The Savoy told by 270 postcards: history and propaganda at the Palazzina di Caccia di Stupinigi

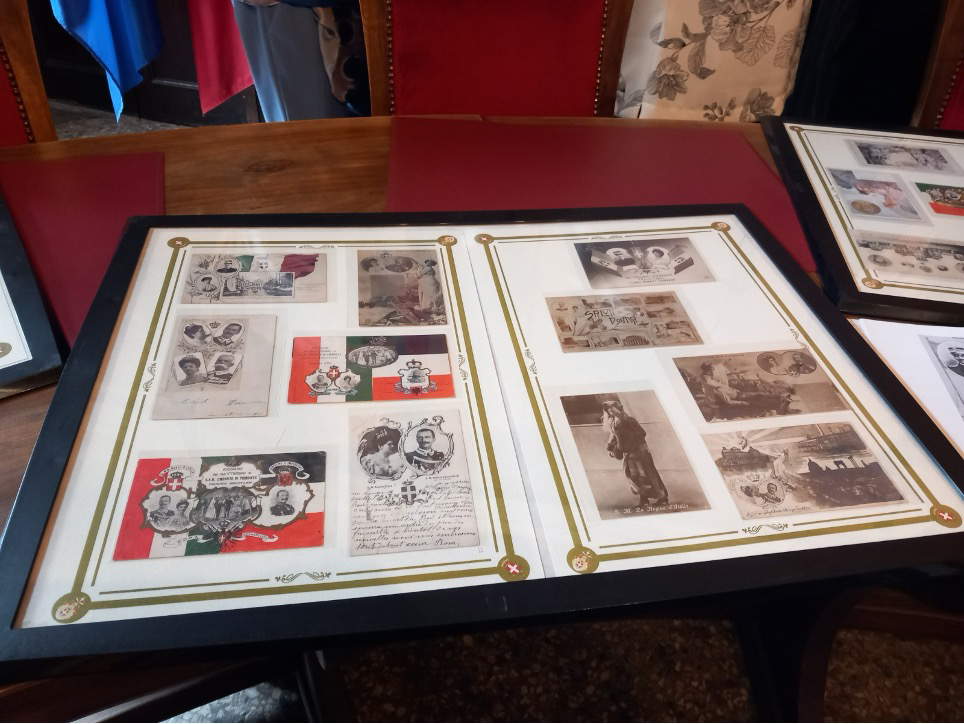

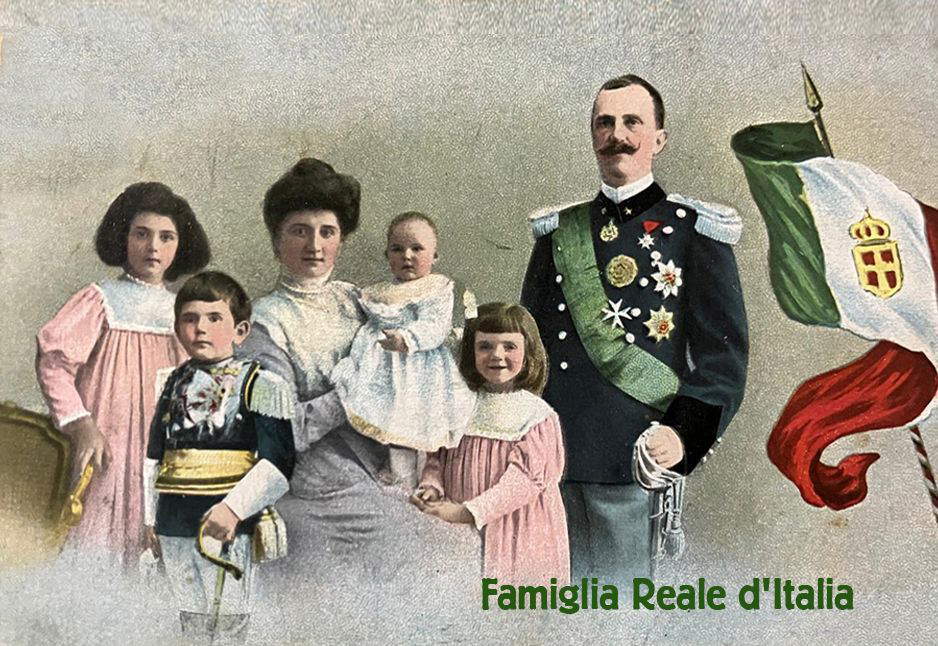

The postcard has been more than just a means of communication: it has been a tool for propaganda, information and even political satire. Recounting the function of postcards will be the exhibition The Savoy in Postcards, 1900 to 1915, held from March 4 to April 6, 2025 at the Palazzina di Caccia in Stupinigi, in the historicEast Corridor. The exhibition brings together 270 illustrated postcards documenting the early part of the 20th century, including diplomatic meetings, political events and military conflicts, with a focus on the figure of Victor Emmanuel III and the international context.

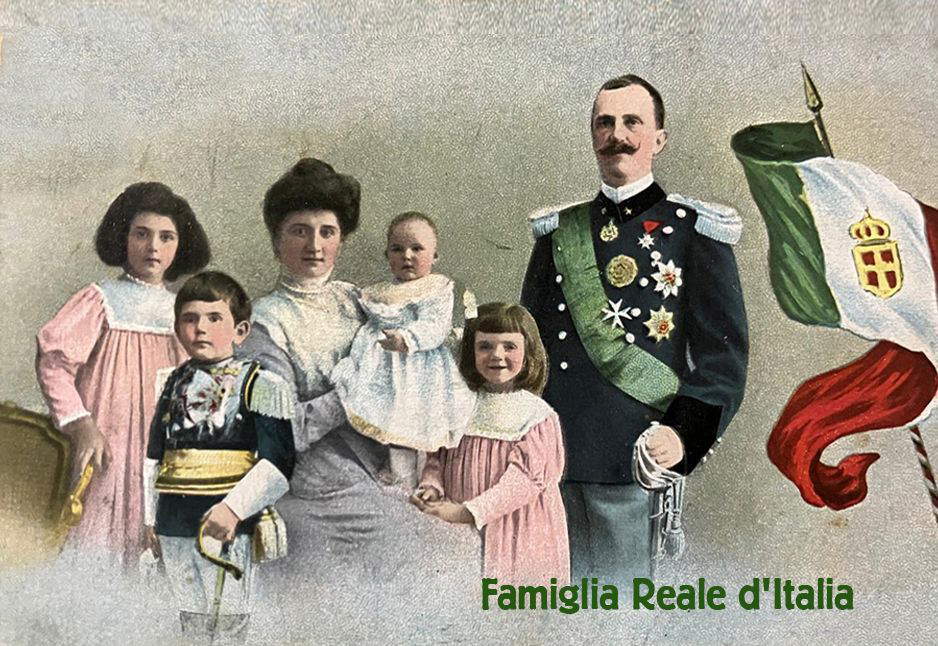

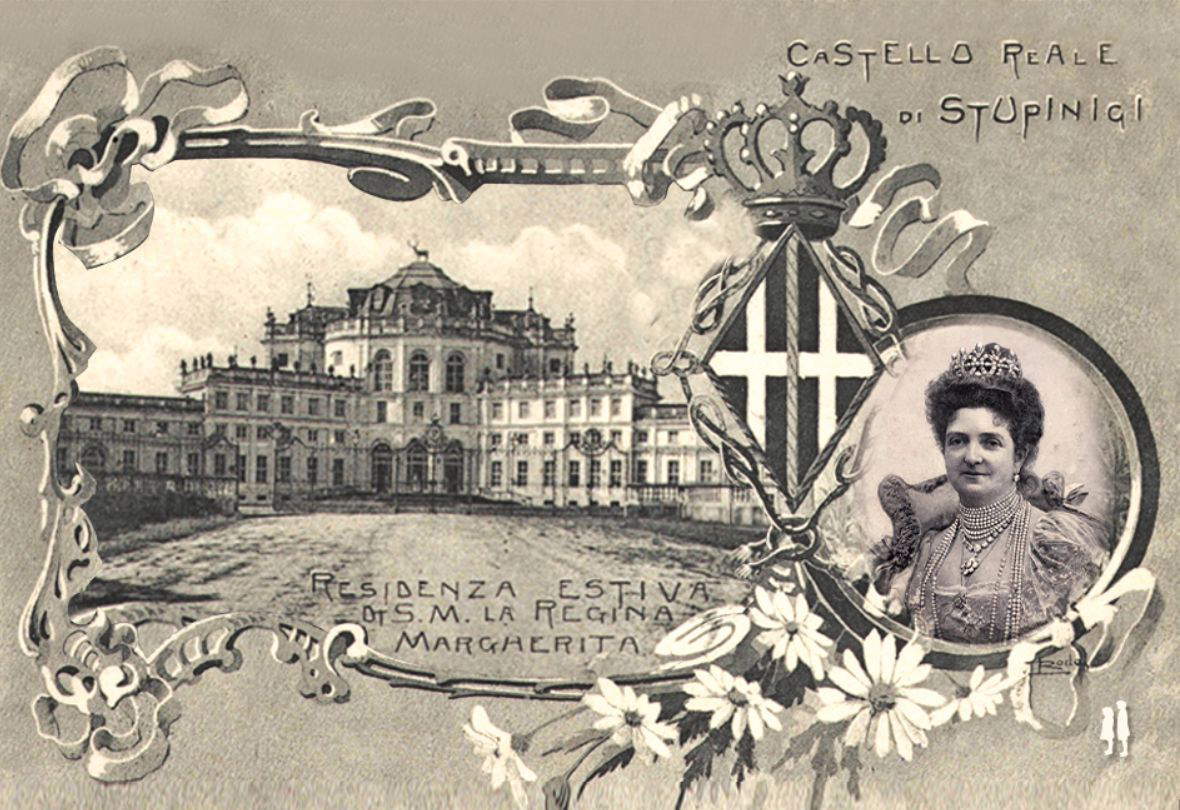

Postcards from the Kingdom of Italy offer a significant cross-section of the period, illustrating key moments of the Savoy monarchy. They range from the sovereign’s first official visits to meetings with President Émile Loubet of the French Republic, Edward VII of England and Tsar Nicholas II, to the years of the Italo-Turkish War. Austro-German postal propaganda often depicted Emperors Franz Joseph and Wilhelm II next to Victor Emmanuel III’s profile, while satire did not spare the king in the months between 1914 and 1915, when he decided not to enter the war immediately on the side of the Triple Alliance, a side he himself had never really supported. The images and messages conveyed by postcards testify to the crucial role of this medium in an era of great change. Their dissemination marked an evolution in the way political and social realities of the time were informed and represented.

From the birth of the postcard to its artistic revolution

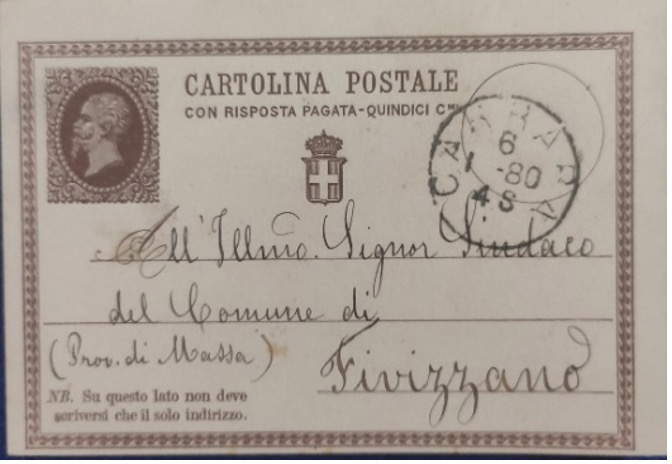

The idea of the prepaid postcard was proposed in 1865 by Prussian Postal Councillor Heinrich von Stephan, who intended to simplify the postal system by allowing short messages to be sent without having to purchase an envelope and stamp separately. However, the Prussian government rejected the project, deeming it immoral to send mail without protection. The idea was taken up by Austrian Emanuel Hermann, a professor at the Teresian military academy, who promoted its adoption by the Vienna Post Office. On September 25, 1869, thanks to the intervention of Baron Od-Maly, director of the Austrian Post Office, the postcard became a reality.

In Italy, the new format was introduced in 1873 with Decree Law No. 1,442. In January of the following year, Italians also began sending postcards, adhering to a custom that would soon spread throughout the world. The most significant innovation came when the writing portion was replaced by pictures, transforming the postcard into a vehicle for visual communication. The publisher Danesi was among the first to print illustrated postcards in black and white, creating a format similar to the covers of weekly magazines at the time. The real success, however, came with color postcards, which began to represent events of great historical significance. In Italy, the first moment of wide circulation occurred on the occasion of the wedding between the Prince of Naples, Victor Emmanuel, and Princess Elena of Montenegro, celebrated on October 24, 1896.

Through the collection one can observe the image of the sovereign in various official situations, including diplomatic visits and institutional celebrations. The postcard’s use in wartime propaganda and public opinion movements is also highlighted, with illustrations extolling the alliance with Austria and Germany or, conversely, satires bashing the monarch in the months of Italian neutrality before he entered World War I. In addition to the political and propaganda aspect, the exhibition offers a reflection on the postcard’s artistic evolution. Early monochrome illustrations gradually gave way to increasingly detailed and evocative images that captured salient moments in Italian history.

Practical information

Rates:

12€ for full ticket

8€ for reduced.

Admission will be free for children under the age of 6.

|

| The Savoy told by 270 postcards: history and propaganda at the Palazzina di Caccia di Stupinigi |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.