Basel’s waterfront is home to an entirely... interactive museum: at the Tinguely Museum , young and old alike will enjoy seeing the peculiar mobile machinery sculptures created by one of Switzerland’s most innovative artists, Jean Tinguely (Fribourg, 1925 - Bern, 1991), move and turn and hear them play a few minutes after pressing the button corresponding to each...mechanical work. On the ground floor there is even a monumental sculpture on which the public can climb, walking through all its parts, like those constructions found at the playground with movable crossings, ladders and slides. At the same time, visitors will learn about the ingenuity and creativity of the metal sculptor to whom the museum is dedicated.

In fact, the world’s largest collection of Tinguely’s works is housed here, through which the 40-year history of his artistic career is traced. A pioneer of art in the second half of the twentieth century, the artist was very fascinated by the workings of machines, their movement and the noises that emanated from them. In particular, it was from 1954 that he intensified his work on moving automata and wire sculptures: working at a very fast pace he produced numerous groups of kinetic works and sculptures. He even invented interactive machines through which the public could create real works of art by themselves: his Méta-Matics were born in 1959 and challenged the classic relationship between artist, created work and viewer. At the Paris Biennial of the same year he presented Méta-Matic No. 1, powered by a gasoline engine: the machine moved freely in the dedicated space and produced drawings, but not only that: it gave off a scent of lily of the valley and inflated a large balloon until it burst. He was also able to create the first ever self-destructive work of art: consisting of the most disparate elements, including pipes, motors, bicycle parts, and radios, it was presented in 1960 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, under the title Homage to New York. After the Méta-Matics, Tinguely began to make (rather noisy) machines formed from scrap iron, and in connection with the latter, it is recalled that on the occasion of a Paris exhibition the artist transported his works, from the studio to the exhibition venue, organizing a kind of parade, in which his friends also participated. With the 1964Lausanne Expo, Tinguely began a new phase of his production: he began to paint his machines completely black. In general, from 1960 onward he produced projects that combined sculpture with architecture and at the same time were designed to provide entertainment for the public. He also began to give birth, from the second half of the 1970s, to Méta-harmonies, that is, large machines of motorized gears to which he added various musical instruments, especially percussion instruments; about the introduction of musical instruments, he emphasized that his devices did not make music, but rather used tones, played with tones. The Méta-harmonies mark the culmination of Tinguely’s interest in sound as an artistic medium. From the 1980s he then integrated animal bones and skulls into his machines: a way of addressing, through the ephemeral, his perennial struggle with death; the use of skulls was also joined by the use of consumer products and colored light sources in his last works of the 1980s. The theme of death would lead him to the creation of his last major work, the Dance of Death, composed of relics from a fire that had broken out on a farm in Neyruz, the artist’s hometown.

The Tinguely Museum traces all these phases of his production through drawings, sketches, Méta-mechanical sculptures, drawing machines, Méta-Matics, fragments of Homage to New York, radio sculptures, black-painted machines, designs for fountains, Méta-harmonies, and many other works.

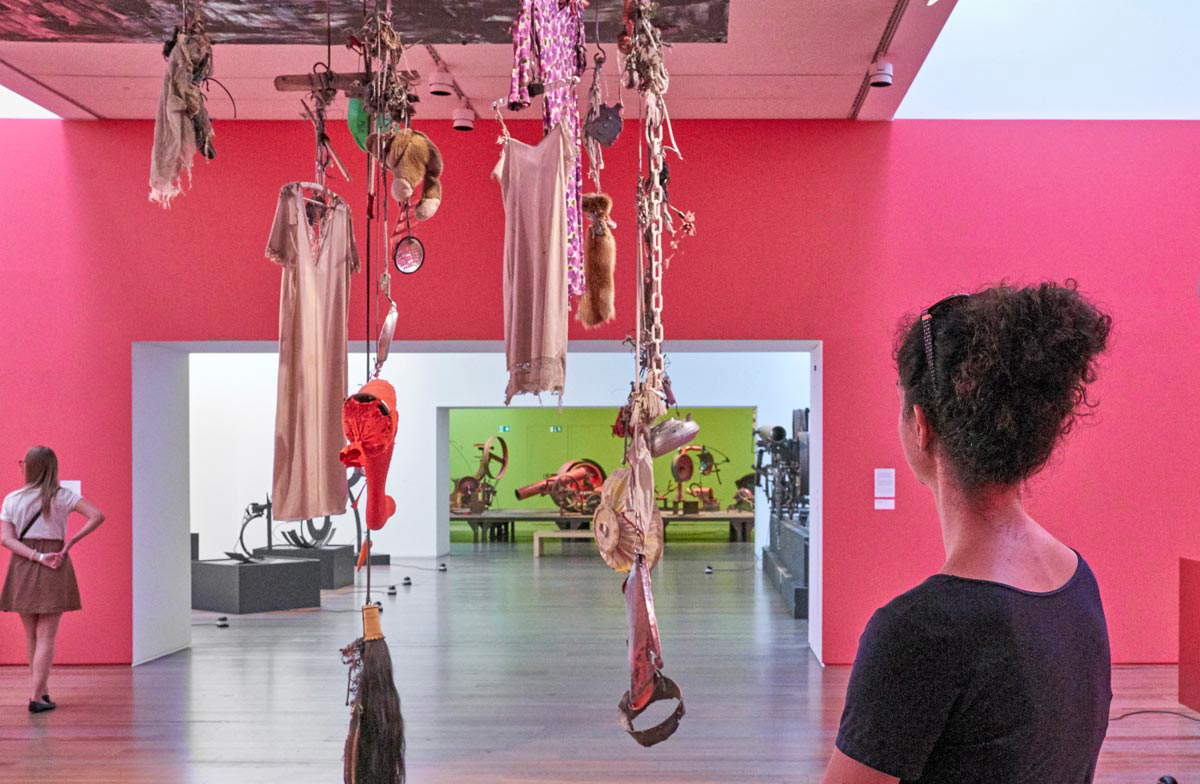

Especially striking are Ballet des pauvres (ballet for the poor) from 1961: from the ceiling hang on wires and elastic bands defective and discarded objects from everyday life, such as a nightgown, a broken kettle, a fox fur, a tray. Operated by a timer, all these items suddenly begin to shake in front of the viewer, who is also amazed by the loud clanking noise caused by the collision of the metal objects. With a surprise effect. Le Plateau agriculturel, 1978, also promotes an interaction between individual parts for an evocative overall effect: it is composed of parts of farm machinery, red in color, scrap iron, and garden gnomes; in addition to the mechanical noises, the viewer has the impression of witnessing a stage scene, in which work, dance, and theater are intertwined. The Fatamorgana (1985) is a Méta-harmonia, a large machinery of gears formed by tall frames on which Tinguely mounts old wheels, from the largest to the smallest, with various objects, percussion instruments and a cowbell in between. One can easily imagine what sound he produces when he sets everything in motion. Finally, the aforementioned Méta-harmony on which visitors can climb, in a real path with stairs, slides, etc.: this is the Méta-Maxi-Maxi-Utopia (1987) and was created in line with the obsessive drive to bring whole worlds of machines to life for peaceful and cheerful coexistence with people. Regarding this work, Tinguely had said in an interview, “I want to create something fun, something for children to climb and jump on [...] Something with entrances, lots of entrances, exits and passages, and that you can go through it from above and below [... ] I want everyone to forget that it is a sculpture: the main thing for me is that it entertains the visitor, so that the visitor feels at home.”

|

| Tinguely Museum, permanent collection room. Ph. Credit Daniel Spehr |

|

| Tinguely Museum, permanent collection room. Ph. Credit Daniel Spehr |

Two exhibition projects are now underway at the Tinguely Museum that mesh well with some of the works in the permanent collection of the Basel museum venue.

The Pedro ReyesReturnto Sender exhibition is on view until November 15, 2020. Curated by director Roland Wetzel, this is the fifth in a series of exhibition projects that focuses on particular aspects of Tinguely’s Dance of Death (in 2017 Jér>ôme Zonder focused on the critique of totalitarianism; in 2018 Gauri Gill focused on the Memento Mori ’s concept of vanitas between birth and death; in 2019 Lois Weinberger initiated a comparison of superstition and Catholicism; and Tadeusz Kantor’s Dance of Death and Theater of Death were compared with Tinguely’s work of the same name).

For the current exhibition, Pedro Reyes created a new work based on his previous work from 2012: for the Disarm series of works, the artist used 6700 weapons confiscated in the Mexican drug fight and turned them into musical instruments. In a first version, he made instruments that could even be played live by his musician friends; this was followed by Disarm (Mechanized I) in 2012-13 and Disarm (Mechanized II) in 2014 consisting of the union of multiple parts of weapons and instruments, capable of playing mechanized and automated percussive musical pieces.

The second of the two versions of Disarm (Mechanized) is placed in dialogue with Tinguely’s Dance of Death, installed in an almost sacred-looking room recently set up in the museum in 2017. In the nearby rooms, Tinguely’s critique of totalitarianism and Reyes’s critical examination of the socially destructive exchange processes of drugs and weapons are linked in a tragic dance of death.

In 2007, Reyes attracted international attention with his project Palas por Pistolas, working with local authorities in Culiac>án, Mexico, for the purpose of exchanging weapons owned by the population for vouchers for household appliances and appliances. The weapons were melted down and turned into 1527 shovels to be used to plant the same number of trees. Parallel to the Return to Sender exhibition, this project continues in front of the entrance to the Tinguely Museum with the planting of a chestnut tree. Both Disarm and Palas por Pistolas are thus projects that originated in the specific context of the Mexican drug fight. With his new work Disarm Music Box (2020), Reyes once again draws attention to the commercialization and spread of weapons: from a pacifist perspective, the artist criticizes the ever-increasing increase of weapons in the world by turning them into music boxes. Weapons made by manufacturers in almost every country in the world are withdrawn and destroyed in order to create, from the barrels of the weapons, sound bodies that are then inserted into new music boxes. The latter also play famous pieces of classical music that characterize the weapons manufacturers’ countries of origin: Mozart’s song is played by a music box with Glock gun parts, Vivaldi with Beretta barrels, and songs by Swiss singer-songwriter Mani Matter come out of a music box with rifles. The artist’s aim is to recycle, to transform an instrument of death into a musical instrument, a symbol of dialogue and exchange. “Weapons embody the rule of fear, while music embodies the rule of trust: both involve creativity and technology, but one aims to suppress others, the other is a form of liberation. These sculptural works are not only meant to transform matter, but also to provoke a psychological transformation and, hopefully, a transformation of society as well,” the artist stressed when speaking about his exhibited works.

In his artistic production, Pedro Reyes has used various art forms, from architecture to sculpture, from video to performance, to address political, social, ecological and educational issues.

|

| Pedro Reyes, Disarm Music Box ( Glock/Mozart), Disarm Music Box ( Beretta/Vivaldi), Disarm Music Box (Karabiner/Matter) (2020; installation). Copyright Museum Tinguely, Basel. Ph. Credit Daniel Spehr, Courtesy the artist. |

|

| Pedro Reyes, Disarm (Mechanized) II (2014; installation). Copyright Museum Tinguely, Basel. Ph. Credit Daniel Spehr, Courtesy the artist. |

In addition to Pedro Reyes’ exhibition, a major exhibition dedicated toJapanese artist Taro Izumi is open to the public. An artist who has been able to create a unique universe, where sculpture, video, installation, and performance come together in a true ecosystem, which continuously transforms. A sculpture can become an installation that in turn serves as a backdrop for a performance that can be viewed on numerous screens. To create his works, Izumi uses wood, textiles, plants, furs, furniture and all kinds of recycled elements, and combines them to create structures that at first glance appear to be made up of elements in bulk, but are actually arranged with precision and logic. The world of Izumi, a master of opposites, is playful and entertaining as he introduces the absurd into his works.

At the Museum, Tinguely presents a path full of optical illusions and mirages: a theater without an audience, invisible works, robots floating in the air. The artist makes often surreal pairings of objects that are opposed to each other, and their meaning sometimes remains mysterious. These objects represent the absurdities of everyday life and tell of the chaos of today’s world.

Symbolic of the spirit of the absurd that runs through Taro Izumi’s art is the Tickled in a dream...maybe? series: these are interlocking sculptures and videos that form structures composed of common elements, such as chairs, tables, stools, and cushions, that are intended to reproduce a particular position of a moving body. Each structure is accompanied by photographs of athletes, especially soccer players, immortalized in acrobatic actions. These particular “architectural” structures are intended to recall, in design and concept, Tinguely’s interactive works and his playful spirit.

Starting from the premise that theaters around the world were closed during the health emergency, the artist created asound installation composed of white noise, collecting the sounds of empty theaters around the world. This silence, vibrating in unison, becomes a tangible, if extremely small, trace.

Visitors will also find sixteen billiard balls of sixteen different colors scattered throughout the exhibition. These, however, do not move, do not roll, but are trapped and enclosed in narrow boxes of transparent plexiglass, to reflect the feeling of isolation from the world, of being as if in a transparent glass where one can see everything but is forced to remain motionless. A feeling the world experienced during the pandemic.

For more information about the museum, Jean Tinguely and temporary exhibitions: tinguely.ch

|

| Taro Izumi, Cloud (pillow/raised-floor storehouse); Cloud (goodbye) (2020; installation). Copyright Museum Tinguely, Basel. Ph. Credit Gina Folly |

|

| Taro Izumi, Tickled in a dream...maybe? (The cloud fell) (2017; installation). Copyright Museum Tinguely, Basel. Ph. Credit Gina Folly |

|

| Works interact with the public at the Tinguely Museum in Basel |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.