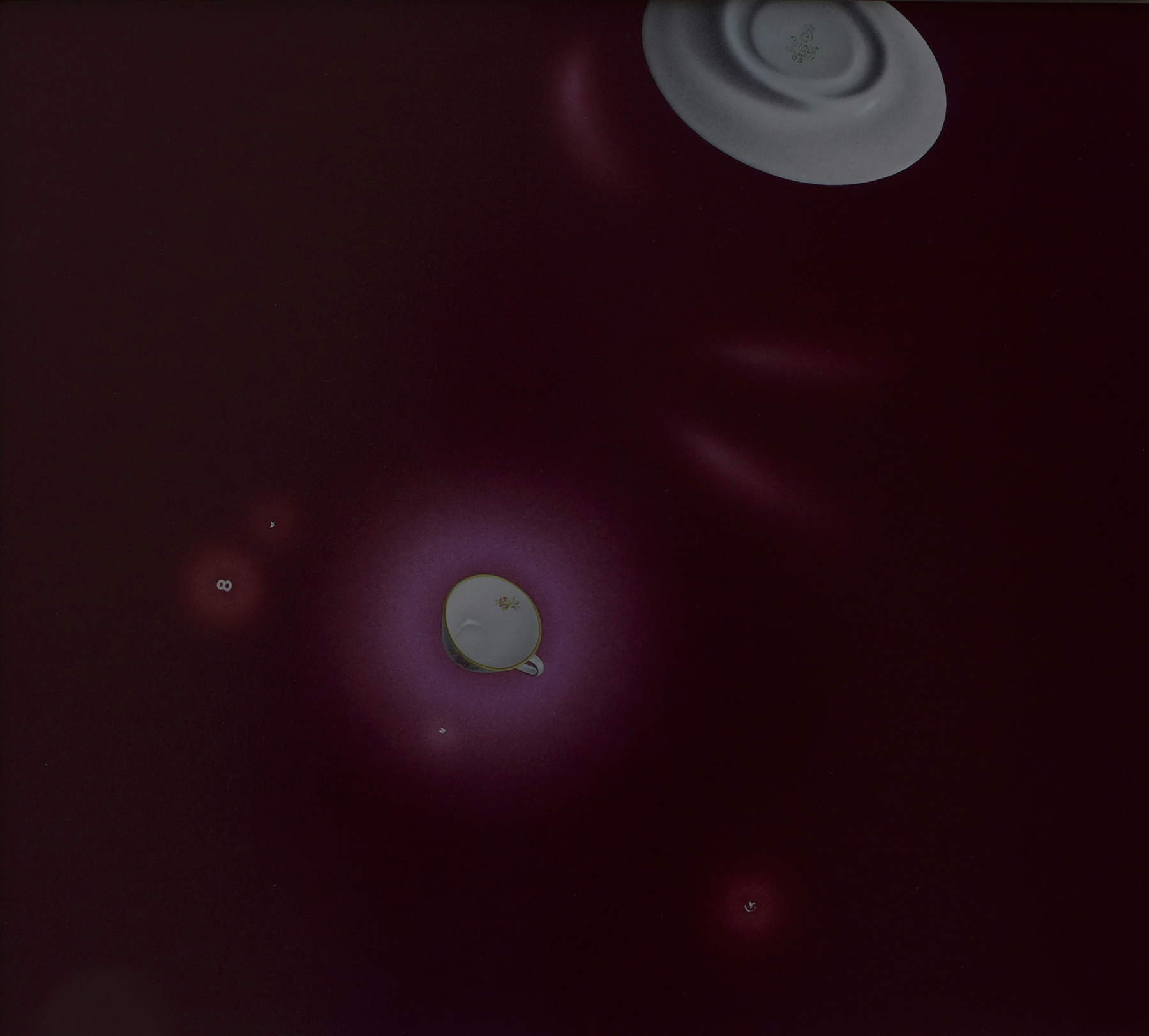

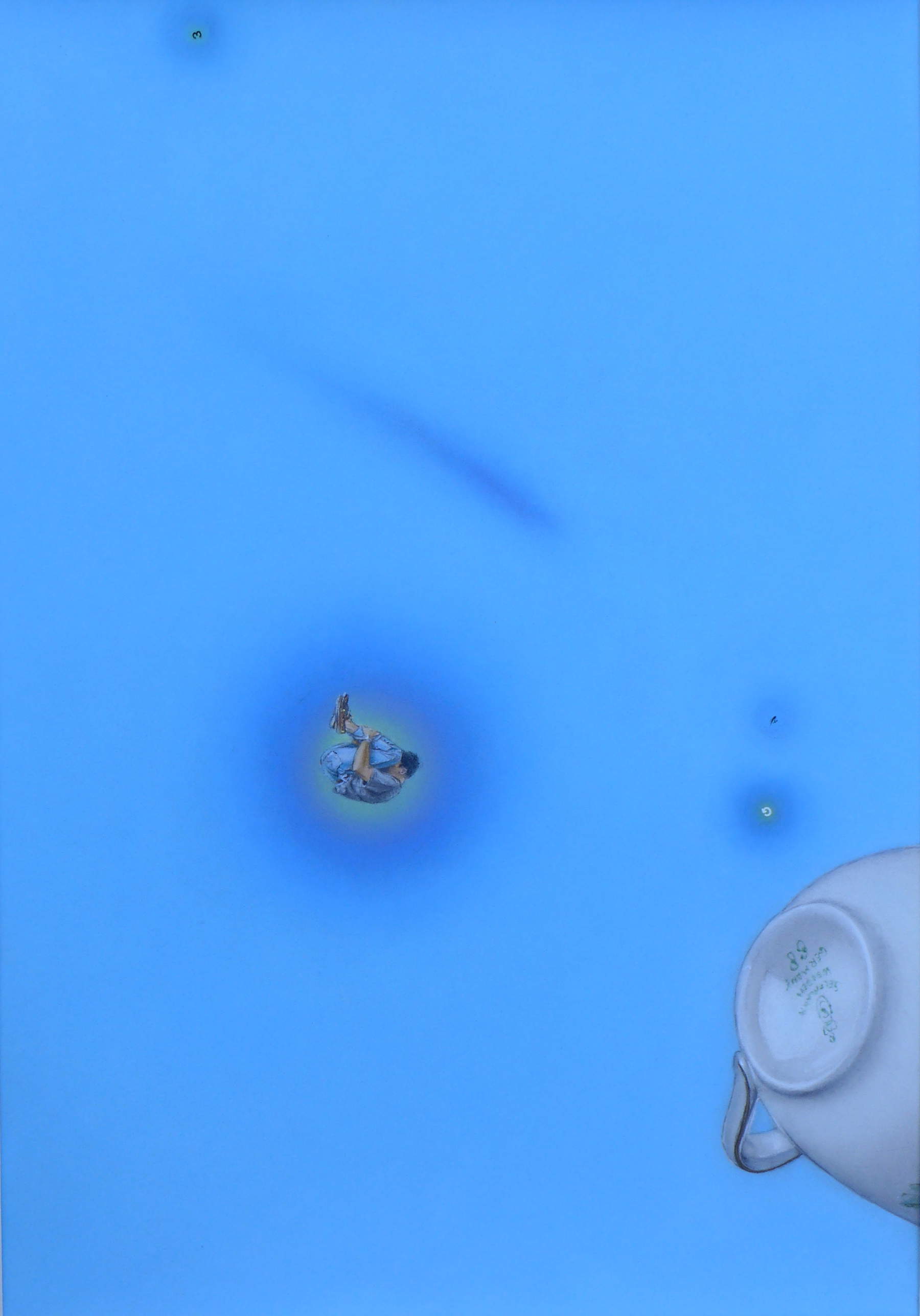

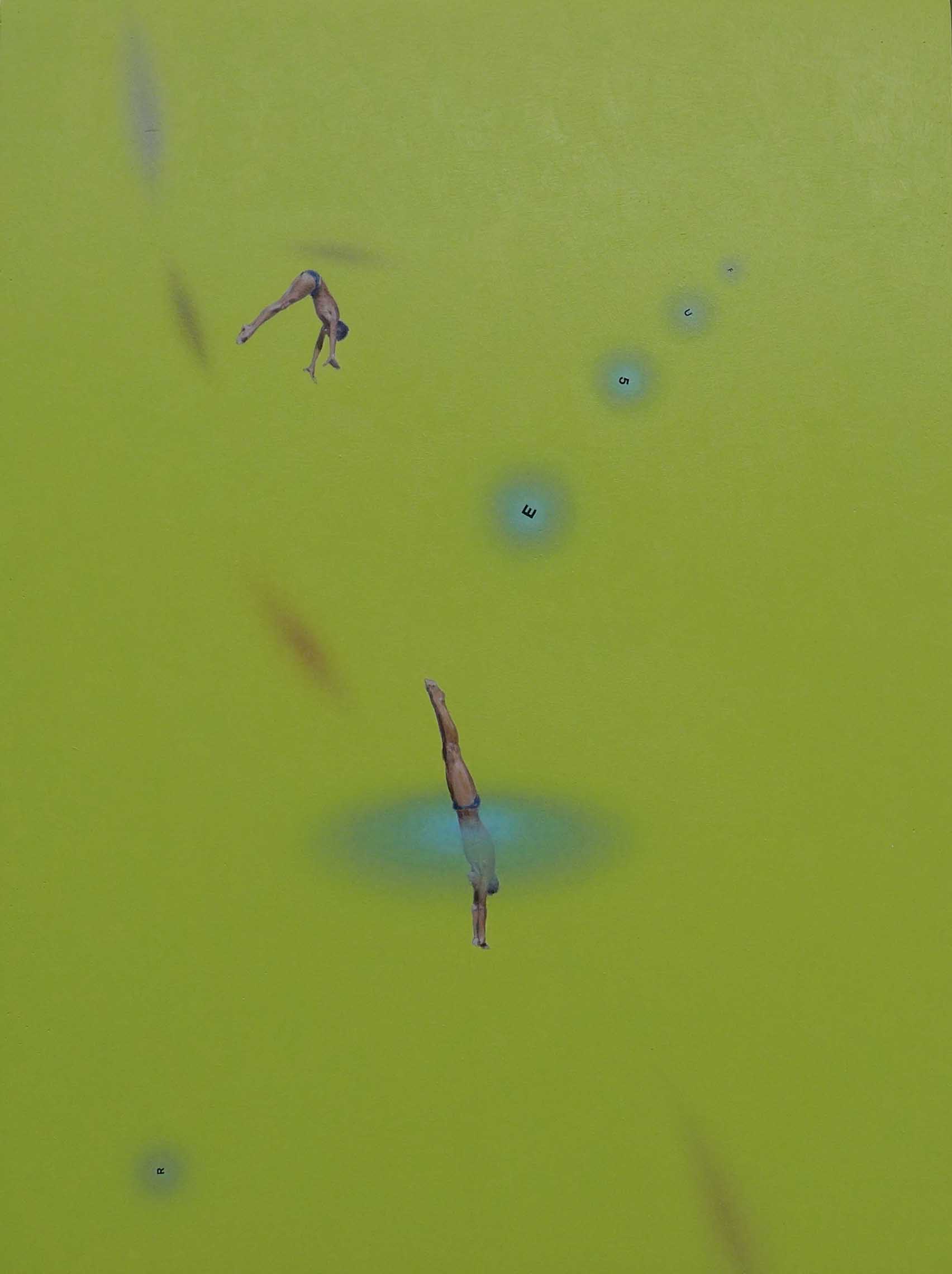

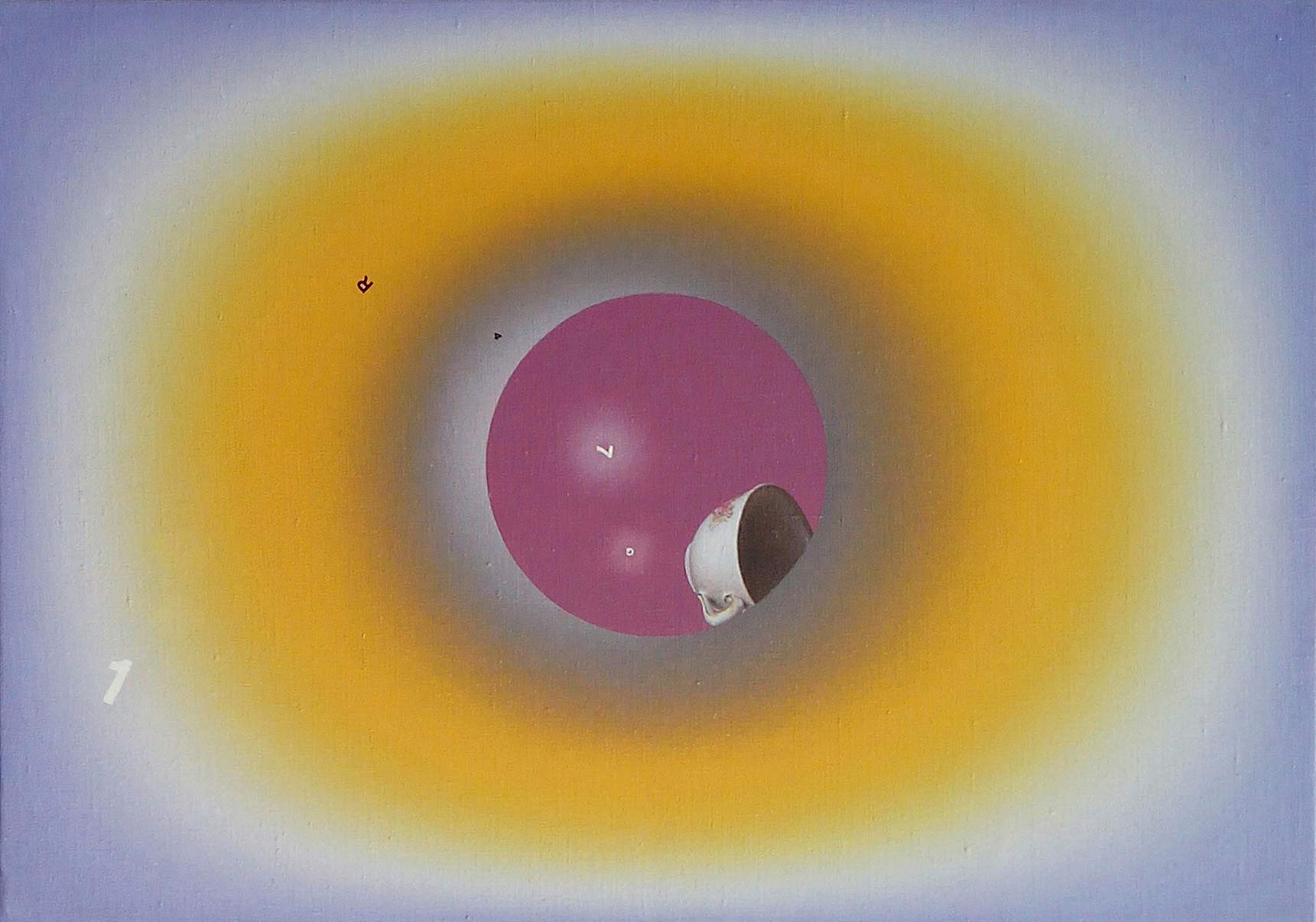

The direct, explicit, objective expression. When I started many artists used phrases, writing, titles; however, in most cases, especially in painting, certain works appeared forced and pretentious, like, “since I can’t do it with painting, I help myself with words.” When, on the other hand, the written and alphabetic form merges and becomes the idea itself, it becomes beautiful and interesting. In my case if, you will, the three letters of the installation “God” and the as many little letters that dot landscapes and cups, are part of and a function of the work. The little square with the phrase “skimming airily over the top of the earth” is a statement of intent, a wish, a wish, that in reviewing it makes one tender. It is one of the earliest paintings ever: its raw, primitive appearance may leave the viewer baffled and indifferent, yet it already contains all the potential and characteristics of my work.

Between the bars of the small cage, all to yourself, where you began to paint, what did you see?

I saw the small garden where pine, apricot, pear and plum trees reigned. In one corner was the tire and in the middle an armchair. In summer the pine, apricot and plum trees provided shade and bore fruit. The perimeter of the lawn surrounded by the little wall and the railing, was the same and matched the rectangle of the sky. The studio lying long on that ground was suspended between one and the other, between earth and sky. The freshly mowed green grass lapped the logs, the pots and the concrete....

What you describe sounds like a perfect world with a well-defined perimeter, where everything is under control. How does the space-time dimension behave in this place?

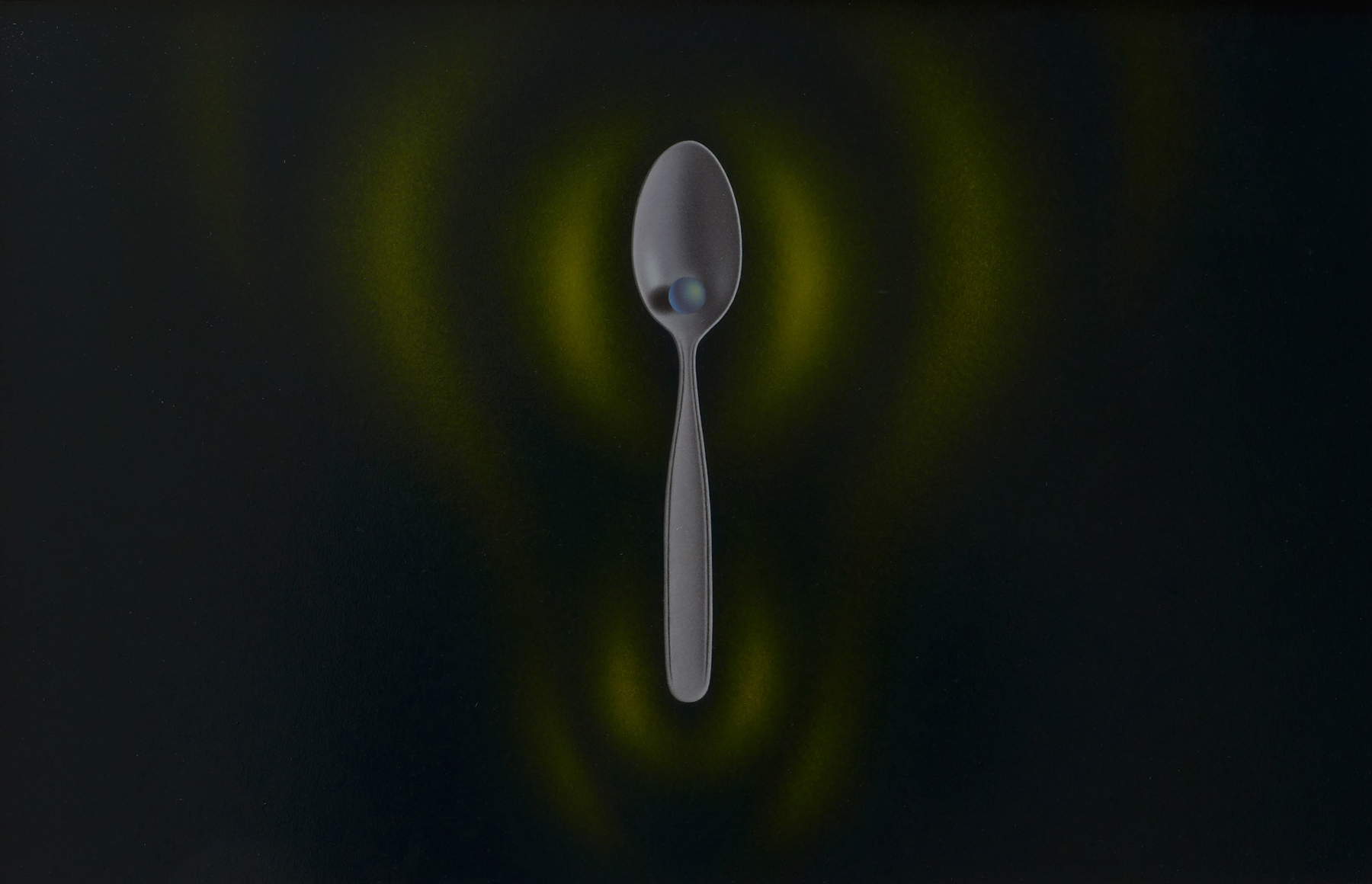

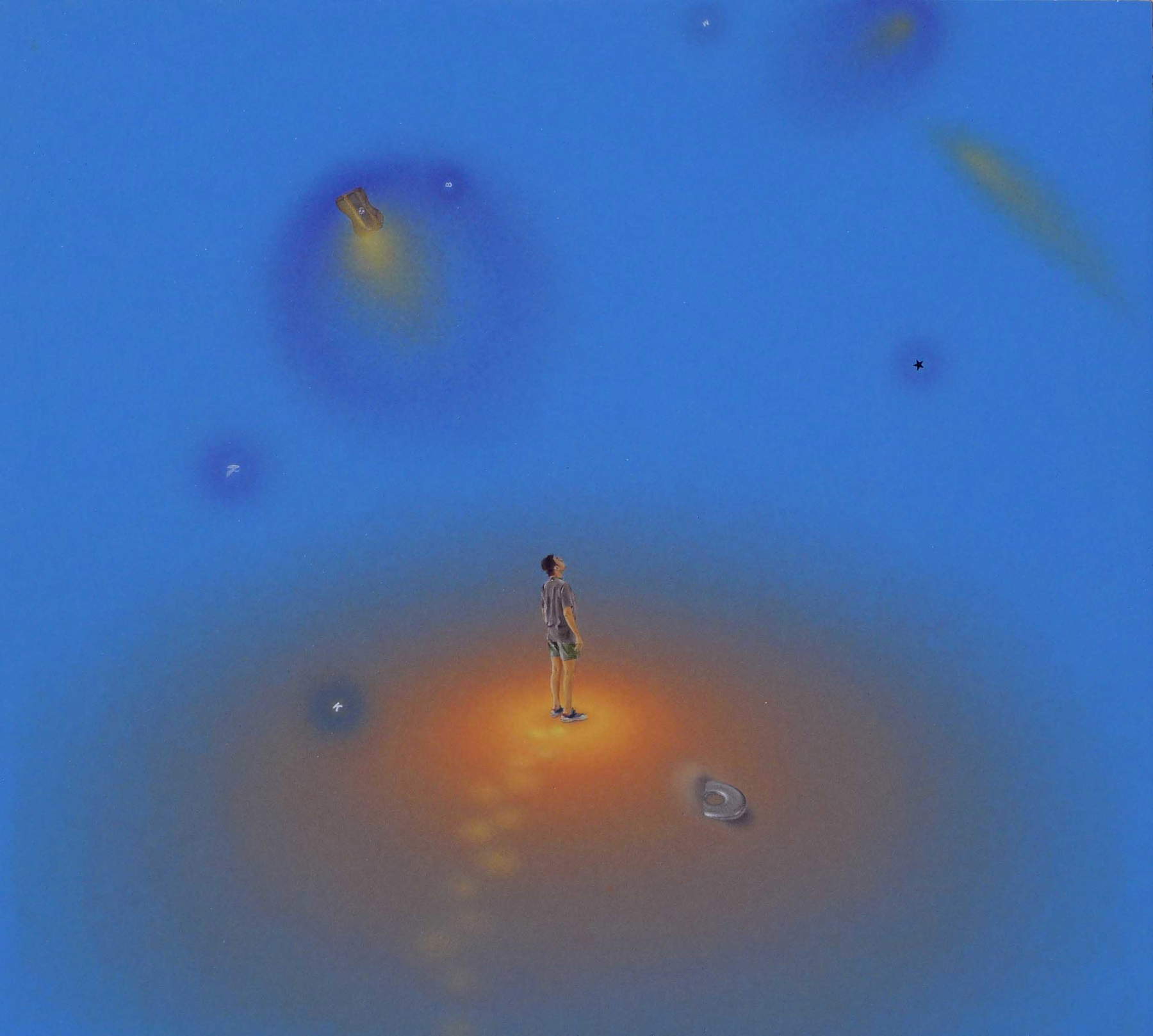

It is an intimate, circumscribed, orderly, still dimension, where everything is within reach: the cups, the garden, the pond, the little man, the armchair...

Everything you painted in your early 1990s paintings you saw in this space?

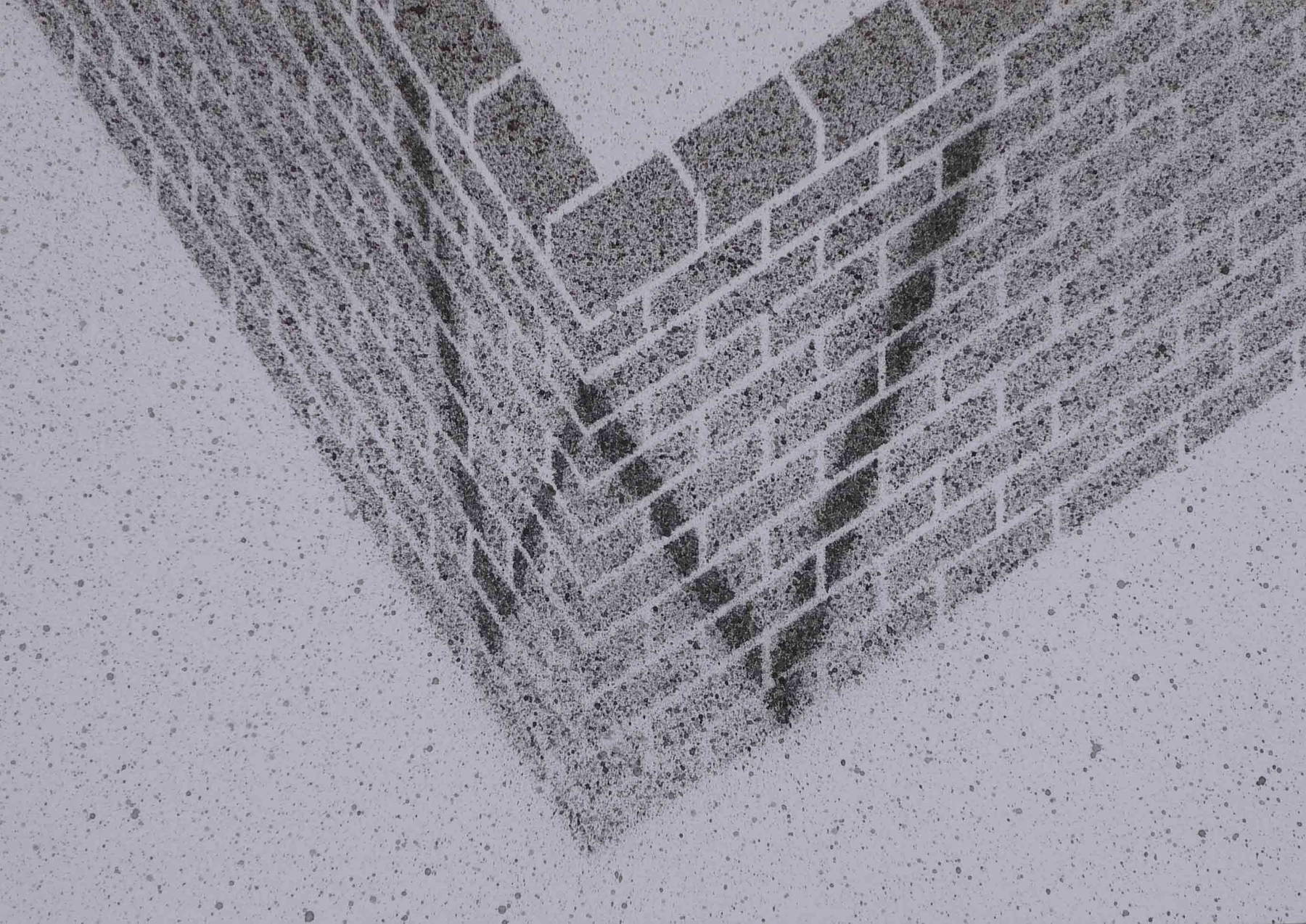

Yes, but not only that. When I first started going to Milan I was attracted to the city and architecture, in fact the works of the interlocking and axonometries were born ... which in turn referred back to the games of construction.

Maria Luisa Frisa, introducing your work in your first solo show, at Margiacchi’s, talks about your garden and your house as places to reverie: what role did boredom and idleness play in this process of reverie?

They pushed me to look around and to fantasize, precisely. Some key paintings were derived from this state of mind, such as the sleeping young man in the shade of the pine tree, the children climbing trees, or the boy sleeping inside a cave... Boredom and idleness are part of life, I do not believe in creative and productive twenty-four-hour rush, in constant effort at any cost; artistic creation is often preceded by periods of impatience and apathy. Art is not only craft, it is also reflection, introspection, making up for the lack of something. As a child I was often left alone, my father traveled by truck and my mother also had to work, so I made up for it with art and imagination: this is also how you can grow up and become an artist. Know: always make your child play and provide fun, and he will never be an artist! And maybe that’s even better! [Laughs]

Yeah, you’re right! In this world ofreverie, of what Bachelard would call Rêverie, often the atmosphere is nocturnal, there is a single character performing simple actions such as walking, sleeping, climbing trees, or stirring the waters of a lake or stream in which perhaps glowing letters float. Does all this imply a narrative, a form of storytelling?

The simple, normal, everyday actions you mentioned, when transferred from reality into painting take on a mystical character, one of serenity and bliss, like characters in a nativity scene. I remember a few in particular: a shepherd sleeping it off in front of Jesus’ hut, another smaller one lying on the grass watching the scene from afar. More than a story in narrative form, mine is a state of mind.

At the same time, objects such as paintbrushes, jugs, the famous cups also begin to appear... it seems to me that Ludovico Pratesi in the presentation of your solo exhibition at Fabio Sargentini’s Attico speaks of magical realism: do you recognize yourself in this definition?

I would not speak of magic realism, at least in the historical sense. My pictorial references at that time were Salvo and Lorenzo Bonechi.

Is there in your work in these years a desire to invent your own iconography?

Not really. I was more intent on building a lexicon, a pictorial vocabulary from which to draw whenever circumstances required it. I think the more poetic and narrative phase to which you refer is to be considered a parenthesis (albeit an important one) in my path: it belongs to an “age of innocence” that as such cannot last long and forever.

In this period also begins the exhibition activity in which the figure of Maria Luisa Frisa plays an important role. Can you tell how you came into contact with her?

Maria Luisa was the critic of reference for contemporary art in Tuscany, I used to read her articles and reviews in Flash Art. I managed to make an appointment with her, went to her house in Via dei Servi with some paintings under my arm, and from there began a fruitful and intense collaboration that gave birth to some of the most important exhibitions and catalog publications. Maria Luisa had interacted well with my work: she created space and gave breath to the writing....

Those years also saw the beginning of an intense exhibition activity initially within a group of artists involving, in addition to you, Andrea Santarlasci, Luca Pancrazzi and Federico Fusi, polarized around Marsilio Margiacchi’s gallery in Arezzo. Was there a dialogue between you, a common feeling, or was this meeting the result of a fortunate contingency?

We might have seemed like a close-knit group, in reality we often discussed and argued about what to do, how to move and where to go, and Marsilio made no small effort to keep us united. Having said that, I think nothing is born by chance, and if there were convergences and affinities in the work and ideas we see it now, after some time, as is often the case.

How did you get in touch with Marsilio Margiacchi and what were the important episodes that marked this collaboration?

Luca and I went on the recommendation of a friend; the gallery was in the center of town, behind the church of San Francesco, with the famous frescoes by Piero della Francesca. Marsilio liked our work very much and so it was that Arezzo became our second home.

The collaboration with Marsilio was short but very intense: from there many paths opened up. On Parola d’artista we have already talked about your meeting with Luciano Pistoi and your participation in Volpaia. What other avenues opened up at that time?

Many requests came from some of the most important galleries in Italy, but because I am a sentimental type, who gets attached, I let it go. I remember that a well-known Milanese gallery owner borrowed Ferrari from one of her collectors to visit us and propose a solo exhibition of mine. I was stunned when he said he was driving two hundred mph on the highway. He returned to Milan the same evening with only one invitation to dinner from Marsilio in his pocket. Everybody liked my work, though, it was incredible: the day before, a critic from New York called me to invite me to a group show, and the next day the electrician at home, by chance, wanted to buy me a square...

What convinced you to take the road to Milan?

There came a time when I couldn’t work, couldn’t go on; I was looking out the window of my studio with my head resting on the desk, like in elementary school ... a change was needed. I made the most logical and feasible decision: I told Cannaviello to look for an apartment for me to move to Milan. We went to look at a lot of houses, eventually subletting a studio apartment in a railing building, as it was more accessible and less expensive. It was located near Corso Lodi. At first we slept on an inflatable mattress, then we bought a sofa bed in the store below; it was heavy, and Klaus Mehrkens and I carried it up as the snow fell in flakes through the branches of the still bare, black trees on Via Lazzaro Papi. It was an area, that one, once of factories and smokestacks, as Boccioni painted them in the early twentieth century.. When we arrived, before it became a fashionable neighborhood, there were two bars on the street, complete with arcade and billiard halls. A few old stores survived, such as the ropemaker, the glassmaker and a small workshop where they made playing bowls. There was no shortage of the cobbler, regional restaurants, a take-out food stand, pharmacies, car dealerships, banks and barbershops-in short, it was all there. We lived between the room, the sidewalk, the double-crossing traffic light intersection and the market street, as in Bianciardi’s La vita agra. The first day I walked along the avenue, there were stores and bars from one side to the other, as the snow and fog melted in the sun. At the top of Corso Lodi people were hurrying down the subway stairs, above ground at Porta Romana the cars and streetcars formed a big carousel; everyone was honking their horns and bells..

When you arrived in Milan had you already exhibited there?

Yes, at Studio Corrado Levi with Pancrazzi and Santarlasci in ’91 and already at Cannaviello’s in the group show “Immagini di pittura” in ’93.

Enzo Cannaviello Gallery was best known for his work on artists from the German area devoted to expressionism. From him you could see large paintings painted with broad brushstrokes and very violent colors. How much further from your work. How did you come into contact with him?

When I met Cannaviello I had the impression that he wanted to change, to turn over a new leaf. He was looking for Italian artists who had something to do with painting, but with a more elegant and refined style, close to our tradition. I was happy and proud to be part of the Gallery but at the same time a little worried about the differences you say.... At Cannaviello’s I felt like Pinocchio at Mangiafuoco’s house; that is to say, in the hands of a strong, powerful gentleman with a sentimental and generous character accustomed, however, to dealing with and chewing other material. Enzo came to see me at the studio in Santa Croce on the instructions and advice of Maria Luisa Frisa; he arrived driving a Mercedes-Benz with his wife. Even before we said goodbye, he handed me a stack of catalogs from the trunk of the sedan; they had direct, simple and Spartan graphics; they bore the names of Anzinger, Baselitz, Clement, Disler, Fetting, Middendorf, Nitsch, Paladino, Penck...

Since you mentioned the character I would like to ask you to talk about Corrado Levi, an attentive collector, active as early as the 1950s, endowed with a super eye capable of seeing far ahead, who between the late 1980s and early 1990s launched many artists on the scene...

We knew him mostly as an artist, in fact when we did the exhibition we hardly ever saw him. I last attended a performance exhibition of his in 2000, which frankly I didn’t understand. The day we showed up at his house me, Luca and Andrea was very kind and welcoming, I gave him a little square however I regretted it.

When you arrived in Milan did you have a studio?

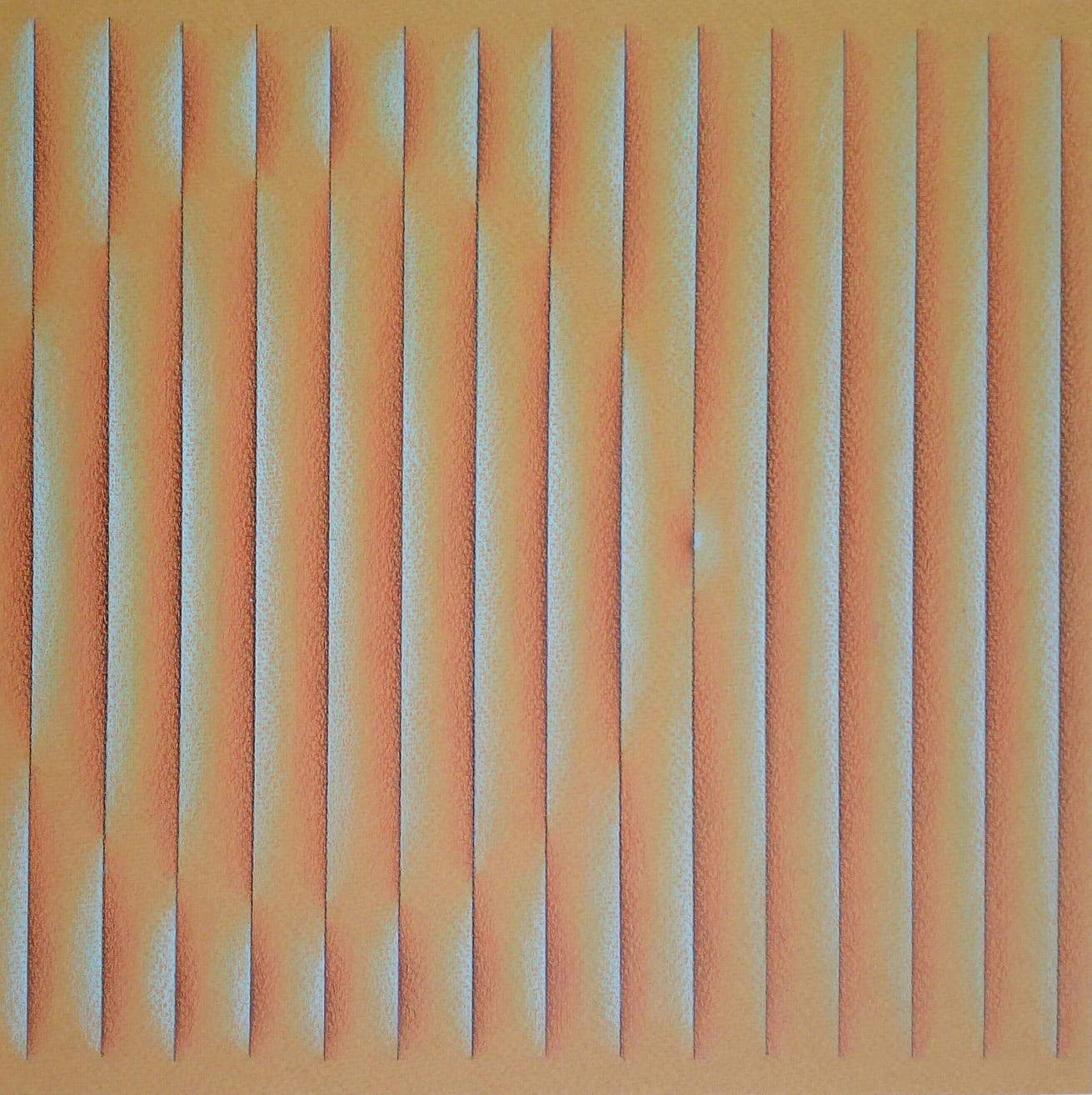

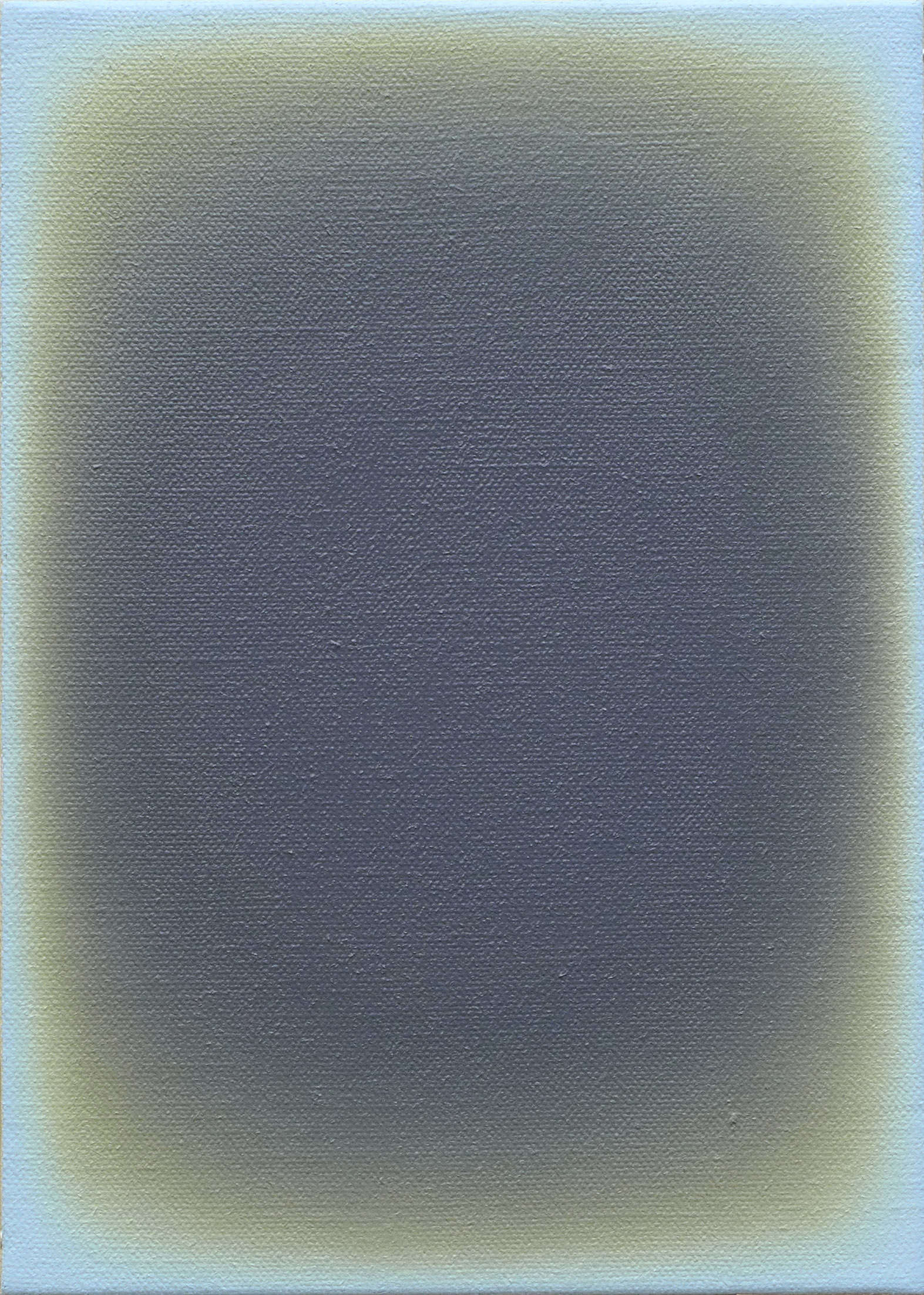

At first I shared a studio with a contemporary art restorer who knew Cannaviello. She was half crazy however she got it right. She once told me that nuance is my bread and butter and so it was. The studio was located on Via Olmetto, one of the old streets around Via Torino. In the early days I would ride the subway to work, as if I were a clerk in the downtown offices. After a few months cohabitation became difficult, and when we found another apartment I equipped myself to work at home.

Your work especially in those years was concentrated in small sizes. To what do you owe this choice?

The choice of small formats came from a need for intimacy, recollection and perhaps “normality”....

In this choice is there not also a desire to take a clear stance against the transavantgarde generation that favored large formats?

No position, however, it is clear that we were at the antipodes.

You were also at antipodes in the way you understood painting, they made it a matter of reaction to an earlier climate, whereas in the case of the artists of your generation I think this opposition was never experienced as a problem!

Exactly.

Your work over time has changed, you have gone through different seasons, while always remaining faithful to painting: what binds you to this practice that everyone punctually gives up for dead and instead always surprisingly rises from its ashes?

Periodically people say “painting is dead,” “painting is resurrected,” “now painting is no longer going,” “now painting is fashionable...” In fact, painting is always present, everywhere, from its origins to today it never ceases to exist. Even the artist who does not paint at all, rejects it or disowns it comes to terms with it and confronts painting. For my part, I am bound to this practice by something primordial and original....

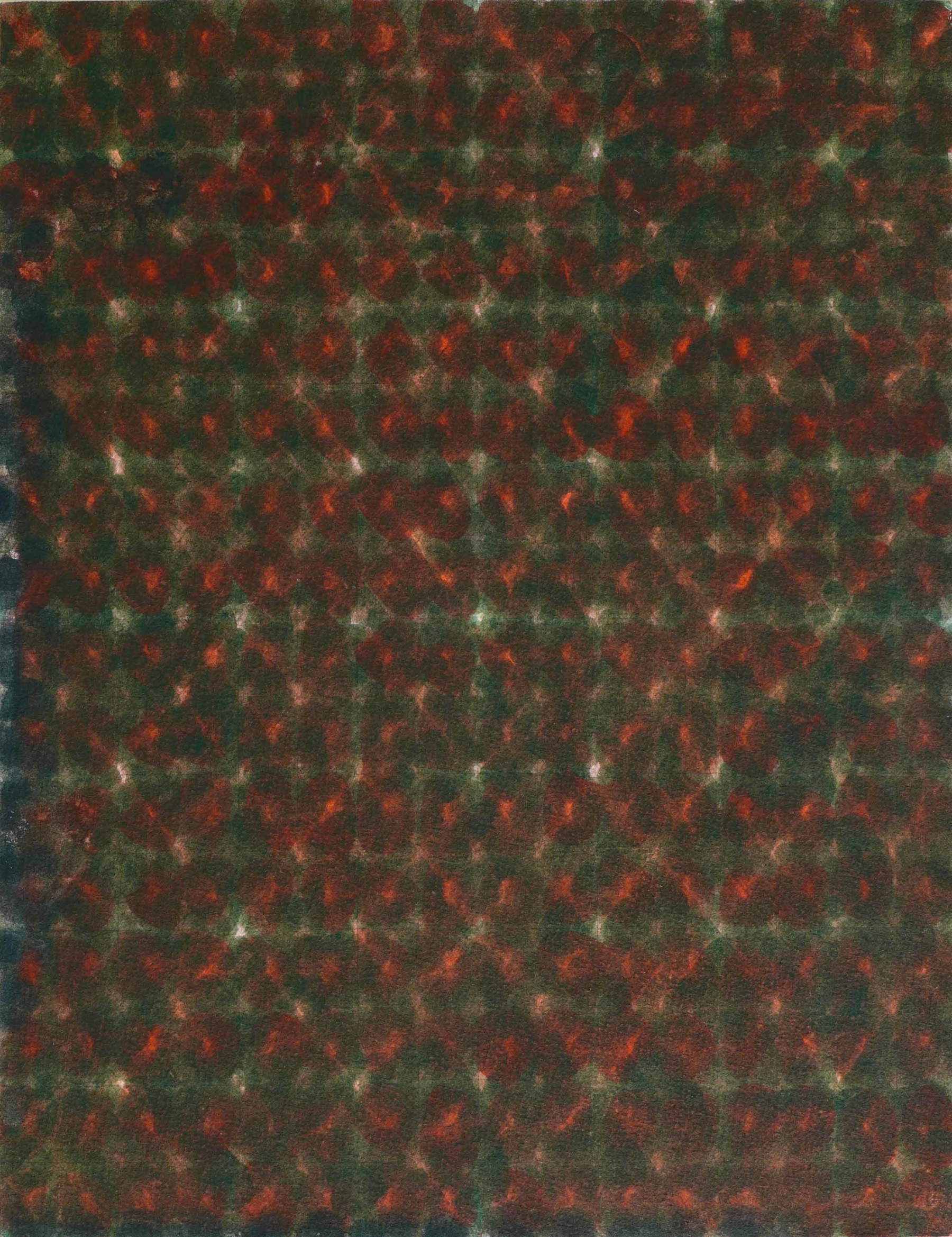

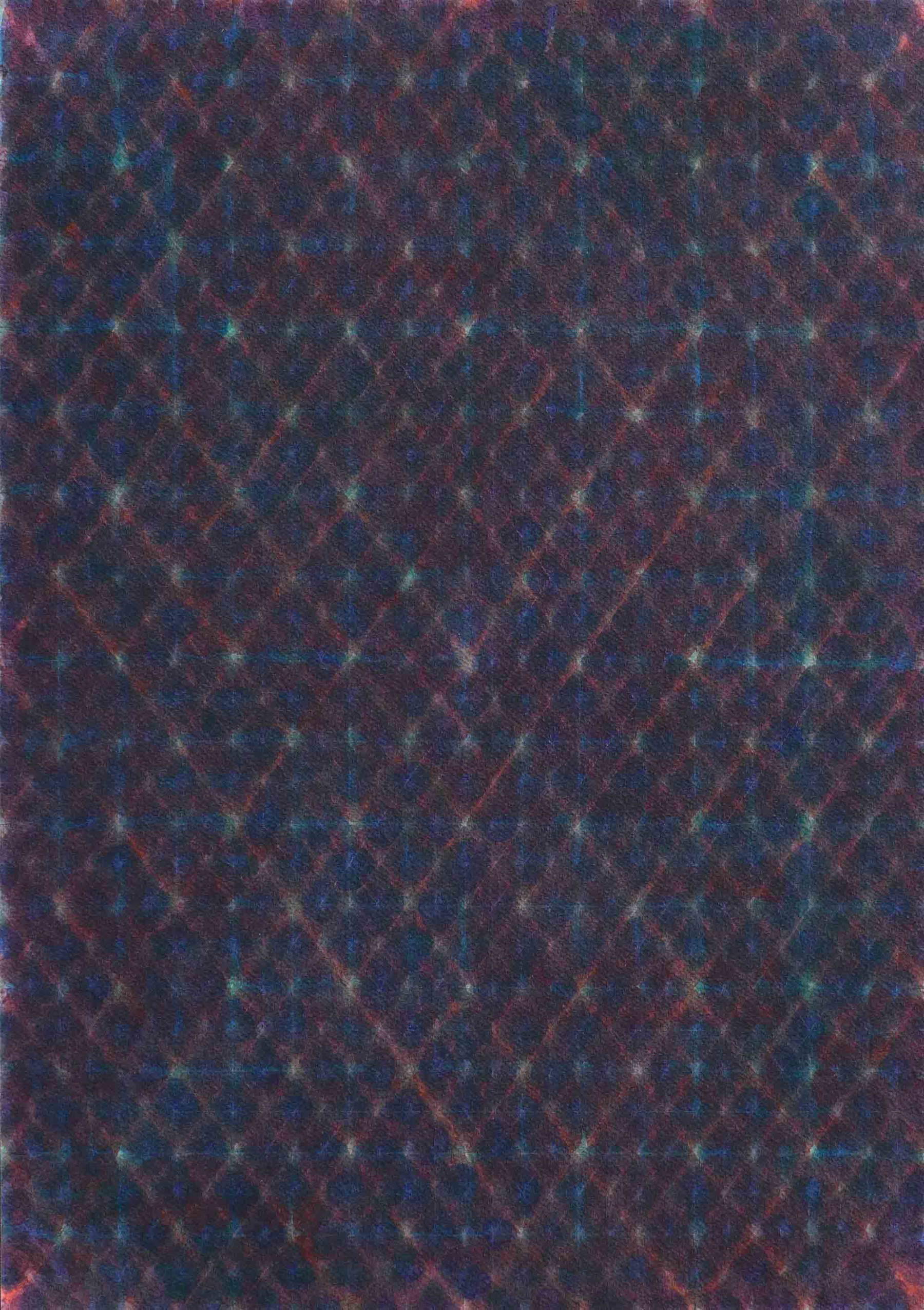

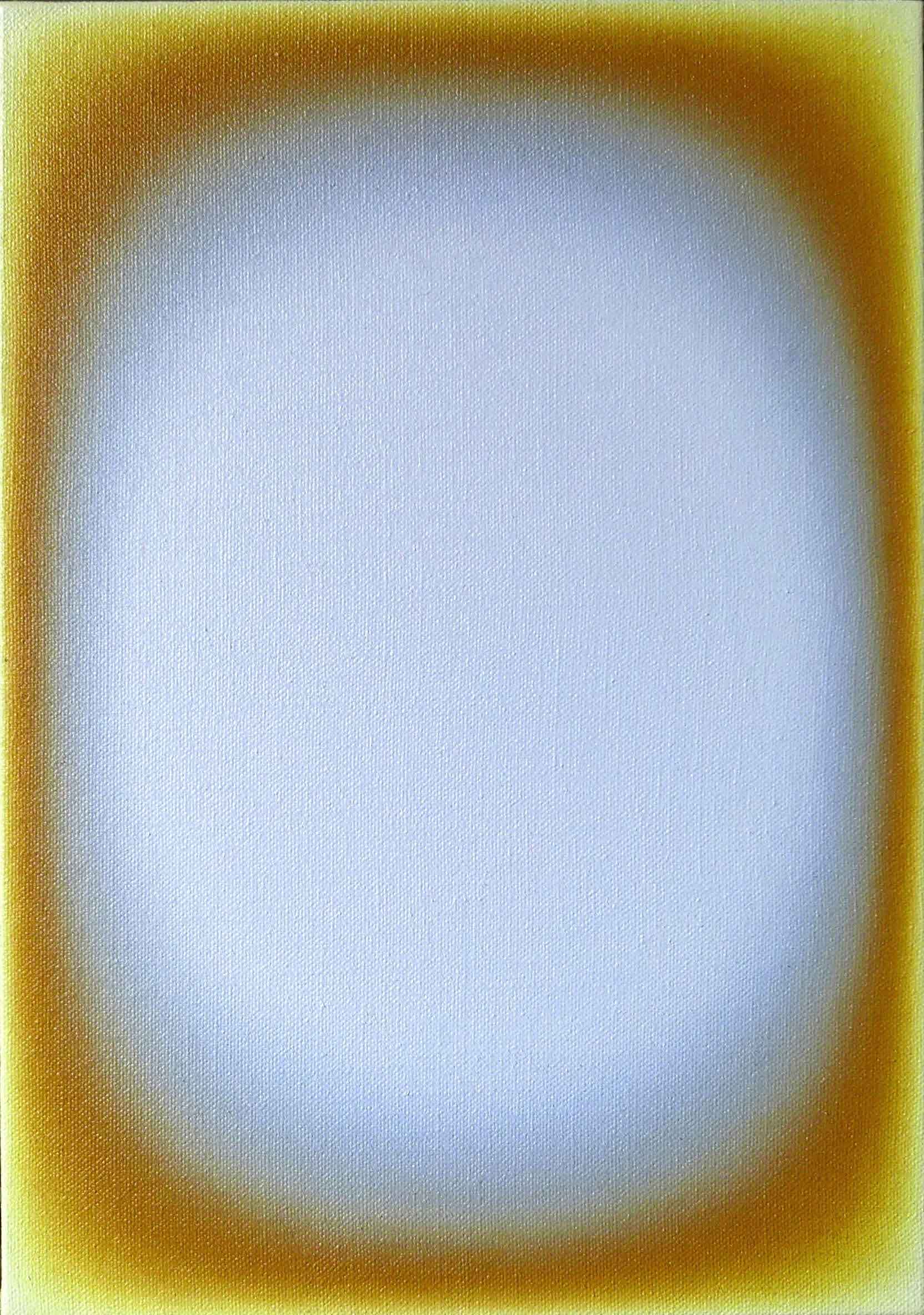

Among the many rebirths you have had in recent years, the latest in chronological order seems to reveal a new dimension, that of expanding color and its intense luminosity. How did you arrive at these works what was the intuition that triggered it?

At one point the artist asks, “and yet there must be a way, a moment of truth without pretense, concessions, fantasies and winks in which to ’be,’ to give everything and nothing outside myself.” This, too, I wonder.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.