In Seravezza a major anthological exhibition on Gianfranco Ferroni. Sgarbi: a painter who elevates everyday life through art

The Gianfranco Ferroni exhibition is being held at the Palazzo Mediceo in Seravezza. Before and After the ’68 Biennial. Everything is coming to fruition, from July 8 to September 16, 2018. The exhibition aims to retrace the career of Gianfranco Ferroni (Livorno, 1927 - Bergamo 2001), an artist who has experienced intense rediscovery and re-evaluation in recent years, with two exhibitions dedicated to him, one in 2007 in Milan (Palazzo Reale) and one in 2015 in Florence (Uffizi), as well as several publications. The Seravezza exhibition emphasizes the year 1968 not only as a watershed in Italian history, but also as a turning point in Ferroni’s artistic journey. The hundred works that make up the exhibition’s itinerary, chosen by curator Nadia Marchioni (assisted by a scientific committee chaired by Carlo Sisi and composed of Arialdo Ciribelli, Andrea Tenerini and Marco Vallora) aim to reconstruct the dense weave of Ferroni’s career, highlighting that turning point characterized by the disillusionment resulting from the “missed” revolution of 1968 and the refuge in a politically disengaged but, on the contrary, lyrical and almost mystical painting.

The exhibition consists of ten sections: it begins with the years when Gianfranco Ferroni frequented the artistic-literary milieu of the Bar Giamaica in Milan, near theBrera Academy. Years, as he had to say, of “loneliness, hunger, strikes, cinema, reading, jazz, games of bocce and pinball,” and of an “existentialist” conception of art. Then came the shock of the events in Hungary, his exit from the Communist Party, the disappearance of his mother to whom he was very close (only two years after that of his father), and the opening to new figurative horizons that led the artist to analyze reality with a new formal intention. The exhibition then moves from the politically themed works of the early 1960s to Ferroni’s subsequent social engagement: at the center of this journey is the special section devoted to the Biennial of ’68 (in which Ferroni participated by turning his works against the walls, in protest against police charges), with some of the Leghorn painter’s most significant works, such as the painting of denunciation Tutto sta per compiersi (Everything is about to happen), charged with aspirations that he would later define as “bitterly unfulfilled.” Also in this section are large-format photographic reproductions from theUgo Mulas Archive depicting protesters in Piazza San Marco during the days of the Biennale. Also: the creative crisis of the early 1970s and his retreat to Viareggio, where Ferroni shared a studio with Sandro Luporini, Giorgio Gaber’s historical collaborator; his return to painting in an increasingly intimate key, to “investigate the small, prosaic world” around him; the Metacosa experience; the works of recent years in which the investigation of reality, “which is reduced to pure luminous essence, is also pursued through refined photographic experimentation, arriving, in different media, at results of unprecedented suggestion presented together in the final section of the exhibition.”

“The exhibition,” Nadia Marchioni explained at the press conference, “is intended to be an anthology, starting in the 1950s and tracing the entire career of Ferroni, an artist who began his career in Milan in an environment, that of Brera in the mid of the 1950s, very much alive, which gave him the opportunity to meet those artists gathered under the label of existential realism, that is, an art that was neither linked to a political commitment nor followed the abstractionist research that was beginning to take hold. Ferroni’s commitment more than political at that time was social, because the artist was always sensitive to what was happening around him, and he suffered within himself what was happening in the world: his painting is participation in historical events. Ferroni was a very varied artist, and with the exhibition we wanted to represent this variety: he himself made a periodization of his painting career. In ’68, which Ferroni lived as an already mature man, with many hopes, participating and sympathizing with the demonstrations of those years, there was the episode of the Biennale, with the protest of the students charged in St. Mark’s Square by the police, and it resulted in a huge protest by the artists, who closed the Giardini preventing the opening of the event. The Biennale then reopened, and all the artists participated except Ferroni, Gastone Novelli and Carlo Mattioli: Novelli and Mattioli withdrew their works, while Ferroni kept his canvases turned against the wall for the duration of the event. It was a very striking gesture and also a testimony to how Ferroni had a very maximalist view of politics. From that same year Ferroni had a kind of disillusionment with this wave that could change something, he distanced himself from politics and also from the city, leaving Milan and moving to Versilia for four years. In these four years he painted very little, and when he started again he was a completely changed artist. His painting speaks of his everyday reality, it is a painting of absence, of lacks, of loneliness, it is his perception reality told as if he were living and seeing things for the first time, like an extraterrestrial. Ferroni wants to capture a kind of mystery that he intuits in things and in life. And he is one of the contemporary artists who make us think most about our existence in the world. The exhibition concludes with unpublished photographs, never exhibited before, which are meant to highlight another aspect of his artistic research: he photographed not only functionally for paintings to be painted but also to make photographs that had experimental quality and value.”

“The one in Seravezza,” emphasized Vittorio Sgarbi, who edited the introduction to the catalog and holds Ferroni’s work in high esteem, “is a path that is represented for the first time so precisely in an exhibition. The works that we see at the end, the most intense ones, envisage a divinity that is foreign to the historical Ferroni: Ferroni becomes an atheist not only with respect to God, but also with respect to ideology (one who strongly believes in a party is not an atheist, because he has an ultimate idea of his life for which to sacrifice himself). In him, there is another God: the idea of an absolute within us. In his case, there is the idea of raising everyday life through art. In Ferroni there is no religious iconography or Christian iconography, but there is an idea that there is a high spirit within him that distinguishes him from other artists, so his is an ascetic path, which leads him to a mystical tension. It is a very intense and authentic painting: we go from painting against man, suffering painting, to painting that, aware that the individual cannot change the world, looks within itself. And the exhibition well accompanies these steps of a very curious and very complex personality. In seeing Ferroni’s work it seemed to me that the moment when he manifests an ideological adherence to the revolution of ’68 and to pop art is a moment when such an intelligent and sensitive man seems to get caught up in the wave of the masses (I don’t say by fashion, but by the idea of speaking a language that others also speak: something that neither Morandi nor he after the 1970s suggest: the beauty of their painting consists in being against history, against their moment). And so here he comes to ’68 and he makes this Duchamp-like gesture, which is to turn the canvases upside down, and he has the opportunity to do it in an exhibition where there is a narrative of himself. To have exhibited the paintings in this way was a good idea, because the paintings are real when he experiences such a strong human drama, when he understands that all painting, including his own, is decoration and is therefore not suitable for a moment of conflict.”

The exhibition is open Monday through Friday from 5 to 11 p.m. Saturdays, Sundays and holidays from 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 5 p.m. to 11 p.m. (ticket office closes half an hour earlier). Tickets: full 7 euros, reduced 5, family ticket (two adults with children up to 14 years old) 14 euros. Guided tour: every Wednesday from 7 to 8 p.m. and every Friday from 10:30 to 11:30 a.m. (cost: 10 euros admission and guide). Child-friendly visit: every Tuesday from 7 to 8 pm (cost: 6 euros). Let’s have fun learning LAB: every Monday from 17:30 to 19:00 and every Thursday from 21:30 to 23:00 (cost: 6 euros). Tours and educational activities are all by reservation required (phone: 339 8806229, 349 1803349). The catalog published by Bandecchi&Vivaldi (graphics by Enrico Costalli), with an introduction by Vittorio Sgarbi, includes contributions by Nadia Marchioni, Giacomo Giossi, Marco Vallora and Andrea Zucchinali.

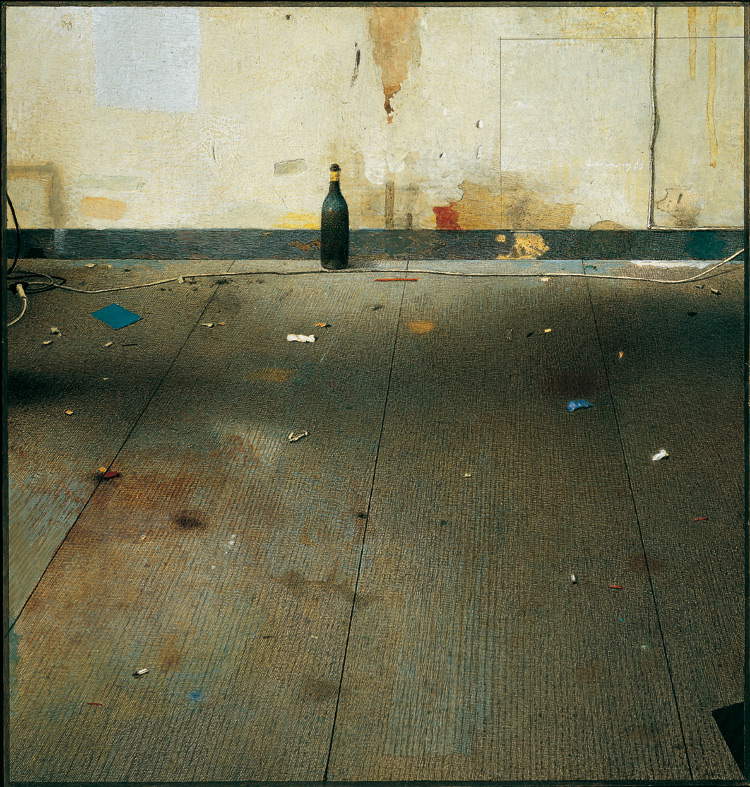

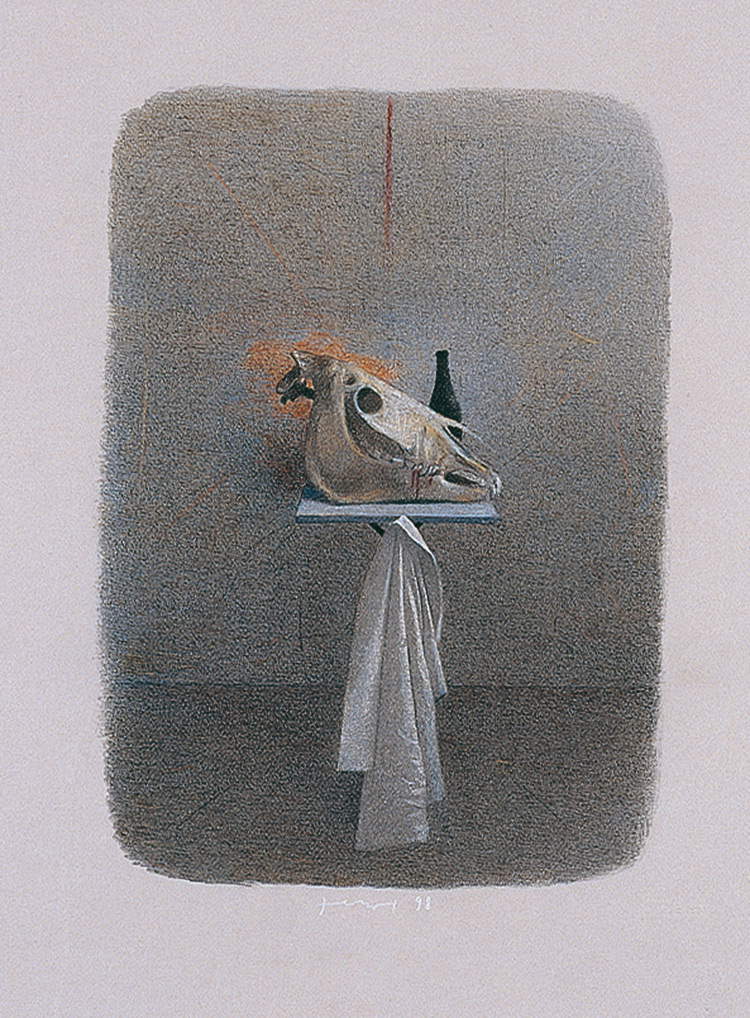

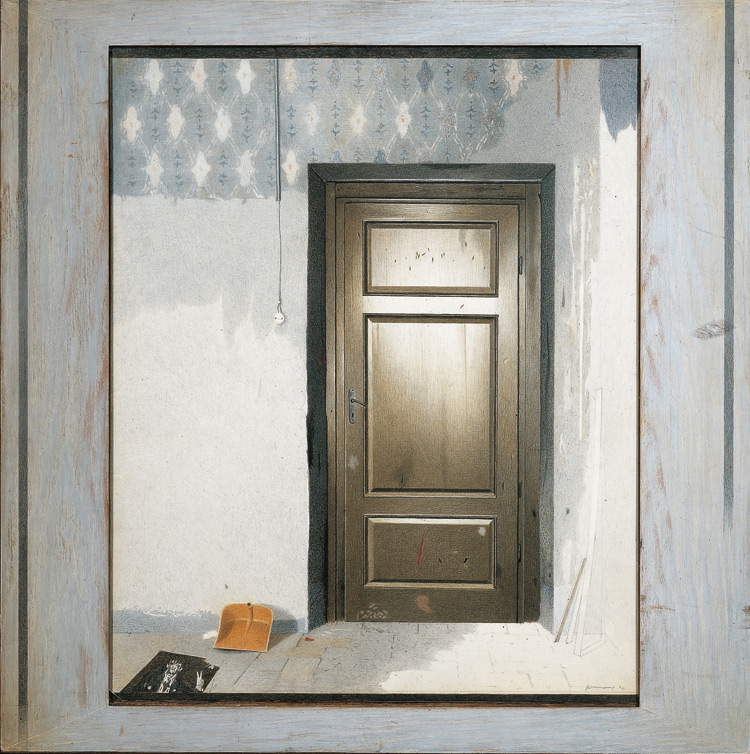

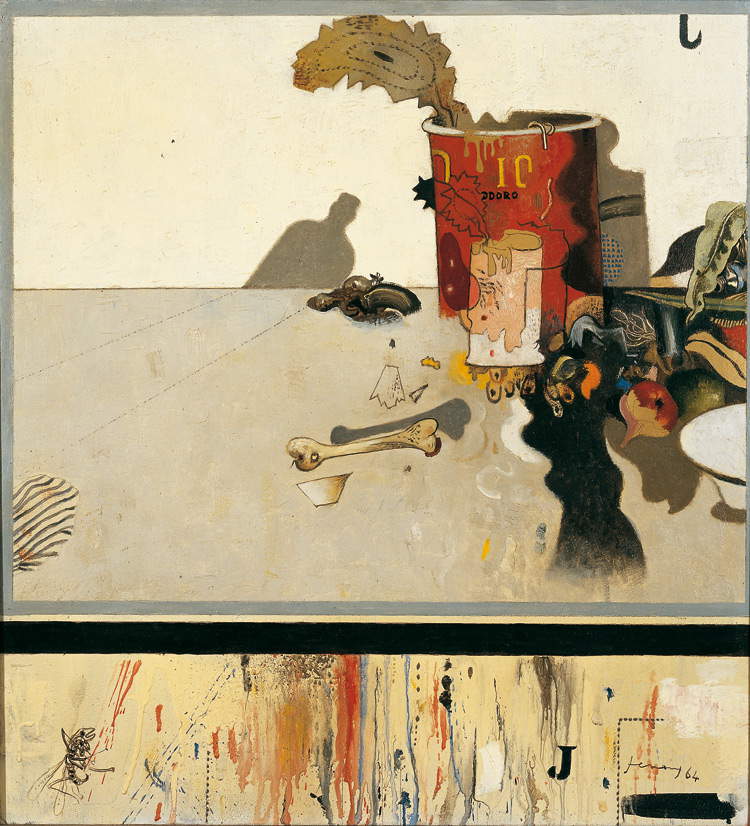

Below is a selection of images of works in the exhibition.

|

| Gianfranco Ferroni, Analysis of a Floor - Milan (1983, oil on panel; 43.5x41.5 cm; private collection) |

|

| Gianfranco Ferroni, City (1961; oil on canvas; 50x59.5 cm; private collection) |

|

| Gianfranco Ferroni, Equine Skull and Bottle (1998; mixed media on paper applied to panel, 61x50 cm; private collection) |

|

| Gianfranco Ferroni, Closed Door (1974; mixed media on paper applied to canvas, 83.5x83 cm; private collection) |

|

| Gianfranco Ferroni, Refuse (1964; oil on canvas, 52x47 cm; private collection) |

|

| In Seravezza a major anthological exhibition on Gianfranco Ferroni. Sgarbi: a painter who elevates everyday life through art |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.