The elephant of Rome: an exhibition commemorates the 90th anniversary of the discovery of Elephas Antiquus fossils

Ninety years ago, fossil remains of elephant(Elephas antiquus) were discovered in Rome at the base of Velia Hill, near the Colosseum. Today, the fossils, preserved in the Antiquarium of the Capitoline Museums, have been restored, and the intervention has provided an opportunity to propose an exhibition with a set of works that shed light on a sector of the central archaeological area affected in the 1930s by destruction and profound urban transformations. A hundred or so of these works, including archaeological finds, graphic designs and works of art, entirely from the Capitoline collections, some of which were identified during recent research and exhibited to the public for the first time, thus make up the exhibition 1932, the Elephant and the Lost Hill, scheduled from April 8 to May 24, 2022 at the Mercati di Traiano - Museo dei Fori Imperiali. The exhibition, curated by Claudio Parisi Presicce, Nicoletta Bernacchio, Isabella Damiani, Stefania Fogagnolo, Massimiliano Munzi, is promoted by Roma Culture, Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali with the collaboration of Archivio Luce. Organization Zètema Progetto Cultura.

In just two years, between 1931 and 1932, a hill, the Velia, which stretched between the slopes of the Oppio and the foothills of the Palatine, separating the area of the Imperial Forums from the Colosseum, was razed in the heart of Rome. The intervention on the one hand solved the need to connect Piazza Venezia, Via Cavour, and the new districts of the Caelian and Esquiline, and on the other hand allowed for the creation of a monumental and scenic road from Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum. The intent was to create a promenade flanked by the monuments of the ancient city that were being recovered by the demolitions of the Alessandrino Quarter, which had been in progress since 1924. The new city artery, which took the name of Via dell’Impero (today’s Via dei Fori Imperiali), was inaugurated on October 28, 1932 on the occasion of the celebration of the tenth anniversary of the March on Rome, becoming from that moment the privileged place for the parades and rituals of the fascist regime.

The price paid by the artistic and archaeological heritage, however, as a result of this earthworks, was very high. It began with the almost total dismantling of the Villa Rivaldi garden, which stretched across the top of the hill to the shoulders of the Basilica of Maxentius. The archaeological stratification was then undermined, which turned out to be very rich in evidence from the Roman period, particularly the remains of a domus with well-preserved frescoes and numerous statues. But the most surprising discovery was made on May 20, 1932, when numerous remains of fossil fauna came to light, among which the skull and tusk of elephant Elephas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus constitute the most famous find. The news immediately resonated in the press. Antonio Muñoz, director of the 10th Department of Antiquities and Fine Arts of the Governorate of Rome and supervisor of the work, wrote that “here, under the Velia hill was the zoological garden of prehistoric Rome.” Recovery operations took place with great celerity: the Elephas, hastily removed, was then transported to the Antiquarium Comunale del Celio, “where it was forgotten,” as Antonio Cederna would later write.

The exhibition consists of four sections in which, in a journey back in time, some important stages of this story are illustrated: the earthworks with the plans for the architectural arrangement and the way in which the archaeological materials found were collected; the monumental complex of Villa Rivaldi, heavily tampered with by the works; the evidence of a rich domus that remained in use for a long time in the imperial period; and the discovery of the remains of the Elephas antiquus. In this narrative, in addition to the archaeological finds, graphic designs and art objects, period films preserved in the archives of the Istituto Luce and a video with images from the archives of the Capitoline Superintendency are also offered to the public, which are useful to deepen the themes discussed in the exhibition.

In the first section, the Velia earthworks is evoked, highlighting two aspects of that gigantic urban construction site: the discoveries, made in the absence of scientific criteria, of innumerable archaeological finds and the architectural arrangement of the cut of the hill in view of the opening of Via dell’Impero. The first aspect is presented in the exhibition through a selection of archaeological materials unearthed during earthworks, dating from ancient to modern times. Their seemingly random arrangement is meant to give an idea of the manner in which the materials were recovered, collected without distinction of context of discovery, and their storage in crates, which were then accumulated in municipal storage facilities. Referring instead to the second aspect are some drawings and plans for the retaining wall of the Villa Rivaldi garden, drawn up by Antonio Muñoz and his collaborators. Partly unpublished, the drawings show the variety of solutions devised.

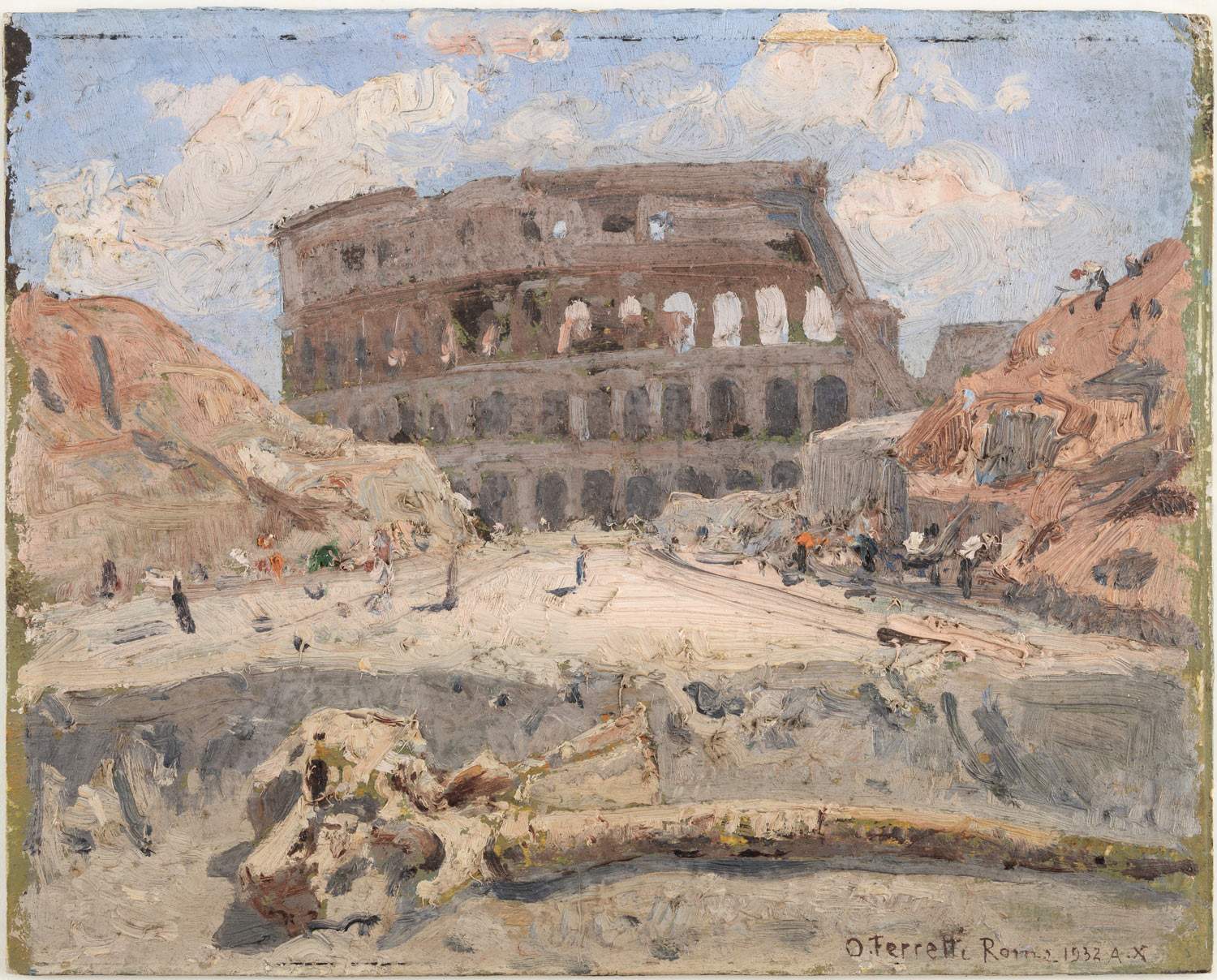

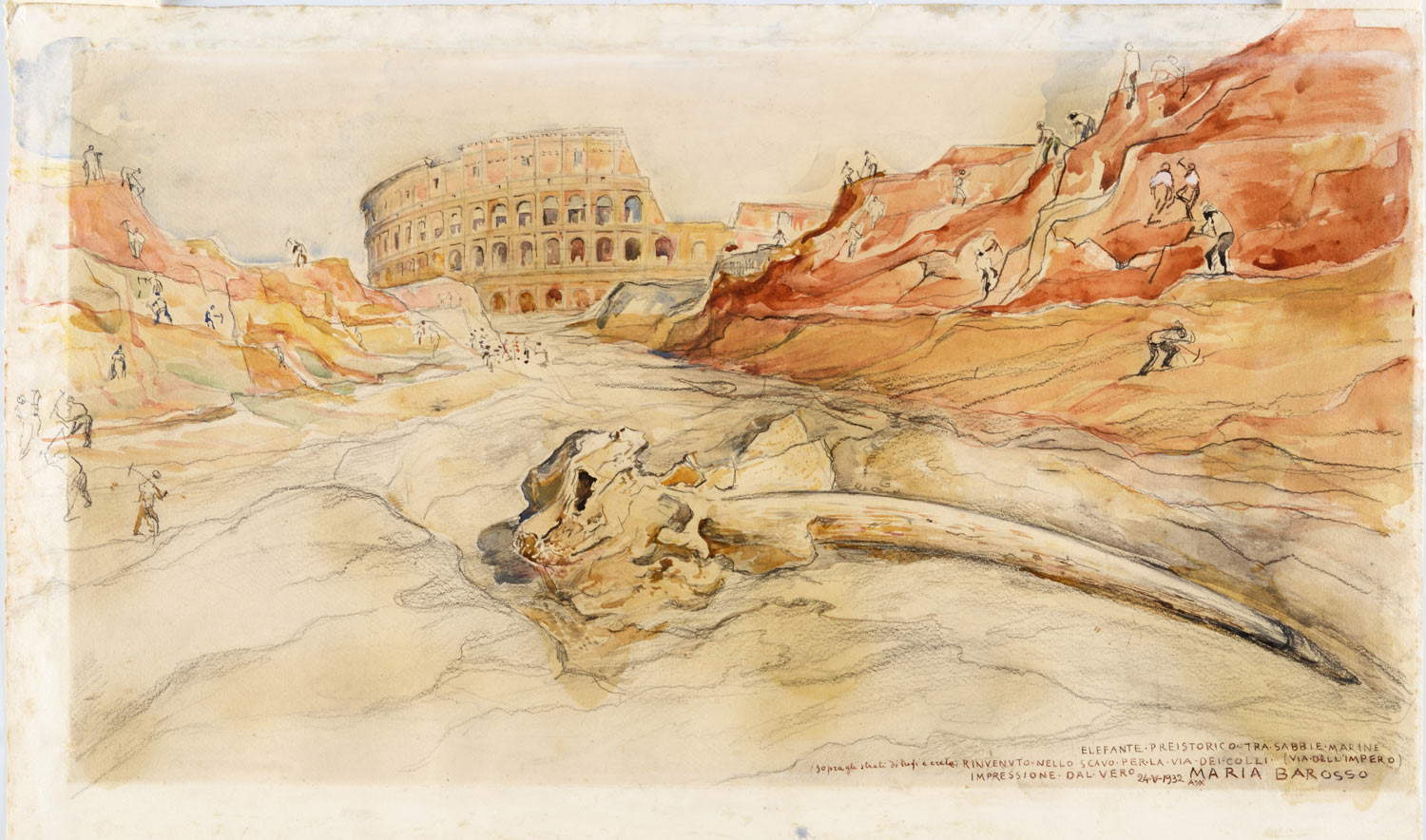

The second section is devoted to the garden of Villa Rivaldi, a splendid residence built on top of the Velia by Monsignor Eurialo Silvestri starting in 1542. Having passed through the hands of several owners, in 1660 the villa was sold by Cardinal Carlo Pio of Savoy to the Conservatorio delle Zitelle Mendicanti, an institution intended for the reception and education of abandoned maidens. On the eve of the Velia’s land clearance, the Governorate of Rome commissioned Maria Barosso and Odoardo Ferretti to paint some views of the villa’s garden, which would soon be destroyed. The initiative was part of a widespread practice at the time: in fact, painting was thought to be more adequate than photography-which was considered a mere mechanical method of reproducing images-to render the fervor of the work in progress or to appropriately document the frequent discoveries of antiquities. The paintings displayed in this room are the fruit of that work.

The third section is reserved for evidence of the pictorial decoration of the cryptoporticus of a large Roman imperial-era domus intercepted by the earthworks, whose imposing structures were completely demolished. The complex consisted of two levels, the lower level of which had a cryptoporticus equipped with a nymphaeum; on the upper level was a porticoed courtyard with a rectangular plan. The decoration consisted of two distinct pictorial phases, one from the late 1st-early 2nd century AD, the other from the late 2nd-early 3rd century AD, reproduced by Ferretti in watercolors, some of which are on display in the exhibition. Four fragments of frescoes, recovered before the demolition of the structures, are presented to the public for the first time. They depict characters and animals, which decorated the panels in which the walls were scanned in the second pictorial phase.

Finally, the fourth section displays the remains of the skull and left defense (tusk) of the ancient elephant Elephas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus, found in the geological layer about 11 meters from the top of the hill. Three watercolors by Barosso and Ferretti’s oil take the viewer through the opening stages of the Velia cut, with the first appearance of the Colosseum, the uncovering of the remains of the elephant skull and defense lying at the route of the Via dell’Impero, and finally, the majestic geological stratification brought to light by the advancing work.

For all information you can visit the Trajan’s Markets website.

|

| The elephant of Rome: an exhibition commemorates the 90th anniversary of the discovery of Elephas Antiquus fossils |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.