The Crema e del Cremasco Civic Museum devotes an entire exhibition to the figure of the vampire

The Museo Civico di Crema e del Cremasco presents from October 19, 2024 to January 12, 2025 the exhibition Vampires. Illustration and Literature between Blood Cult and Return from Death, curated by Lidia Gallanti with Edoardo Fontana and Silvia Scaravaggi. On display are more than two hundred works from twenty Italian public libraries and private collectors, including literary and poetic texts, often illustrated, published in volumes and in magazines, engravings, loose sheets, original editions and iconographic material, through which it is intended to investigate the phenomenon that takes shape around the figure of the vampire, from its genesis in ancient myths and beliefs to the pop icon of contemporaneity.

The term “vampire” appears in European literature around 1730, although the roots of this figure go back much further. It arose in different cultures and religions, united by the need to explain the esoteric phenomena of the return from death, symbolically representing the struggle between good and evil. Over time and changing society, the vampire has transformed into an ambivalent icon, becoming a polyhedron of multifaceted presences that, through the centuries, has acquired an ambiguous, dark and uncertain appeal. The vampire is a fluid being with no definite sexual connotation, straddling life and death, resisting natural laws and subverting them, incarnating in ever-changing bodies and contaminating various genres and forms of art and literature.

From the Mesopotamian myth of Lilītu (Lilith), demon of the night, we move on to Hellenic cults, such as the controversial affair of the Homeric nèkyia, a necromantic rite that awakens the spirits of the dead. The exhibition includes illustrations by John Flaxman and William Russell Flint, Remy de Gourmont’s text illustrated by Henry Chapront, and Edoardo Fontana’s contemporary cycle bearing the title. The exhibition also explores early esoteric and pseudoscientific treatises of the 18th century, such as Michael Ranfft’s seminal De masticatione mortuorum in tumulis, published in Leipzig in 1725 (Biblioteca Manfrediana in Faenza). The Dissertations of the French abbot Augustin Calmet (Queriniana Library in Brescia, Passerini-Landi Library in Piacenza and Bianchessi Collection in Crema) derive from these same origins.

The existence of upiri, vrikolaki and strigoi was refuted by figures such as the Dutch physician Gerard Van Swieten, in his Vampirismus (1787, Manfrediana Library, Passerini-Landi Library), and by Archbishop Giuseppe Davanzati of Trani, author of Dissertation on Vampires (1789, Passerini-Landi Library). A similar skeptical approach is found in the rarely cited Lettera di un Amico ad una Dama sopra i Vampirj, published in Venice in 1765 and exhibited by the Biancardi Collection in Milan.

In the late 18th century, Enlightenment positivism gave way to a more intimate and emotional literature, which introduced early Romanticism and the figure of the belle dame sans merci. In this mysterious and deadly woman one can recognize the premise of themodern idea of the vampire. This is evident in Lilith, depicted in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s famous painting, and in John Keats’ Lamia and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Christabel, also illustrated by Lucien Pissarro (Eragny Press, 1904). The exhibition displays the lithograph of John William Waterhouse’s Preparatory Drawing for Lamia (1905), Gerald Metcalfe’s illustrations, George Frampton’s color and gold lithograph Christabel (1898), and Frank Sepp’s art deco etchings for Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Bride of Corinth (1925, Proverbio Collection, Milan and Lisbon).

In 1816, at Villa Diodati on Lake Constance, Lord George Gordon Byron, his secretary John William Polidori, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin met. The group decided to challenge each other in writing tales of terror. Mary Shelley conceived her masterpiece Frankenstein here, the first Italian edition of which is on display in the exhibition (de Luigi, 1944). From the inspiration of an unfinished short story by Lord Byron, A Fragment (a late 19th-century copy and one of the earliest Italian translations are on display), Polidori wrote The Vampyre (1819), the first modern short story on the subject. Lord Ruthven, inspired by Byron, is a cruel figure acting within upper-class, noble society. In Italy, the tale appeared under the title Il vampiro in the geography and travel journal Il Raccoglitore (1821, Biblioteca di Lovere). In the same years, Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann wrote the dark and terrifying Vampirismus, of which the first Italian translation (Battistelli, 1923, Biblioteca Statale di Cremona) and illustrations by Franz Wacik are on display in the exhibition.

After Charles Baudelaire, the “muse corrupted by the aesthetics of evil” becomes a protagonist in art and literature through the undead and returning female figures of Edgar Allan Poe, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu and Rudyard Kipling. The sublimation of terrible beauty transcends romantic imagery to become the femme fatale. On display are books with illustrations from Poe’s horror tales, such as the images for Ligeia and Berenice done in etching by Wogel, published in 1884 (Bandirali Collection of Crema). Poe also inspired artists such as Harry Clarke, Byam Shaw, Edmund Dulac, and Alberto Martini. Interestingly, the vampire is depicted in continuous decontextualization, as in the lithograph in which Martini portrays Marchesa Casati as a vampire.

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’sCarmilla, first published in The Dark Blue magazine, depicts the contradictions of respectable England and becomes a symbol of an increasingly free sexuality, illustrated in the 1980s by Leonor Fini. Different is the character of Erzsébet Báthory, depicted by Hungarian post-impressionist artist István Csók, whose etching is on display.

The figure of Judas, as a suicide, is often associated with the vampire. Aubrey Beardsley created A Kiss of Judas in 1893 to accompany Julian Osgood Field’s short story of the same name in Pall Mall Magazine. Beardsley is related to Marcus Behmer, with images published in his Salome that include the monstrous butterfly-vampire, a symbol of the medium between the earthly and chthonic worlds. In previous years a French translation of Ludovico Maria Sinistrari’s De Demonialitate had been published, a manuscript rediscovered by a Paris publisher. Sinistrari regarded the vampire as a demon who animated the sleeping with licentious fantasies. Also from those years is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Olalla (1885), the Spanish vampire who between guilt and Victorian respectability was translated by Alfred Jarry in 1958 for Dossiers acénonètes du Collège de Pataphysique.

In 1897 Bram Stoker published Dracula in London, a title inspired by the nickname of Prince Vlad III of Wallachia. On display in Crema are original English and American editions from the early 20th century, along with a rare anastatic of the woodcut booklet with Vlad III’s portrait, maps of Transylvania and naturalistic illustrations of bats, material that inspired Stoker. The first partial Italian translation was published in Milan by Sonzogno in 1922 as Dràcula. The Man of the Night (Biblioteca Manfrediana), while the unabridged edition did not appear until 1945 by Fratelli Bocca (Biblioteca Manfrediana).

The figure of the vampire also lands in Japan, finding its place in the Japanese imagination while at the same time becoming Japanese. On display is the first Japanese edition of Dracula translated by Teiichi Hirai in 1956, the fine Vampire’s Box (2022) by Takato Yamamoto, and other illustrations and publications.

In the Italian area, some texts written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries include Vampiro. A True Story by Franco Mistrali (1869, Biblioteca Minguzzi-Gentili, Bologna), novellas by Francesco Ernesto Morando, Luigi Capuana, Giuseppe Tonsi (Il vampiro, 1904, Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai, Bergamo), Daniele Oberto Marrama, and the poem Il vampiro by Amalia Guglielminetti.

Czech artists from the Symbolist area gathered around the magazine Moderni Revue, whose most iconic cover, created by Karel Hlaváček in 1896, depicted precisely a vampire woman. Hlaváček also wrote Upír, a melancholy poem published in the collection Late to Dawn, which inspired František Kobliha to create one of his extraordinary cycles of woodcuts. The Romanian strigoi is the restless spirit of a deceased person who comes out of the grave at night to bring harm to the living. A vampire woman is the protagonist of Mircea Eliade’s novel Signorina Christina, displayed in the first, rare Romanian edition, as well as in the early Italian and French editions. Within the novel, Eliade quotes Mihai Eminescu, who is present in the exhibition with the first Italian translation of the poem Calin and the magazine Convorbiri Literare, where the poem Strigoi appeared.

From Stoker’s Gothic novel derived both Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s film Nosferatu (1922) and its remake directed by Werner Herzog and starring Klaus Kinski and the young Isabelle Adjani. On display is a copy of the poster in the 1979 Belgian edition, designed by David Palladini. Murnau’s silent film owes much of its cultural impact to the genius of producer, set designer and graphic designer Albin Grau, who designed numerous versions of Count Orlok, drawing inspiration from the work of Alfred Kubin and especially Hugo Steiner-Prag, illustrator of Gustav Meyrink’s Golem. The exhibition compares the two artists.

Neil Jordan’sInterview with the Vampire (1994) is based on Anne Rice’s book of the same name published in 1976, the progenitor of a successful series of vampire stories. In 1975 Stephen King published ’Salem’s Lot, expounded along with Richard Matheson’s I am Legend, which first attributed vampirism to a virus.

Beginning with the anthology edited by Elinore Blaisdell in 1947 and illustrated by the artist herself, numerous literary studies and collections were published between the 1950s and 1970s. Vampires Among Us by Ornella Volta and Valerio Riva is one of the first comprehensive international collections on the subject. Volta also offered an eccentric view of vampire imagery with Le vampire, published in French and later translated into Italian. Io credo nei vampiri by Milanese journalist Emilio de’ Rossignoli also stands out on the theme.

Also on display are works by the most representative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Henry Chapront for M.me Chantelouve, the exhibition’s guiding image, Félicien Rops, Marcel-Lenoir, Alméry Lobel-Riche, Valère Bernard and Carl Schmidt-Helmbrechts. Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona’s Drypoint Pictures of the Evening (1932) testifies to the evocative power of literature and art. Two lithographs by Frenchman Georges De Feure, Les vices entrent dans la ville (1894) and L’amour aveugle, l’amour sanglant (1893-1894), evoke evil.

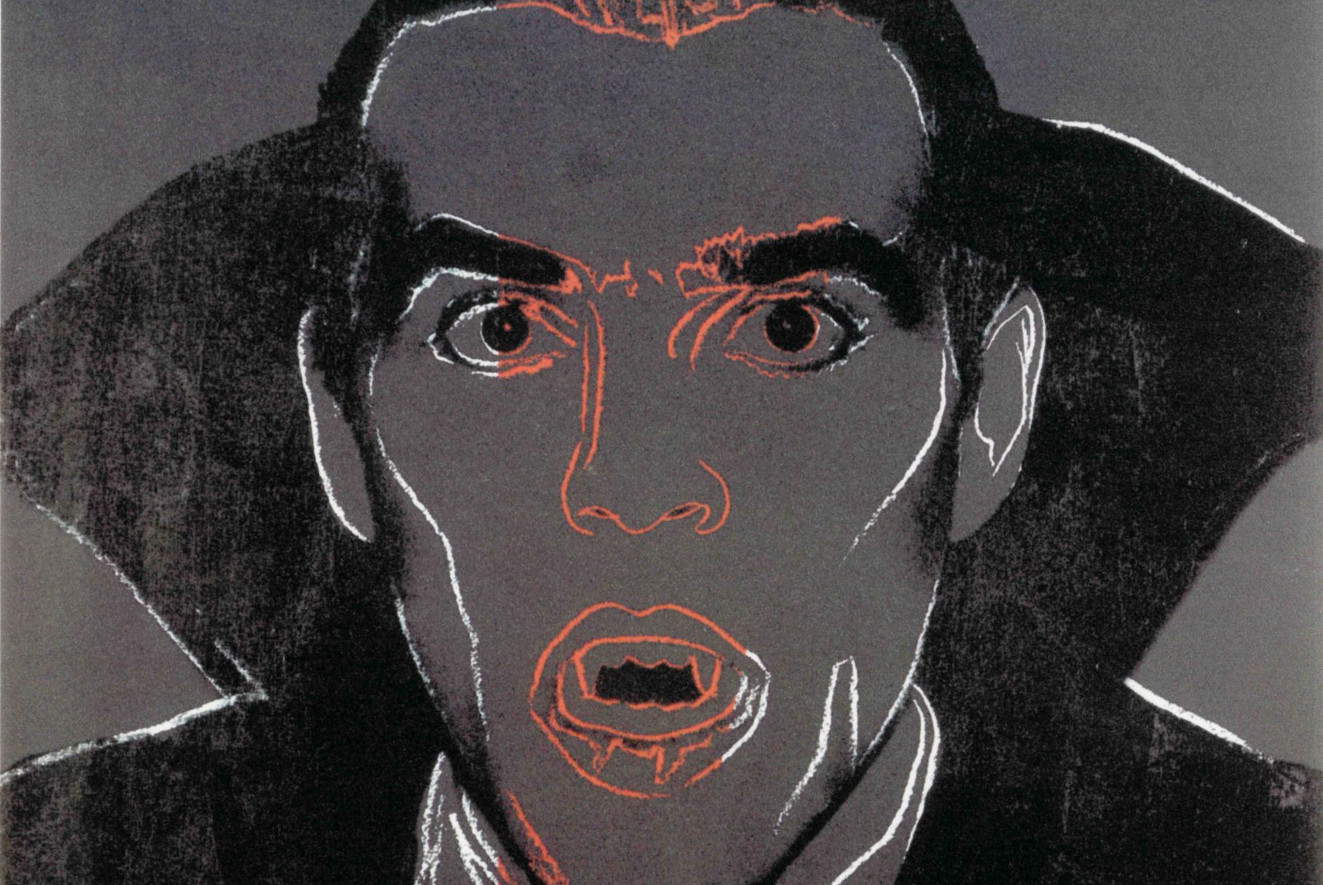

Edvard Munch devoted several etchings to vampires, depicted in feral gestures strained between love and pain, such as a 1906 vignette. The tormented lines of Austrian expressionist Oskar Kokoschka (Fiori Collection in Bologna), Max Ernst’s surrealist illustrations for collages in Une semaine de Bonté, and Andy Warhol’s pop synthesis, which includes Dracula among the ten icons of human history, are all represented in the exhibition with color lithographs from the Myths Suite series (1981). The 1968 lithograph by Roland Topor, also author of the novella The Vampire’s Teeth, departs from the common imagination by leading us into a dreamlike dimension between irony and fright.

Vampires also conquer the covers of Alan Ford and Dylan Dog comics, creeping into the pages of Corto Maltese and Guido Crepax’s Dracula. The narrative becomes more ambiguous in the works of contemporary artists such as Agostino Arrivabene and Edoardo Fontana. Female figures are the protagonists of Andrea Lelario’s etching Sister Brides and Sonia De Franceschi’s intaglios. Evoking the atmospheres of Nosferatu are David Fragale’s India ink and Stefano Grasselli’s woodcuts, as well as Jacopo Pannocchia’s rarefied architectures. Agnese Cascioli’s photographs, Simona Bramati’s watercolor Carmilla, Irene Di Oriente’s esoteric sign, and Marco Furlotti’s original Carfax panel for Dracula narrated and illustrated draw new bridges between past and future.

Produced in collaboration with Aretè Associazione Culturale and Alla fine dei conti di Mantova, the exhibition is accompanied by a catalog published by the Museo Civico di Crema with a preface by Antonio Castronuovo and texts by Elena Alfonsi, Paolo Battistel, Carla Caccia, Marius-Mircea Crișan, Mario Finazzi, Edoardo Fontana, Lidia Gallanti, Roberto Lunelio, Silvia Scaravaggi, and Elena Vismara.

The exhibition can be visited on Tuesdays from 2:30 to 5:30 p.m.; Wednesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to noon and 2:30 to 5:30 p.m.; Saturdays, Sundays and holidays from 10 a.m. to noon and 3:30 to 6:30 p.m. Closed on Mondays.

|

| The Crema e del Cremasco Civic Museum devotes an entire exhibition to the figure of the vampire |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.