From Aug. 5 to Oct. 30, 2022, Vôtre Spazi Contemporanei in Carrara is organizing two exhibitions (opening Aug. 5 at 9 p.m.) at the Palazzo del Medico in Piazza Alberica: the group show Summer Lights, curated by Nicola Ricci and Federico Giannini, and the solo show of sculptor Novello Finotti. Summer Lights brings together the works of twenty-four artists and is part of a strand of exhibitions on trends in Italian painting and sculpture from the 1950s to the present that Vôtre has been organizing for a number of years (the most recent being the exhibition Uguali Disuguali held between November and January).

Summer Lights, taking its cue from the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Group of Eight, which proposed a third way between abstraction and reality while the debate pitting the positions of abstractionists and figurative artists against each other flared up, traces some of the major events that have affectedItalian art since 1952, exhibiting works by two members of the Ottos, namely Antonio Corpora (Tunis, 1909 - Rome, 2004) and Ennio Morlotti (Lecco, 1910 - Milan, 1992) to arrive at the early 2000s through the presence of paintings and sculptures presenting research on light and color. From the geometric abstractionism of Piero Dorazio (Rome, 1927 - Perugia, 2005) to the spatialism of Turi Simeti (Alcamo, 1929 - Milan, 2021) and Dadamaino (Edoarda Emilia Maino; Milan, 1930 - 2004), from the objective painting of Mario Schifano (Homs, 1934 - Rome, 1998) to the neo-surrealism of Aldo Mondino (Turin, 1938 - 2005), from the Transavanguardia of Sandro Chia (Alessandro Coticchia; Florence, 1946) to the Nuovi-Nuovi as Salvo (Salvatore Mangione; Leonforte, 1947 - Turin, 2015) and Luigi Ontani ( Vergato, 1943), to arrive, passing through the Nuova Scuola Romana of Piero Pizzi Cannella (Rocca di Papa, 1955), the citationism of Athos Ongaro (San Donà di Piave, 1947), the recovery of tradition by Wainer Vaccari (Modena, 1949) and theirony of Maurizio Cannavacciuolo (Naples, 1954), to the more recent trends embodied by artists such as Antonia Ciampi (Bologna, 1959), Marco Cingolani (Como, 1961), Angelo Filomeno (Ostuni, 1963), Federico Fusj (Siena, 1967) and Santiago Ydáñez (Jaén, 1967). There is also no shortage of a section devoted to artists active in the Carrara area but who have exhibited in international contexts, such as Luciano Massari, Silvia Papucci, Roberto Rocchi, Silvio Santini, and Enzo Tinarelli.

"With Summer Lights the public has the opportunity to visit a sort of anthology of five decades of Italian painting and sculpture,“ say curators Ricci and Giannini. ”The path follows some lines that start exactly seventy years ago and come, through filiations, reactions and reworkings, up to the present day. After Equals and Unequals, which focused mostly on harmonies and dissonances between often opposing languages, Summer Lights has a more classical slant, with the aim of tracing a small and necessarily incomplete history of painting and sculpture to observe how the languages elaborated by historicized artists have been received by those of subsequent generations."

The solo show of Novello Finotti (Verona, 1939), on the other hand, brings together several important sculptures by the Veneto artist, known for his works situated somewhere between reality and fantasy, an artist who works with marble and bronze and has exhibited all over the world. Born in Verona in 1939, Finotti lives and works between Sommacampagna and Pietrasanta. After studying at the Cignaroli Academy, he made his 19-year-old debut in 1958, exhibiting his works in Assisi, then taking part in the III International Bronze Competition. In 1964 he exhibited in New York and two years later made his debut at the Venice Biennale, where he returned in 1984 with a solo room. Finotti also counts two appearances at the Rome Quadriennale (1976 and 1986). His major solo exhibitions include those held at Galleria Jolas in Milan (1972), the Italian Embassy in Tel Aviv, Israel (1976), Jolas Jackson Gallery, New York (1977), Galerie Berg Home, St. Gallen, Switzerland (1977) theItalian Cultural Institute, San Francisco (1980), Palazzo Te, Mantua (1986), Galleria Marilena, Liakopoulus, Athens (1980), Galleria Forni, Bologna (1991 and 2005), Galleria Credito Valtellinese, Refettorio delle Stelline, Milan (1995), Nardin Gallery, New York (1998), Castello Scaligero, Malcesine (2000), and Abbazia di Rosazzo in Manzano.

The two exhibitions can be visited at the halls of Vôtre Spazi Contemporanei (Palazzo del Medico, Piazza Alberica 5, Carrara) Tuesdays through Saturdays from 5 to 8 p.m., from Aug. 5 to Oct. 30. Opening open to all on Friday, Aug. 5 at 9 p.m. The exhibition is free admission. For information call +39 3384417145, email associazionevotre@gmail.com or visit https://www.votrespazicontemporanei.it. Below is the introductory text to the exhibition, by Federico Giannini.

The year 1952 figures among the fundamental years for Italian art in the second half of the 20th century: at the Venice Biennale that year, Lionello Venturi presented for the first time to the public and critics the group of “Otto Pittori Italiani,” which he sponsored, and which was born out of a precise desire that Antonio Corpora had expressed to Venturi himself: the desire to re-found Italian painting by opening a third way between abstraction and figuration, overcoming the rigid divisions that had bridled the artistic debate of the time (the “eight,” namely Afro Basaldella, Renato Birolli, Antonio Corpora, Mattia Moreni, Ennio Morlotti, Giuseppe Santomaso, Giulio Turcato and Emilio Vedova, did not want to be defined as either realists nor abstractionists), and by employing, Venturi would write, "that pictorial language which depends on the tradition that began around 1910 and included the experience of the Cubists, Expressionists and Abstractionists."

The language of the group, which rejected any extremism and aspired to the freedom of being able to express itself with forms that were able to transfigure reality without, however, rejecting or denying it, was destined to be successful from that first exhibition occasion: it will suffice to recall how, just after the 1952 Biennale, Palma Bucarelli, then director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, decided to enrich the museum’s collections by purchasing aAlba by Corpora for 72.170 lire (a little more than a thousand euros today), also chosen for its formal characteristics, being a work in which “the color-light expands beyond the structural layout, penetrating like a ray of sunlight into the surface grid, with an internal and spontaneous dialectic that already places Corpora apart in the post-Cubist abstracting context of the postwar period.” It is from these suggestions, on the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Group of Eight, that the exhibition Summer Lights, in accordance with Vôtre’s recent exhibitions aimed at retracing the events of the last decades of Italian art, and in particular of painting and sculpture, is placed along the series of anthological reviews on therecent Italian art at the Carraresi gallery, with the aim of tracing the threads of part of Italian painting culture between the 1950s and the early 2000s, specifically with a series of paintings presenting research on light and color.

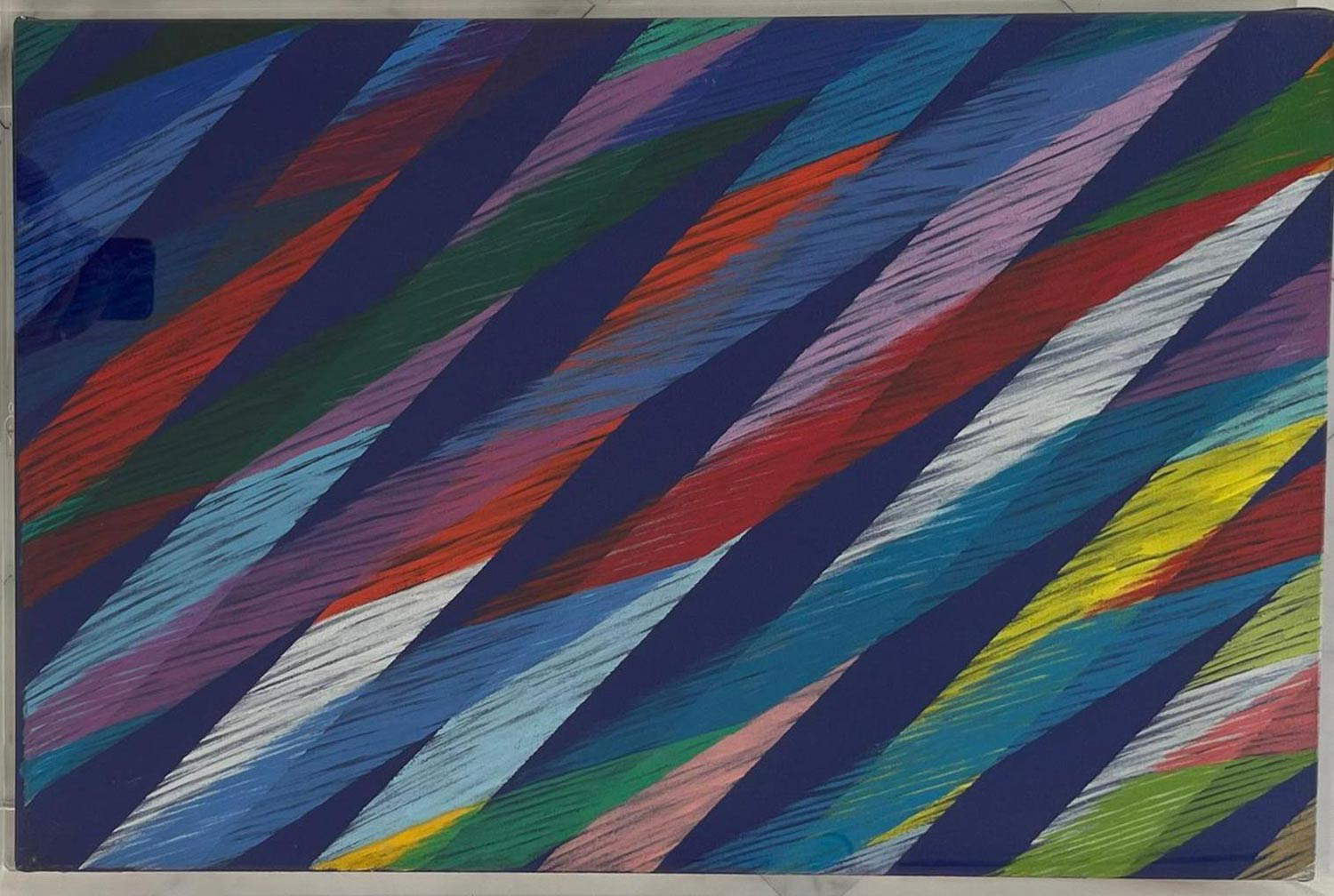

The Otto’s experience would be very short-lived: the exit of two leading exponents, Morlotti and Vedova, would decree the end of the group as early as 1954. Morlotti, in particular, had abandoned the Ottos to approach the “last naturalists” reunited under the aegis of Francesco Arcangeli, animated by the intention of bringing back to the center of artistic action nature, understood in its purest pure physical essence of an element “that is looked at, breathed, felt, and suffered even before it is put into words,” as Arcangeli himself wrote in the essay Gli ultimi naturalisti published that year in Paragone. In parallel, on the opposite side, abstract painting continued to produce its experiments: Having ended the experience of Forma 1, which recognized in formalism “the only means of escaping decadent, psychological, expressionistic influences,” Piero Dorazio, who very young, at only 20’age, was among the signatories of the manifesto in which it was established that “form is means and end,” remained on his positions even after the dissolution of the group in 1951 and continued on the path of geometric abstractionism: the painting, for Dorazio, had to represent nothing but himself, and the Roman-born artist would always remain consistent with this poetic intent, while varying his research on compositions, on colors, which in the 1960s tended to form lattice structures to suggest the presence of a space, and later would dialogue with each other to achieve increasingly pronounced contrasts of light and shadow. In the same years, the researches of the Spatialists led by Lucio Fontana were gaining ground in Italy and, sustained by an innovative and radical poetics and a lucid theoretical framework, they subverted world art by considering the work as “a sum of physical elements, color, sound, movement, time, space, conceiving a physical-psychic unity, color the element of space, sound the element of time, and movement unfolding in time and space” (thus in the 1951 Technical Manifesto of Spatialism ): the fundamental dimensions of existence merge together in the works of the spatial artists, represented in Summer Lights by Turi Simeti, author of a “three-dimensional painting” capable of disrupting the common perception of the painting and oftrigger unprecedented and original relationships between color and light modulated directly by the forms that Simeti conferred on his works, and by Dadamaino (Edoarda Emilia Maino), who made his debut in Milan at the end of the 1950s by presenting himself with his Volumi (Volumes ) which, heirs of Fontana’s Concetti spaziali (Spatial Concepts ), looked at the canvas as an object, a monochromatic form to be explored in the depths of its physical dimension.

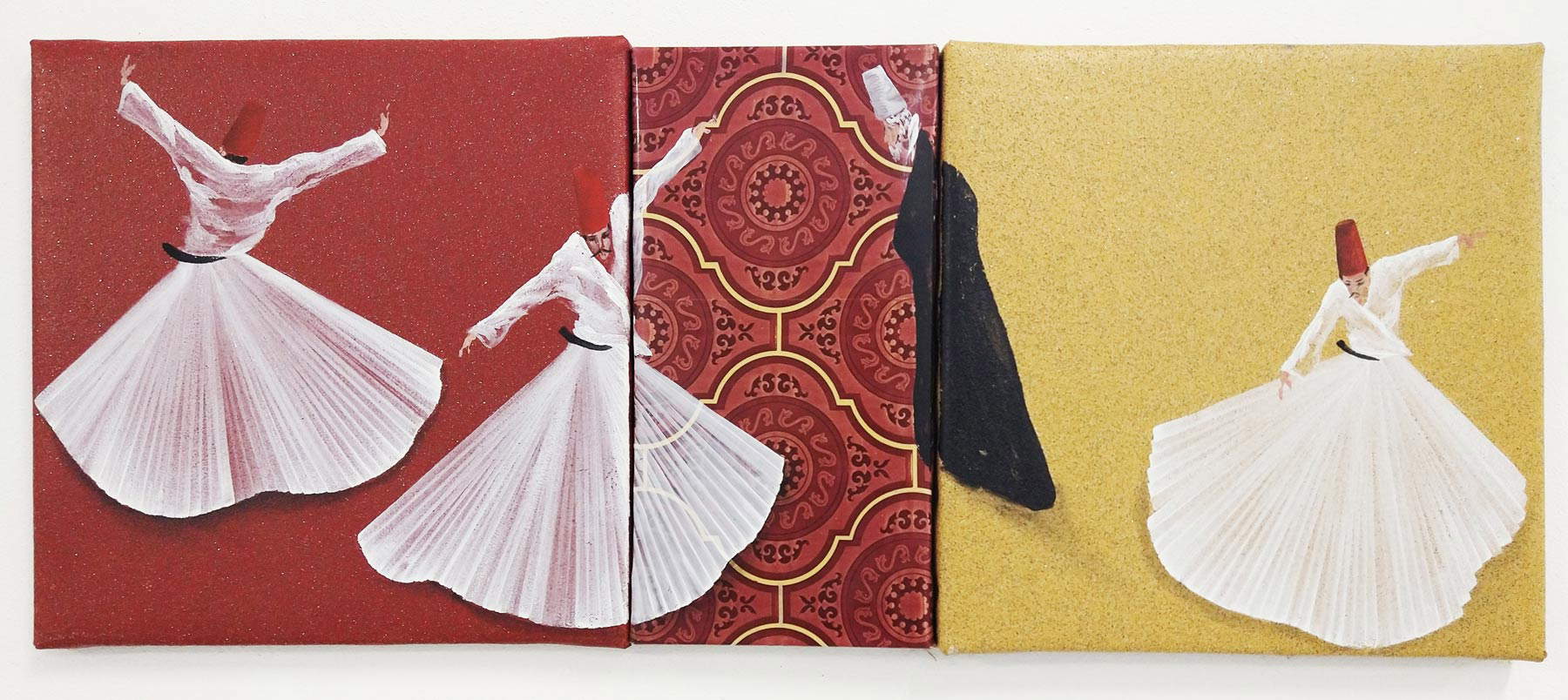

In the 1960s, the response to abstract and informal poetics would take three different paths, the most successful of which was, to use the words of Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, “art that turns to the object, to the symbol, to reality: a ’new objectivity’ as attentive as ever to the imprints of the city and human space.” In this new objectivity, which manifested several points of tangency with the Pop Art that came to the attention of the entire world starting with the 1964 Venice Biennial, was the figure of Mario Schifano, an artist of mediation between painting and photography, that is, a painter who “assimilates from the photomechanical image not already the minute and veristic rendering of detail, but, on the contrary, instantaneousness and poignancy.” Next to the objective painting represented by Schifano, Fagiolo dell’Arco placed programmed art and neo-surrealist art: the latter found one of its most original exponents in the figure of Aldo Mondino, a versatile artist who, during his career, experienced even radical changes in poetics (as when, towards the end of the 1980s, he approached Oriental cultures and began to produce the famous carpets and dervishes).

The so-called return to painting that shook the 1980s after a decade dominated byArte Povera, Conceptual Art, Minimalism, Neo-Dada, Land Art, and Body Art, trends that had relegated to the margins of theinterests of public and critics the researches of those who worked with canvases and brushes, produced in Italy, too, new ferments, which resulted in the affirmation of reactionary phenomena such as Achille Bonito Oliva’s Transavanguardia, which, in 1979, chose a group of’emerging artists, namely Sandro Chia (featured in the exhibition with a Thinking Couple and a Sleeping Man), Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Mimmo Paladino, Nicola De Maria, Marco Bagnoli and Remo Salvadori to propose to the public an art capable of “return to its internal motives, to the constitutive reasons for its work, to its place par excellence which is the labyrinth, understood as ’work within,’ as a continuous excavation within the substance of painting” (thus Bonito Oliva introduced, in 1979, the article La Transavanguardia italiana with which he presented the group). The movement, while presenting itself without a common formal poetics, shared some basic elements, such as subjectivism, eclecticism, the crossing of the avant-garde (hence the name) by means of an art based on manuality, surprise, the artist’s intimate drive and consequently the lack of a basic ideology. Central, in Sandro Chia’s work, is the human figure, read through a neo-expressionist language founded on the use of lines and colors characterized by great boldness, impetuous, of strong impact on the observer. A year later, in 1980, another critic, Renato Barilli, founded the Nuovi-Nuovi group which, moving away as much from the avant-garde as from the radicalism of the Transavanguardia, opted for a postmodern mediation between past and present, between recovery of art history through a marked citationism and elaboration of images obtained with the photographic medium: “From explosion to implosion,” Barilli would write in the catalog of the exhibition Ten Years Later that sanctioned the birth of the group, “from the projection toward the future to the recovery of the past, from the escape outside the sacred precincts of art to a plunge into the heart of the most protected and recognized museum system.” Representing the New-New, Summer Lights features works by Salvo and Luigi Ontani: if the former had made a name for himself with works that openly cited the great art of the past and then landed on a landscape painting characterized by vivid colors and extreme graphic simplicity, the latter moves from tableaux vivants and then navigates continuously between painting, sculpture, mosaic and photography, elaborating a playful and irreverent poetics that draws from the ancient and the modern, fully expressing the postmodern propensity for appropriation and reworking. In the same climate of “return to the past” move, albeit with extremely different results, the figures of Wainer Vaccari, Athos Ongaro and Maurizio Cannavacciuolo: Vaccari looks to the art of the past (particularly Renaissance painting, Symbolism and Neue Sachlichkeit) to produce a distant, disturbing and timeless painting, Ongaro presents himself from the very beginning with an art devoted to the most insolent eclecticism, while Cannavacciuolo presents himself with his elaborate works that conceal different narrative levels under complex and intricate plots, even on a formal level. Alongside the Transavanguardia, the Nuovi-Nuovi and the artists who did not identify themselves with any movement but whose figures stood out for the originality of their language, in the 1980s there emerged a further group, that of the Nuova Scuola Romana, led by Bruno Ceccobelli, Gianni Dessì, Giuseppe Gallo, Nunzio, Piero Pizzi Cannella (the latter present in the exhibition) and Marco Tirelli, one of the last important movements in Italian art: officially born in 1984 with the Ateliers exhibition held at the Pastificio Cerere in Rome, the New Roman School (also known as the “San Lorenzo School”) drew on the Roman School of the 1920s, that of Scipione, Mario Mafai and Antonietta Raphaël, with the idea of going beyond conceptual art and Arte Povera to propose a return not only to manual skills and traditional arts, but to the very sensibility of theartist, and making herself the bearer, Patrizia Ferri has written, of a “glocal” meaning where “a centrifugal and a centripetal tendency, of attention to memory and expansion toward a more global and shared dimension of the artistic experience, in the light of a sobriety inherited from analytical research as opposed to wild internationalism and more successful, both in terms of market figures and on the level of aesthetic values.”

Summer Lights goes on to examine the ways in which various artists born in the 1960s or shortly thereafter have elaborated the different languages of Italian art. Among the artists who look to the past are Angelo Filomeno, who employs the technique of embroidery with references to themes and subjects of antiquity (the public in the exhibition will find one of his large silk vanitas ), Santiago Ydáñez, a Spaniard but long active in Italy who has distinguished for his expressive portraits of monumental dimensions, and Marco Cingolani, who has found his own singular and extremely original way between neo-expressionism and abstractionism, basing his grammar on the almost virtuosic use of color. On the other hand, artists such as Federico Fusj, animated by a continuous tension to merge even distant modes of expression with the aim of exploring the potential of matter, and Antonia Ciampi, whose research is driven by the desire to find points of contact between the human being and the cosmos, are placed on the side of abstraction.

A tribute to artists from Carrara, or active in the Carrara territory, closes the exhibition to trigger a dialogue between the works of some important exponents of the local artistic culture (but who have exhibited in international contexts) and those of the historical path of Summer Lights. Space, therefore, is given to Luciano Massari’s Silent Lands that measure themselves against a Dadamaino Volume , Silvia Papucci’s colorful explosions, Roberto Rocchi’s experiments with marble and LEDs, Silvio Santini’s clean and sinuous forms, and Enzo Tinarelli’s contemporary mosaic to show how the Carrarese panorama continues to maintain a lively and constant momentum.

|

| Sixty years of Italian art on display in Carrara, from Morlotti to Transavanguardia to today |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.