On view until May 13, 2018 (it opened last December 12) is the exhibition Revolutija. From Chagall to Malevich, from Repin to Kandinsky, in the halls of MAMbo - Museum of Modern Art in Bologna: an important in-depth look at the art of the Russian avant-garde in the period between 1910 and 1920, one of the fundamental moments in the history of twentieth-century art. With seventy works arriving from the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg, including masterpieces by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Marc Chagall, Natalja Goncharova, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Ilya Repin, Valentin Serov and Nathan Altman, the Bologna exhibition aims to provide a broad account of the modernity of the cultural movements that developed in Russia in the early twentieth century, from primitivism to Cubofuturism, from Suprematism to Constructivism. These were experiences destined to radically influence 20th-century art, but their legacy is still felt today.

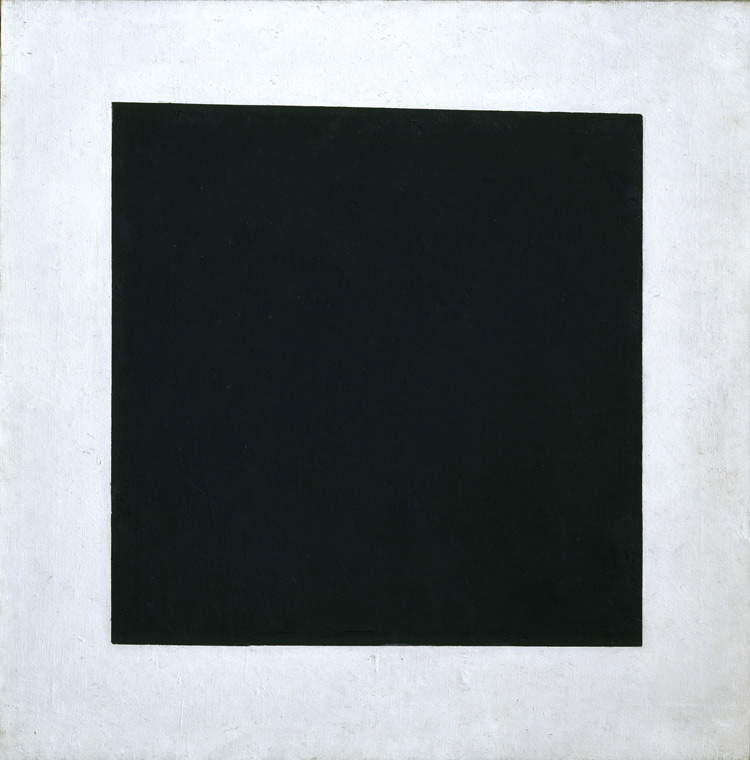

The narrative starts with Ilya Repin’s October 17, 1905, painting documenting the beginning of the 1905 Revolution: the uprising, suppressed by Tsar Nicholas II, was not only the prologue to the decisive revolution of 1917, but in the field of art it sanctioned the end of realism. The avant-garde emerged during this period: among the first to develop a new language were Michail Larionov and his wife Natalja Goncharova, who looked to Italian futurism and French cubism to give birth to raggism. In the exhibition, the public will be able to admire Natalja Goncharova’s celebrated Cyclist: as scornfully as the Russian painter had defined Italian futurism as "an emotional impressionism," the derivation of her Cyclist from the works of her Italian colleagues is clear. Artists such as Larionov and Kandinsky ushered in a painting capable of detaching itself from the representation of objects (Kandinsky, in particular, was the first abstract artist in the history of art), and paved the way for the fundamental researches of Malevich, who by founding Suprematism had proclaimed, in 1917, the supremacy of pure sensibility over all forms of realistic representation. Works such as Black Square, Red Square, Black Cross and Black Circle, with the reduction of art to the representation of pure elements, are clear examples of his art.

The turning point was probably marked in Petrograd on December 19, 1915 at a major exhibition entitled 010, where Malevich and Aleksandr Tatlin, then the leading exponents of the Russian avant-garde, exhibited, effectively dividing the art scene into two factions because of their differences in artistic conceptions. Thus, if Malevich favored pure forms such as the square or the circle in order to aspire to an art that would definitively transcend reality, Tatlin believed that art was a research on the abstract properties of surfaces and colors to be put, however, at the service of concrete needs (for Tatlin and his supporters, art as such was a mere bourgeois aestheticism to be overcome: every artistic form had to be useful to society): his constructivism therefore sought to combine art with architecture, design, advertising, and industry. His idea of art was so successful that Majakovsky said that “for the first time, a new word in art, constructivism, came not from France, but from Russia” and that constructivism influenced Russian art for decades.

The exhibition then goes on to investigate the circumstances that gave rise to socialist realism, represented by artists such as Isaak Brodsky and Wassily Kuptsov: the latter is featured in the exhibition with his work Maksim Gor’kij, which depicts the well-known Tupolev ANT-20 aircraft massively used for Stalinist propaganda. But the Bologna exhibition also allows the public to discover how important the role of women artists was for the Russian avant-garde: not only Natalja Goncharova, but also painters such as Olga Rozanova, Sofja Dymsits-Tolstaja, Vera Muchina and Zinaida Serebrjakova made fundamental contributions to developments in art between 1910 and 1920. The expiration of socialist realism into an art that rejected any modern research and aimed to innovate the language of art, in parallel with the growth of power in the hands of Stalin, ended the heyday of 20th-century Russian art, as well as the period that Revolutija aims to investigate.

The exhibition is open daily (except Mondays, which are closed) from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays until 8 p.m. The box office closes an hour earlier. Rates: €14 full, €12 reduced (over 65, students up to 26, disabled, journalists, law enforcement, TCI members, Bologna Welcome Card, Club Skira, Coop Alleanza 3.0), €10 reduced for groups and tour guides accompanying a group, €5 reduced for schoolchildren, €3 reduced for preschools, €7 for Card Musei Metropolitani Bologna holders, €8 for children between 6 and 17. University students get in at a cost of 9 euros every Tuesday. Also available is the open ticket without date at a cost of 16 euros plus 1.50 presale. Still, there is a 2-for-1 promotion for Cartafreccia members who reach Bologna by Frecce or Intercity. Free for children under 6 years of age, one companion for disabled, accredited journalists, one companion per group of adults, two companions for school groups. Family offers are also planned (18 euros adult + child, 26 euros adult + 2 children, children between the ages of 6 and 14). More information can be found at www.mostrarevolutija.it.

Below is a selection of the works (all housed at the ©State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg):

|

| Ilya Repin, October 17, 1905, oil on canvas, 1910 |

|

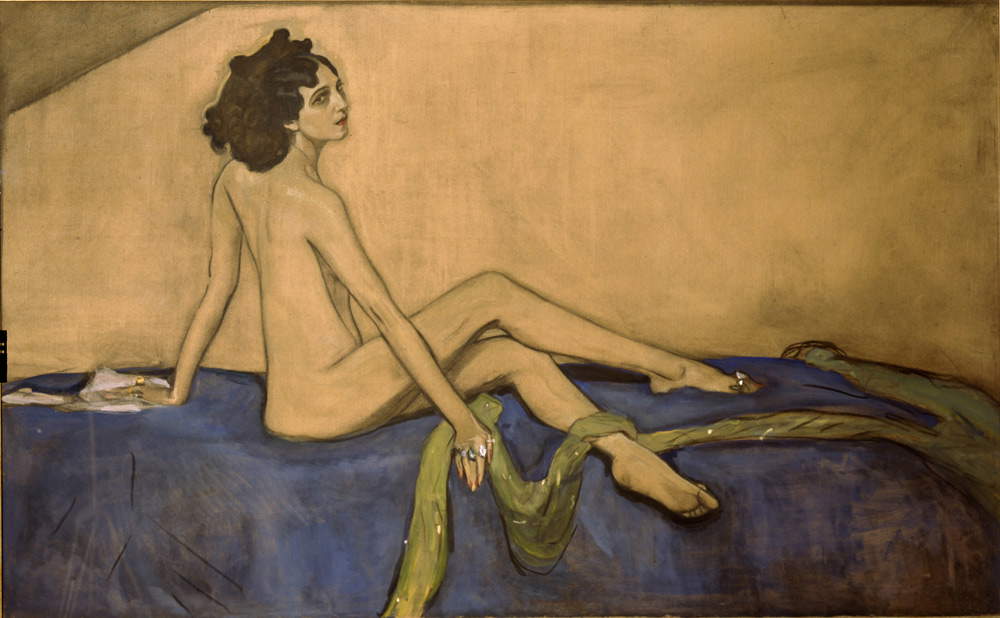

| Valentin Serov, Ida Rubintein, oil and charcoal on canvas, 1910 |

|

| Natalja Goncarova, Cyclist, oil on canvas, 1913 |

|

| Nathan Alrman, Portrait of Anna Achmatova, oil on canvas, 1915 |

|

| Marc Chagall, The Walk, oil on canvas, 1917-1918 |

|

| Wassily Kandinsky, On White (I), oil on canvas, 1920 |

|

| Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, oil on canvas, 1923 |

|

| Revolutija, from Chagall to Kandinsky Russian avant-gardes on display in Bologna. Here is a selection of images |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.