Rome, at the Galleria Borghese the exhibition dedicated to Rubens

From November 14, 2023 to February 18, 2024, the Galleria Borghese in Rome is dedicating an exhibition to Pieter Paul Rubens ( Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640) entitled The Touch of Pygmalion. Rubens and Sculpture in Rome, curated by Francesca Cappelletti and Lucia Simonato. This is the second stage of RUBENS! The Birth of a European Painting, a major project carried out in collaboration with Fondazione Palazzo Te and Palazzo Ducale di Mantova that recounts the relationship between Italian culture and Europe through the eyes of the master of Baroque painting, and is also part of a broader research project of the Gallery dedicated to the moments when Rome was, in the early seventeenth century, a cosmopolitan city. The exhibition features more than 50 works from institutions such as the British Museum, the Louvre, the Met, the Morgan Library, the National Gallery in London, the National Gallery in Washington, the Prado, and the Rijksmusem in Amsterdam.

The aim of the exhibition is to emphasize Rubens’ extraordinary contribution, at the threshold of the Baroque, to a new conception of the antique and of the concepts of natural and imitation, focusing on the disruptive novelty of his style and how the study of models constitutes a further possibility for a new world of images. For this reason, the exhibition takes into account not only the Italian works that document his passionate and free study of ancient examples, but also his ability to reread Renaissance examples and engage with contemporaries, delving into new aspects and genres.

“A magnet for Northern European artists since the 16th century, Rubens’s Rome, between the Aldobrandini and Borghese pontificates, is the place to study the antique again, whose masterpieces of painting are beginning to be known, with the discovery in 1601 of the Aldobrandini Wedding,” stresses Francesca Cappelletti, Director of the Borghese Gallery and curator of the exhibition. “This is the moment of Annibale Carracci’s Farnese Gallery and Caravaggio’s Contarelli Chapel, about which a generation is stunned. Through the eyes of a young foreign painter like Peter Paul Rubens we look once again at the experience of elsewhere, we try to reconstruct the role of collecting, and of the Borghese collection in particular, as the engine of the new language of European naturalism, which unites the research of painters and sculptors in the first decades of the century.”

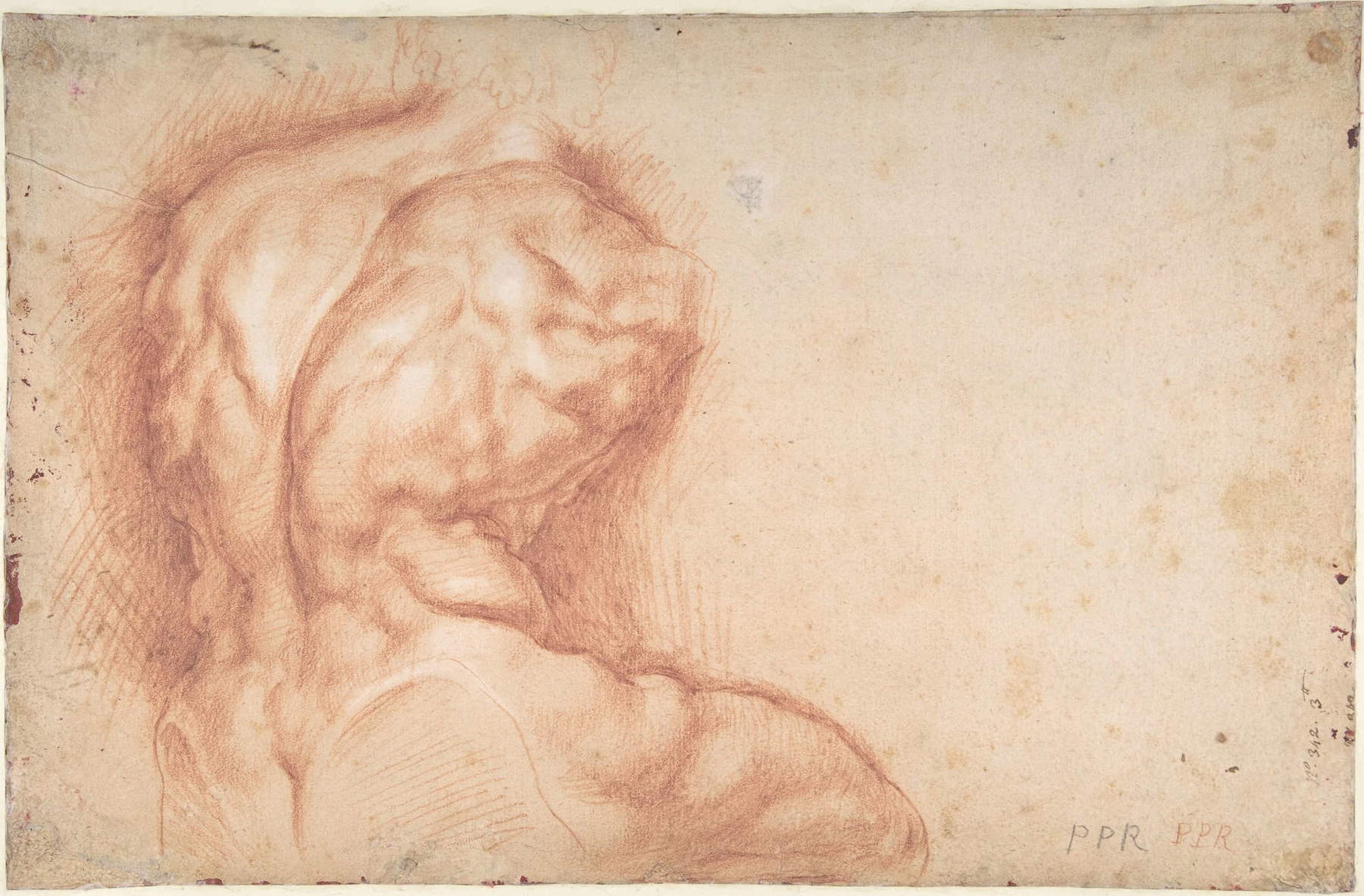

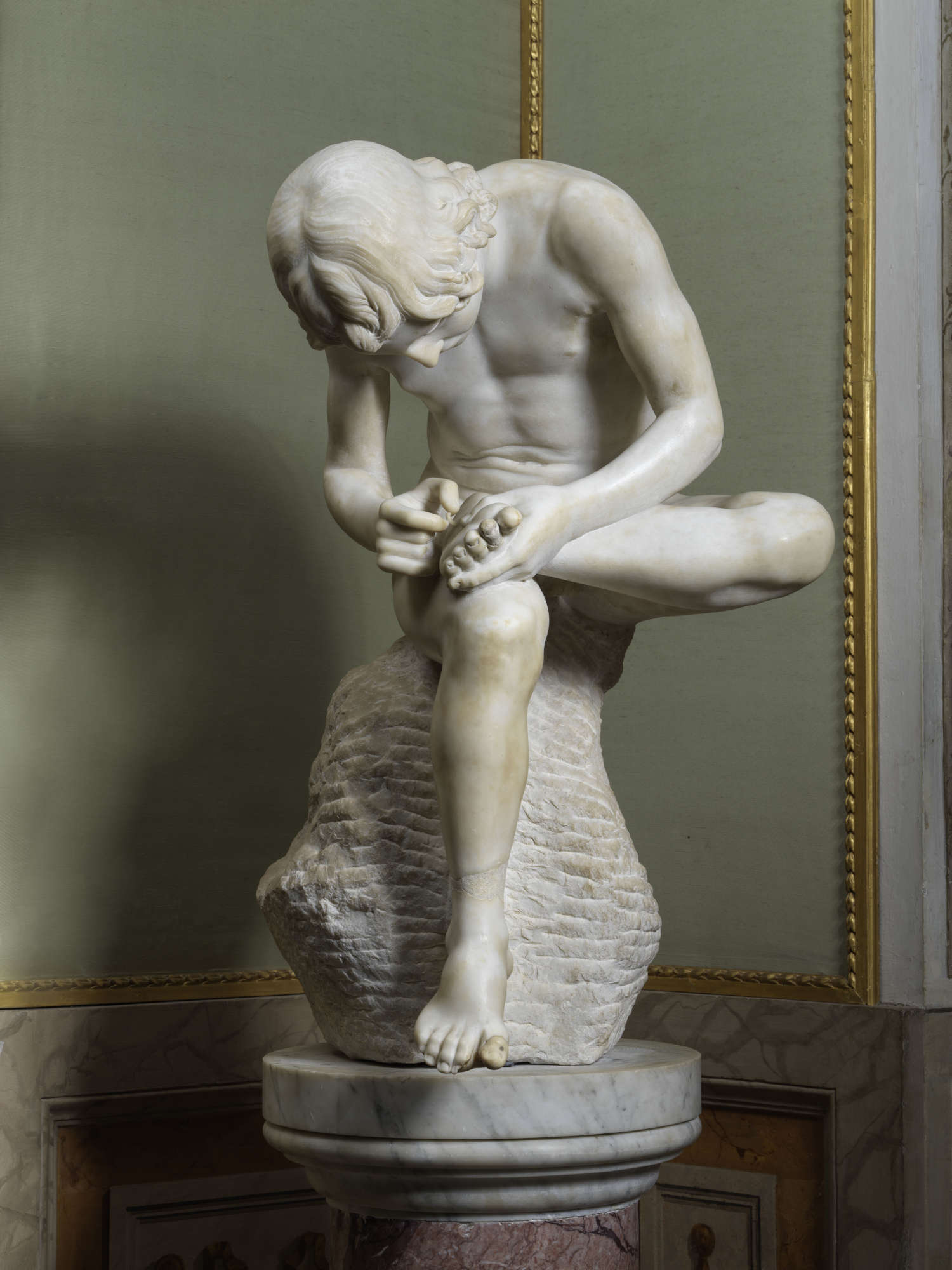

During the seventeenth century, Peter Paul Rubens was considered by contemporaries, such as the French scholar Claude Fabri de Peiresc and other literati of the République de Lettres, to be one of the greatest connoisseurs of Roman antiquities: nothing seemed to escape his powers of observation and his desire to interpret the ancient masters, and his drawings make the works he studied vibrant, adding movement and feeling to gestures and expressions. Rubens enacts in stories that process of vivifying the subject that he uses in portraiture. In this way, marbles, reliefs, and celebrated examples of Renaissance painting emerge enlivened from his brush, as do vestiges of the ancient world. A case in point is the famous statue of the Spinario, which Rubens draws, in sanguine, and then with red charcoal, taking the pose from two different viewpoints. In this way the drawing appears to be done by a living model instead of a statue, so much so that some scholars imagine that the painter used a boy posed like the sculpture. This process of animating the antique, though executed in the first decade of the century, seems to anticipate the moves of artists who, in the decades following his Roman passage, would be called Baroque.

How Rubens’ formal and iconographic insights filter into the rich and varied Roman world of the 1720s is an issue that has not yet been addressed systematically by studies. The presence in the city of painters and sculptors who had trained with him in Antwerp, such as Van Dyck and Georg Petel, or who had come into contact with his works in the course of their training, such as Duquesnoy and Sandrart, certainly ensured the accessibility of his models to a generation of Italian artists by then accustomed to confronting the Antique in the light of contemporary pictorial examples and on the basis of a renewed study of Nature. Among all, Bernini: his Bourgeois groups, made in the 1920s, reread famous ancient statues, such as the Apollo of the Belvedere, to give them movement and translate marble into flesh, as happens in the Rape of Proserpine.

“In this challenge between the two arts,” says Lucia Simonato, curator of the exhibition, “Rubens had to appear to Bernini as the champion of an extreme pictorial language with which to compare himself: for the intense study of nature and the depiction of motion and ’horses in levade’ suggested by the vincian graphics, which would also be addressed by the Neapolitan sculptor in his senile marbles with the same Leonardoesque ’fury of the brush’acknowledged by Bellori to the Antwerp master; finally also for his portraits, where the effigy seeks dialogue with the viewer, just as would happen in Bernini’s busts for which the felicitous expression of speaking likeness was coined.”

The exhibition The Touch of Pygmalion aims to illuminate the controversial relationship between Bernini’s masterpieces and Rubensian naturalism, as were other youthful sculptures by the artist, such as the Vatican Charity in the Tomb of Urban VIII, already judged by European travelers of the late eighteenth century to be ’a Flemish nanny.’ In this figurative context, the timely circulation of prints, taken from Rubensian graphic proofs, accelerated the dialogue throughout the 1730s, prompting publishing operations such as the Galleria Giustiniana, where ancient statues now definitively come to life, in accordance with an effect already defined as Pygmalion by critics.

The itinerary is divided into eight sections. The first, entitled The Myth of the Baroque, aims to introduce a general theme and at the same time a specific theme of the exhibition. Peter Paul Rubens was, according to last century’s art historian Giuliano Briganti, the ’spiritual father’ of those Italian artists, including Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose works had supported the majesty of the papacy of Urban VIII (1623-1644). Coined just over two centuries ago to denote the art of those years (but not only), the label ’Baroque’ still eludes unambiguous definition in studies. At the origin of the birth of such a new and disruptive figurative language, which would animate Europe for almost one hundred and fifty years until the arrival of the neoclassical season, must be placed Rubens himself. Rubens’ was a ’formal’ revolution, but it also represented the beginning of a new iconographic codification of mythological and historical subjects, starting with a careful reinterpretation of the Italian Renaissance heritage and again of ancient statuary. Rubens was able to breathe new life into ancient myth, but without ever losing sight of the reality of the present in which he was living.

The second section, Rubens and History, traces the relationship between Rubens and history and takes the audience to Rome, where the artist passionately studied the so-called dying Seneca, a sculpture in chalky marble (now in the Louvre, formerly in the Borghese collection), which was believed to stage the philosopher’s suicide described by Tacitus, and finally depicts the philosopher’s death in pictorial works that turn bourgeois marble into flesh. But ancient history is not just a literary subject for Rubens. It is also an ongoing exegetical exercise of the iconographies and objects that attest to the customs of the Romans and Greeks. With the erudite Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc he investigates them in rich correspondence exchanges: episodes described by ancient historians are transformed by Rubens into paintings and tapestries, where armor, crests, shields, footwear and insignia are restored with antiquarian accuracy. Finally, with its moral authority, ancient history also allows Rubens to comment on the present.

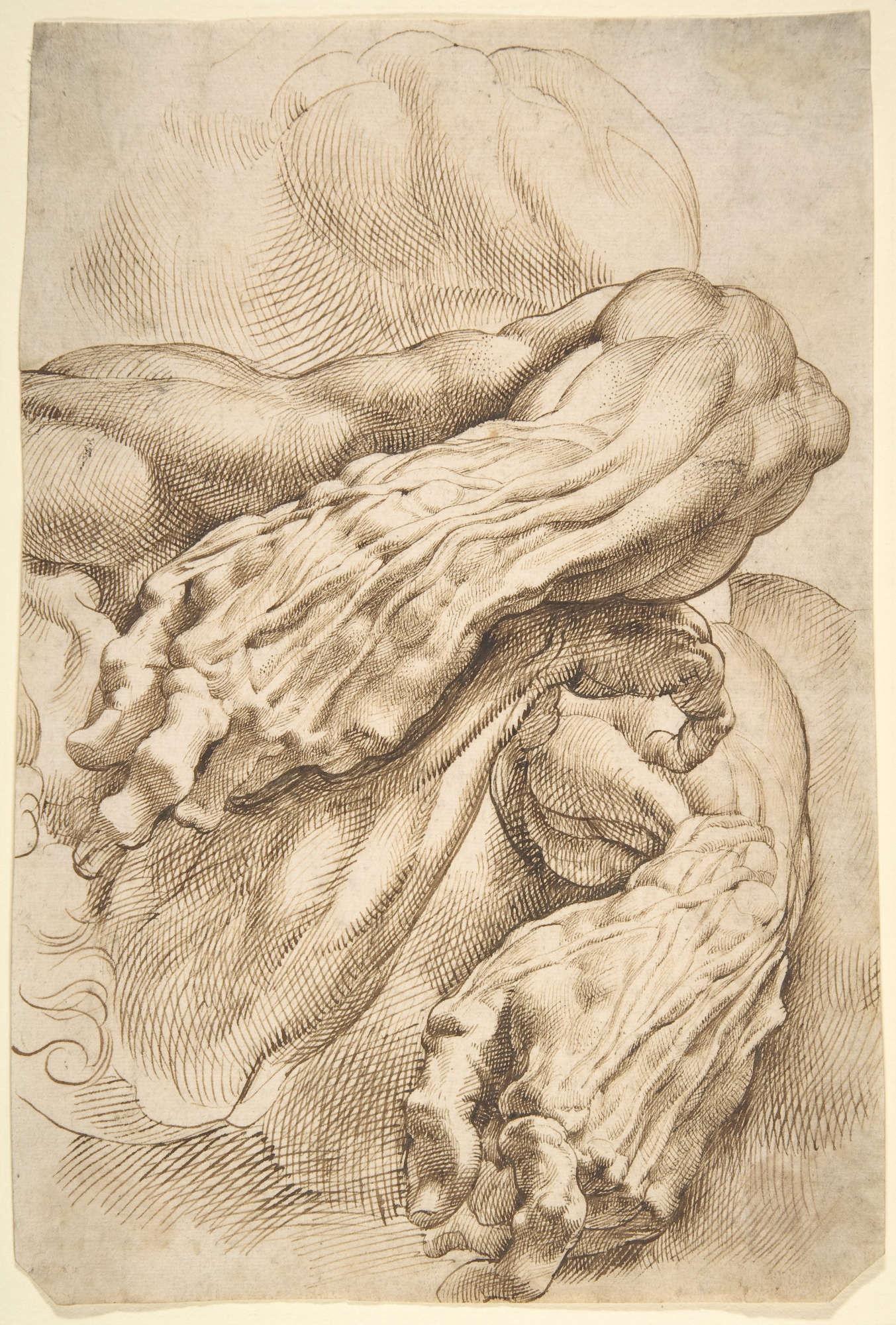

The third section, Dramatic Bodies, explores the grammar of the human body in Rubens: studied from life, investigated from Antiquity, and interpreted in the light of the lessons of the Renaissance masters. A few names stand out in importance. First and foremost, Michelangelo: an artist already dear to northern European Mannerists such as Hendrick Goltzius, well known to Rubens before his trip to Italy. For anatomical investigation, however, and for motion, Rubens’ attention is entirely on Leonardo, discovered ex novo by the artist during a brief stay in Madrid (1603-1604) made during his formative trip to Italy. In Spain Rubens probably had access to Leonardo’s drawings still in the hands of the sculptor Pompeo Leoni and studied them avidly. In his Hercules Strangling the Nemean Lion in the Louvre, the Michelangelesque muscular exertion of the hero is unthinkable without Leonardo’s lesson on strength and already preludes Bernini’s torsions, which would later be those of Baroque sculpture. Instead, the fourth section is entitled Statuary Bodies : Joachim von Sandrart, a German pupil of Rubens, emphasizes in his treatise on art published in the late seventeenth century, the Teutsche Academie, the need for painters to bring out the figures, to give roundness to their contours and depth to the space they inhabit. For the Flemish master, and for the many artists who followed his example, the study of ancient statuary and reliefs was not only an opportunity to discover previously unseen mythological subjects, investigate the customs of the Romans, and copy muscular human anatomies, but was first and foremost a way to learn how to accord the forms of painting new statuary vigor, to literally give body to its protagonists and make them stand out as living figures within the composition.

Then there is a Rubens and Caravaggio section, devoted to the relationship between the two great artists. In fact, it was Rubens who insisted that Vincenzo Gonzaga purchase the controversial Death of the Virgin, now in the Louvre, which Caravaggio had executed for Santa Maria della Scala in 1605. Some ’connoisseurs’ of art, capable of looking beyond the work’s function and its place of destination, noticed the painting’s extraordinary novelty, that still beauty and ability to make religious history new and present deployed by Caravaggio. Rubens had suggested to his patron not only an extraordinary painting for his gallery, but also a rare and incisive gesture: using an altar painting for a space dedicated to art and not to devotion and completely changing the destination of a ’public’ work. The same, almost at the same time, Scipione Borghese would do by buying from the confraternity of the Palafrenieri Caravaggio’s Madonna and Child with St. Anne still in the room that houses this section. Rubens’ interest in Caravaggio is also measured in a more specifically artistic realm; in Rome Peter Paul not only draws from Antiquity and the great masters, but also from his contemporaries and, with particular interest, from Caravaggio and his Deposition in the Sepulchre, the altarpiece for the Vittrice Chapel in the Chiesa Nuova, now in the Vatican Museums, executed between 1601 and 1602. If Rubens could be accused of excessive naturalism, even in his inventive eagerness, certainly the monumental realism of which Caravaggio has always been understood as the leader appears quite different. His paintings were considered “without action”: the luminous contrasts nailed his protagonists to a precise moment in their (and our) existence.

The sixth section is entitled The Birth of Pictorial Sculpture. Bernini’s female statues resembled ’Flemish nannies’ to travelers arriving in Rome from northern Europe in the late 18th century, according to whom there was no doubt that some formal affinity ran between Rubens and the Italian sculptor. Pluto’s hands sunk into Proserpine’s flesh were evidence of ’Flemishness,’ according to the German writer August Wilhelm von Schlegel. In having competed with painting in themes and forms, in adherence to the natural datum and in expressiveness, Bernini’s sculpture was accused of having overstepped its proper boundaries and become ’pictorial’: an expression that would be raised to a category of art history by the critic Heinrich Wölfflin at the end of the nineteenth century. In many ways at the very origin of the definition of the Baroque, the relationship between Rubens and Bernini continues to remain elusive in studies. We do know that in the 1730s, while staying with his second wife Helena Fourment on the estate of Het Steen near Antwerp, the painter wasted no opportunity to inquire about what was going on in Italy, where Bernini had just erected the Baldachin of St. Peter’s and was the artist of choice for Urban VIII. For Rubens, attention to sculpture is not only an antiquarian issue, but also involves the study of very different plastic objects: modern as ancient, marble as metal, statuary as numismatic. More complex is to understand how Bernini approaches in the 1920s, while at work on the bourgeois groups, the Rubensian innovations. In this challenge between the two arts, the Flemish artist had to appear to the Italian sculptor as the champion of an extreme pictorial language with which to compare himself.

We then come to the seventh section, entitled The Touch of Pygmalion, where by ’the touch of Pygmalion,’ the mythical sculptor who obtained life from the gods for one of his statues with which he had fallen in love, is meant Rubens’s ability to transform in his drawings and panels the inert ancient marble into vibrant pictorial matter. In two fundamental Latin pages of his fragmentary treatise On the Imitation of Statues, the Flemish artist explains how this ’transmedia’ process, or transposition of formal values from sculpture to painting, takes place. First and foremost to be avoided was slavish imitation of the ancient model, which would lead to the depiction of painted statues instead of subjects taken from life. The advice is put into practice by Rubens exemplarily in his graphic proofs, where in order to translate marble into flesh he insists on the so-called “maccaturae”: the soft folds of the skin of both men and animals (as in the neck of the Farnese Bull depicted by the artist in black pencil), accentuating which the figure appears alive and uncarved. The Antique from which Rubens takes his starting point is actually already vital. These are fragments that have been supplemented by major interpretive restorations (as in the case of the dying Seneca) and sometimes even modern copies that derive from the Antique, such as the Spinario, now in the Galleria Borghese: a late sixteenth-century statue, more accessible in the seventeenth century than the famous Capitoline bronze.

Finally last section is the one on Rubens and Titian: during his stay at the Spanish court, between 1628 and 1629, Rubens made numerous copies from Titian, a painter he never tired of observing, in his travels to discover Italy in the first decade and whenever he could get the chance. In the room where this section is housed, the Amorsacro e Amor profano, Titian’s early masterpiece, and Venusblindfolding love, among the artist’s other paintings, make immediately understandable one of the reasons why Scipione Borghese’s collection was intensely visited by artists.

The exhibition opens Tuesday through Sunday with hours 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. (last admission 5:45 p.m.). Closed every Monday. The visit lasts two hours and entrance shifts are every hour. Tickets: full 13 euros, reduced 18-25 2 euros. For info: https://galleriaborghese.beniculturali.it/

|

| Rome, at the Galleria Borghese the exhibition dedicated to Rubens |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.