At the two venues of the Nivola Museum in Orani and the Giovanni Marongiu Civic Museum in Cabras, the exhibition On the Shoulders of Giants will be on view from November 30, 2024 to March 23, 2025. The Modern Prehistory of Costantino Nivola, curated by Giuliana Altea, Antonella Camarda, Luca Cheri, Anna Depalmas, and Carl Stein. The exhibition compares the works of Costantino Nivola (Orani 1911 - Long Island 1988) with the evidence of Sardinian Prehistory that influenced him, presented through original artifacts, photographs, and multimedia installations curated by the Visual Computing Group of CRS4. The result of a scientific collaboration between Giuliana Altea and Antonella Camarda, art historians, Luca Cheri and Anna Depalmas, prehistoric archaeologists, and Carl Stein, architect and former collaborator of Nivola, the exhibition is an opportunity to explore the link between Nivola and Sardinia, thanks in part to a group of key works by the artist from private American and Italian collections. This is the first exhibition dedicated to the relationship between the art of Costantino Nivola and the Prehistory of Sardinia, which is developed through an itinerary in which key works by Nivola are placed in dialogue with masterpieces ofEneolithic and Nuragic sculpture andarchitecture.

The title of the exhibition alludes, in addition to the monumental statues found at Mont’e Prama, to the medieval aphorism that compared to the ancients, we are like dwarfs on the shoulders of giants. And Costantino Nivola’s sculpture is inspired from the very beginning by the anonymous masters of Sardinian prehistory. Trained as a graphic and exhibit designer in Monza and Milan, Nivola - since 1939 an anti-fascist exile in the United States - confronted sculpture in 1950. In an international cultural climate that, after the destruction of the war, looked to prehistory as a source of possible renewal of civilization, Nivola rediscovered Sardinia and its extraordinary archaeological heritage, making it the basis of his own art. After World War II, in the wake of the opening to the public of the Lascaux caves in France (1948), the lure of the distant past exerted an attraction on artists all over the world. In the aftermath of the war, Prehistory becomes a mirror of contemporary man’s anxieties, but at the same time it evokes a positive idea of spirituality and community ties in contrast to modern materialism, individualism and dehumanized science. For Nivola, who felt a deep connection with the “primordial” dimension of Sardinia, this positive interpretation of prehistory prevailed above all.

Nivola returned to Sardinia for the first time in 1947. Back in New York, in contact with Jackson Pollock and the artists of the New York School, at that time equally fascinated by totemism and the beginnings of humanity, and following his seminal meeting with Le Corbusier, the artist discovered sculpture. 1950 saw the birth of his first sandcasts, that is, plaster or concrete sculptures made with sand matrices, which blend elements of Surrealism (looking especially to Ernst and Giacometti) with elements of Sardinian folklore, but in particular with the memory of female statuettes from the Neolithic/Eneolithic period such as the so-called Venus of Senorbì and the Mother Goddess of Porto Ferro. After 1952, following another six-month stay in Sardinia as a correspondent for the American Fortune magazine, his interest in Prehistory reached its peak. Thunderstruck by the Nuragic civilization, he travels the length and breadth of the island taking hundreds of photos, visits the excavations of the nuraghe at Barumini, and comes into contact with its discoverer, archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu.

From this moment on, Nivola would feel himself to be the spiritual heir of the ancient lineage of nuraghe builders and bronze sculptors, delivering to the press and critics an image of himself strongly linked to the reminder of Sardinia’s ancestral past. In 1953, his major relief for the Olivetti Showroom in New York transformed the luxurious store on Fifth Avenue into a kind of cave populated by mythical figures, full of pointed references to the pre-Nuragic and Nuragic civilizations of Sardinia. In the years that followed and until the end of his life, Prehistory would remain a constant reference as well as a perennial stimulus for his research: from the references to Nuragic architecture present in his monumental projects, through the development of an original fresco graffiti technique, to the solemn and evocative Mothers made since the 1970s.

“The path,” explains Giuliana Altea, “follows the development of Prehistory in Sardinia, from the appearance of humans to the apogee of the Nuragic civilization. Each moment of the island’s remote past is flanked by fundamental works by Costantino Nivola, in an ideal dialogue that surprises with the punctuality of the references and fascinates with the beauty of the works on display.”

From the first section, in which Nivola recounts his personal myth of origin through a series of works, including an unpublished bronze triptych from the 1960s, that refer to Gaea and Uranus, the divine primeval couple, we move on to the age of the earliest graffiti, which can still be admired in the domus de janas. “These graffiti,” says Antonella Camarda, “constitute a continuous source of inspiration for Nivola: not only does the artist scatter his sculptures with engraved motifs reminiscent of petroglyphs, but, since the mid-1950s, graffiti on fresh plaster becomes one of his favorite techniques for large public decorations, such as the church of Sa Itria in Orani or the playground of the Wise Towers in Manhattan (1964).”

A comparison of some ceramics from the 5th-4th millennia B.C. with the plates Nivola made with ceramist Luigi Nioi in 1980 shows the continuing fascination with these early signs.

“In Sardinia,” Anna Depalmas continues, “the presence of menhirs, large ogival-shaped monoliths from the pre-Nuragic period, to which the second section of the exhibition is dedicated, is particularly widespread. These enigmatic artifacts must have deeply affected Nivola, who mentions them in the early sandcasts of the 1950s, and even more directly in his 1967 Piazza Satta project in Nuoro.”

The centerpiece of the exhibition at the Nivola Museum is the Great Mother, the protagonist of Neolithic/Eneolithic statuary and a central theme in Nivola’s imagination. From the Totems of the 1950s to the Mothers of late maturity, the artist’s female figures retain the ambivalent appeal of their prehistoric ancestors. The exhibition continues with the never-before-proposed parallel between sacred wells, Nuragic monuments linked to the cult of water, and Nivola’s art, which takes up some of their structural and detailed elements in a timely manner. “The theme of water,” explains Carl Stein, “has always been dear to Nivola: fountains play an important role in the decoration of the Morse and Stiles colleges at Yale University, designed by Eero Saarinen (1960-1962, one of the most ambitious projects), and in that of the Wise Towers in New York (1964). Nivola liked to contrast the abundance and waste of water in the United States with the scarcity of water in Sardinia, which makes it precious and feeds the desire for it.”

The section devoted to the Builder, an almost mythical figure with whom Nivola identified, both as a mason’s son and as heir to the distant makers of the nuraghi, closes the exhibition at the Nivola Museum and begins the one at the Giovanni Marongiu Museum in Cabras. “Nivola,” Luca Cheri points out, “sees in the idea of construction the very essence of art. From his fascination with nuragic walls, the Building Blocks series was born in the early 1950s, and the nuragic wall also refers back to numerous sculptures and monuments conceived as spaces to be inhabited, a constant sign of the co-presence, in Nivola - of the memory of nuragic architecture and the modernist need for an art for the community.”

At the Cabras museum, which already houses the Giants of Mont’e Prama, the exhibition continues with a comparison of Nuragic stone and bronze sculptures with those of Nivola. Nuragic bronzes constitute a recurring model for male figures, with almost literal takes, as in the terracottas of the 1970s, or more indirect but nevertheless always pregnant. Prehistoric shepherds, warriors and artisans are for Nivola mythical figures from the time of the nuraghi, who continue to roam the earth, giving continuous energy and inspiration to the artist.

“The relationship between prehistory and contemporary art is one of the key themes of twentieth-century culture,” concludes Giuliana Altea, president of the Nivola Foundation, “and Nivola’s work is an important testimony to this, never before studied in this aspect. The exhibition On the Shoulders of Giants, born out of the collaboration between the Mont’e Prama Foundation and the Nivola Foundation, confirms how synergy between institutions active in different cultural fields can give rise to outstanding results.”

“This project opens up a new avenue for what pertains to collaborative relationships and synergy between museum institutions, bringing history and the contemporary into dialogue, encouraging a fresh, plural and evocative integrated reading. We have included this programming among those that are fundamental for the current three-year period, gladly allocating the entire chapter earmarked for on-site exhibitions to this collaboration that is so intense and full of meaning, which by placing Cabras and Orani in close connection during the period in which the exhibitions will remain open at the same time, ideally connects all of Sardinia and its visitors,” says Anthony Muroni, president of the Mont’e Prama Foundation.

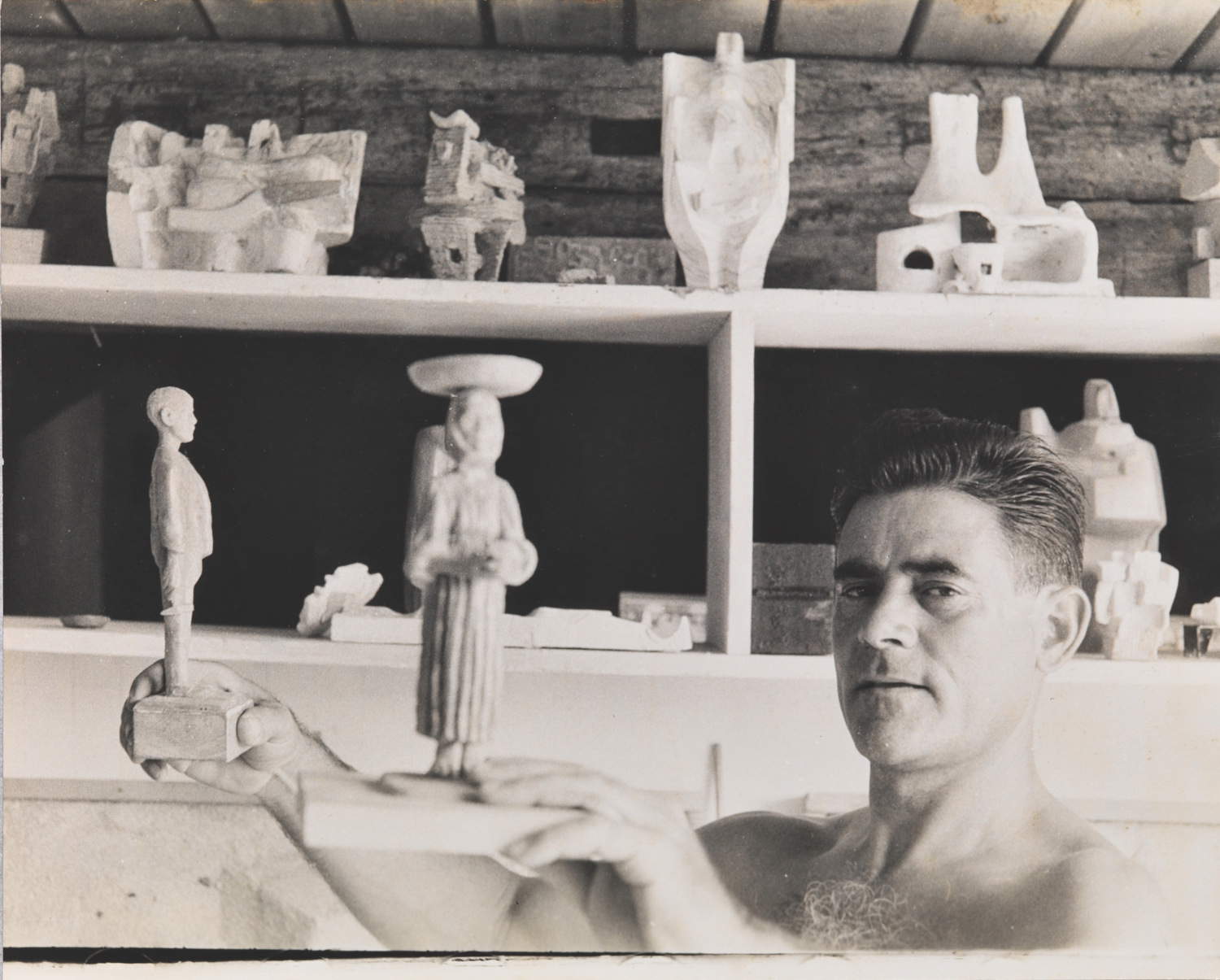

Image: Costantino Nivola with bronze portraits of his mother and brother Giuseppe, Springs, East Hampton, c. 1958

|

| Sardinia hosts first exhibition on the relationship between the art of Costantino Nivola and Sardinian prehistory |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.