In Urbino, a major exhibition celebrates the 600th anniversary of Federico da Montefeltro's birth

Urbino celebrates the six-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Federico da Montefeltro (Gubbio, 1422 - Ferrara, 1482) with an exhibition entitled Federico da Montefeltro and Francesco di Giorgio: Urbino at the Crossroads of the Arts, scheduled from June 23 to October 9, 2022 at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, curated by Alessandro Angelini, Gabriele Fattorini and Giovanni Russo. An itinerary of eighty works, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, medals, detached frescoes and codices, a third of which come from abroad, to take the public on a journey through the duchy of Urbino at the time of Federico da Montefeltro’s patronage, a period of considerable importance also for the developments of Italian art at the time.

In addition, also from June 23 to October 9 at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, another exhibition joins the main one: it is "Quando vedranno i rich vistimenti. Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza. Clothes and Power in the Early Italian Renaissance, curated by Carolina Sacchetti’s “Atelier di Battista” of Urbino and organized by the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, an exhibition that repurposes a historical reconstruction of six Renaissance outfits from Federico da Montefeltro’s time.

“Duke Federico,” explains Luigi Gallo, director of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, “was able to transform Urbino into a capital of the Renaissance: at his court, artists and men of letters of different backgrounds and origins met, whose mutual influences generated a cultural climate that would reverberate in the decades to come. That milieu, which saw painters such as Piero della Francesca, Giusto di Gand, Pedro Beruguete and Luca Signorelli, architects Luciano Laurana, Francesco di Giorgio Martini and Donato Bramante meet, was the humus from which Raphael’s genius flourished and on which, Baldasar Castiglione, shaped the Cortegiano.”

The sections of the exhibition

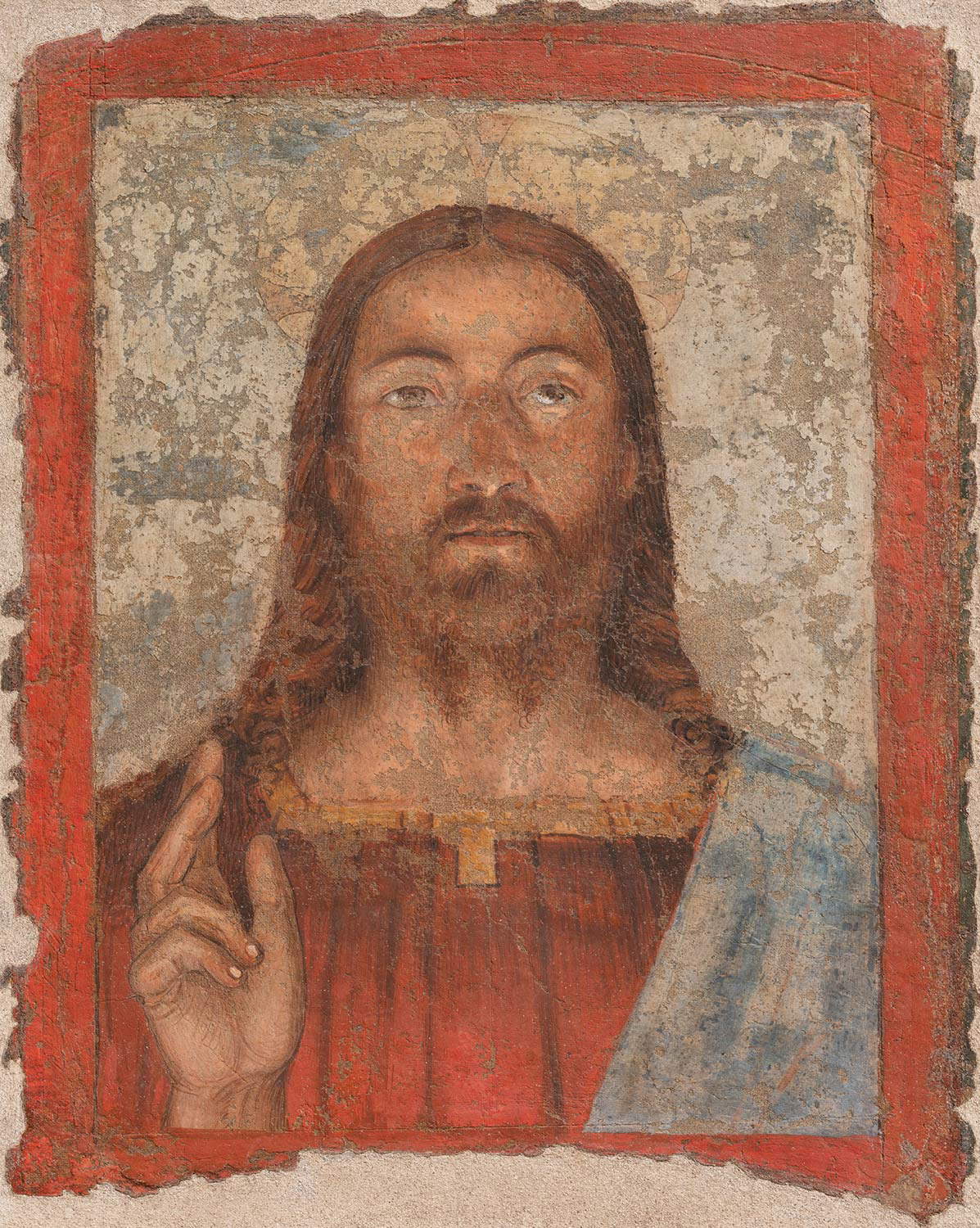

There are seven sections into which the exhibition is divided. The first, entitled Return of Federico da Montefeltro to Urbino. Piero and the Prospective Antecedents (1462-1476), takes its starting point from the 1470s, a time when the great artist Francesco di Giorgio Martini was appointed “architect” to the duke, with functions including overseeing the structural and decorative works for the factory of the Ducal Palace, as well as those of the predominantly military construction sites scattered throughout the Feltresque territory. These were the years during which, partly due to Federico da Montefeltro’s more constant presence at the palace, Urbino became more and more of a crossroads of the arts, with a vocation for cosmopolitanism hardly detectable in other Italian courts of the time. Characterizing this initial part of the exhibition is the bust of Battista Sforza, by Francesco Laurana from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, accompanied by the Flagellation belonging to the period when Piero worked for the Adriatic courts.

The second section, Francesco di Giorgio da Siena a Urbino, delves into the early stages of the work of the Sienese artist, who is attested with certainty at the Feltre court from at least 1477. The section contemplates a number of works, both paintings and sculptures, that recall the activity of his last years in Siena, such as the bronze gisant for the sepulchral monument of the great Sienese humanist Mariano Sozzini, originally in the church of San Domenico in Siena and now preserved at the Bargello. The presence of the Madonna and Child and an Angel from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena evokes the activity in Francesco di Giorgio’s workshop of one of his faithful collaborators, hitherto unidentified anagraphically, the so-called “Fiduciario di Francesco,” who probably followed the master closely in Urbino as well. The third section, Francesco di Giorgio bronzista e plasticatore, collects the bronzes executed by Francesco at the time of his Urbino activity, together with some significant works as a plasticatore, useful in revealing the Sienese master’s great familiarity with sculpture “per via di porre.” The key work is, of course, the Deposition from the Church of the Carmine in Venice, which comes from the Oratory of the Cross in Urbino and against the background of which Francesco di Giorgio portrayed Federico da Montefeltro with his very young son Guidubaldo, around 1475. Then exhibited are the two stucco versions of the Discordia, a relief in which Francesco di Giorgio reveals his great skill in perspective and deep debt to Donatello’s culture, to arrive at the large three-dimensional, polychrome fictile group depicting the Lamentation and the related sketch, which by then marks the master’s return to Siena in the mid-1980s.

It continues with the fourth section, entitled Court Painting in the Shadow of Piero della Francesca, which offers some of the most significant works from the years when Piero della Francesca was active at court: among them the Madonna of Senigallia, which in their architectural backgrounds, so measured and rational, seem to be inspired by the very interiors of the Urbino palace. Alongside will see their presence paintings by a direct pupil of the great borghigiano, such as the young Cortona-born Luca Signorelli, to whom we also owe a panel with the Portrait of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro as a child, preserved today at the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. The section entitled Perspective Culture and Flemish Light, on the other hand, highlights that in painting the Urbino environment of those years was characterized by extraordinary experimentation, as a center of avant-garde in Italy. Its admirable cosmopolitanism, to which Giovanni Santi’s Cronaca rimata bears first-hand literary witness, sees the presence of supreme Italian artists, such as Piero della Francesca, and masters of Flemish culture, such as Giusto of Ghent, or the Castilian Pedro Berruguete, who in his portraits shows an admirable synthesis of highly complex perspective solutions and epidermal values as a great Ponentine painter, for a culture that went back to the illustrious founders of Nordic painting.

Finally, the sixth and seventh sections of the exhibition are devoted respectively to Francesco di Giorgio, the duke’s "favorite architect," with the purpose of illustrating the taste for a rational and old-fashioned architecture that emerged at court in the presence of the Sienese master, and to The Palace Building Site and Old-Fashioned Ornamentation, a sort of itinerary inside the palace, to explore the building site of the “city in the form of a palace,” marked by an architectural style and old-fashioned ornamentation of strict Albertian taste. In reality Leon Battista Alberti, attested in Urbino in 1464 only in passing, may have offered only ideas and cues for a layout that was elaborated instead by Luciano Laurana during the 1960s and 1970s, and then specifically by Francesco di Giorgio, as far as the final solution and final arrangement of the architecture with its precious decorations is concerned.

The exhibition is enriched by the catalog published by Marsilio, which, in addition to photos and worksheets, will bear texts by the three curators, Director of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche Luigi Gallo and other essays.

The exhibition on historical clothing

“When they see the rich vistimenti”. Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza. Clothes and Power in the Early Italian Renaissance is a small exhibition showcasing the reconstruction of six historical dresses from the 15th century: two will recall the outfits from Piero della Francesca’s Urbino Diptych, the famous double portrait housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence; the other four (two female and two male) will be faithful remakes of clothes of the period, the result of an in-depth study of historical sources, since nothing has unfortunately come down to us of the original clothes of the time. The exhibition will be set up in the first room of the Guest Apartment of the Duke’s Palace, where the Flagellation and the Madonna of Senigallia are on display.

From the late Middle Ages clothing and ornaments began to take on considerable social importance: a large part of the craft production of the time was devoted to the making of cloth, jewelry, robes and accessories essential for emphasizing the social status of individuals. The dowry lists of noble maidens were almost entirely composed of robes and jewelry, as were the inventories of the estates of great lords, in which there are constant listings of sumptuous gowns and jewelry for every occasion, precious items that were often offered as gifts at weddings and engagements, important visits or simply to flaunt unbridled luxury.

It was in the refined Italian courts of the 15th century that both the modern concept of elegance, that is, standing out through the juxtaposition of different fabrics, colors and fashions, began to spread, as well as the development of social attitudes that pitted the aristocratic class, which made dress a self-celebratory mirror, against the wealthy merchant bourgeoisie, which also saw clothing as a patrimonial asset. Italian courts, centers of cultural diffusion on par with the court of Burgundy, became promoters of refined elegance. It is precisely in this context that the refinement of the Urbino court should be placed, which under the rule of Frederick and Battista, influenced by Flemish fashion, reached one of its greatest moments of splendor. Images of the dukes tell of power primarily through the fashions and colors of their robes.

Against such a backdrop, reconstructing some of the precious clothing apparatus of the lords of Urbino became a necessity, according to the exhibition organizers, since nothing has been preserved of the “fashion objects” of their time. Through the handcrafted reconstructions of the robes, made with a thorough historical study of the available sources and artifacts, the idea of elegance of the Feltresque court was sought to be restored.

Practical information

The exhibition opens Tuesday through Sunday from 8:30 a.m. to 7:15 p.m. (ticket office closes at 6:15 p.m.). Admission: € 8 full; € 2 reduced; € 1 reservation. For information phone 0722 2760, website www.gallerianazionalemarche.it.

|

| In Urbino, a major exhibition celebrates the 600th anniversary of Federico da Montefeltro's birth |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.