Transavantgarde art takes center stage in Estonia: in fact, from December 1, 2023 to May 19, 2024, Tallinn ’s KUMU is hosting the largest exhibition ever dedicated in the Baltic regions to the Italian movement of the 1980s, which had great international success. The exhibition, entitled Borderless Universe in Their Minds: Italian Transavantgarde and Estonian Calm Expressionism, is curated by Sirje Helme, director general of the Estonian Museums Foundation, and Fabio Cavallucci, former director of the Luigi Pecci Center for Contemporary Art and the Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. The five protagonists of the Italian movement, namely Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Nicola De Maria, and Mimmo Paladino, are compared with the two major exponents of the Estonian group Rühm T (an important movement that arose in Estonia in the 1980s, thus contemporary with the Transavanguardia), Raoul Kurvitz and Urmas Muru.

It was 1979 when Achille Bonito Oliva published the first article on Transavanguardia in Flash Art magazine, opening a route that would soon be taken by numerous artists around the world. The Zeitgeist was manifesting itself in a return to traditional painting and art techniques, in opposition to the now repetitive conceptual Esperanto, to the idea of art seen only as continuous linguistic progress. The Transavantgarde and parallel movements that developed somewhat around the world sensed that the past could also be fertile spheres of work, initiating a cultural nomadism that allowed them to take up styles independently of their original meaning, mix them, use them for their own ends.

However, these were years when the Soviet bloc continued to be virtually unknown to the West culturally. And even artists living beyond the curtain struggled to get information about Western artistic developments. A 1982 text by Bonito Oliva, The International Transavantgarde, recorded far and wide the blossoming of the new painting, from Italy to Germany, from France to Britain, from North America to South America, but it did not even touch on the Soviet Union, let alone Estonia, which for the West at that time just did not exist. Estonia would appear on the maps along with the other Baltic states only after 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union and newfound independence. And in Estonia, the 1980s were a particularly difficult time because of Soviet censorship control: cultural information was barely leaking out, perhaps through a few magazines that arrived clandestinely. So it would be a few years before that individualistic spirit of total freedom to move among styles penetrated there as well. It would be necessary to wait until 1986 for a neo-expressionist style of painting to have its own moment of visibility, precisely through the Rühm T group and its main protagonists, Raoul Kurvitz and Urmas Muru, precisely.

What do Transavanguardia and Rühm T artists have in common? First, a powerful expressionist painting free of rules. Then above all, the ability to create their own “personal mythology.” Says Sirje Helme, curator of the exhibition together with Fabio Cavallucci: “Unlike mythology in its historical meaning, personal mythology is not based on folklore nor does it claim to hold any merit of truth or normative classificatory function. Personal mythology is a description of the author’s worldview, an important element of which is spatial and temporal ambiguity and the opportunity for the artist to create his or her own subjective space, to engage in his or her own inner world and fantasies. The emphasis on subjectivity allowed for the disregard of previously implicitly accepted norms as well as criticism of the official cultural line.” And herein lies precisely one of the main points of the comparison between the two movements, according to the curators: while the Italian Transavanguardia is often seen as an apolitical movement, if not outright reactionary with respect to the earlier anf years of engagement, Rühm T, by focusing on subjectivity, gave a signal of opposition to implicitly accepted norms, thus initiating a cultural critique that to some degree was also political.

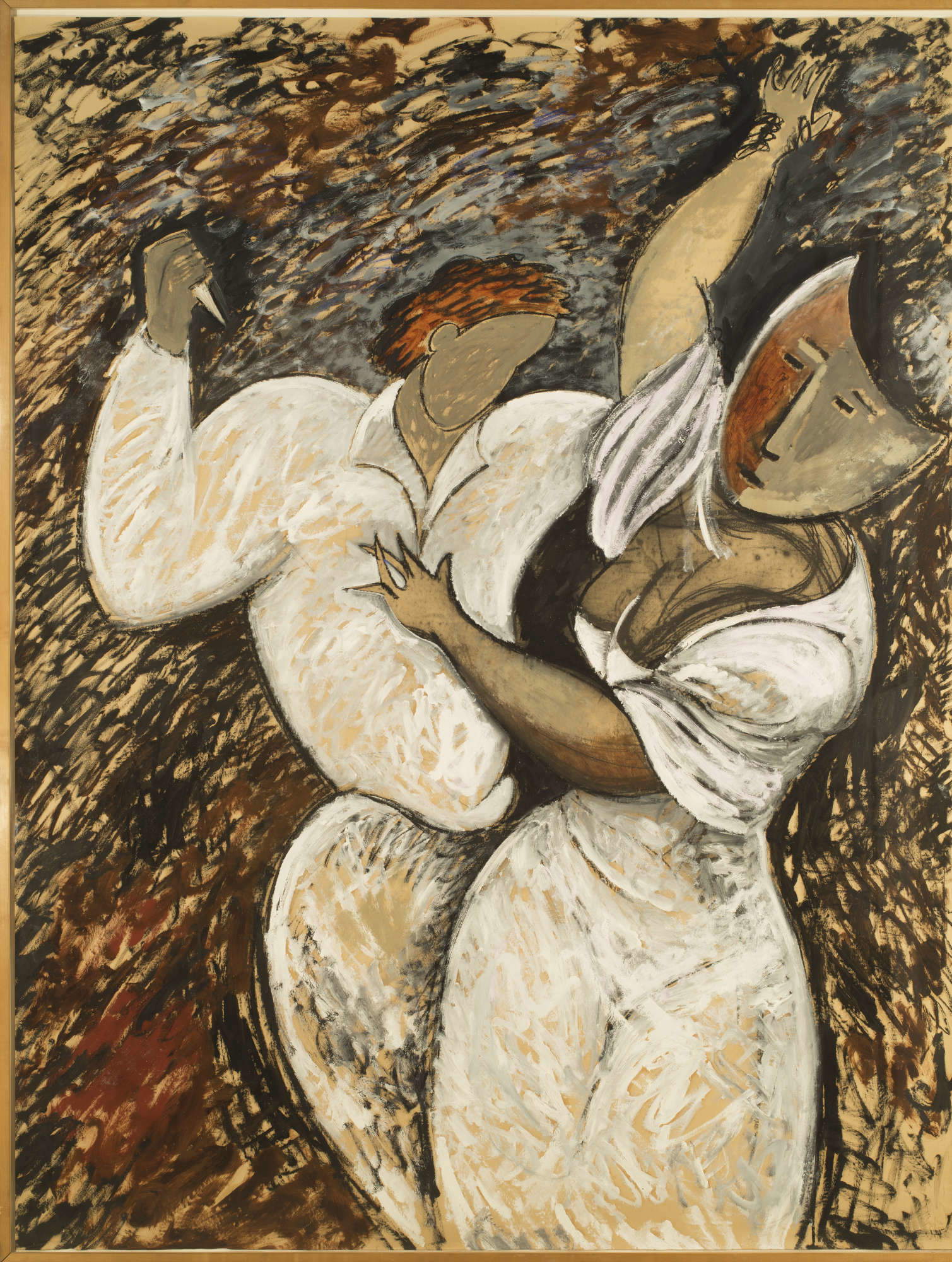

Among the Italian works on display are a number of masterpieces, mainly from the 1970s and 1980s, the golden years of the Transavantgarde, lent by private collectors (the vast D’Ercole collection in Rome), private galleries (Claudio Poleschi Arte Contemporanea in San Marino), public museums (Mart) and also by the artists. Among the works on display areSilent. Mi ritiro a dipingere un quadro (1977) by Mimmo Paladino, which marks as a turning point in the return to painting; La rastrellatrice (1979) by Sandro Chia; Non vuoto (1979) by Francesco Clemente; Musica ebbra (1982) by Enzo Cucchi; and Il regno dei fiori (1984-85) by Nicola De Maria.

In addition to Kurvitz’s and Muru’s works, examples of the coeval productions of German neo-expressionists, such as Baselitz, Kiefer, Lüpertz, and A. R. Penck, from private collections also complete the exhibition. Finally, there is ample documentation, including, for the Italian side, numerous speeches by Achille Bonito Oliva produced by RAI and a recent interview by Estonian National Television.

|

| Transavantgarde in Estonia: an exhibition on the Italian movement in Tallinn |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.