Time is out of joint, the “new installation in the form of an exhibition” at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome, curated by Cristiana Collu, has had the effect of creating two opposing factions: that of critics and that of enthusiasts. We have decided to publish, in the pages of Finestre sull’Arte, two interviews: one with director Cristiana Collu (for whom we have received availability and which we hope to obtain as soon as possible) and one with Claudio Gamba, a scholar of unquestionable authority, who from the earliest days has proved to be one of the most critical voices towards Time is out of joint. Today, therefore, we publish an interview with Claudio Gamba, an art historian who, as we read on his website, “has dealt mainly with Italian sculpture between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries and with the history of twentieth-century art criticism,” but also with issues related to protection by actively collaborating with the Associazione Bianchi Bandinelli, has curated exhibitions, has numerous prestigious publications to his credit and teaches at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera.

|

| A room in the National Gallery’s new installation. From left Contemporary Crucifixion Cycle of Protest No. 4 by Emilio Vedova (1953), Great Red P.N. 18 by Alberto Burri (1964) and the Battle of San Martino by Michele Cammarano (1880-1883). The sculpture is by Leoncillo. Photo by Luca Zuccala |

Dr. Gamba, you are one of the scholars most critical of “Time is out of Joint,” which runs through April 2018. Let’s start right away with a seemingly simple question: what do you think are the most objectionable points of the operation to which the Gallery has been subjected?

I am undoubtedly very critical of the new layout, I consider it on the whole a wrong operation for the type of museum and collections on which it has been intervened, but before clarifying my position further I would like to premise that the severe judgments I intend to make are addressed to Cristiana Collu as a director and not as a scholar and intellectual. In fact in some ways I admire her decisionism, her will to leave her personal mark on our time; behind her seemingly oblique, coy, elusive figure, there is actually a woman with very clear ideas and surprising determination, to the point of not feeling the need to listen to the opinion of the scientific committee of the Gallery she herself directs. When these gifts of hers were used to create a museum in a peripheral area isolated from the great international circuits such as the Man in Nuoro and then to some extent at the Mart in Rovereto, the results were very interesting; but this unscrupulousness came to clash with the assignment she obtained following the ministerial reform of museums, as director of the most important collection of Italian and partly European art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a true place of national identity and then a center of innovation and critical debate after World War II. It is one thing to operate in a new context, in an empty container, to set up a Biennale, to hold exhibitions in the provinces, or to rearrange a museum with a small collection of unequal value; it is another thing to measure oneself against a symbol, a canon of cultural values, with the sedimentation of a century of critical and museological historiography as it is in the case of the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art. The first questionable point, I would say the sin of origin, was the decision to empty out the entire museum, using Bazzani’s building as a container for exhibitions, as if it were the Palazzo delle Esposizioni where the Quadriennale recently opened. In this operation, of an unprecedented curatorial arrogance, they proceeded with the scythe (and in some cases with the hammer), erasing all traces of the previous arrangements (the result of decades of study and research), dismantling the entire historical layout and, above all, sending back to storage a large part of the nineteenth-century collections, which Collu clearly said she did not know about. All other critical remarks descend from here, from failing to understand that she was not appointed director of MAXXI or MACRO: the first thing a museum director must do is to study the history of the institution and the collections, to measure himself with shrewdness and humility to the works, especially if Canova, Hayez, Medardo Rosso, Morandi, Burri are involved, just to say some random names. We would have avoided this maze of meaninglessness that the Gallery has now become.

|

| One of the most talked-about rooms in the National Gallery’s new layout. In the background Spoglia d’oro su spine d’acacia by Giuseppe Perrone (2002) in front of Hercules and Lica by Antonio Canova (1795-1815) and in the foreground 32 mq di mare circa by Pino Pascali (1967). Photo by Luca Zuccala |

“Bazzani’s building as an exhibition container”: this point is the focus of much of the commentary of most critics. Indeed, a large part of those who criticize “Time is out of joint” argue that the logic of the new display resembles the same logic on the basis of which various exhibitions are set up, especially those whose success (especially commercial) is believed to depend on “eye-catching” operations, on the ability of the display to arouse priceless emotions, on the ability to create hype: this, however, often comes at the expense of such exceedingly important aspects of museum (and even exhibition) life as didactics, contextualization, research, and, as you noted, the historical framework and collections themselves. In short, have we now gone down the road of a “corporate” view of the museum? Or can we still invent a new yardstick for measuring the success of an exhibition or display that truly takes into account all aspects of the life of a collection, a museum, an exhibition?

Behind this operation can certainly also be seen a component of the so-called “revenue-raising” of cultural heritage, which is much more interested in the quantity of visitors than in the quality and duration of virtuous effects on the public, effects that in truth in the long run pay off much more in economic terms as well. In this sense, the radical subversion of the Gallery has the clear purpose of gaining maximum media visibility, a form of scrapping that satisfies the climate of anti-system and anti-intellectual polemic in which we are immersed, which identifies all evils with previous management and technical professionalism; many people need only be told that everything has been renewed to make them happy, but we have a duty to distinguish the new that innovates from the new that confuses. I do not believe, however, that we can reduce everything to the need to quickly manifest the political effects of “renewal” related to the new director appointments desired by the minister. Other directors have made choices in a direction opposite to that desired by Cristiana Collu, who has, moreover, justified her choices with disruptive statements that cannot simply be ignored. The basic idea is that a museum is not a textbook, that art history should be studied at school or university not in the exhibition halls, which would instead be places to experience emotions, to come into contact with beauty. Moreover, the main event that accompanies the new exhibition is connected to these themes, namely the Beauty contest directed by the Spanish artist Paco Cao (who had already collaborated with Collu at the Mart), with whom I have long polemicized; it is a beauty contest that will award prizes for the most beautiful portraits, male and female, chosen from 70 works in the museum, voted on without considering the style of the artists or even the character portrayed, as the rules proclaim, with the idea, in short, that the museum should chase the tastes of certain television audiences. The museum as a kind of location where one can take selfies to share on social networks, where one can take a tour without feeling embarrassed about the things one does not know, leaving fulfilled and satisfied without an iota of cultural growth: if this was what was sought then surely the new layout has achieved its purpose. To substantiate her thesis the director used the argument that there is a healthy anarchy, a pleasing disorder, reflecting our time in which we are bombarded with images and information without linear order and logic. Time would then be hopelessly unstructured, works of art would exist only in our perception crushed on a perennial present, the museum should therefore reject chronological order, hierarchies of meanings and values, in order to produce emotions and short circuits, as is obsessively repeated today. In reality if we then go to visit the new Gnam the juxtapositions often turn out to be trivial and inconsistent, some times the works are associated for a theme, others for a color or a graphic element, in the rest of the cases the reason for the association remains, at least for me, impenetrable. Not to mention that there are enormous problems of fruition, that the most intuitive museographic logics are not respected, such as the projection of videos next to the paintings, with the result that for the paintings the light is insufficient and for the videos it is excessive; the drawings that cannot bear all that light for months, the neoclassical sculptures on the floor against which one easily risks clumping, the absence of benches to sit on and any educational support that explains the theme of the rooms. But even passing over all this, I disagree in its central assumption with the claim that the museum has nothing to do with art history, with schooling, with education, with the possibility of understanding and confronting the history of the past in terms of awareness. History and geography, like art history and literature, can be taught poorly as sterile notionism but can also, at all ages, be part of an experience of deep and lasting personal growth that makes better citizens, collaborative participants in the whole of society. Reducing everything to emotions, which are important vehicles of initial stimuli but not the goal of knowledge, produces visitors who do not grow, who “consume” the museum, without feeling the need to return except for a new event or a radical refitting, incidentally already planned in a year and a half. In short, a colossal spinning mechanism. All this starts from the misconception, denounced by at least a century of aesthetic and critical debate, that works of figurative art are immediately comprehensible at a glance, whereas one needs to know the grammar and syntax of the visual, then technical, historical, iconographic skills are needed, and for all the avant-gardes theoretical references to proclamations and manifestos are needed. So-called works of art are then not just expressions of beauty: if I examine the verist portraits of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie, the Risorgimento battle scenes, the fascist propaganda paintings, the kinetic-visual researches of the 1970s, the concept of beauty is not only not enough but misleading. All these problems have simply been dissolved in the aproblematic and confusing postmodern scenario assembled in the new Gallery. I stress, however, that mine is not a reactionary position that reacts stymiedly to Collu’s futuristic innovations; her theses are actually at least thirty years old, but while in the 1980s they might have had a beneficial effect in contesting the great ideologies, the Cold War, and dogmatic philosophical thoughts, today they appear to be mere mirroring of our liquid and precarious society, without the capacity to analyze and criticize it. Instead, for several years there has been a discussion about how to get out of postmodernism and posthistory. Here I would like to focus on this approach, which is definitely more innovative than the supposed deconstructive anarchy proclaimed by the director.

|

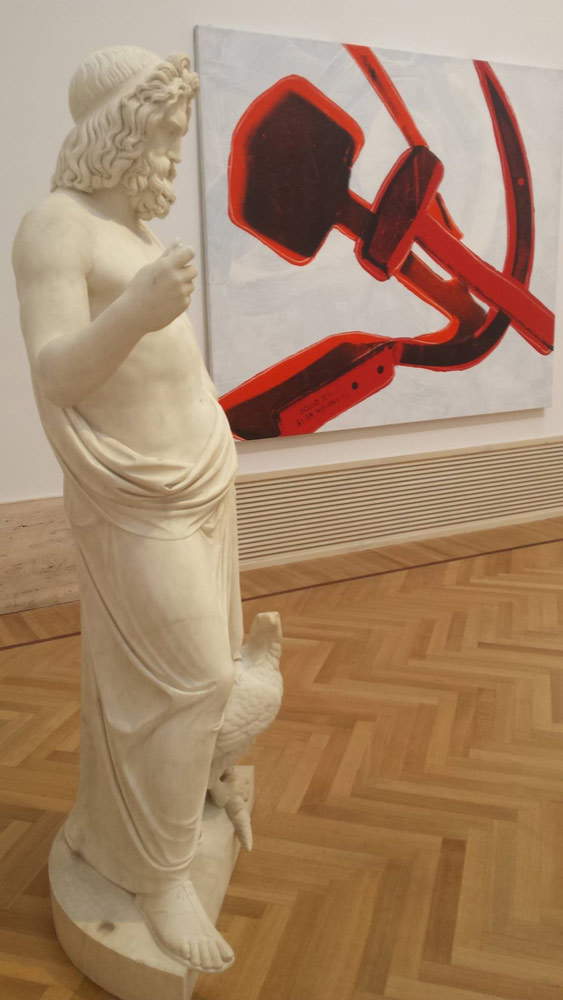

| On the wall Andy Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle (1977). In the foreground is Pietro Galli’s Jupiter (1838). Photo by Luca Zuccala |

Cristiana Collu, after all, has never made a secret of the fact that for her a museum is not an art history textbook and that the museum is not and should not be only a place of education and instruction but also a place of socialization. Are these two visions so antithetical, irreconcilable? It is true that the concept of the work of art as a mere instrument of emotion is outdated, and museography can safely disregard approaches based on pure emotions. However, it must be said that such approaches still find wide acceptance not only among the public but also, and the National Gallery case I think proves it, among the curators themselves: what is the best solution? Do we have to resign ourselves to a (falsely) aestheticizing art history, do we have to sacrifice certain aspects in the name of knowledge, or still can there be a compromise that can avoid making the mechanism run amok?

Personally, I see no contradiction between a place of education and a place of socialization. Isn’t school a place of learning and at the same time the place where each of us has had some of the most important experiences in dealing with others? And not so much with the friends we choose but with the people who happen to be around us: this undoubtedly makes school a fundamental experiment in sociality in which knowledge is shared. For me, the museum has to go in this direction. Then, as I have said, there are good teachers and bad teachers, but in its essential cognitive and pedagogical intent, the school is undoubtedly one of the components of the museum’s identity and has been since the very origins of the first public museums, which had as their purpose the education of good taste for visitors and the training of artists through works deemed exemplary. The museum then became many different things; science museums, natural history museums, anthropological museums, museums that tell the story of labor history were born. All these museums cannot be enjoyed using beauty as a category of approach. When faced with a room with the evolution of telescopes or with thirty types of spades for plowing, I do not exclaim “how beautiful.” Then there are also the museums of what used to be called the minor arts, in which case it is not enough to contemplate, one must be given the tools to contextualize and understand; but even for painting and sculpture, at least until the historical avant-gardes and in many ways until the 1960s, it is not possible to isolate the aesthetic component from the historical and cultural component. More complex and debated is the discourse if we shift to the art events of the last forty years, which have seen the gradual disintegration and dissolution of the phenomenal field of the arts, up to the postmodernism that has sanctioned the coexistence of all possible languages in a state of permanent chaos, certainly fascinating but which cannot be used to interpret the works of previous decades and centuries. The central issue is that the museum must be able to speak at the same time to different types of audiences, this can be done through the use of thematic routes inside the museum, with explanatory panels, with the use of all the new technological means we have today, but above all by distinguishing introductory rooms with an easy and essential historical path within the collections, then with thematic rooms that allow for in-depth study of, for example, a movement or an artist, and finally specialized rooms useful for scholars but also able to make the curious visitor perceive the complexity of history beyond museological simplifications. Within this scheme could find space for rooms with comparisons, such as those devised by Collu, perhaps to be renewed monthly. I do not want to deny that some comparisons between works from different times can be stimulating, but they cannot replace the entire historical framework of the museum. To make a comparison between Leopardi and Pirandello I must first be able to read and understand their works, then I can independently develop parallels; the same is true if I want to compare Canova and Mondrian. For works of art, too, we proceed in stages, starting with the alphabet of forms and techniques, moving on to phrases of style, then to the complete works of an author, then to the historical course of an era, and finally to comparisons between distant things. I heard several art historians who appreciated the new display for some of the suggestions, but when I retorted that our students, like part of the general public, are confused about what comes first between Michelangelo and Bernini they agreed with me that to make the comparisons one must already know art history. After all, this is not Collu’s idea; for her, the materials of the past are just a repository to be plundered to make new installations that reflect the curator’s ideas. One of the most glaring examples is the decision to dismantle what is perhaps the most important complex of Roman sculpture of the early 19th century, namely Canova’s Hercules and Lica with the procession of gods made by the major sculptors of the time for the destroyed Palazzo Torlonia. With great effort Sandra Pinto, thanks also to the studies of Stefano Susinno and others, had managed to reassemble the works in a unified way. Today they appear scattered each in a room with specious, sometimes ridiculous motives, used as fake petrified spectators looking at the paintings, imitating conceptual operations of famous artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto or Giulio Paolini, who, however, used worthless plaster casts not the original ancient statues. Although suggestive, this operation is contrary to the basics of preservation, which is concerned with protecting not only the materiality but also the nexuses of meaning in cultural heritage. The whole thing comes across as either foggy and inscrutable, or full of facilitation and naiveté, but it certainly does not correspond to the idea of democratization of the museum that is so much bandied about. The democratic museum is one that gives the opportunity to grow together, from children to the elderly, from those with disabilities to those doing literary studies, guiding the public by the hand with the different speeds and complexities of the paths; here instead we are faced with a self-referential elitism masquerading as the demagogic populism of the “museum for all,” as if the audience of Maria De Filippi’s programs and soccer games would be attracted by having put Canova between Penone and Pascali!

|

| On the wall, a painting by Ugo Rondinone on the left and Michelangelo Pistoletto’s The Visitors (1968) on the right. On the floor, Pino Pascali’s Bachi da bristola (1968). Photo by Luca Zuccala |

Let’s really talk about the audience. Even assuming that “Time is out of joint” succeeds in engaging the public better than previous installations, we can ask ourselves, also in view of the possible and thorny political implications of the issue, to what extent can the public be considered the protagonist and to what extent should the action of a museum management follow the tastes (or what it thinks are the tastes) of the public?

The basic premise is that there is no such thing as an audience as an indistinct whole, today the mass is liquid and mutant, there are many audiences, there is the lone visitor, the family with children, the small group of teenagers, the visit organized by the senior center, the art history majors accompanied by a lecturer, as well as the tour for participants in a meeting of heart surgeons or a busload of Japanese who know nothing about European history. The museum must be able to communicate with everyone, but in short, how do you talk to such distant types? The answer given by the new layout was: let’s mix it all up, let’s give a sense of light and clarity, let’s leave people free to wander around without pathways, without order, without panels, without captions about the contents, everyone will explain themselves, everyone will notice something, take a picture of something that struck them. It is a surrender in the face of complexity, to be inclusive one simply becomes banal, to speak to everyone one stutters first grade English: my name is Burri, Canova is on the floor, the white wall is beautiful. Incidentally, the title of the exhibition, which refers to a lucky line from Shakespeare, was left in English because, Collu says in the statement, the exhibition also unhinges translations, so much for inclusiveness. After all, the first hint of this state of confusion had come with the introduction of the new logo, which effectively changed the name of the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art to THE National Gallery, stop, with no other indication, with the article highlighted because they are the museum par excellence; a ridiculous thing that mimics the name of great foreign museums that are called only National Gallery, but without knowing that our history of museums has provided for the creation of numerous National Galleries as a legacy of the multifaceted geopolitics of the pre-unitary states and that in Rome were then distinguished the National Gallery of Ancient Art from the National Gallery of Modern Art; but why should the former Gnam be the only National Gallery and not Palazzo Barberini? In reality, it was later realized that what was at issue was not the prevarication of graphic designers but the desire to remove both the word art, which requires knowledge of meanings, and the chronological periodization concepts, while highly problematic, of modernity and contemporaneity. They also wanted to get rid of the ugly acronym Gnam, but then they created the Twitter account that uses the acronym Lagn, which strikes me as decidedly more repelling! Of course, my criticisms are about the layout and these theoretical statements, because then there are many good things, thanks to the excellent professionals who work in the Gallery and who continue to carry on important traditions of that institution, ranging from the reception to the didactics, from the workshops for children to the “Sundays at the Museum,” and then the presence on the web with the new website and the Facebook page, up to the new App for smartphones that allows you to get the information about certain works and artists by pointing your camera, although you have to go by trial and error, because in the captions there is neither a symbol nor a small number that makes it clear which ones have the card, which in any case does not refer to the placement of the work in the new “short-circuit” rooms. In spite of everything, Gnam remains an extraordinary museum because of the quantity and importance of its collections; however, we would like to be given the opportunity to see the works, especially the art of the nineteenth century, which today is diminished and humiliated by a function of comparison with the contemporary; if I place a battle by Fattori side by side with a plastic by Burri without any other comment, I can get two kinds of reactions: those who have older tastes will say “ah how they used to know how to paint, it seems true, I just don’t understand this contemporary art,” while those who have more avant-garde tastes will say “of course the abstract artists have done well to overcome all this boring resurgent painting.” These are two platitudes that I use as a paradox, but a museum director who brings out his visitors without having attempted to counter the platitudes and clichés has failed in his mission. Collu claims to want to be heterodox and subversive but the cliché to be demolished is not the art history textbook, if anything the problem is not knowing how to tell it in an exciting way. It’s too easy to “throw it away” as a colorful Roman expression goes.

|

| On the wall is Giuseppe Capogrossi’s Surface 512 (1963). The sculpture is a Reclining Figure by Henry Moore (1953). Photo by Luca Zuccala |

We anticipated that our society is undergoing significant changes: what were considered the reference points of our society have fallen apart, and as a result it is normal that art history also undergoes changes. This is not necessarily a bad thing, the important thing is that change does not become prevarication but opportunity: in this sense, what is the path you think the Gallery has taken? And finally: is there (and can the visitor use) an antidote against the postmodernism of “Time is out of joint”?

Let’s be clear, any reflection on the museum must start from the analysis, but also from the critique, of our time, otherwise the debate becomes sterile. In this sense, credit must be given to the director for reactivating a broad debate about a museum that was in danger of a certain marginalization. However, it is rather easy to get attention in media terms with a radical and scandalous operation, especially if one pursues a certain fury against everything that is considered old, from the cultural heritage officials who put the hateful constraints to the university professors who do not understand the tastes of the masses. In fact, I find it extremely serious that the arrangement of the previous director, Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli, made only a few years ago with the specific intention of making the chronological arrangement that Sandra Pinto had wanted easier and more evocative, has been cancelled without any effort of confrontation and mediation. Each director has the right to make his or her own imprint, but the museum is not his or her property, it is an asset of the citizens, those of yesterday and those of tomorrow, a certain continuity should be guaranteed to the history of the institution. On the other hand, that is, on the side of the historical-critical research carried out in the university, Collu has avoided even listening to the opinions of the museum’s scientific committee, an advisory body that has just been established and wanted by the same ministerial reform of museums; after the inauguration, two of the four members resigned (Iolanda Nigro Covre and Claudio Zambianchi), the other two (Fabio Benzi and Flavio Fergonzi) remained in office but the former wrote a harsh letter of dissent to the minister and the latter raised doubts publicly at a conference to which he had invited Collu. Now, if four out of four councilors express concerns, a director should ask himself some questions. Instead, as I was saying, today being criticized by professors becomes a kind of boast, just look at the level of barbarization of the current political debate. After all, the Gnam affair is not only a cultural issue but also a political one because it embodies all the contradictions of the reforms wanted by Minister Franceschini and other government reforms that have attacked the protection of cultural heritage without resistance from the competent minister. It is no coincidence that after the resignation of the two councilors, Pd deputy Lorenza Bonaccorsi promptly intervened to defend Collu from all those who oppose the “new” that triumphantly advances. Mine is not a criticism only of the Pd; on the contrary, it implies the observation that the cultural positions of the other political camps are equally close to the abyss. After all, the reform of the entire structure of cultural heritage has separated museums from the territory, leaving the capillary control of the widespread heritage and landscape increasingly unmanned and weak. The dramatic events of recent months, with the seismic tremors that have devastated central Italy, force us to repeat once again that the system of protection and knowledge of the territory should be strengthened, not debased. Here, I see in Gnam’s flattening toward a “Biennale model” a consequence of this philosophy. Many years ago Argan and Chiarante proposed for the cultural heritage a ministry united with scientific research and the university, instead they preferred to unite them with entertainment and today also with tourism. It is clear that in this view the problem is never the cognitive function of the museum, but the event, the suggestion, the sharing. Of course, these aspects are not negative, and many people will certainly like the new museum-exhibition, I am thinking especially of artists who prefer “hand-to-hand” with the works, perhaps even families who will come for a tour without the anguish of having to explain the history to their children. But it is only about the skin of the apple, there is a need to get to the pulp as well, because then the fruit-bearing seeds lie at the bottom. The museum takes a certain amount of effort and time, the public should not be frightened but neither should they be lazy. Today there are many systems to make fruition more compelling, for example, experiments in augmented reality are interesting, showing works in their original context or in relation to other things, combining multimedia and interactivity, to tell the many small stories that make up the big Story, but the prime example of augmented reality is the sensible juxtaposition of works in the same room, to do this you need a scientific project not the taste for provocation or the dart of the window dresser. The only antidote to the disintegration, fragmentation, liquidity, precariousness, of our time is slowness, reflection, internalization of the cognitive experience, if I leave the museum as I entered, my visit has served no purpose other than to peel off a ticket. Works from the past, even those from the very recent past that reach back to yesterday, tell stories, the further removed they are from our time or culture, the more they require listening, the search for threads of meaning that connect them to us. It is not a matter of actualizing everything; we need to understand and identify with the events, joys, dramas, and projects of past lives without making them speak with the voice of our time. When this happens we gain an enduring awareness of the temporal flux in which we are immersed and then perhaps, slowly, we will no longer feel so alienated in the prison of post-history but will be a speck helping to unravel, as Leopardi said, “the admirable and frightening arcane of universal existence.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.