From December 6, 2024 to April 21, 2025, Palazzo Roncale in Rovigo will host an exhibition dedicated to the story of a very young woman from Rovigo, Cristina Roccati (Rovigo, 1732 - 1797), known as a symbol of history and collective memory. Cristina Roccati, the woman who “dared” to study physics, the brainchild of Sergio Campagnolo, is promoted by the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Padova e Rovigo, with the support of the Accademia dei Concordi and the Municipality of Rovigo, and the scientific curatorship of Elena Canadelli. “She dared to study,” because at the time, that from a small town, Rovigo, which in the eighteenth century had a population of roughly 5,000 inhabitants and an economy that was certainly not among the most flourishing, a girl of just 15 years old would leave for Bologna to study at the University there, was unheard of. And even more incomprehensible, and perhaps scandalous, seemed to be the subject of her studies: subjects that were beyond the competence proper “of women,” the editor points out.

Even though it was the Age of Enlightenment, universities continued to be exclusive training grounds for wealthy males. In the world, only two women had, at that time, attained degrees: Elena Cornaro Piscopia and Laura Bassi, the former at the University of Padua, the latter at the University of Bologna. And it was to the latter that, in 1747, when she was only 15 years old, Cristina turned. She arrived in Bologna escorted by an aunt and her housemaster to study logic, philosophy, meteorology, geometry and physics, the first “off-campus” student in history. Her father had set his sights on her instead of her brother. The figure of Roccati will make it possible to explore these highly topical issues in historical terms. She has also been named after one of the telescopes that will be launched into orbit as part of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) PLATO project, whose mission is to identify extrasolar planets similar to Earth-a new adventure for a woman who dedicated her life to science and the study of nature in the 18th century.

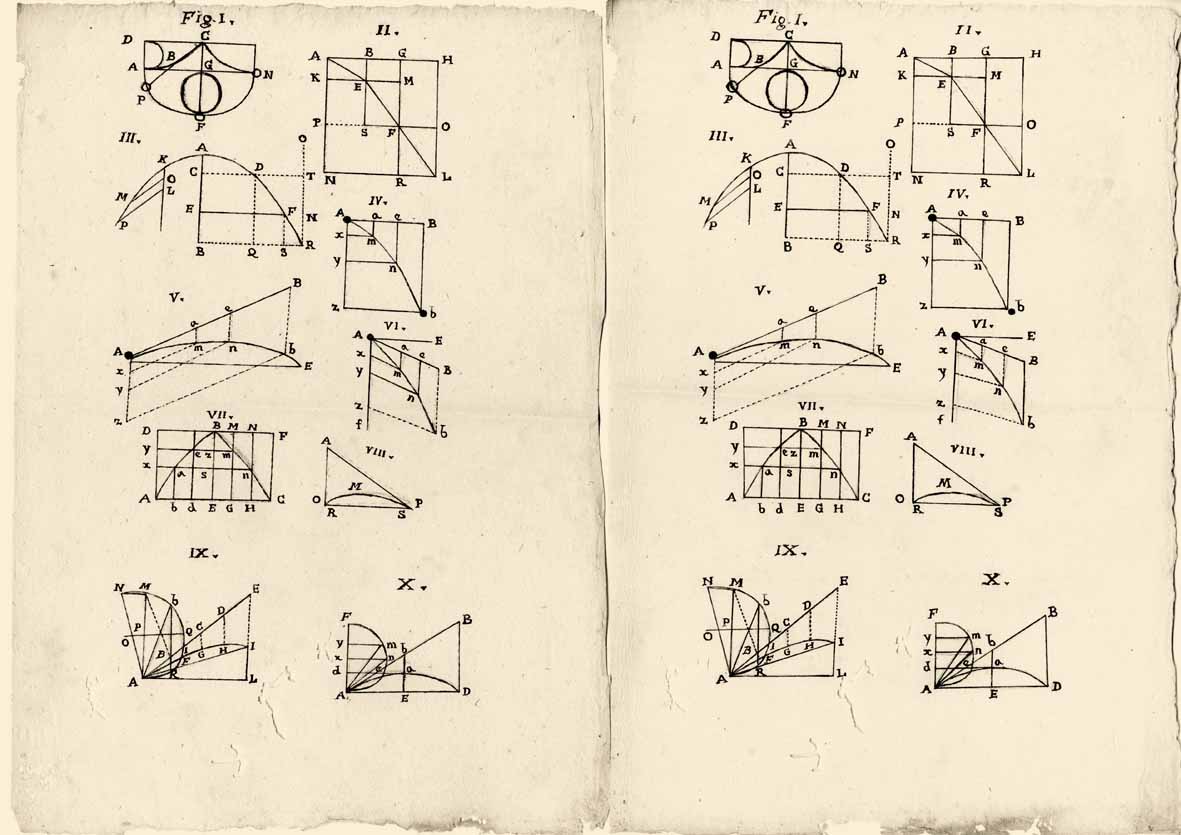

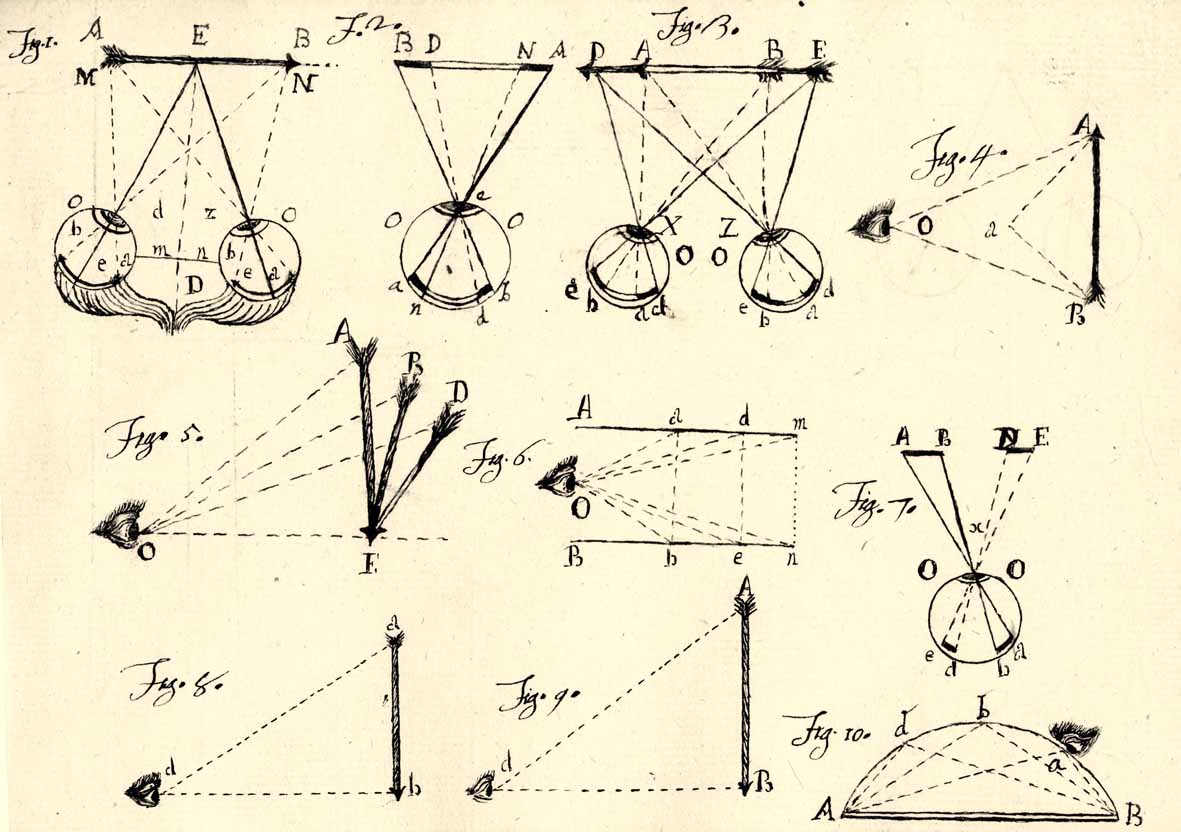

“In a world without women like the world of science at the time,” says the curator, Professor Elena Canadelli, "Roccati graduated in 1751, just 19 years old, and the following year moved to Padua to continue her education with the study of astronomy and Newton’s physics. Her career had actually begun with erudite and occasion poetry, composed for example for the weddings of prominent personalities, an activity that had made her appreciated not only in her hometown but also in Bologna and other academies in Italy.

A friend of the influential Rovigo man of letters Girolamo Silvestri, she was accepted into the Accademia dei Concordi in Rovigo, an important cultural and scientific coterie of the time. Forced to leave Padua as early as 1752, because of the financial scandal in which her father had been involved, the young Roccati devoted herself from that time on to teaching physics in her hometown, addressing herself mainly to the members of the Accademia dei Concordi, who in 1754 appointed her, not without protest and even controversial resignation, their “Prince.” After her lively experiences in Bologna and Padua, Cristina Roccati’s life was always spent in Rovigo, where she brought Galilean science and Newtonian physics, in lectures that have come down to us to this day and that give us a cross-section of the science and society of the time," the editor further anticipates.

"Despite the difficulties, thanks to an ill-defined boundary between public and private, science and the marvelous, in the second half of the 18th century some women managed to carve out a role for themselves in science. Think of figures such as mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi in Milan and physicist Laura Bassi in Bologna, or, in France, mathematician Émilie du Châtelet. Roccati from Rovigo was also among them. The exhibition restores the voice to one of the protagonists of this electrifying season of science, through an exhibition focused on the rediscovery of this forgotten figure. It will also recount some historical and scientific aspects of the 18th century, the century of reason and theEncyclopédie, Voltaire and the French Revolution, but also of the spread of Newton’s theories among the uninitiated and the wonder aroused by natural phenomena such as electricity. During the Roccati years, the fashion for electricity shows and experimental demonstrations won nobles and academics in search of fame and notoriety, enlivening the evenings of courts and drawing rooms, while the first popular science books, such as The Newtonianism for Ladies (1737) by the Venetian-born writer Francesco Algarotti or Lectures on Experimental Physics (1743-48) by the Frenchman Jean Antoine Nollet, multiplied. As with many women of the time, a veil fell over her life and work after her death, a veil that the exhibition at Palazzo Roncale aims to lift in order to trace through her the relationships between science, society and the role of women in the Age of Enlightenment. For a long time women have been excluded from institutional paths in science, and even today the issue of the presence/absence of women in science continues to cause reflection and discussion, with the persistence of gender inequality in scientific subjects."

|

| The girl who dared to study physics: the extraordinary story of Cristina Roccati on display in Rovigo |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.