A history more than 130 years long, intertwined withItaly’s path of growth, with the changing tastes, styles and rituals of society, and always deeply linked to the city of origin: to that Central European culture, that crossroads of peoples, religions and knowledge that Trieste, the city of coffee par excellence, still represents today.

Hausbrandt and Trieste. Mitteleuropean Culture and Trade 1892 - 2023 is the event/kermesse promoted by the Hausbrandt Foundation, with the co-organization of the Municipality of Trieste, the Patronage of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region and the city of Treviso, which from September 9 to October 22, 2023 will enliven the Salone degli Incanti, in the city of Trieste, with the intention of reconstructing the long, extraordinary journey of the famous coffee brand present in 90 countries around the world.

The event, strongly desired by the City of Trieste and welcomed by Martino Zanetti, President of the Hausbrandt Foundation, aims to enhance and celebrate the close relationship between the city and the company. The importance of the event is also underscored by the presence at the vernissage assured by the Presidents of the Central European Industrial Associations. RepresentingAustria will be Markus D’Asburgo, a fraternal friend of Martino Zanetti’s family. Their participation assumes great relevance as Hausbrandt Trieste 1892, doyenne of European industry, wanted to dedicate this exhibition and the effort to organize it to the city of Trieste but also to the growing sharing by Central European industrialists of the will for peace, the only context in which civilization can flourish.

Hausbrandt

HausbrandtThe curatorship of the event Hausbrandt and Trieste. Central European Culture and Trade 1892 - 2023, which will feature talks and concerts, has been entrusted to architect Luciano Setten. A brand that has become, since that distant 1892, a family icon recognized in the collective imagination, thanks also to the graphic choices, the corporate image created by great artists of the 20th century and some communicative solutions, at times revolutionary, with which Hausbrandt has been able to innovate, in the crucial flow of the so-called short century and still today, marketing and advertising.

Great personalities, such as that of painter and poster designer Leopoldo Metlicovitz, advertisers Luciano Biban and Robilant and the Demner Merlicek & Bergmann firm, will be among the protagonists of this tale, which, in the process, will also give an account of the Trieste of the time and make evident the passing of fashions. In the city that made the history of coffee and cafes, as charismatic places throbbing with cultural connections, here, then, is an intense journey-through historical images, design and industrial objects, sketches, graphics, logos, and archival materials-to discover the nodes of the image success of this ultracentenary brand, representative of one of Italy’s excellences: an image preserved and enhanced even in the company’s recent course by Martino Zanetti.

In his dual role as president of the Hausbrandt Group and as an artist, and a devotee of the Arts, Music and Letters, Zanetti has contributed in recent years to innovating communication, starting precisely from one of his works, Figure 1, to flood iconic instruments and merchandising of thecompany; on the occasion of its 130th anniversary, he also gave a new look to the world-famous Moka Hausbrandt, the humanized cùccuma that drinks a cup of its own coffee, created in the 1960s by the famous Friulian artist Luciano Biban: an intervention that recalls the firm connection with the iconography of early 20th-century advertising and Hausbrandt’s Central European soul.

Alongside The Story of the Brand, which opens by recalling the first slogan chosen, at the end of the 19th century, to highlight in a simple and direct way the quality of this coffee - Specialty Coffee Hausbrandt, a motto so innovative and immediate that it soon became synonymous with the Company itself - the journey through the beautiful spaces of what was once Trieste’s Central Fish Market (built in 1913) is completed with a section devoted to La Tecnica, including coffee sacks, grinders and coffee machines for coffee bars from the 1950s onward, and a tribute to Il Territorio, or Trieste of yesterday and today.

Hausbrandt, after all, has always been attentive to technological innovation in coffee preservation and processing: it was the first company to offer products processed and packaged in metal containers, sealed inside the factory, and as early as 1900 it had presented the patented Grevenbroich system:an innovative system with an electric motor and cooling mechanisms that guaranteed perfect coffee roasting and aroma. Thus, too, the evolution of coffee machines, from the manually operated lever-type machines of the 1950s to the sophisticated ones of today, testifies to the coffee industry’s growing focus on quality.

So Trieste. The connection with the city of Svevo and Saba is fundamental to the company’s history. When Hausbrandt’s adventure begins, the city is an important trading hub for coffee, a hub of relations between Central European countries.

Coffee culture had long since expanded like wildfire in Italy and Europe. In Venice, the first public café had been opened in 1643, about a century after the first coffee bean used by doctors and apothecaries apparently arrived in the Doge’s city; it was followed by France, where the drink was also introduced at the court of Louis XIV, and especially byAustria, which-with the first café opened in Vienna in 1683, following the invasion of Ottoman troops-would play a key role in the birth of Hausbrandt in Trieste. Indeed, it was under theHabsburg Empire that the city, named a free port by Charles VI of Austria, became a crucial hub of the Empire’s trade, and the import of coffee became one of the major occupations of the Trieste port, now the Mediterranean ’s main port of call in the sector.

In 1748, the first coffee house opened in Trieste: many others would follow between the 19th and early 20th centuries, still bearing witness in their furnishings, architecture and atmosphere, to the fashions and styles of different historical periods. But it was above all their destiny as a meeting place for artists, philosophers, politicians and intellectuals that made the cafés the fervent and vital heart of debates and crucial changes in society, where, in the meantime, one could sip what theenlightened Pietro Verri in 1764 called-in the pages of the philosophical-literary journal "Il Caffè,“ founded with his brother Alessandro and Cesare Beccaria-a drink ”that enlightens the spirit and comforts the soul."

A year before Hausbrandt was born, the Industrial Association was formed in Trieste, and in the early 20th century the Stock Exchange was opened.

Today, the link between Hausbrandt and Trieste is also demonstrated by the commitment of the Hausbrandt Foundation, which-born at the behest of Martino Zanetti in Austria-as well as addressing studies and research related to the Renaissance age, intends to contribute to the debate on the enhancement of the city’s historical architectural heritage, as recalled by the meta-project for the recovery of the historic Palazzo Carciotti, illustrated in the exhibition.

Just as the exhibition ends on Oct. 22, a gala event related to fundraising for projects that the Hausbrandt Foundation will dedicate to Palazzo Carciotti is planned.

Hausbrandt from its inception understood the importance of defining its image and the need for communication or, rather, careful “propaganda” as it was called at the time.

The advertising image of the product in the early days of modern entrepreneurship is not an issue immediately addressed except by very few forerunners, and between the latenineteenth century and up to the 1930s the distinction between artist, illustrator and publicist is practically absent, free as the creative people were from marketing needs and rules.

Already in the Bell’Epoque years, Hausbrandt had used innovative advertisements and precursor graphic solutions, such as the drawing of the Turk sipping coffee and raising three fingers to emphasize three words, “Hausbrandt Coffee Specialty,” an example of very modern formal synthesis, symmetry, and at the same time great iconicity in the orange turban; or like the famous 1910 campaign - diametrically opposite in character but no less effective - with the so-called “Old Men,” indebted to the romantic realism inspired by the American Norman Rockwell and still one of the company’s most recognizable graphic signs.

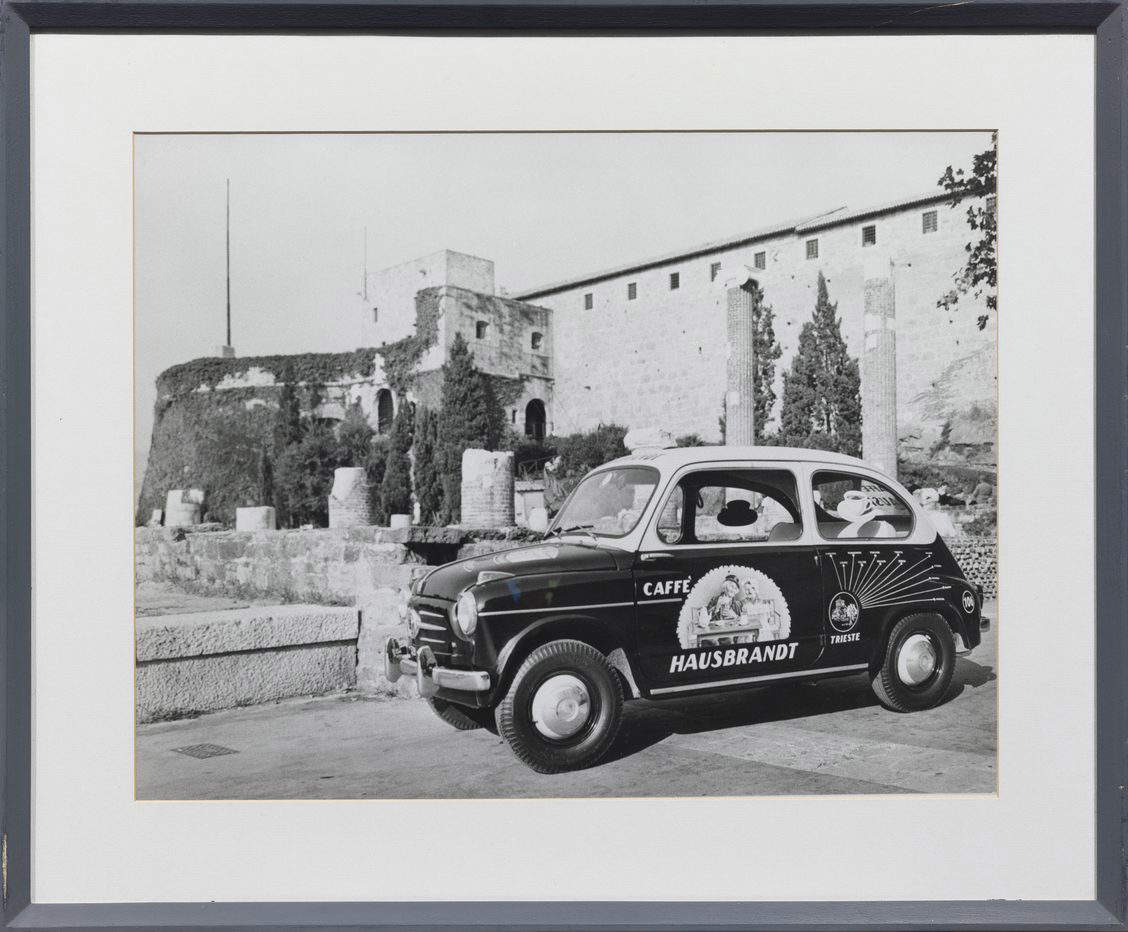

Likewise, the slogan used is included in the packaging and on the company’s first vehicles, implementing a coordinated declination of the promotional campaign that was still unknown for the time.

It would be in the years immediately following, however, that the first Italian roasting industry began to collaborate with some of the most important artists also engaged in advertising graphics, including the Triestine Metlicovitz considered among the fathers of modern Italian poster art.

Leopoldo Metlicovitz, in particular, a painter and illustrator born in Trieste in 1868, had become famous by working with the Casa editrice musicale and Officine Grafiche Ricordi-his posters for Tosca, Madama Butterfly and Puccini ’s Turandot-but also as a set and costume designer for La Scala Theater, an illustrator of librettos, sheet music, calendars and magazines.

Before devoting himself almost exclusively to painting, as an illustrator on the works had also appeared in La Lettura (1906-1907,1909) monthly of the Corriere della Sera, and in 1906, on the occasion of the great Universal Exhibition in Milan, Metlicovitz had won the competition for the poster symbol of the fair, dedicated to the Simplon Tunnel. So among his various assignments, his engagements in cinematography, particularly for Italia Film, stand out.

On display, therefore, will be some of the first Hausbrandt advertisements designed by the Triestine genius, but also and above all the original sketches for the creation of a backdrop and a sign for Casa Hausbrandt in Trieste, with also the scenographic reconstruction of this long backdrop, based on the indications left by the artist himself to accompany the sketches.

Indeed, by placing side by side the lithographic reproductions of each drawing, depicting a different stylized character in which a letter of the alphabet is distinguishable, the Hausbrandt name is formed in a 6-meter-long arched wall: “Bringing the ten drawings closer together, touching each other,” Metlicovitz wrote, "one already enjoys the image of this arched barchessa, which will be in time the Hausbrandt House.

A scenic barchessa that was meant to serve as a backdrop at a sample fair in the 1920s, but was also destined to become a communicative element of the brand in the Hausbrandt Coffee drinking establishments.

And while there are many curiosities that show the exploration of new communicative possibilities and real expressive experiments-such as the six paintings proposed for a Maccò advertising campaign, some in the style of Depero and with a funny rhyming story, that were to be reproduced and printed front/back by De Agostini-another fundamental moment in the brand’s history, recalled in the exhibition, is the one related to the creation and multiple transformations of the Hausbrandt Moka the logo still a strong symbol of the company today.

It was Luciano Biban, Venetian by birth and Friulian by adoption, born in 1935 and deceased at the age of only 33, who in 1967, by participating in a competition, gave life to the “humanized coccuma” that will remain in the history of Italian communication and will become identifying with the pleasure of Hausbrandt quality coffee.

To complete the logo, Biban - devoted to advertising graphics, but also to painting, which had already earned him several prizes and awards - also inserted a payoff, placed there where the aroma of coffee is released, the first sensory characteristic of those who are about to drink it: “The pleasure of a good coffee,” Biban proposed, later modified to “What a pleasure...a good coffee.”

In 1980, it would be Robilant Associati who would evolve the iconic logo, anchoring the Moka to a rectangle that better defined it, making the sign more graphic and less pictorial, and inserting the colors-red and yellow-that have distinguished the Hausbrandt brand around the world; then, so 20 years later, in 2019 it was the Vienna-basedDemner, Merlicek & Bergmann Agency, founded in 1969, that undertook the restyling of the logo and product communication system.

The Moka becomes black and stylized, the look becomes more Central European, and the mood of the brand changes without distorting. The basic elements remain the oblique cut lettering and the Moka, with the essentiality of a pure and minimal style.

Finally, Martino Zanetti, who celebrated Hausbrandt’s 130th anniversary by personally intervening on the colorful, winking logo of its origins, in his revisitation of Roibilant. The animated ladybird, drinking steaming coffee, herself comes out of a stylized cup cheerfully exclaiming “What a coffee!” to express the concepts of conviviality, sharing and joy that are Hausbrandt’s values.

Pictured: Hausbrandt coffee shop, 1920s

|

| In Trieste, an exhibition traces the history of Hausbrandt Coffee. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.