The Fondazione Palazzo Blu in Pisa announces for this fall its major exhibition dedicated to the Macchiaioli: from October 8, 2022 to February 26, 2023, the Pisan museum venue will in fact present a retrospective entitled I Macchiaioli, curated by Francesca Dini, an art historian and one of the most authoritative experts on this movement, produced and organized by Fondazione Palazzo Blu and MondoMostre, with the contribution of Fondazione Pisa.

Through more than 130 works, mostly from private collections, but also from important museum institutions such as the Uffizi Galleries, the Museum of Science and Technology in Milan, the Gallery of Modern Art in Genoa and the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome, the exhibition aims to trace the evolution and revolution of the Macchiaioli in the second half of the 19th century.

This important painting movement became popular, reaching a wider audience, more than 50 years ago thanks to the now historic exhibition at Forte Belvedere in Florence. Much has been said and portrayed about the art of the Macchiaioli, but without ever being able to fully restore the international visibility it deserves. This is mainly because the competition with FrenchImpressionism, set as inescapable by critics since the time of Roberto Longhi, has often prevented a complete and autonomous reading of the Macchiaioli story. Today more than ever, having dropped nationalist views in favor of a Europeanist and international outlook, we are more inclined to dilute the Franco-centric conception of the history of 19th-century European painting and, without diminishing the universal scope of the Impressionist message, to highlight with greater objectivity the vital links of cultural dialogue among the peoples who contributed to the evolution of European civilization.

In this context the story of the Macchiaioli takes on an even more interesting relevance, as does Tuscany, the land of choice for their artistic experience. These painters thus appear for what they actually were, namely the key to an open, purposeful, honest and bold dialogue with the most important artistic communities of Europe at the time.

The term “Macchiaioli” was coined in 1862 by an anonymous reviewer of the Gazzetta del Popolo, who thus defined those painters who around 1855 had given rise to an anti-academic renewal of Italian painting in the realist sense. The meaning was obviously derogatory and played on a particular double meaning: in fact, to give oneself to the bush means to act furtively, illegally. This revolution, apparently highly original, had instead deep origins in the figurative art of the peninsula. The same term “macchia” had been used by Giorgio Vasari about the mature works of Titian Vecellio, which were “conducted with blows, pulled off roughly, and with stains of manner, which from near cannot be seen, and from afar appear perfect.”

Starting from the elaboration of the principles of European realism formulated by Gustave Courbet and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and perfecting the expressive tool of the “macchia” taken from the example of the Venetian sixteenth-century painters, the Macchiaioli ventured on the path of light, painting their contemporary reality in the simplicity of the natural scenery of which they had direct experience - in Venice, La Spezia, Castiglioncello, Piagentina, to name but a few symbolic places of the movement - in the poignancy of the ethical and moral values of a glorious epoch, the Risorgimento, which permeates the high formal tightness of their masterpieces.

Divided into eleven sections, the exhibition at Palazzo Blu will tell the story of the adventure of a group of progressive young painters, Tuscan and otherwise, who, eager to distance themselves from the academic institution in which they had been trained, under the influence of important masters of Romanticism such as Giuseppe Bezzuoli and Francesco Hayez, came to write one of the most poetic and daring pages in the history of art, not only Italian. The key works of this movement will be exhibited, with the aim of cadencing the different moments of the Macchiaioli’s research, their confrontation with other artists and with the different European schools of painting; their bewilderments, their ability to collectively question themselves and to continue on the road of progress and modernity without ever abandoning the highroad of light. Visitors will find at Palazzo Blu the answers to the most recurring questions: why were the Macchiaioli born in Tuscany? Can they consider themselves the painters of the Risorgimento? Why are they considered a European avant-garde?

The narrative starts, in the first section, from the Florentine Caffè Michelangelo, in which the Tuscans Telemaco Signorini, Odoardo Borrani, Raffaello Sernesi, Giovanni Fattori, Adriano Cecioni, Cristiano Banti, and Serafino De Tivoli landed in 1855, joined by the Neapolitan Giuseppe Abbati, the Venetians Vincenzo Cabianca and Federico Zandomeneghi, the Ferrara-born Giovanni Boldini, the Romagna-born Silvestro Lega, the Pesaro-born Vito D’Ancona, and the Roman Nino Costa. Among their supporters were the poet Giosuè Carducci, the critic Diego Martelli, and the engineer and man of science Gustavo Uzielli. These artists who call themselves “progressives” challenge the academy of fine arts as a system and defend freedom of expression. Their goal is to get to express their current feeling of young men animated by deep patriotic and artistic ideals through more modern and shared art forms. They want to confront realities other than the Italian one and welcome those who, even if only passing through Tuscany, can bring some stimulus, among them Edgar Degas and Gustave Moreau, Marcellin Desboutin and the writer Georges Lafenestre, Auguste Gendron (Delaroche’s pupil), the American Elihu Vedder.

The exhibition continues through the changes of scenery, beginning with the 1855 Universal Exhibition in Paris, which sanctioned the triumph of modern French landscape painting, and also changed the outlook on landscape of some painters, led by De Tivoli and Charles Markò Jr. On his return from Paris De Tivoli began to devote himself to the study of the real, achieving admirable effects of naturalness and atmospheric airiness, as in La questua.

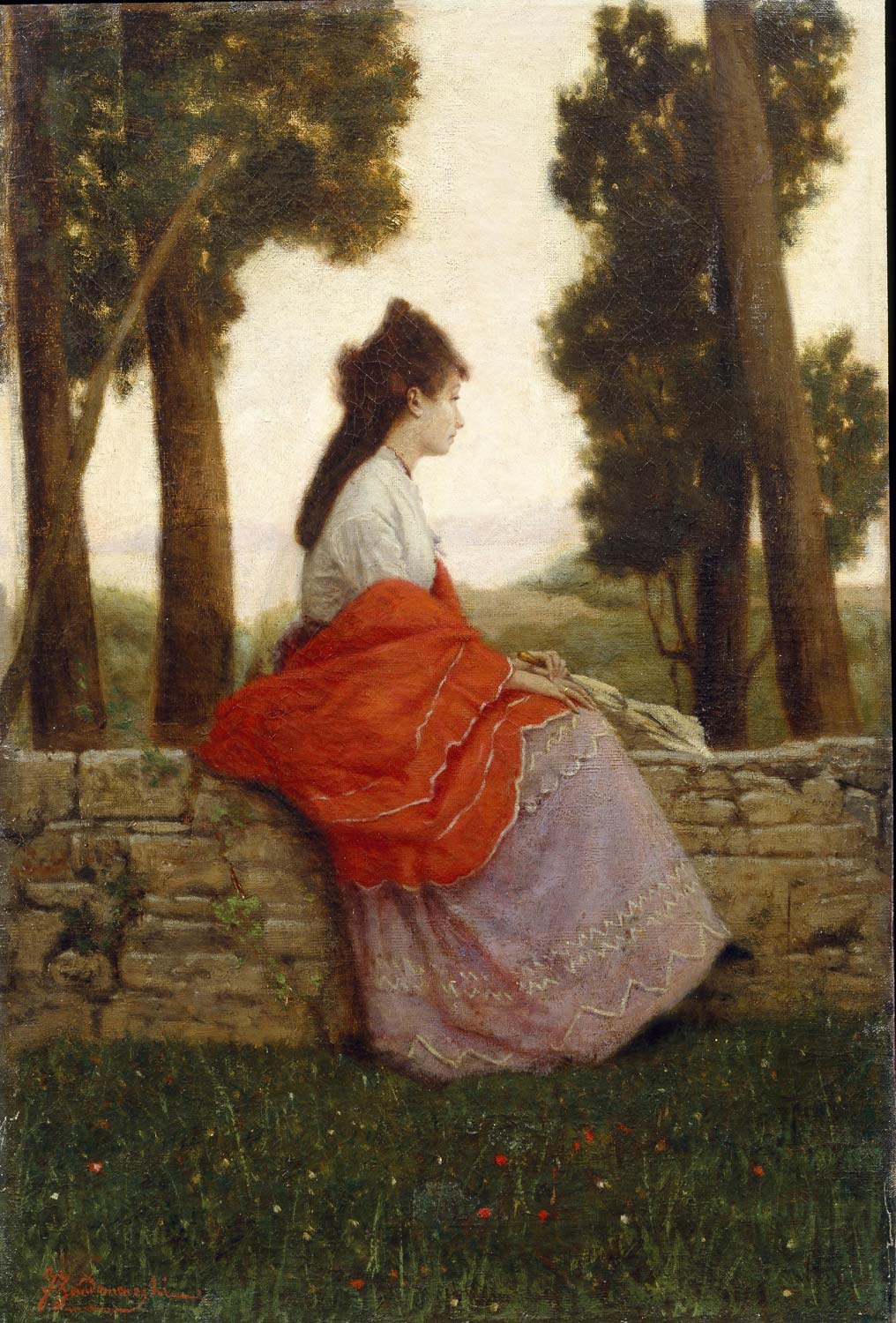

The gaze also changes on contemporary reality, and even figure painters like the Veronese Cabianca find themselves looking at contemporary society with new eyes, moving from the timid realism of interior scenes to a work like L’abbandonata, in which Cabianca boldly captures the emotional state of the protagonist with unusual determination.

Also on display is the theme of the Second War of Independence, which provokes the Tuscan progressives’ path to reflect on their particular relationship with the Risorgimento epic. Meanwhile, encouraged by the historical moment, Giovanni Fattori also “turned to the bush” who, in the Battle of Magenta, painted a large choral fresco in which the decisive Italian victory for the fate of the war, with the liberation of Milan, became a humanitarian event.

The fifth section is devoted to Cabianca’s painting The Morning, in Pisa for the first time in 160 years, successfully exhibited at the Promotrice di Torino in 1861. The exhibition continues with an account of the success the Macchiaioli had after the Turin exhibition, the years of affirmation of their art. At this time extraordinary masterpieces such as Reaping the Wheat in the Mountains of San Marcello by Borrani, Pastura in the Mountains and Tetti al sole by Sernesi, and Contadina nel bosco by Fattori were born. The group is now cohesive and strong thanks to a common project, namely to contribute to the birth of a national art, aligned with the most advanced manifestations of European painting.

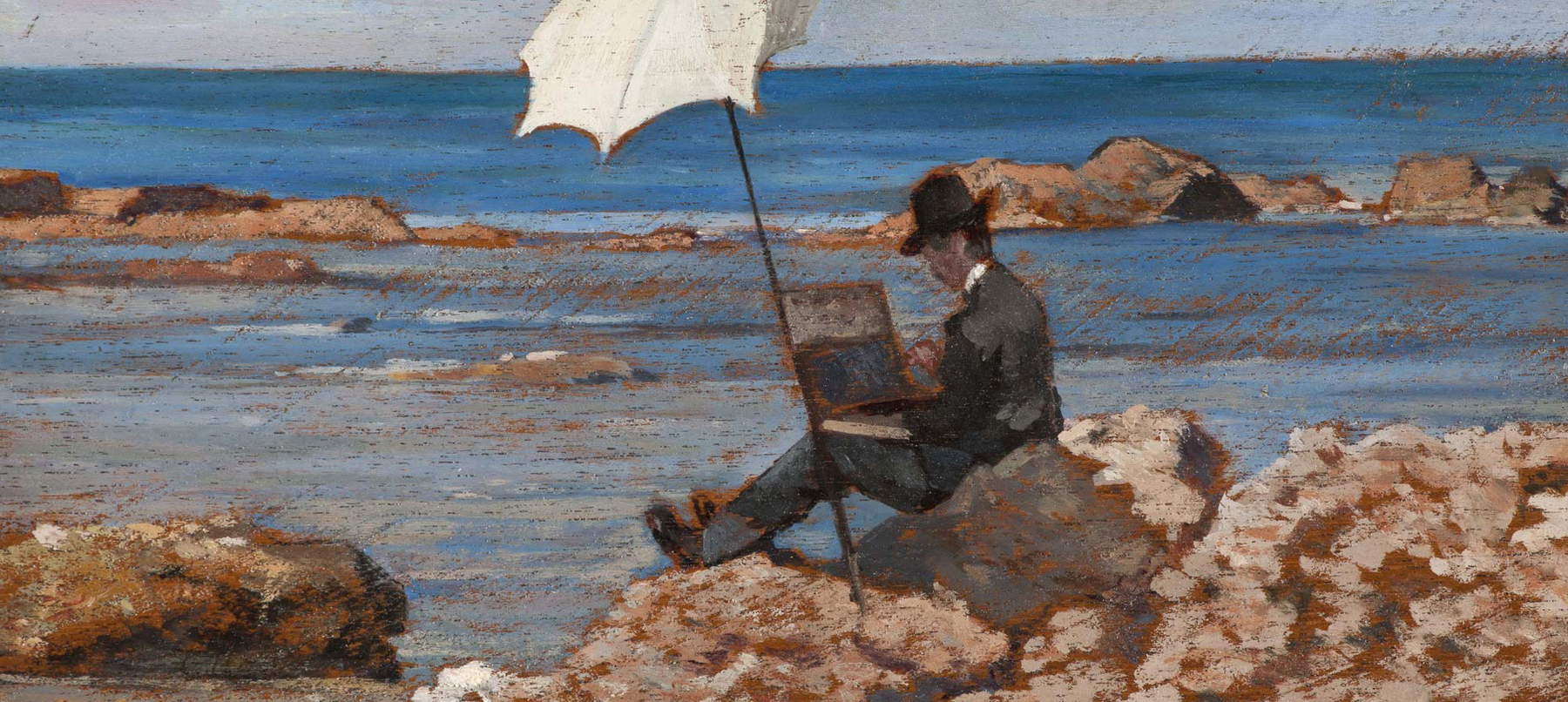

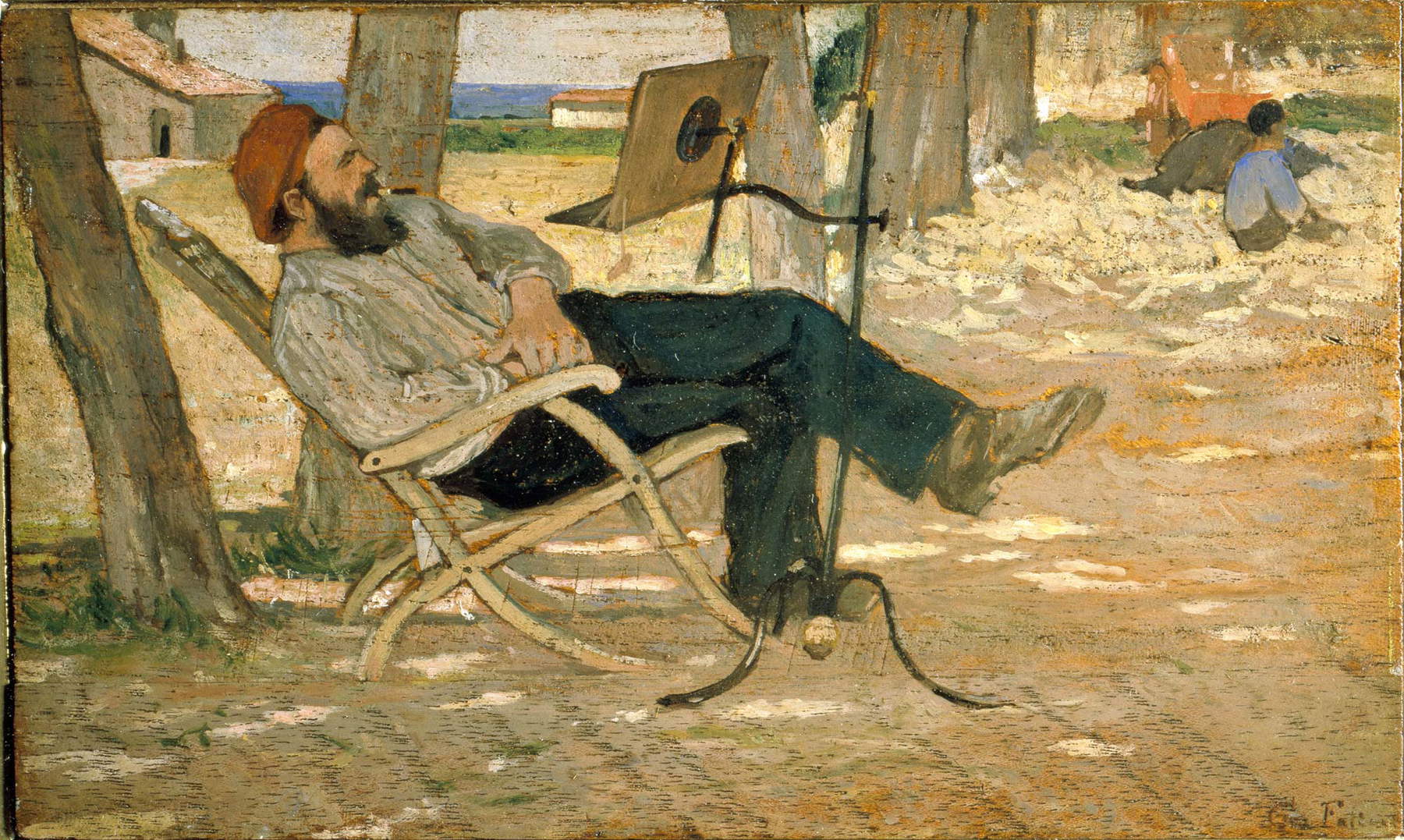

The next sections traverse the evocative places and atmospheres of Liguria, upper Tuscany and Castiglioncello, a hitherto unknown locality, where the Macchiaioli arrive at an expressive essentiality that finds in the unspoiled nature of that place a fundamental poetic counterpart. Hence some great works such as Borrani’s enameled predellas, such as Casa e marina a Castiglioncello and Case di Pannocchio; Fattori’s admirable syntheses; Abbati’s silvery visions, such as Marina a Castiglioncello, Casa sul botro, and Bimbi a Castiglioncello; and Sernesi’s sunny depths, such as Marina a Castiglioncello. Factor’s production of these years happily balances two different intonations, the elegiac one of masterpieces such as La raccolta del fieno in Maremma, Le Macchiaiole, Rappezzatori di reti a Castiglioncello and Criniere al vento and the prodigious synthesis of jewels such as Bifolco e buoi, Ritratto di Valerio Biondi and Diego Martelli a Castiglioncello, Lega che dipinge sugli scogli, small plates in which reality is transposed into pure and essential pictorial values.

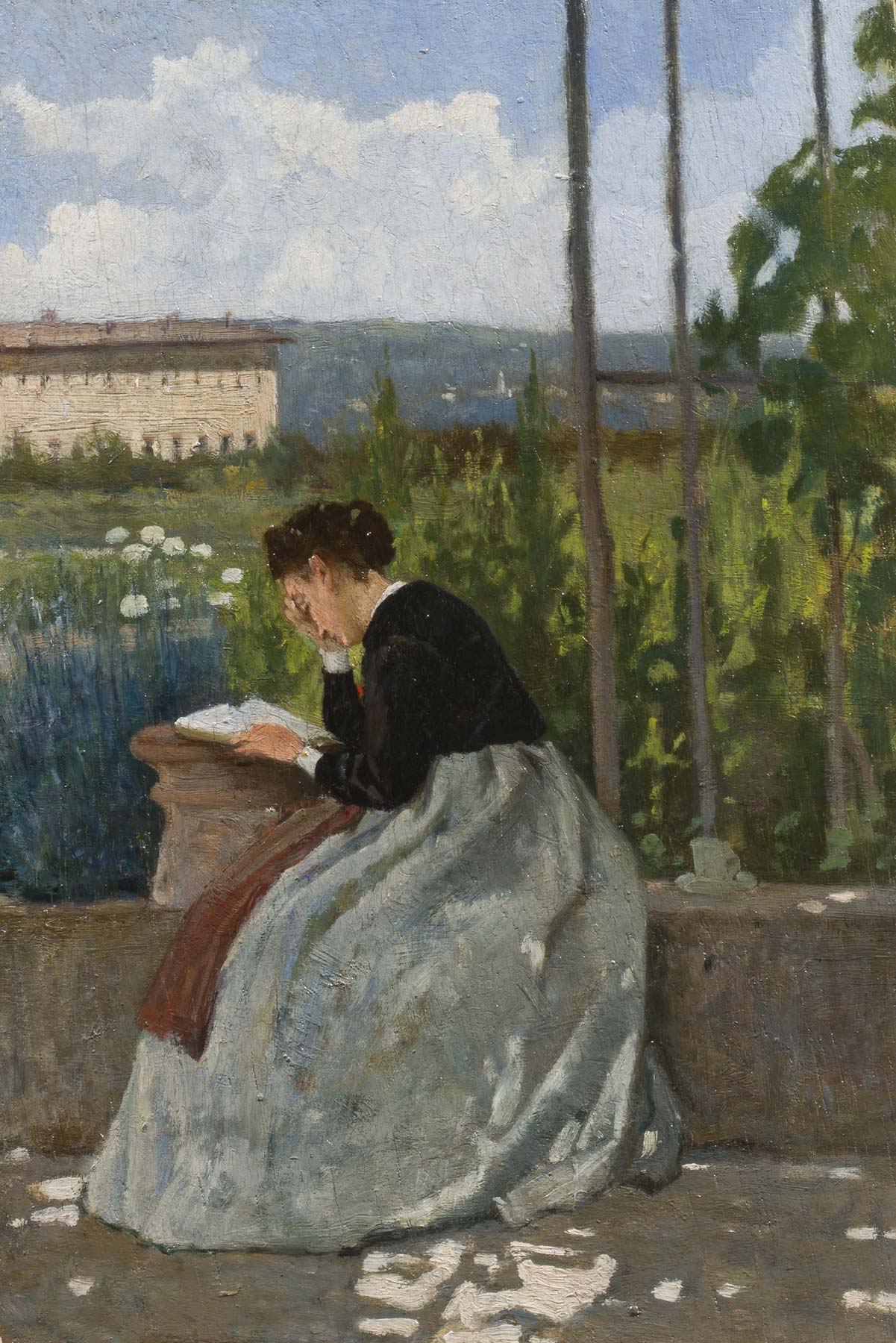

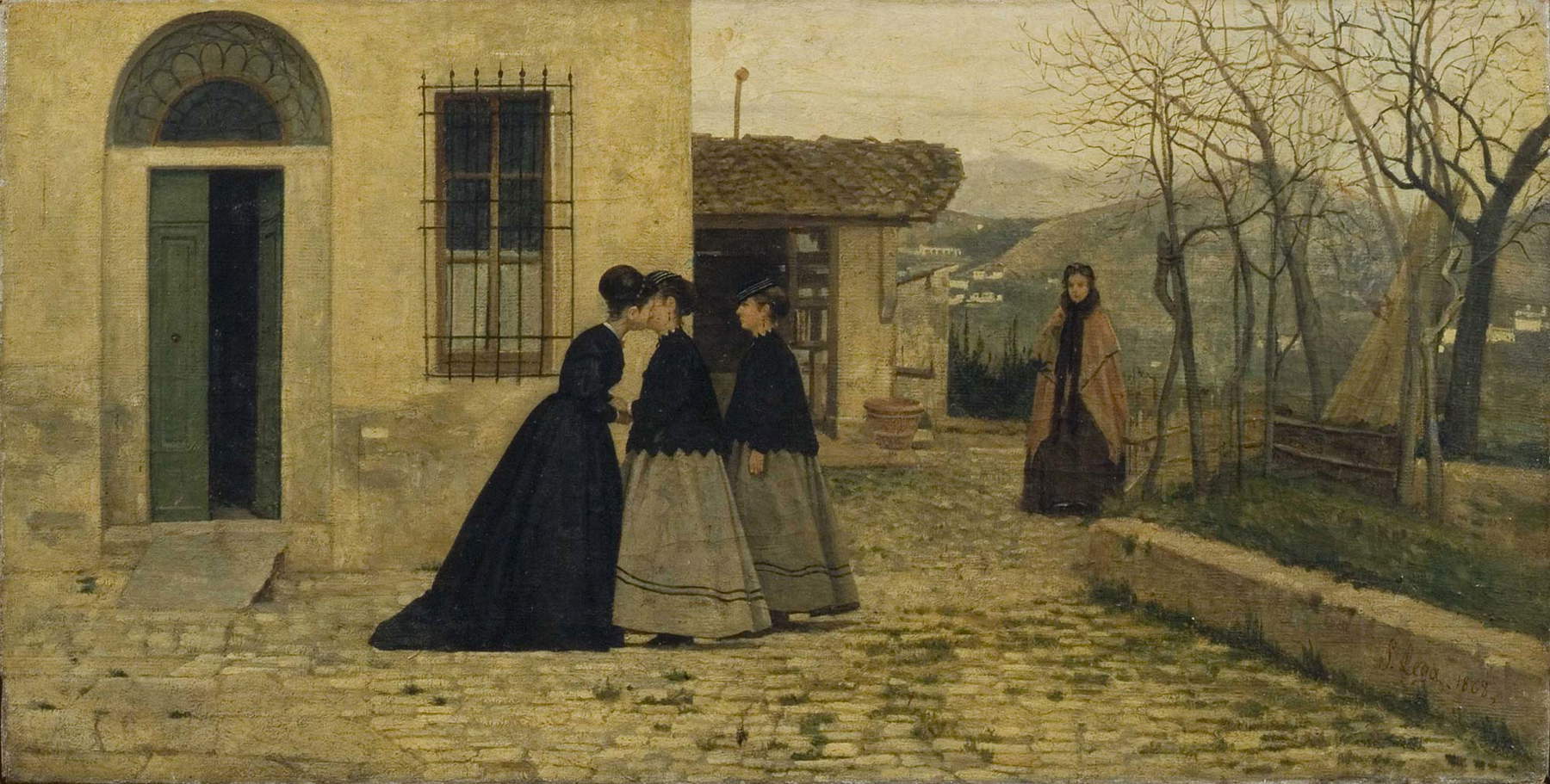

Another important place where the painters congregate is the Florentine countryside of Piagentina, where the luminous intonation is less wild, more inclined to go along with the quiet atmosphere and domestic intimacy. Lega is the cantor of the affectionate and serene atmosphere of Piagentina: in the masterpieces produced by the Modiglianese artist in these years, from La visita to La visita in villa, from Lettura romantica to L’educazione al lavoro, we find that unity of inspiration that gives the painter’s work the melodic continuity of the same elegiac song.

At the end of 1866, the Caffè Michelangelo closed its doors, and in January 1867 the first issue of the Gazzettino delle arti del disegno, founded and directed by Diego Martelli, came out: the critic created the magazine as a “media” place, replacing the physical place. The aim is to investigate personalities and ideas that are not exclusively Italian and to open a debate of a European nature. An attempt, that of the Gazzettino, which entrusted solely to Martelli’s financial forces is destined, however, to be short-lived. In this section it is possible to admire an unprecedented comparison between Michele Gordigiani’s Portrait of Princess Margherita of Savoy, “courtly” and modern at the same time, and Giovanni Boldini’s more “formal” Portrait of a Russian Lady.

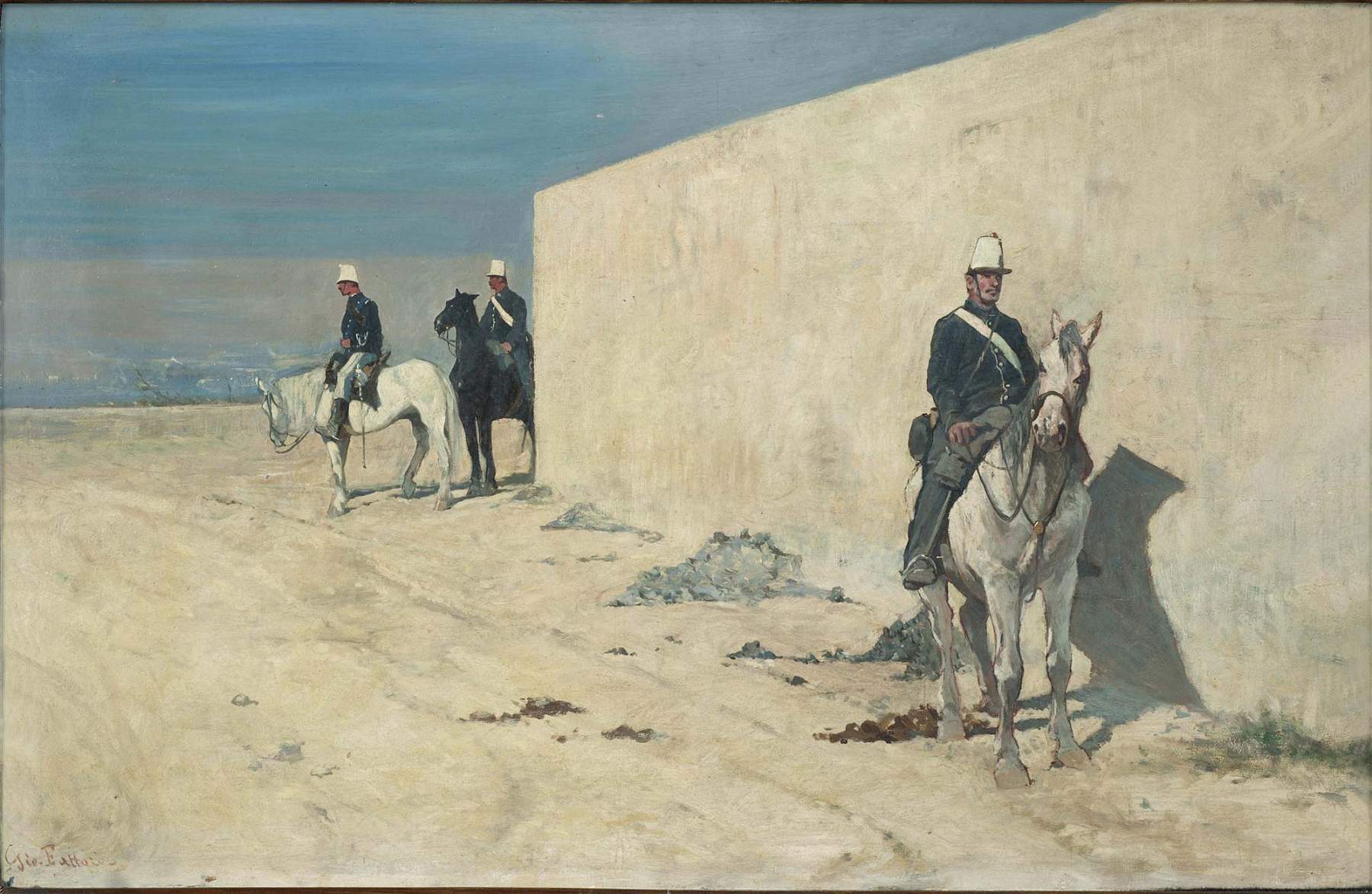

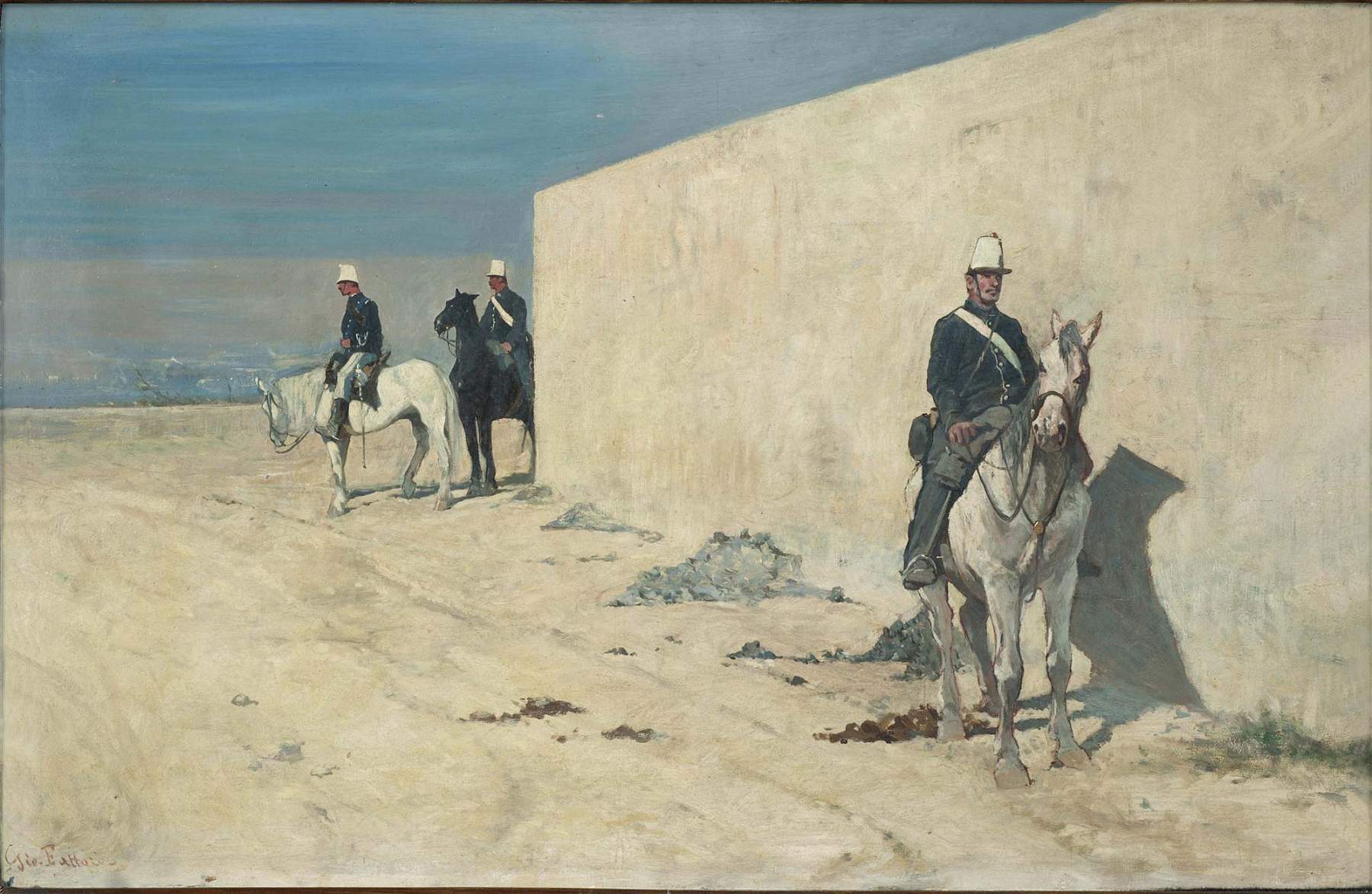

With the 1870s, the group activity of the Macchiaioli declined. The disappearances of Sernesi and Abbati, the move to Paris of De Tivoli, Boldini, De Nittis, Zandomeneghi, and D’Ancona caused a slackening in the movement’s hold; it was enriched, however, by new recruits, the second-generation Macchiaioli, sensitive to the demands of international Naturalism. Some of them, from pupils sometimes also became patrons and protectors of the old masters. The last section deals with the start towards the twentieth century. A number of Lega’s paintings will be exhibited here, including La Lezione and A Mother, characterized by a rare stylistic perfection and an extraordinary inventive force. And finally, works by Telemaco Signorini returning from long journeys, and Fattori, who from disillusionment with the waning of the Risorgimento values that had marked the existence of his generation, moves on to desolation in Pro patria mori, conceived in the aftermath of the Italian defeat at Dogali. Risorgimento values are now forgotten, like that soldier who died and was abandoned in the wasteland of a foreign land.

The exhibition opens Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m., Saturdays, Sundays and holidays from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. The ticket office closes one hour before. Reservations recommended but not required. Tickets: full 12 euros, reduced 10 euros (groups, over 65s, 18-25 year olds, concessions), reduced university 5 euros (University of Pisa and Scuola Normale Superiore students, valid on Thursdays only), reduced youth 6 euros (6 to 17 years old), reduced schools 5 euros, free for children under 6 and disabled. For information visit the Palazzo Blu website.

|

| Pisa, at Palazzo Blu a major exhibition dedicated to the Macchiaioli painters |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.