"Art is a question that triggers other questions." Conversation with Paolo Cavinato

Paul Cavinato’s (Asola, 1975) research focuses on space and its perception: in his work, the observer becomes an integral part of the work. After graduating in Scenography from the Brera Academy of Fine Arts and taking a film direction course in Milan, starting in 2001 Cavinato has exhibited in several solo shows (Milan, London, Berlin, New York, Santa Fe) and already since 1997 in as many group shows (Paris, Brussels, Istanbul, China and the United States). In 2005 he participated in the Istanbul Biennial and in 2008 he won the 3rd Prize of the Arnaldo Pomodoro Foundation in Milan. He is a laureate of the Royal British Society of Sculptors in London, which dedicated a solo exhibition to him in 2011. In 2014 he was in residence for six months at the Swatch Art Peace Hotel in Shanghai, and in 2017 a major solo exhibition was dedicated to him in the rooms of the Museum of Palazzo Ducale in Mantua. Until Sept. 29, Cavinato is on view at mudaC in Carrara with Direzioni, a solo show in which the artist presents a number of works including Solaris#5 produced specifically for the Apuan museum: the exhibition provided the cue for a conversation in which the artist talks about himself.

GL. Paolo, let’s start from the beginning. For many artists as early as childhood we see the first manifestations of what we might call a propensity toward a certain kind of language, was that the case for you as well?

PC. Yes, it was like that for me too, as a completely natural and spontaneous gesture, but when you are a child you mix creativity, play, fun, expressiveness, boundless communication, all strongly connected to imagination. Then, for most people it all ends, while for me it was a continuum impossible to contain, so, to this day I still feel the compelling need to see and see again, to imagine and realize outside myself, a vision, as a living creature. I remember the drawings and stories written, begun and never ending. And I remember formulating a very clear and very definite thought at one point, and that was the awareness of my being and my wanting to be an artist.

What was your first artistic love?

My first artistic love, if you mean as a stimulus, in creating, was probably my father, who used to paint on Sunday mornings. It should be noted that even at that time my father was doing something else, he worked and still works in mechanical construction. I was a child and watched him paint landscapes and still lifes in oils. I remember the oil, the canvases, the easel filled with crusts of color, the smell and the material. He was painting dechirican, between Carrà and Sironi, metaphysical paintings, while I stood to the side watching and imitating, and my grandfather sat in an armchair smoking a pipe. I should also add that at that time, although ours was a small provincial town in the Mantuan countryside, it already had an art museum, with its own collection, where exhibitions were held and cultural meetings were organized. In short, I was already starting out in a respectable cultural context.

What studies have you done?

I have a diploma in Master of Art and an artistic maturity with a focus on architecture and interior design, obtained at the Art Institute of Mantua (with a strong inclination toward Bauhaus). I then took a course in Scenography at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts and a course in experimental cinema at the School of Cinema in Milan. My training, however, was in and out of the school environment and completely transversal since out of my curiosity from a young age I attended the studios of my professors who were partly artists and practiced the different disciplines of the visual arts. Later on I became interested in cinema and then in the medium of video as an alternative expressive language and in photography by following a workshop led by Guido Guidi, which was really fundamental, to be added to all the work experiences in the field of theatrical scenography, frequentations with directors and artists and the world of art galleries. A totally experimental and schizophrenic period.

Did you make any important encounters during your studies?

The teenage years were quite difficult, of true formation and de-formation, of disappointment and strong discouragement, at times definitely distressing, in which I could not make sense of my restlessness. Certainly important were the encounters with some professors, some of them even disastrous, very bad, very hard. I don’t know why during adolescence you feel so exaggeratedly everything is more amplified, at least for me it was and maybe thinking about it I think it formed an emotional and sensitive substrate. Fortunately, there were the workshops where the plastics of sculpture were worked on, so metals, wood, clay, etc., and the life drawing, geometric, and design courses, which I loved strongly. While on the one hand I was learning a harmonic view of the world, order, the study of classical canons, proportions, Pythagoras, the golden section, the pursuit of beauty, etc., on the other hand, representation was completely turned upside down and chaos, entropy, randomness, disorder were taken into account instead. I was attracted to the various possible looks at reality. Carlo De Simone, my teacher at Brera, left me free in my entirely personal interpretation of theatrical scenography. With him I understood with awareness how theater actually is the place of encounter and exchange between various disciplines and expressive languages. So then was the long and beautiful friendship, with his wife Laura Mancini (the color workshops!), which conveyed to me the importance of perceiving and feeling space, of the possibilities inherent in the human being.

At the Academy you took the Scenography course, why?

It makes me laugh because I actually wanted to enroll in painting! So a choice not chosen, let’s say, a bit imposed, conditioned. I didn’t know and knew absolutely nothing about what set design was. Partly I had been advised by some high school teachers and partly it was a compromise with respect to my parents who did not see this choice of studies of mine very well. Of course if I had done painting or something else today my research would most likely be different. On the positive side, set design made me better understand space and its characteristics, of three-dimensionality, light, movement, sound, with the whole implication of the human figure within it. On the negative side, I can say that I came to the art world, understood as the contemporary art system and art galleries, a little late, but with a rather important wealth of experience.

After you finished your studies did you work in the theatrical field?

Already during the Academy I was collaborating with small Milanese companies in the creation of objects or props, but fundamental was the meeting with the set designer Ezio Frigerio, during a seminar/workshop organized by the Piccolo Teatro in Milan, where I was literally picked up and invited to work as an assistant in his Parisian studio. So for quite a while, on Rue Des Archives, I was drawing and modeling sketches for important opera sets, or designing houses or private residences. A really intense experience living and working in close contact with a great master, an impressive personality! I also do not forget the fact that that Parisian studio then became in the evenings a meeting and debate place for important intellectuals who were friends of Frigerio. At the same time, I was signing some set designs, and collaborating with directors such as Federico Tiezzi and Michael Znaniecki.

Did these experiences prove important for your work as an artist?

In conceiving a new vision of space, my personal research had never stopped. My exhibitions with some of my early installations continued in a relentless search for my own sign, my own identity. But in spite of all these important acquaintances and collaborations, I felt somewhat alienated from the world of theater, and I was experiencing it as an artist, with a different eye, not fully involved. A strange feeling was maturing in me: the play and theater in general seemed to me to be a fake, make-believe staging, and it was, and it had to be! While my work I perceived it as something tangible, true, real, related to truth. I did not understand or appreciate Italian-style theater, where the word and story is predominant over all other languages. I wanted and sought a space of abstraction and experimentation, where all languages interpenetrated in balance and disequilibrium. So I couldn’t stand spoken, word-only theater; it all seemed very similar and redundant. So when I saw and discovered the projects of Societas Raffaello Sanzio and Romeo Castellucci, I was thunderstruck, shocked. From here came a deep crisis and a fairly sharp caesura, I must say: I was not at all satisfied with my path as a set designer, I did not feel like myself but a mere technician at the mercy of the director. Whereas I had very strong ideas and visions of my own about the stage space. So I left the world of theater, although I had done important projects, I felt it was not the right direction.

Your first experiments in painting date back to when?

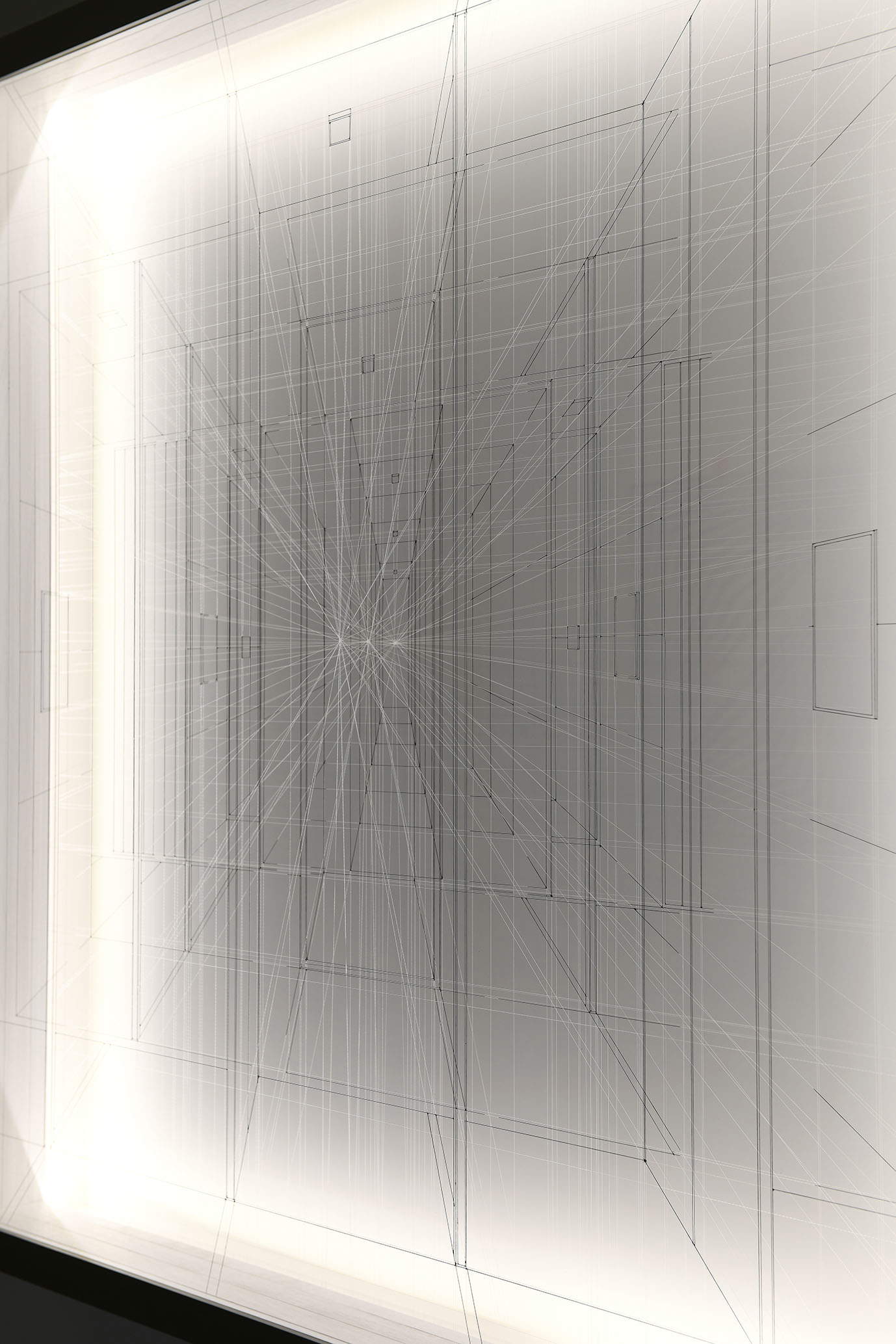

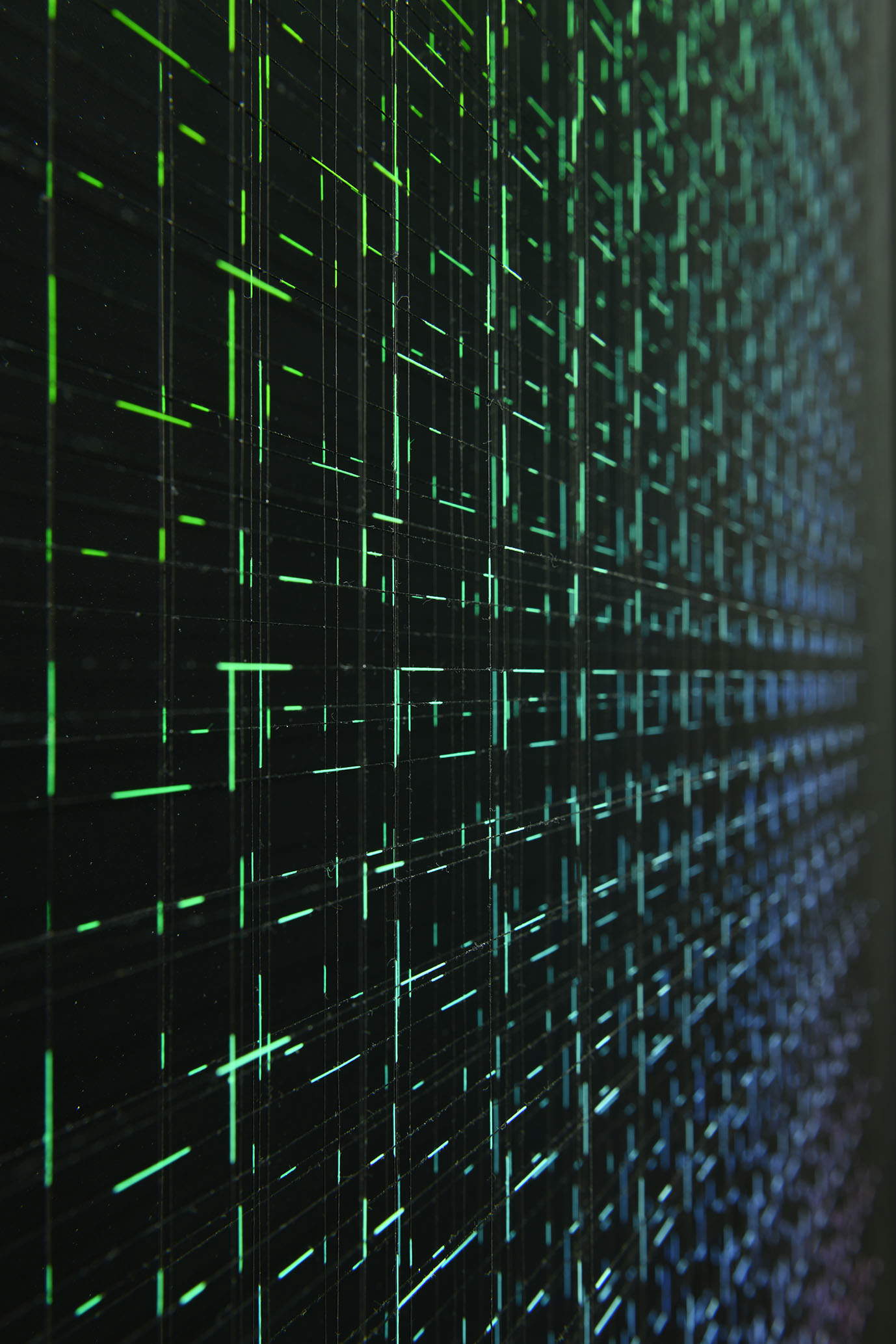

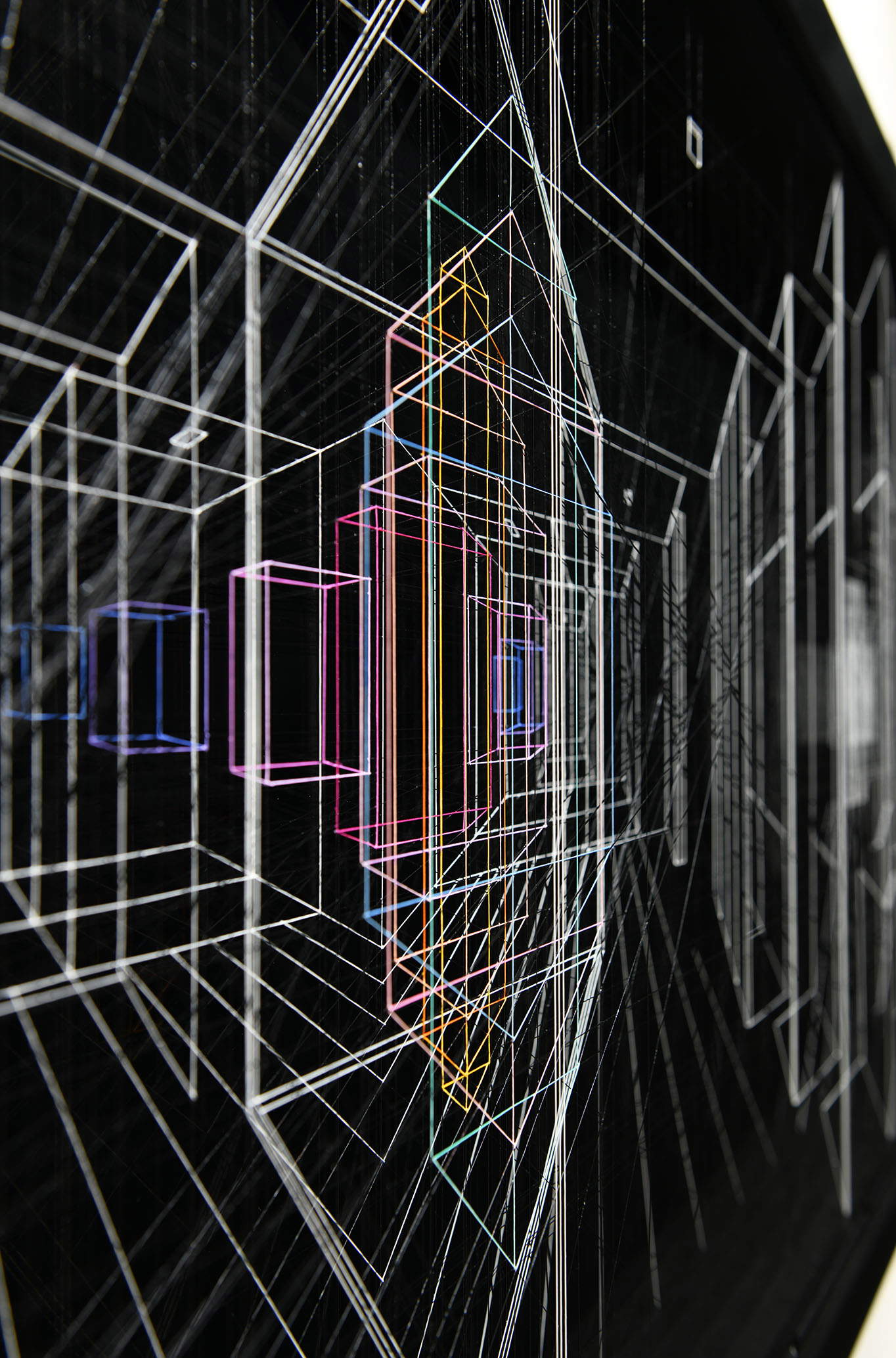

From a young age, but still today, I reflect the meaning of “painting” and the meaning of painting making. Over the years I changed mediums and media, experimenting with light and color up to the latest Iridescences and Textures, true pictorial experiences made of fine particles of light and color on carbon threads. An important period in which I seriously reflected on the meaning of making painting, coming to investigate the physical space outside the painting was undoubtedly between the mid-1990s and 2008, the year of transition and consolidation of installations and anamorphic rooms, from CamerAptica, Soglia, Annunciation and Reflections

What kind of work were you doing?

The pictorial surface was like a screen-mirror and alchemical mirror, black and then white, on which I let organic, natural materials (earths, powders, leaves, woods, minerals, etc.) settle, which then in gestural succession, became “spatial.” After abandoning all illustrative and representational traces, first surrealist, then symbolist and more expressionist, I investigated the surface of the painting as a spatial concept, a threshold, a living cutout of experience.

From these two-dimensional experiences, how does your path to space and the third dimension evolve?

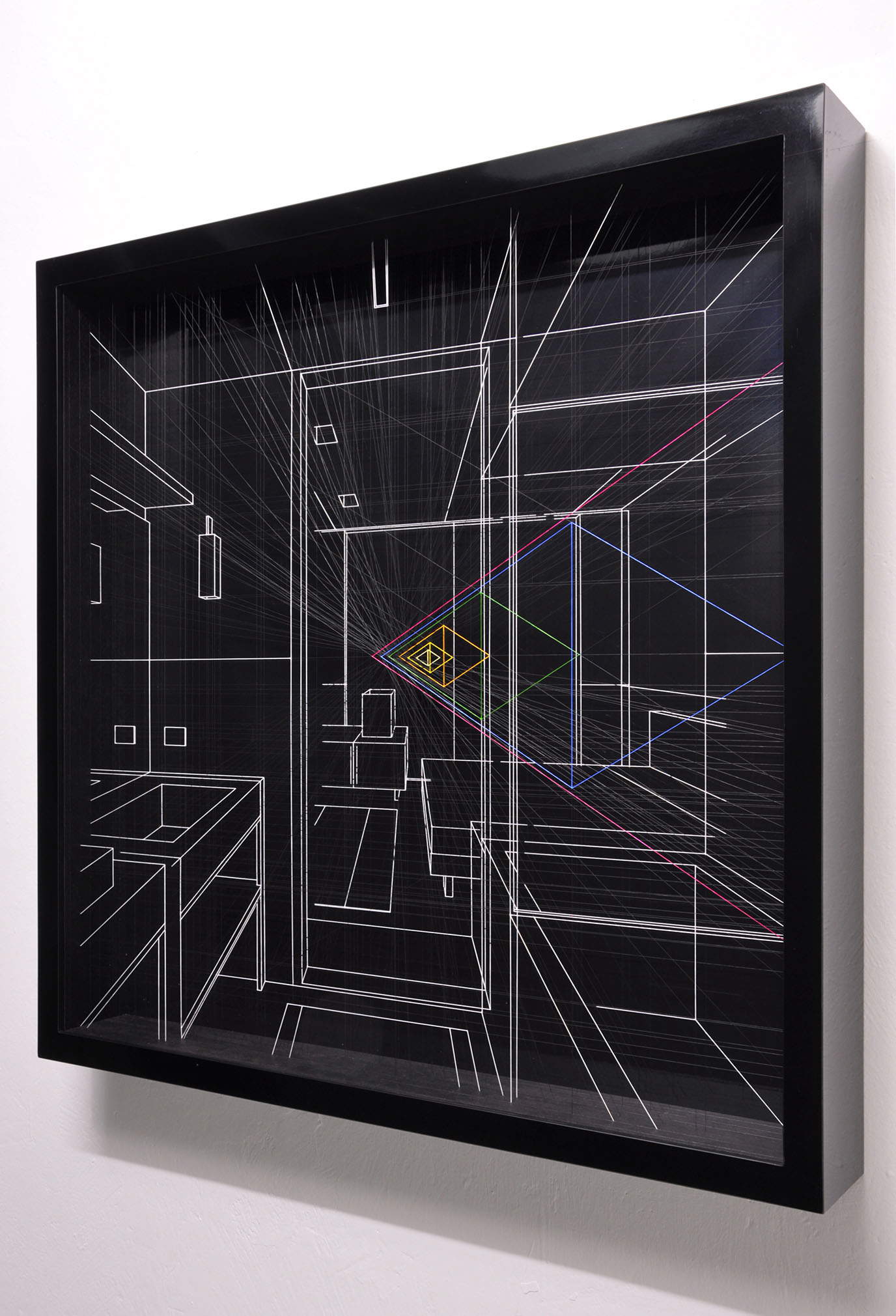

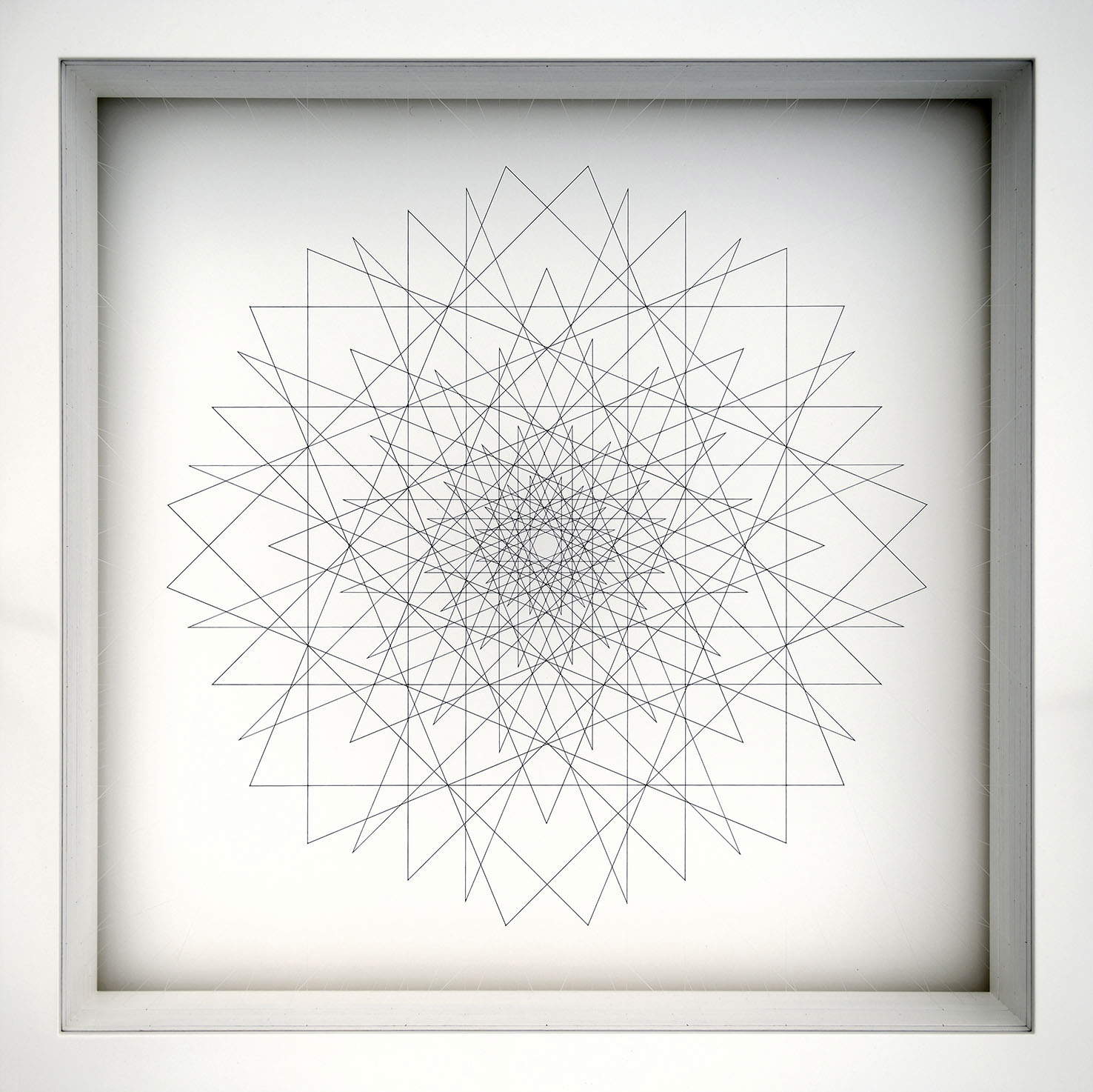

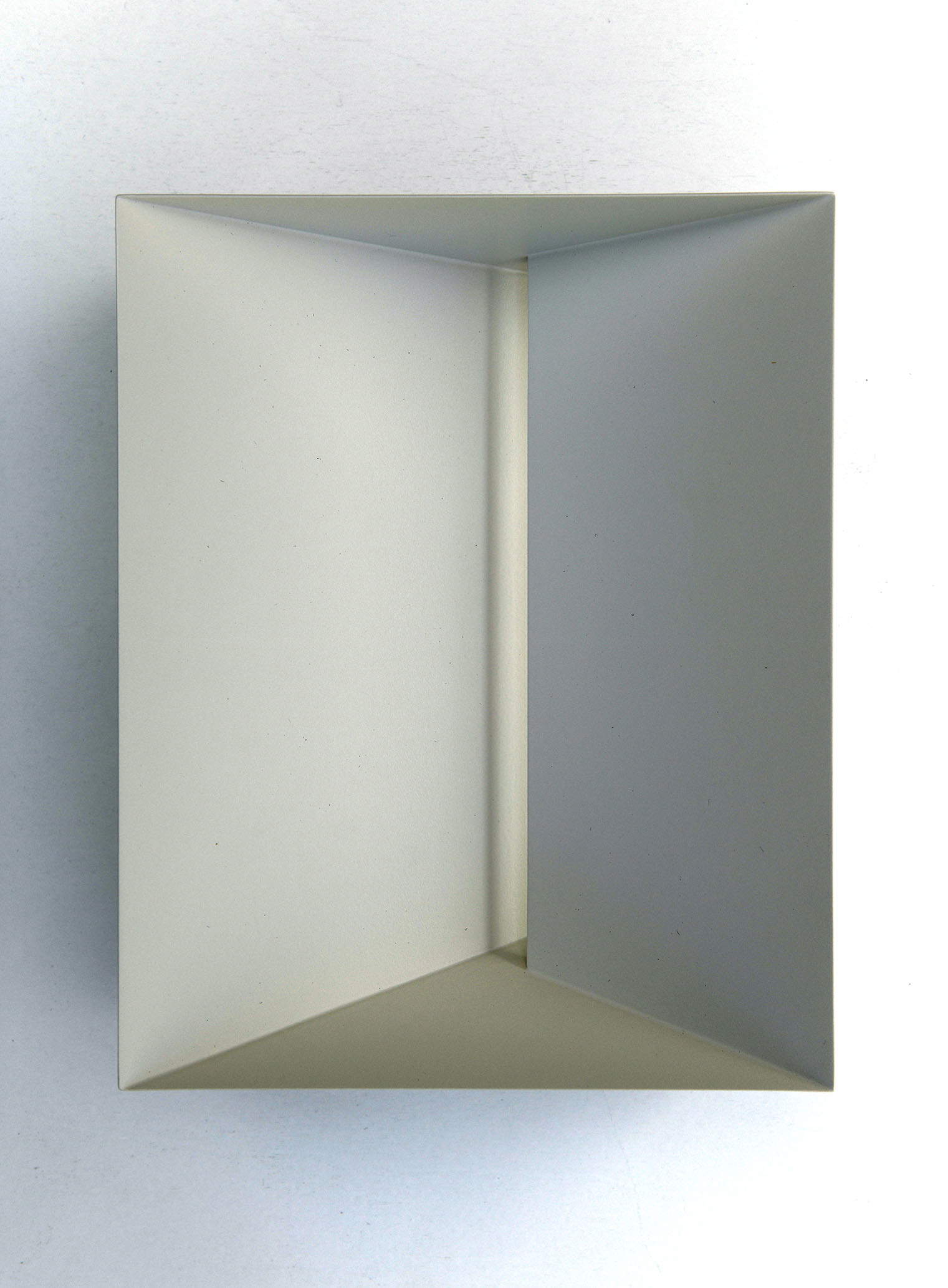

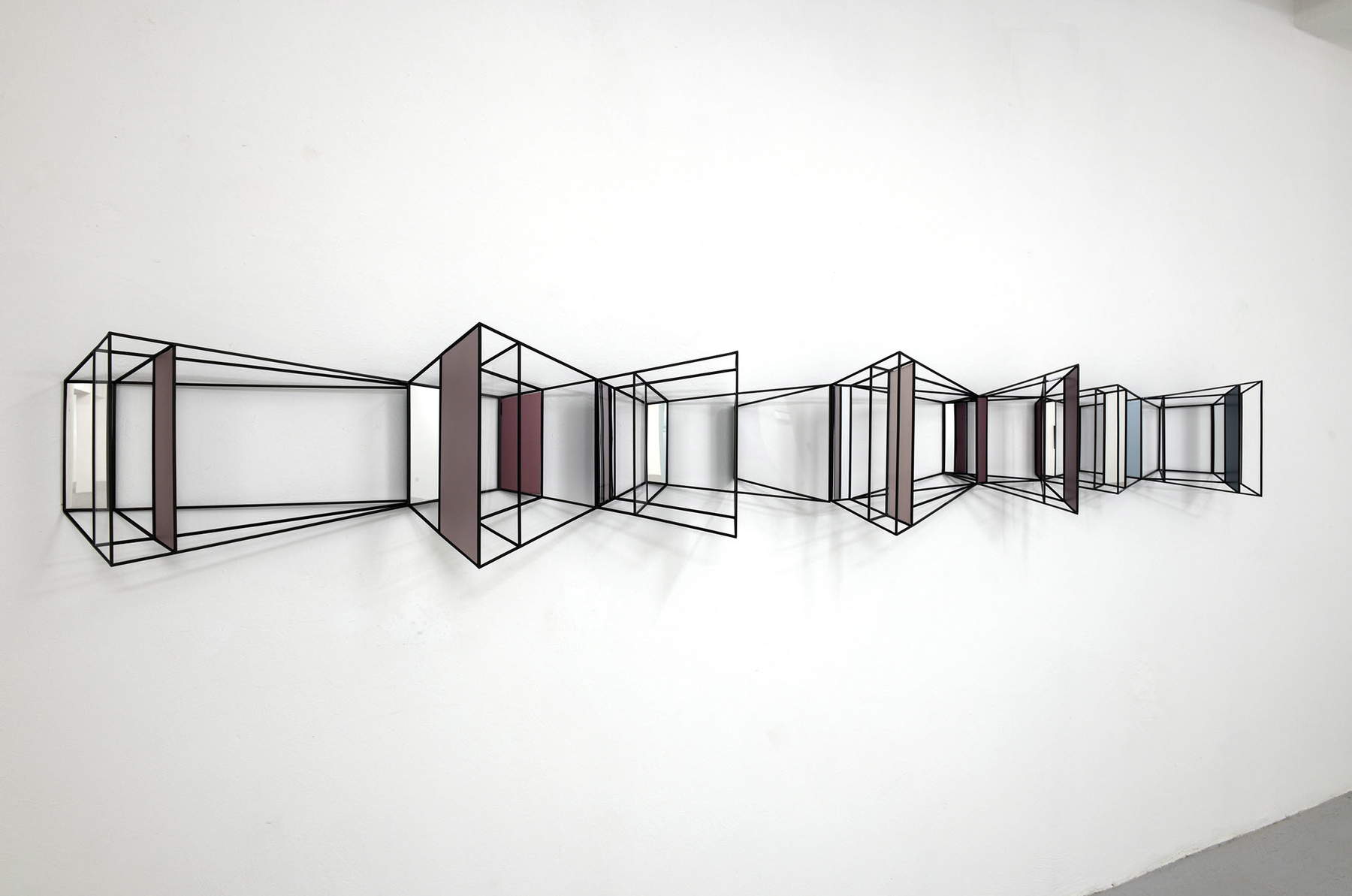

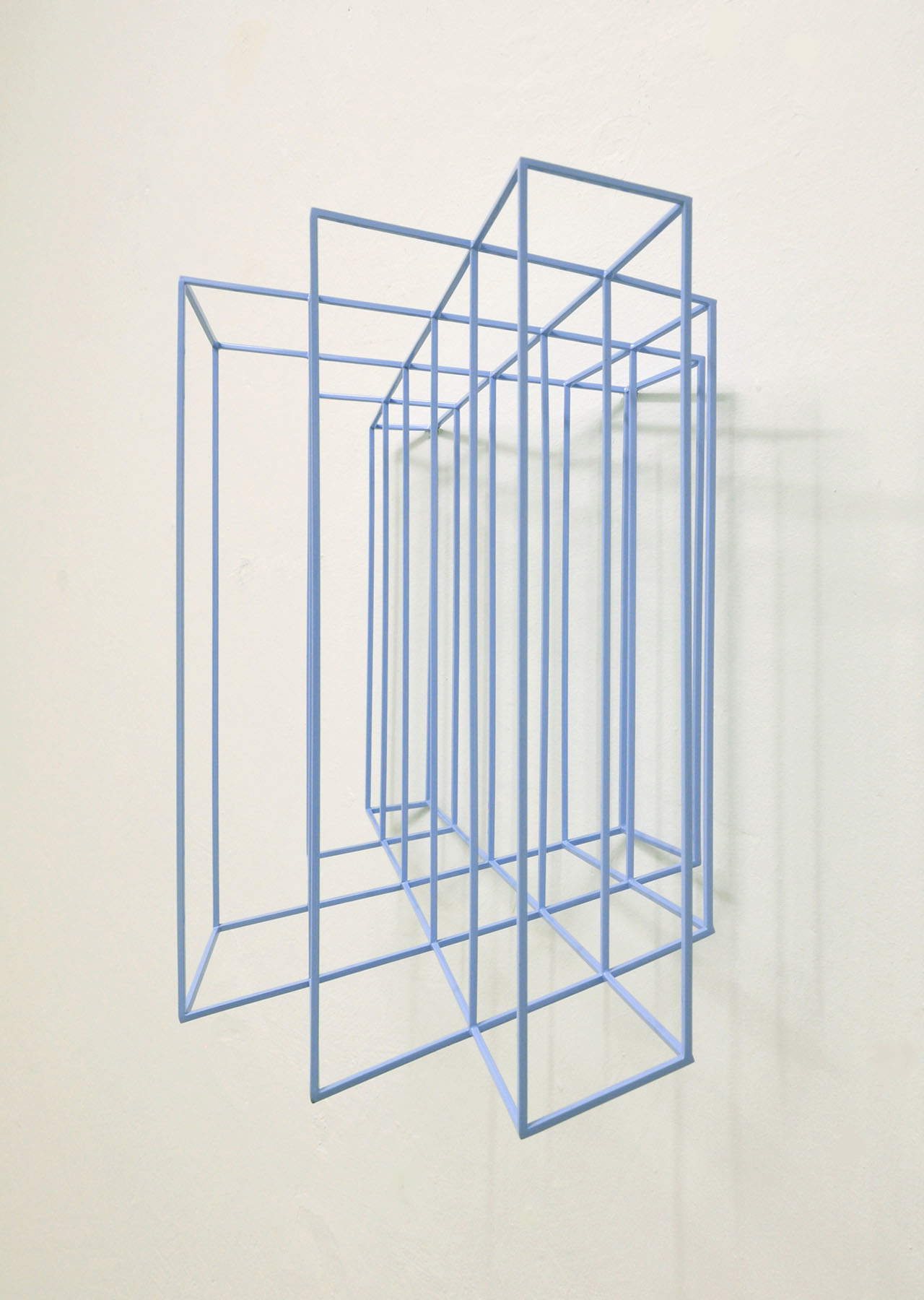

In my teenage years I represented interiors, rooms as boxes, or vice versa, where a special interest in three-dimensionality, theatricality, staging, storytelling, interiority, and so on, was already evident. Then later, precisely between 2007 and 2008, working on surfaces as an alchemical mirror, entropic space, chaos, I started to include elements of perspective, starting from the horizon, and reconstructing space according to mathematical orders. So between chaos and order. The pictorial surfaces, of canvases and wood panels, soaked in hard materials like walls, became the impetus for projecting elements, of objects enclosing a life, sometimes of dripping water, then also inserting the idea of rhythm and time, of expanding elements, and following the evolution, I moved on to the real installations and the whole discourse related to looking and gazing. More recently, I have returned to the discourse of the “picture,” taking up the ancient scientific, Renaissance, Brunelleschian perspective machine, making an important reflection on our cultural sense of looking: the gaze fixes on some defined and organized points and then branches out and pushes out following directions on the field of space. All space arises from a point, from how we look at it. Today, beyond surfaces, the gaze has gone into the matter of particles and their relations in empty space. I do not forget the experiences in Turkey and China and learning a different conception of reading space.

What prompted you to devote yourself to sculpture and installation?

The history of art and its evolution. I found the concept of mimesis, as an idea of an illustrative painting or sculpture, exhausted and no longer relevant. I was interested in an art supporting more existential and contingent, real reflections. As I explained I investigated the pictorial surface as a reflection of space, opening up to the whole, and how certain emotions invade space, like air and light. Let’s not forget all the studies done on avant-garde art and otherwise. How can we stitch up Fontana’s cut? So it couldn’t be any other way, given my path, even though even today I can’t consider myself a sculptor, not having a purely technical sculptural training, I go outside the term, I feel like a visual researcher, of space. But sometimes I really feel the very terms of painting and sculpture, as means and categories of expression, are exhausted. What is painting and what is sculpture today? Perhaps in these terms I feel more related to drawing, but my making includes a conceptual discourse about looking, about looking, about observing.

In your work what importance do time and space have?

The Sun, with its movement determines the concepts of space and time, they are our dimensions of daily living, but they are only two of the many dimensions at play. We live our reality without realizing the multiple structures behind it, and perhaps fortunately! We are made of particles and relationships, and traversed by waves of energy (now as I think and write here I myself am being traversed by other dimensions), and we are mostly made of emptiness. We know almost nothing, and that terrifies and fascinates me at the same time. So my very recent Codes, they are seen as mysterious and incomprehensible alphabets, or they reveal themselves in precise forms in space from predetermined points. But time and space are not rigid, they expand or shrink, they move and change. All our history (as well as the history of art) follows dynamism, just as human evolution follows a direction, a looking ahead. When I think of my video experiments, which were already true pictorial paintings in motion, composed as if they were music, today in installations including Breaths and Lost, light cuts appear and disappear like echoes in empty space. In Beyond the human figure, indeed, the self, the us, our being gives way to a straight path, suddenly expanding like a gap in front of or inside us.

When you make an exhibition are you interested in the idea of staging the work?

Staging follows an idea of storytelling, as there is a hierarchy and therefore a politics in establishing positions. I like to design the staging following a path idea. It is important to make the objects, the works, and at the same time to think of them already placed in a space or in relation to each other. Probably, one thing that has stayed with me about theater is the aspect of waiting and happening, of operating so that a kind of catharsis is achieved. Theater is a ritual that has a collective sacredness, as a kind of event, a collective experience or epiphany, but sometimes solitary, intimate.

What kind of relationship do you seek with the spaces you exhibit in?

I love to challenge myself every time by making a new experience. I want to know what the spaces are made of, what light is shining through them, what materials they are composed of, their proportions, shapes, heights, dimensions, whether there are historical traces or not, all of which consolidates a kind of aura of the place. Try to capture it and then incorporate some existing or purpose-built elements. Thinking about how the user will be able to move around inside. It all comes within the framework of design, calculation, measurement, and construction. As I move forward, the layout becomes more and more important, and it is not just a matter of making objects but how to place them in relation to each other and the space.

Are you interested in the idea of artwork as an immersive experience?

It is a term that is very much in fashion today, I don’t know if we are experiencing some kind of great misunderstanding between art and creativity (as an entertainment event), or that this is the current direction of art? We are increasingly involved in immersive, effects-based, sensory, perceptually engaging installations that don’t ask for anything. Are museums or cities being turned into amusement parks? I wonder more and more, however, what is art and entertainment. I am not much attracted to these kinds of experiences; I am interested in the potential inherent and held in the work of art, capable of revealing itself to the public even in the intimate as a manifestation of the human condition. Years ago, the haptic space, present in Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis and further explored later by Gilles Deleuze, had suggested to me these possibilities, of seeing with hearing or with smell, that is, of a heightened view of the other senses. I was interested in synaesthetic discourse applied to space. Today I am more and more interested in the “minimum,” in absence, in the idea of margin, of limit, I prefer humility to bombastic effects.

Sometimes your installations are accompanied by work on the musical dimension: how did this experience come about and what developments has it had over time?

People mistakenly think of it as a kind of musical accompaniment, whereas it is a true fusion, a weaving of the material of the work and not a soundtrack applied on top and at a later time... This dimension also comes from my video experience (1995-2006), where I was interested in the construction of images often starting from tangible reality, and then transforming it to real pictorial paintings in motion, and then during the editing of editing, as if they were musical compositions. With our friend, composer Stefano Trevisi, we began the collaboration in 2006, starting from visual and sound fragments (produced by real musical instruments) that were recomposed according to established points in space. The first installations made together were conceived precisely as experiments between different sensations and media. So the visual, the plastic materiala, and the sound as dynamic componete, then, the lights and electrical control units and timers to create real kinetic machines. So of visual and sound space in motion. The experiences were successive and diverse. From a creative dialogue where music and sculpture interpenetrated, in some cases I would be inspired by certain sounds of his or vice versa I would ask Stephen to make certain sounds on sculptural elements. For example, in Lost, conceived and realized in Shanghai (during a six-month residency of mine at the Swatch Art Peace Hotel), he was waiting for a musical part of it, so I asked him to elaborate some Chinese gongs to be inserted and dialogue with the light part of the work.

In your opinion, does a work of art exist even in the absence of a user?

A good question. Unlike an event of objective character or an autonomous organism, art cannot exist if it is not experienced by anyone. Being a set of rules, as a system of meaning, it exists at the moment we perceive it and make sense of it. May it therefore be a reflection of man? Art is a question that triggers other questions. We search for the invisible, which reveals itself only at the moment we receive it. Art is a fact, but it is a system to which we alone give meaning. But the objects are there, and perhaps they already exist (in the imagination?), and perhaps it is a matter of bringing them out of oblivion? But if they emerge does that mean that they exist and are only hidden?

What kind of relationship do you seek with the audience that comes in contact with your work?

I want to focus on the work and its manifestation, taking care of its setting, and once it is finished, I stand aside to observe, to observe the work from the audience’s side and to observe the audience observing the work.

Most of your works represent spaces that could not exist without humans. His presence is often suggested, evoked. Do you ever get the urge to represent figures within your works?

In my work the viewer becomes an integral part of it. It is me looking, me understood as a person, me standing here, now, choosing and becoming aware of my current state. In some works such as Phantasma and Reflections, the viewer himself vanishes, and becomes a ghost. Just as in Threshold and Beyond, he sees his own image vanishing within the deep corridor. In Protection, he becomes pure calculation and inner, infinite projection. In all the works made as drawings with painted threads, it is we who look. Years ago I inserted the figure, dismembered into fragments, between surrealism and cubism. Then in silhouette form, shadow, until it vanished altogether. Shadow, light and emptiness. Today the figure is the viewer who observes, and the empty space becomes a mirror in the form of a “thinking room” almost. Reflect and measure oneself. It is necessary to create emptiness, the vibration of emptiness, its presence must remain sensitive.

In the more recent works there is a pattern of marks that reminds one of some of the experiences of optical art, are you interested in this art form?

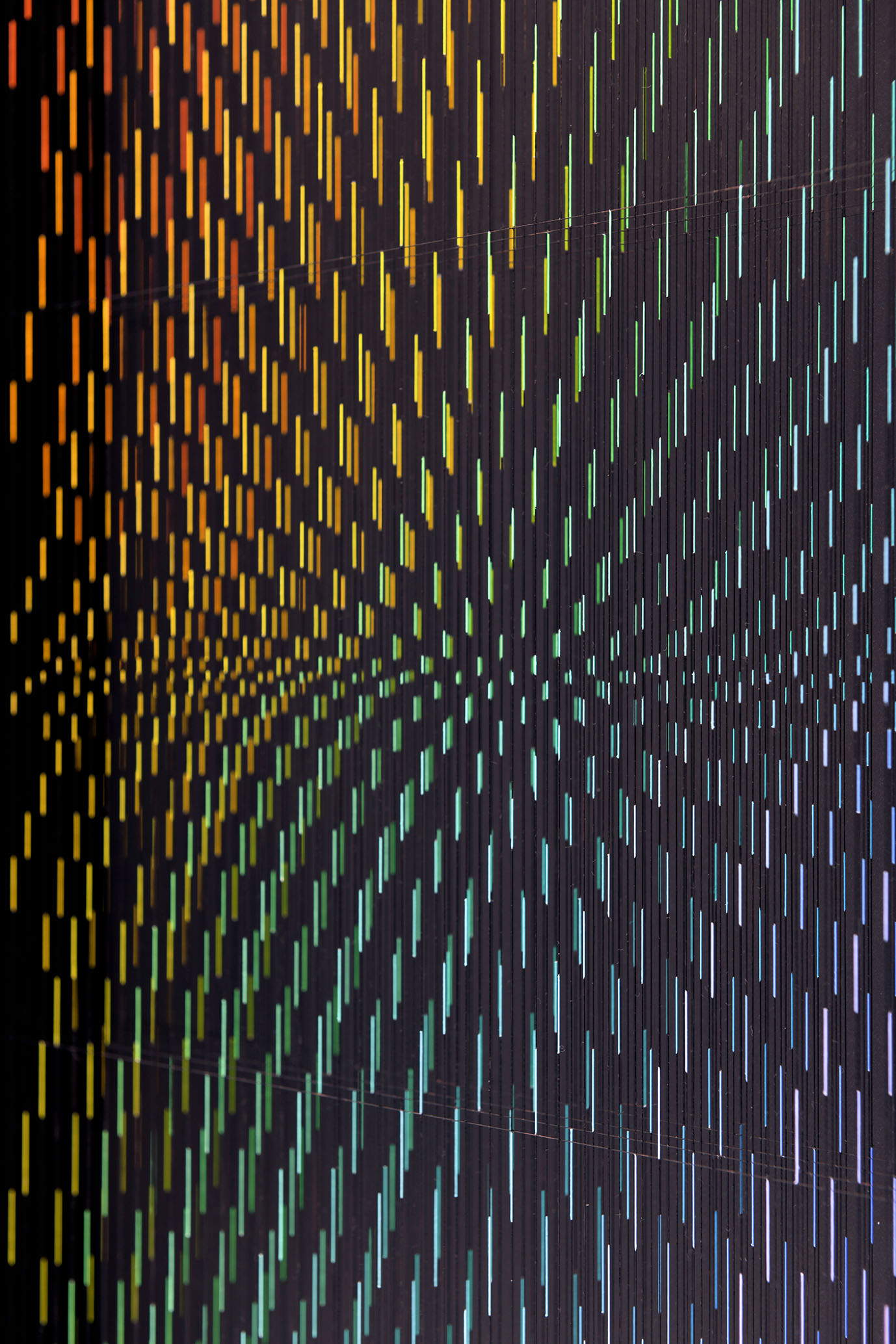

I am not very fond of it, I must say, although the public often misunderstands this path of research of mine. I am more interested in Gestalt principles. Over the years I have become interested in the representation of the image, in space, in how it is represented and therefore how it is perceived, in painting, in the surface of the field. There is an underlying question about what is representation and the realization that after all, we are also children of the twentieth century and all its research addressed. As for Waves, my gaze goes beyond perspective and representation. Countless particles of light, between solids and voids, of different lengths and hues, form an alternating series of gravitational waves and like oscillations of energy, propagate through space forming an iridescent pictorial surface, almost as if it were a living body in motion and transformation. I am thinking of recent scientific research in quantum physics, but I am also thinking of the important and revolutionary studies on color and especially on “Spherical Color” by the German painter and scholar Philipp Otto Runge.

Are you interested in a sacred dimension of art?

“The divine light is penetrating the universe according to what is worthy”: Dante Alighieri, Paradiso. The sacred has accompanied man in all his historical eras founding cultures and thoughts. It has followed the need to seek the mystery, to ponder the question. So too, my upbringing, strongly Catholic from childhood, has certainly conditioned my thinking and acting. I have sometimes wondered how I would have been, and how I still would be, if I had been born in an atheistic culture, devoid of spiritual thought, what implications it would have had in my life and in my inner search. Having had a God of reference sensitized me in asking myself a constant question, as a presence in life and things, an attraction to a mystery. Today I live a continuous reflection or meditation, a kind of spiritual exercise, of breathing, which is linked to a totalizing feeling, to a total dedication to my art. Some research has pushed me toward an indefinite “place” that we can call “elsewhere.” One step further and further, moving away from matter to embrace an “other,” luminous dimension.

Drawing seems to me to play a central role in what you do not only from a design point of view, can you tell something about that?

Drawing has accompanied me since my childhood. Over the years it has thinned out to the point of almost completely erasing itself and today although it is there, it appears and disappears at times, it is invisible, although it can be seen, and it sustains an ephemeral, light image, supported in the void. The design then is the foundation for regulating proportions, measurements of space, linked to something mental and immaterial. My gaze is measurement and calculation, as if every time, even simply observing reality, I am looking for a proportion and a relationship between things. I don’t think it’s an obsession, I do it instinctively and naturally. So the drawing that has been the main engine of my whole path, today to a large extent remains hidden, invisible almost. What the audience observes in my work is like an indication, a traced and colored part of a whole that remains underneath, invisible, supporting the work.

Some artists stand to the side of what they are doing (e.g., Giulio Paolini), others look at it from above, some like certain performers are themselves the center of it. Where do you place yourself in relation to your work?

I wonder where they, the works, stand in relation to us, because as Enzo Cucchi says, “works that work have eyes and legs,” and that is very true. The gazes are multiple. My posing comes directly from the inside since my works are often made at multiple levels, in multiple stages and long in time, over months and even years, in fragments that are then built up by magic only at the end during the installation, but at the end, I myself stand to the side to look at them through the eyes of the audience, to look at them differently.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.