Scheduled at the Museo Civico delle Cappuccine in Bagnacavallo, Ravenna, from September 15, 2018 to January 13, 2019, is the exhibition Max Klinger. Unconscious, Myth and Passions at the Origins of Human Destiny, entirely dedicated to the graphic production of Max Klinger (Leipzig, 1857 - Großjena, 1920), an important German master of Symbolism: the exhibition comes after the success of the exhibition Goya. Madness and Reason at the Dawn of Modernity, which was dedicated to Francisco Goya (of whom Klinger was a great admirer) and, like the current one, focused on graphic art: in fact, the Capuchin Museum’s goal is to give life to a broad project aimed at popularizing the great masters of graphic art.

The work of Max Klinger represents a fundamental chapter in European art between the 19th and 20th centuries and in the history of 20th-century printmaking. For too long forgotten, and then rediscovered thanks to the major 1950 retrospective held in Leipzig, Klinger’s art is living testimony to how art becomes the interpreter and witness of its own time. Klinger, a versatile artist (he was a painter, sculptor, printmaker, musician, theorist, and skilled draughtsman), experimented with the possibilities of “black and white” with absolute mastery: already at the age of twenty-six he produced of six cycles of etchings and set about writing a theoretical text comparing different art forms, Malerei und Zeichnung (“Painting and Drawing,” published in 1891), which remains essential reading for understanding how much the “stylus arts,” as he called printmaking and drawing, underpinned his research and exerted a considerable influence on the generations to follow. From the earliest cycles, Klinger was already affirming his desire to be a peintre-graveur far removed from the tradition of the landscape or portrait painters then in vogue; what fascinated him was classicism, the myth that he found in the work of Arnold Böcklin (Basel, 1827 - Fiesole, 1901). His is an exercise in style and at the same time an unaggressive, almost conservative symbolism, claiming realistic iconographies but interpreted in the light of the symbol, a symbol heir to the Romanticism that reigned in the 1820s and which Böcklin knew how to twist and innovate well. Klinger straddles inner worlds and reality, in a dialogue between an inside and an outside that is the motif of his creative genius. His scenes then appear as realities contaminated by dreams, borrowed from the unconscious, modulated according to the quest for perfection. The art of the sign has “more extensive possibilities for the representation” of states of mind, whether they are also horrific or charged with anguish. Like Goya, Klinger works by series: he writes that “a single series of black-and-white images summarizes as many experiences as life itself offers, and in rapid succession. Epic breadth, dramatic concentration, ironic dryness, all possibilities of expression are granted to the images, for they are nothing more than fleeting shadows.”

Nearly 150 graphic works from prestigious collections are on display in the exhibition: From the earliest plates of the Radierte Skizzen(Opus I, Etching Sketches) to Eve and the Future(Opus III, 1880), as well as Intermezzi(Opus IV, 1881), Amore e Psiche(Opus V, 1880), Un guanto(Opus VI, 1881), Una vita (Opus VIII, I884), Dramas(Opus IX, 1883), A Love(Opus X, 1887), Fantasia on Brahms(Opus XII, 1886), Death, Part Two(Opus XIII, 1898-1910), up to the artist’s last published cycle, The Tent(Opus XIV, 1915). Also presented in the exhibition are a number of loose sheets such as the mysterious Isle of the Dead (1898), taken from Böcklin’s painting of the same name, suspended in silence, the plates still inferred from the Swiss artist’s Spring (or The Three Ages of Man) and The Fountain, as well as the Self-Portrait of 1915, the Nude of a Woman executed in mezzotint and the cover of Secession of 1893.

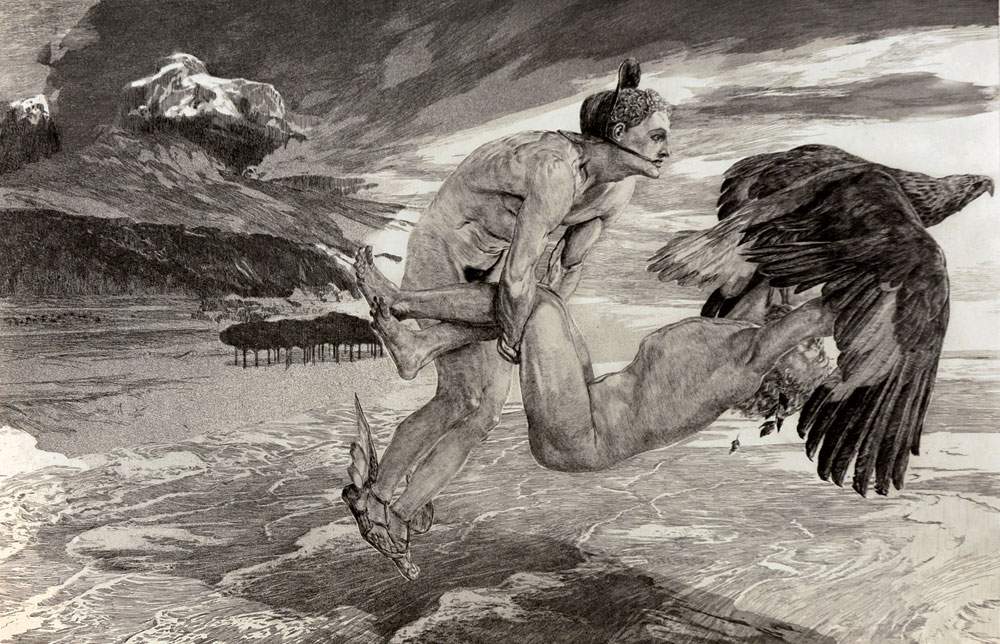

Writing about Klinger in 1920 and his Transport of Prometheus, chosen as the exhibition’s symbolic image, Giorgio De Chirico (Volos, 1888 - Rome, 1978), who owed much to the work of the German Symbolist genius, said, “Nothing in this work is cloudy and mistyly fantastic, the viewer participates in the emotion of that strange flight...in the relative he makes the impression of a scene that really happened.” For the artist father of metaphysics, Klinger represented “the modern artist par excellence, modern in the sense of a conscious man who feels the legacy of centuries and centuries of art and thought, who sees clearly in the past, in the present and in himself.”

Max Klinger. Unconscious, Myth and Passions at the Origins of Man’s Destiny is open Tuesdays and Wednesdays from 3 to 6 p.m., Thursdays from 10 a.m. to noon and 3 to 6 p.m., Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from 10 a.m. to noon and 3 to 7 p.m. Closed Mondays and post-holidays, special evening openings (until 11:30 p.m.) Sept. 27-30. Free admission. For info and guided tours for groups call 0545-280911, email centroculturale@comune.bagnacavallo.ra.it or visit the Bagnacavallo Capuchin Museum website.

Pictured: Max Klinger, The Abduction of Prometheus (1894).

|

| Max Klinger's unconscious, myth, and passions in an exhibition devoted to etchings by the great German master |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.