An exhibition to reread a particular season of postwar Italian art: La forza del vero. The Modern Painters of Reality, at the Mart in Rovereto from May 15 to September 18, 2022, tells the public about the adventure of the “modern painters of reality,” who between 1947 and 1949 lashed out against the outcomes of modernism and the “blunders” of the École de Paris, in defense of the great pictorial tradition. The group consisted of Gregorio Sciltian, Pietro Annigoni, Antonio and Xavier Bueno who were later joined by Giovanni Acci, Carlo Guarienti and Alfredo Serri. Seventy years after the conclusion of this brief and controversial experience, the Mart reconstructs an artistic event that represents an ideal continuation of the climate of Valori Plastici and that of Magic Realism, with an exhibition curated by Beatrice Avanzi, Daniela Ferrari and Stefano Sbarbaro.

At the end of 1947 the nascent group of Modern Reality Painters mounted an exhibition in the gallery of the magazine L’Illustrazione Italiana, in Milan’s Via della Spiga. The exhibition is accompanied by a pamphlet-manifesto signed by four of the artists present: the eldest is Gregorio Sciltian (Nakhichevan-on-Don, 1900 - Rome, 1985), a Russian painter of Armenian origin active in Milan. With him are Milanese Pietro Annigoni (Milan, 1910 - Florence, 1988) and Spanish-born brothers Xavier Bueno (Bera, 1915 - Fiesole, 1979) and Antonio Bueno (Berlin, 1918 - Fiesole, 1984), all three based in Florence. The exhibition also features Carlo Guarienti (Treviso, 1923), also based in Florence, and the Florentines Alfredo Serri (Florence, 1898 - 1972) and Giovanni Acci (Florence, 1910 - Pietrasanta, 1979).

Within two years, the Modern Reality Painters would hold four more exhibitions, in Florence, Rome, again Milan and Modena. Although appreciated by the public (there is talk of twenty thousand visitors in fifteen days for the first Milan stop), collectors and several artists, they are disapproved by critics who, misunderstanding their intentions as curator Sbarbaro explains in the catalog, accuse them of “passatism, photographic oleography and an empty seventeenth-century virtuosity far from the poetics of realism.” Moreover, their ideological positions are decidedly heterogeneous: the Bueno antifranchists, enrolled as young men in the Swiss Communist Party, Annigoni avowedly anti-fascist, Sciltian an anti-Bolshevik who fled Russia. On the contrary, what unites the Painters is the desire for a rebirth of painting that corresponds to a parallel rebirth of humanity after the destruction, deprivation and suffering of the recent world conflict. In the search for pure, real and therefore eternal artistic virtues, there is the desire for absolute moral and spiritual values, the aspiration for that authenticity which they believe can be duly traced only in “true painting.” The four claim a “moral painting in its intimate essence,” an ideological horizon that they do not believe belongs to artistic pursuits that deny the real datum. In the manifesto signed in 1947, Sciltian, Annigoni and the Bueno brothers take a stand against the outcomes of modernism and the “blunders” of the École de Paris; they condemn the avant-garde and the nascent abstractionism to which they prefer the great Italian painting tradition. Decisive in the formulation of what is an artistic and cultural challenge is the contribution of Giorgio de Chirico, who has established relationships of esteem with all four artists.

The Modern Painters of Reality lashes out harshly against the decadent artistic expressions of many contemporaries, manifestations of the prevailing regression and ruin. They counterpose these languages with an evocation of ancient and higher stylistic models from the past. However, despite declaring intentions of fraternity, universality and neutrality, beyond assertions about an art within the reach of all, the Painters betray a polemical attitude that seems to disapprove of at least half a century of painting, and that struggles to find theoretical correspondence in the socio-cultural context of the time. The art world marginalizes and harshly rejects their demands, which are not totally understood and are considered radical and anachronistic. Submerged by criticism, the group disintegrates mainly because of its inherent and remarkable heterogeneity: ideological distances, cultural incompatibilities, and anagraphical differences shortly lead to the end of a remarkable and original artistic experience.

More than seventy years later, the Mart in Rovereto reconstructs the complexity of the Modern Painters of Reality. In fact, the exhibition The Force of Re ality seeks to underscore the commonality of purpose that united the seven artists. Through undoubtedly personal paths, Acci, Annigoni, Antonio Bueno, Xavier, Bueno, Guarienti, Sciltian and Serri reappropriated, as Sbarbaro explains in his essay in the catalog, the pictorial models offered by the old masters and found “a point of convergence in the formulation of a cultured and refined painting, rich in references and quotations not only of a formal nature.” The exhibition also aims to further research the careers of individual artists, already known to scholars for their richness and complexity, and to reconstruct their significant parabola within the history of 20th-century Italian art.

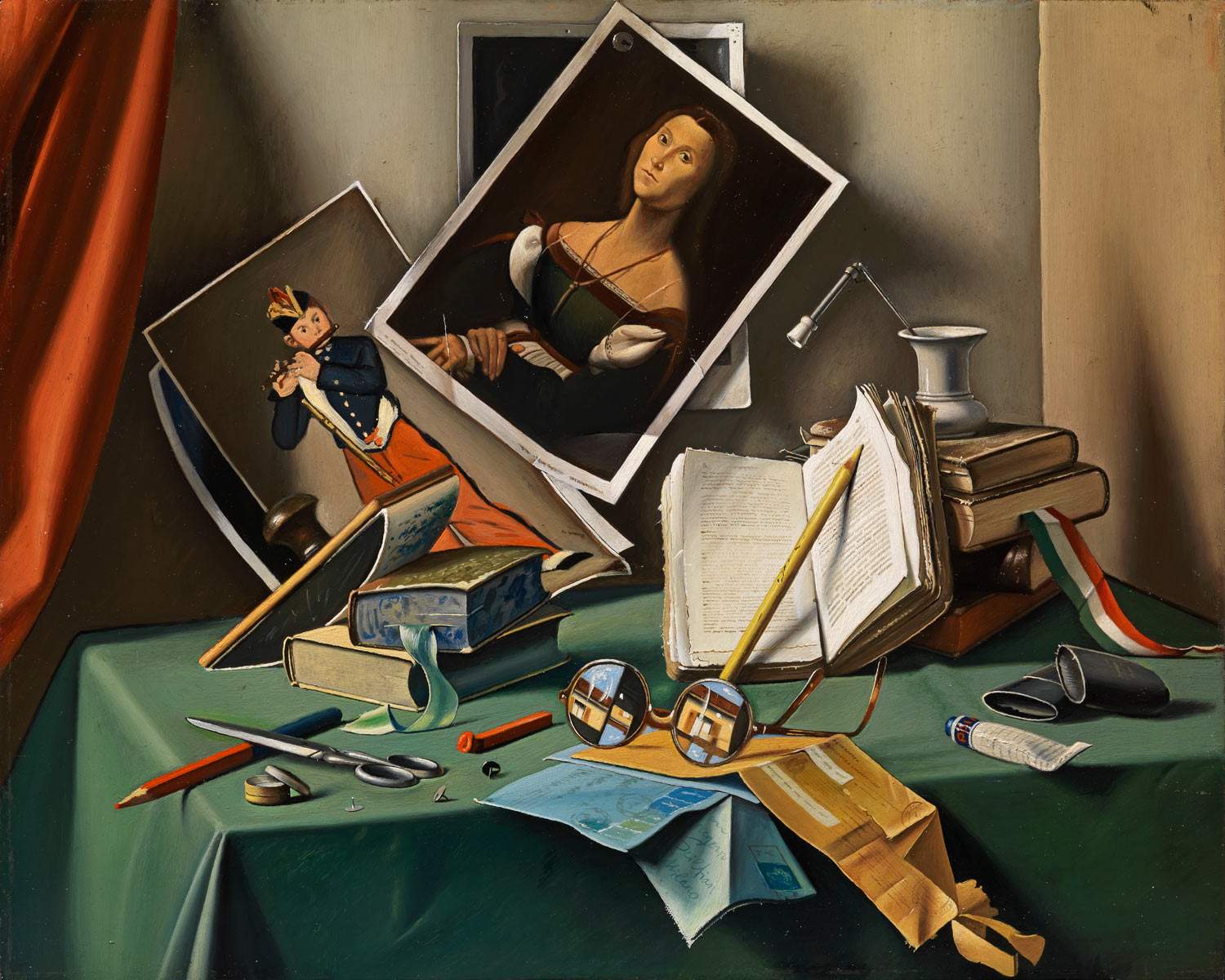

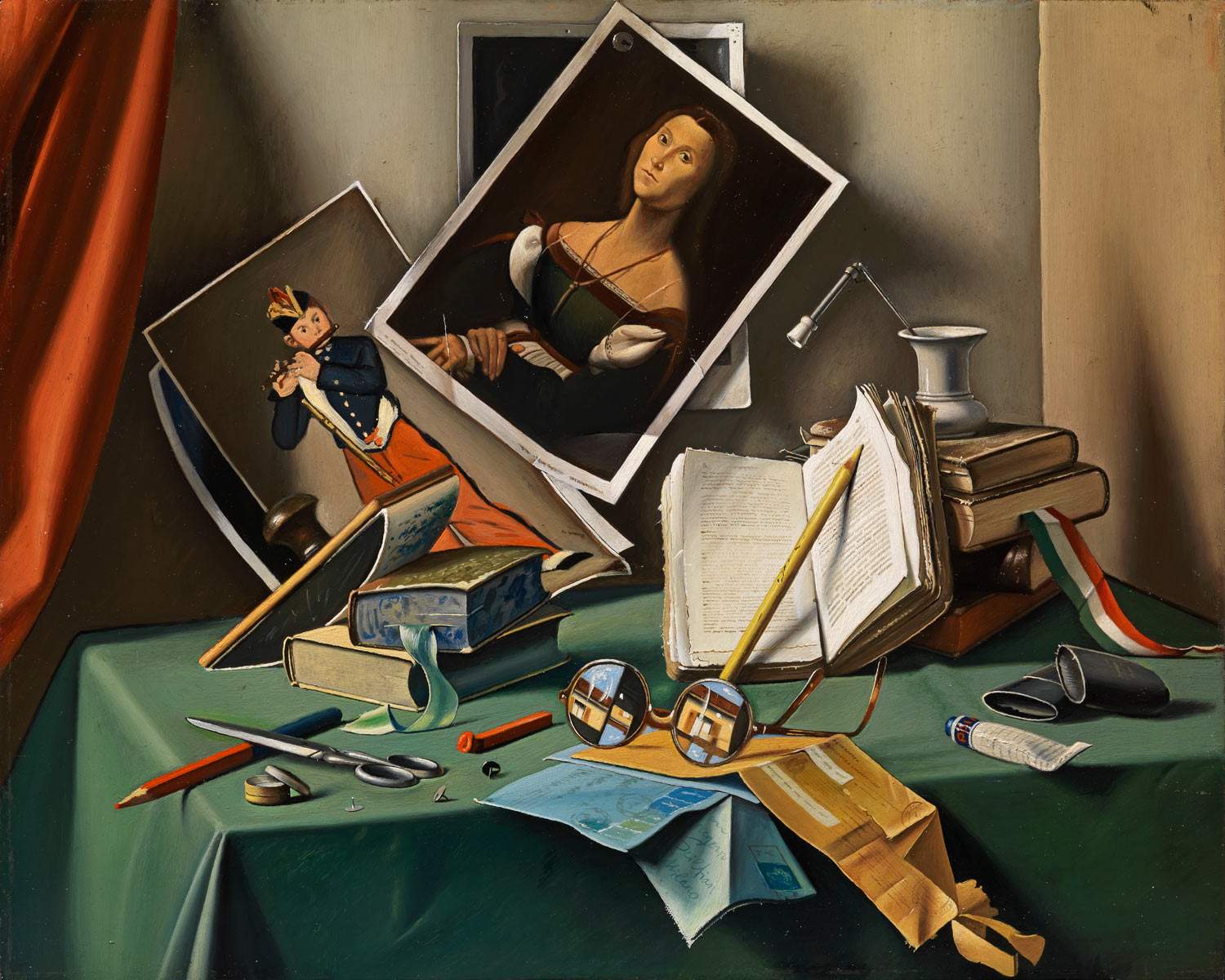

The review is divided into five sections. After a brief introduction in which the four signatories of the Modern Painters of Reality manifesto are presented, we move on to the first section, devoted to Gregorio Sciltian. The Russian-born artist arrived in Italy in the early 1920s and made his debut with a solo exhibition at the Casa d’Arte Bragaglia in Rome (1925) presented in the catalog by Roberto Longhi. The eminent critic recognized in his painting obvious echoes of Caravaggio and a meticulous rendering of details reminiscent of that of Flemish and Spanish still lifes: important references for the young artist who had already admired Caravaggio’s Madonna of the Rosary during his studies in Vienna after leaving Russia following the October Revolution. Sciltian is part of the process of rediscovery of Caravaggio’s painting that began in 1922 with the Exhibition of Italian Painting of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, held at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. If his first paintings made in Italy, such as the Portrait of the Futurist painter Ivo Pannaggi or The Self-Portrait with the Bianchi Family (1925), testify to his singular mediation between the German New Objectivity German and Magical Realism, there also emerges a chromatic sensibility of seventeenth-century ancestry(The Man Combing His Hair, 1925) that would later be accompanied by conscious references to the painting of Caravaggio and Velázquez(Bacchus in the Tavern, 1936). His still lifes become, over time, increasingly crowded with objects and rich in detail, with a trompe-l’oeil effect that achieves the “illusion of reality” pursued by the artist. Among these works is also a tribute to Roberto Longhi, where we see reproductions of a painting by Manet (among the first artists to rediscover seventeenth-century Spanish painting) and Raphael’s famous Muta, as well as spectacles that remind us of the keen powers of observation of the famous art historian: the one who recognized in Sciltian the first Caravaggesque of the twentieth century.

The second section delves instead into Pietro Annigoni, who oriented his research on the primacy of drawing according to the model of the Tuscan school, engaging in a personal challenge with the artists of the past. Having moved with his family to Florence from Lombardy, Annigoni decided to continue his artistic studies in the Tuscan capital even after his engineer father was called back to Milan, and he approached the painting of the Renaissance masters, delving into the use of ancient techniques such as tempera grassa, fresco and engraving. As early as 1932 he forged a lasting bond with another artist who would join, like him, the Modern Painters of Reality, Alfredo Serri. Although a decade older, Serri was his pupil and fraternal friend, as well as a tireless animator of the lively bohemian climate that characterized Annigoni’s studio in Santa Croce, as seen in the Self-portrait of 1936. The portraits and self-portraits confront, too, a great pictorial tradition, from the Northern Renaissance to Théodore Gericault’s Cycle of the Alienated, to which Annigoni seems to refer with his Cinciarda (1942), a doctor who poses for him on more than one occasion, and with La vecchia del cardo (1941): works that reflect the somber climate of the war years.

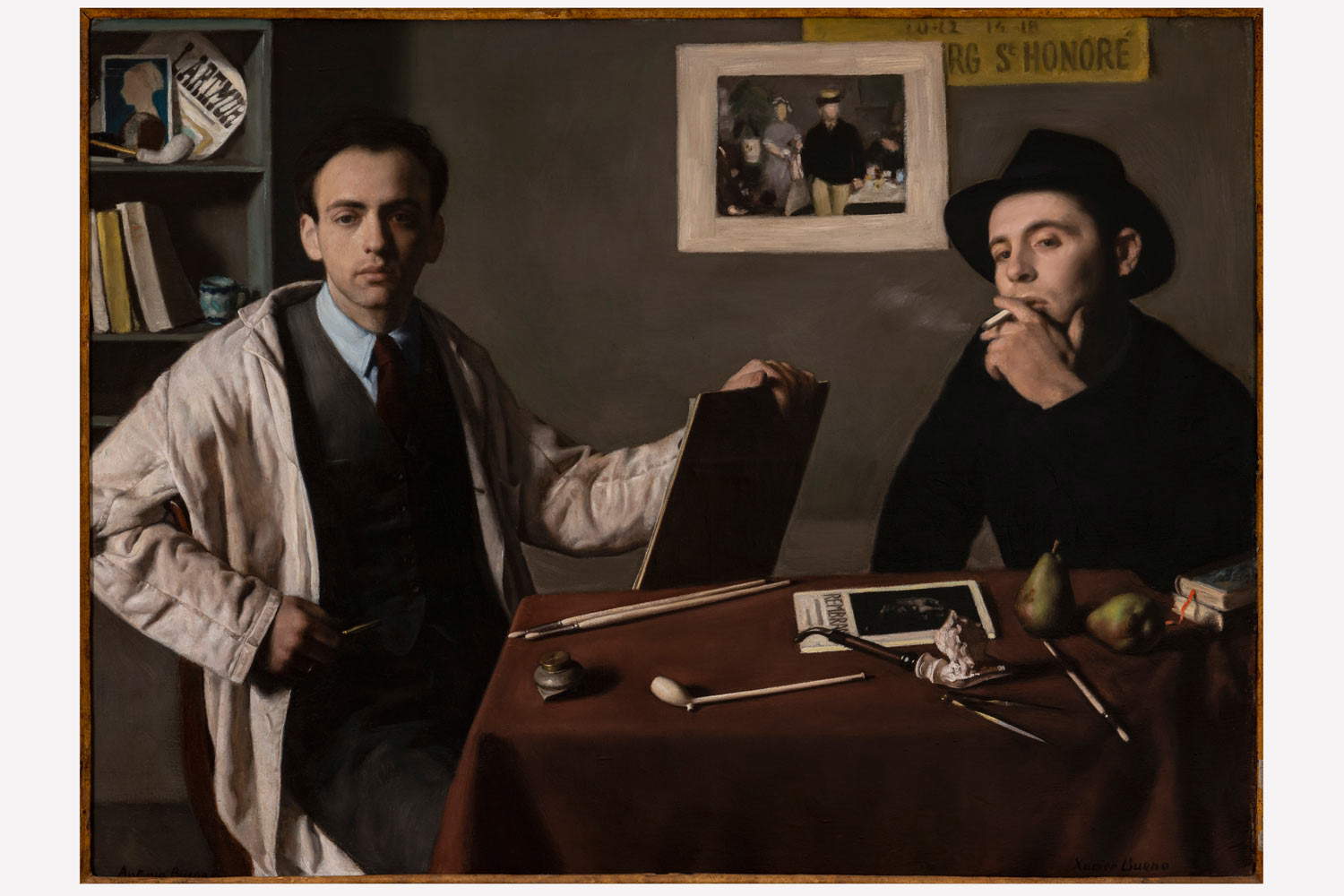

We then move on to the section on the Bueno brothers, who arrive in Florence in January 1940 for a study trip and remain there because of Italy’s entry into the war. Here they befriended Pietro Annigoni, who in 1942 helped them with their first exhibition at the Ranzini Gallery in Milan. The talent and extraordinary mastery of painting techniques of the two Spanish brothers did not go unnoticed, and soon their work was appreciated by Gregorio Sciltian and Giorgio de Chirico. Since 1938, when Antonio had joined his older brother in Paris, an intense artistic partnership had begun that for the next ten years intertwined the biographical and professional fortunes of the Bueno brothers. Evidence of this can be seen in the works painted by four hands, such as the two double self-portraits: one shows the two brothers in a carriage during an outing with Xavier’s wife, Julia Chamorel, and a friend; in the other, reproductions of a painting by Manet from the Spanish period and a portrait of a lady by Piero del Pollaiolo that would be a reference for Antonio’s painting can be recognized. In the work of the two brothers, however, distinctive characters stand out. Xavier debuted, in his Parisian years, with militant painting with social themes reflecting his adherence to the Communist Party and dense, mellow brushstrokes reminiscent of the great Spanish tradition, while Antonio adopted a lenticular vision that looked to the Flemish school.

The fourth section is The Modern Painters of Reality 1947-1949: the expression “reality painting” dates back to 1934 and the exhibition Les peintres de la réalité en France au XVIIe siècle curated by Charles Sterling at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris in 1934: another milestone in the process of critical reappraisal of Baroque art, no longer considered a phase of decline after the splendors of the Renaissance. In the short-lived adventure of the Modern Painters of Reality converge the researches of the four signatories of the Manifesto accompanying their first exhibition, which reads, “We recreate the art of the illusion of reality, the eternal and most ancient seed of the figurative arts. We do not lend ourselves to any return, we simply continue to carry out the mission of true painting. [...] Well before we met, each of us had deeply felt the need to search in nature for the common thread that would allow us to find ourselves in the labyrinth of schools that have multiplied in the last half century.” A thought surely also shared by the three artists who joined Sciltian, Annigoni and the Bueno brothers in the five exhibitions held from 1947 to 1949: Giovanni Acci, Carlo Guarienti and Alfredo Serri. From the latter’s meticulous still lifes, to the rigorous study of anatomy with which Acci constructs his figures, to the obvious fifteenth-century references in Guarienti’s painting, their works reaffirm the vocation to the real and the dialogue with the past that characterizes this brief but significant chapter in Italian twentieth-century history. Two trends can be recognized in the works exhibited in this section: the first is related to the war years, with allegories that reflect the tragic scenario of that period and take on a meaning of social commitment. In this sense, Annigoni’s Sermon on the Mountain, also due to its execution that lasted a good fifteen years, represents a synthesis of the poetics of the Modern Painters of Reality. The second trend is, on the other hand, oriented toward a more serene conversation with the visible, toward the joy of a naturalistic vision without implications of denunciation, of which the works of Alfredo Serri and Antonio Bueno are examples.

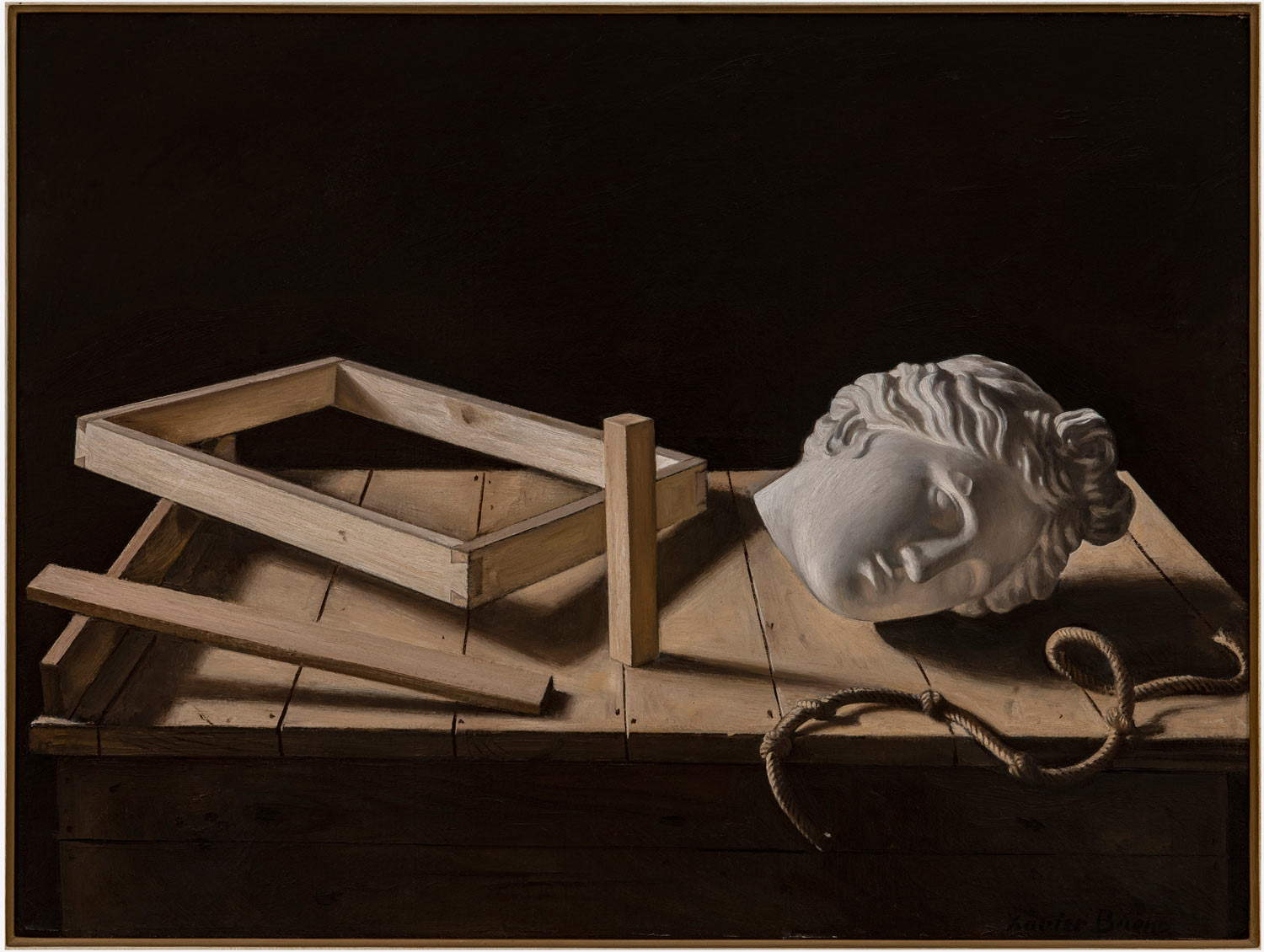

The last section, Metaphysical Atmospheres: the Relationship with Giorgio de Chirico, delves into the relationship of modern reality painters with Giorgio de Chirico, the father of Metaphysics. Sciltian met him upon his arrival in Italy, and a deep lifelong bond was formed between the two. “Gregorio Sciltian is the plasticist par excellence. He is plastic when he paints, plastic when he speaks, he is plastic when he gestures,” de Chirico writes, making us grasp how much the rendering of volumes is the founding element of the Russian artist’s painting. He also has words of sincere appreciation for the Bueno brothers, calling them “two young men full of ingenuity who already possess a great craft and are the antithesis of so many illiterates of painting.” His ascendancy over the two brothers is evident in works such as Metaphysical Composition of 1940, in which Antonio diligently follows the precepts expressed by the pictor optimus in his writing The Return to the Craft, where he recommends that he should take “any plaster casts,” busts or classical statues, to copy them hundreds of times in order to master the true technique that “modernist and secessionist” trends have challenged. All the members of the Modern Painters of Reality group, moreover, approached the enigmatic dechirican theme of the mannequin, stimulated by the commission of Sandro Rubboli, a collector from Milan who had built up a large collection around this subject.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog published by L’Erma di Bretschneider with critical essays by Vittorio Sgarbi, Emanuele Barletti, Emiliana Biondi and Paolo Baldacci, Daniela Ferrari, Stefano Sbarbaro and Luca Scarlini. Opening hours: Tuesday through Sunday 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Friday 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., closed Mondays. Tickets (including visit to the museum and other exhibitions): full 11 euros, reduced 7 euros, free for children under 14 and disabled. For info visit the Mart website.

|

| The Modern Painters of Reality on display at the Mart in Rovereto: Sciltian, Annigoni, the Buenos |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.