by Redazione , published on 10/06/2021

Categories: Exhibitions

/ Disclaimer

From June 13 to October 3, 2021, the Museo del Paesaggio in Verbania is hosting the exhibition "Carrà and Martini. Myth, Vision and Invention. Lopera grafica," dedicated to the two great artists of the 20th century.

From June 13 to October 3, 2021, the Museo del Paesaggio in Verbania is dedicating an exhibition devoted to the graphic art of two 20th century greats, namely Carlo Carrà (Quargnento, 1881 - Milan, 1966) and Arturo Martini (Treviso, 1889 - Milan, 1947). Entitled Carrà and Martini. Myth, Vision and Invention. Lopera grafica, the exhibition includes works from the collection of the Verbania museum and from a private collection in Milan, and is curated by Elena Pontiggia and Federica Rabai, artistic director and conservator of the museum. On display are more than 90 works, mostly graphic works, by the two great artists who distinguished and established themselves precisely through the invention of a new language in painting and sculpture. Completing the path dedicated to myth and vision is a series of sculptures by Arturo Martini, presented alongside sketches, drawings and engravings.

The main corpus of the exhibition is dedicated to thegraphic work of Carlo Carrà : about fifty etchings and color lithographs are on display, including all of the artist’s most important achievements. They range from the landscapes of the early 1920s, traced with an essential and stupefied drawing(Houses at Belgirate, 1922), to the House of Love (1922), to the visionary images created in 1944 for an edition of Rimbaud, in which Carrà , against the backdrop of the world war, depicts angels, demons, mythological creatures and realistic figures, signs of death but also of hope(Angel, 1944). From the very beginning, moreover, Carrà initiates thanks to l’allincisione a systematic rethinking of his painting, which leads him to reinterpret with etchings and lithographs his main masterpieces, from the Futurist Simultaneity to the Daughters of Loth, from the metaphysical Oval of Apparitions to the Mad Poet. Etching thus becomes for the artist a moment of verification, but also a kind of scrapbook of memories.

Carrà ’s first etchings (all etchings, with the sole exception of the lithograph I saltimbanchi, intended for a portfolio published in Weimar by the Bauhaus) date from 1922-1923. It was in 1924, however, that the artist systematically devoted himself to etching, thanks to the teachings of Giuseppe Guidi, who that year had opened an intaglio workshop in his own home at 16 Via Vivaio in Milan. In fact, he executed thirty-three etchings and printed the branches he had engraved, but not impressed, in the previous two years. Carrà adopts a synthetic, hard sign capable of expressing his world of figures and places removed from time. It is above all the landscape that attracts him, which he wants to transform into a poem full of space and dreams. From the very beginning, however, lincisione also serves Carrà to rework earlier works in an unconquerable quest for expression. This fervid initial season has anppendice in 1927-1928, when Carrà , who at that time adheres to the Selvaggio group (the Tuscan magazine animated by Maccari, to which Soffici, Rosai, Morandi and other artists are close) executes lithographs and etchings characterized by a more pictorial language.

In 1944, after an interval of sixteen years since his last etchings, Carrà returned to graphic art. Unlike the 1920s, when he had practiced mainly etching, it was now lithography that engaged him, both in black and white and in color. Carrà ’s plates are almost always grouped into articulated projects. In 1944 he published the portfolio Segreti (Secrets), in which a dreamy landscape (Lake Como, seen from Corenno Plinio where the artist was displaced in 1943) immersed in an unreal stillness comes to life. Also in this period he devoted himself intensely toillustration. In the same 1944 he executed twelve plates for Rimbaud’s Verses and Prose, where a world of angels, demons and signs of death appears (a reflection of the tragic moments of the war). In 1947 he illustrated Mallarmé’s LAprès-midi et le Monologue dun Faune, translated by Ungaretti. Starting in 1949, now in his seventies, he instead systematically reconsiders his own work. In the portfolio Carrà 1912-1921 (Venice 1950) and in the two albums Carrà No. 1 and No. 2 of the early 1960s, he takes up works from the Futurist, Primitivist and Metaphysical periods. The whole procession of muses and disturbing masks born forty to fifty years earlier come back to his memory with the levity of a daguerreotype, or with light and impalpable chromatics.

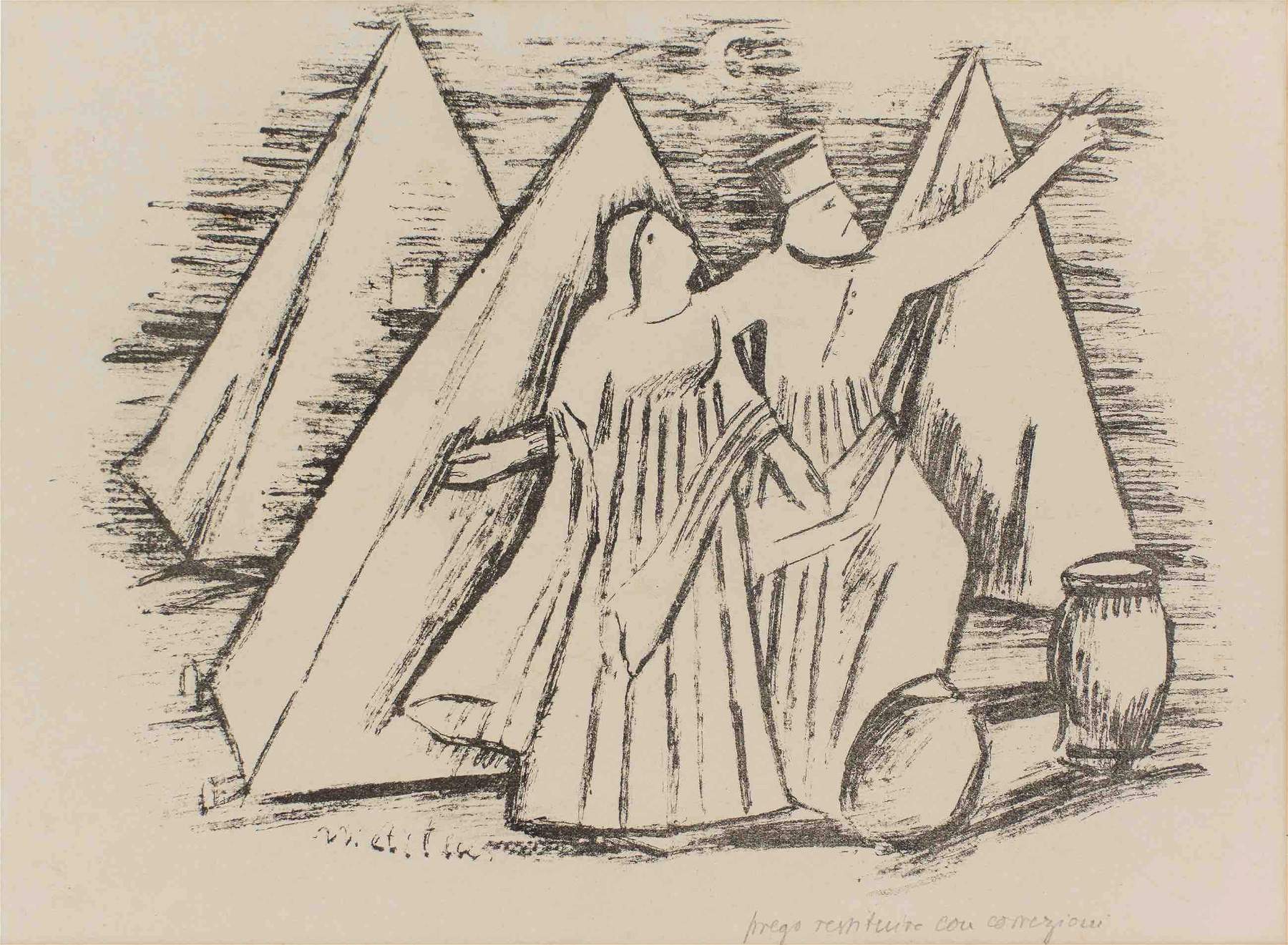

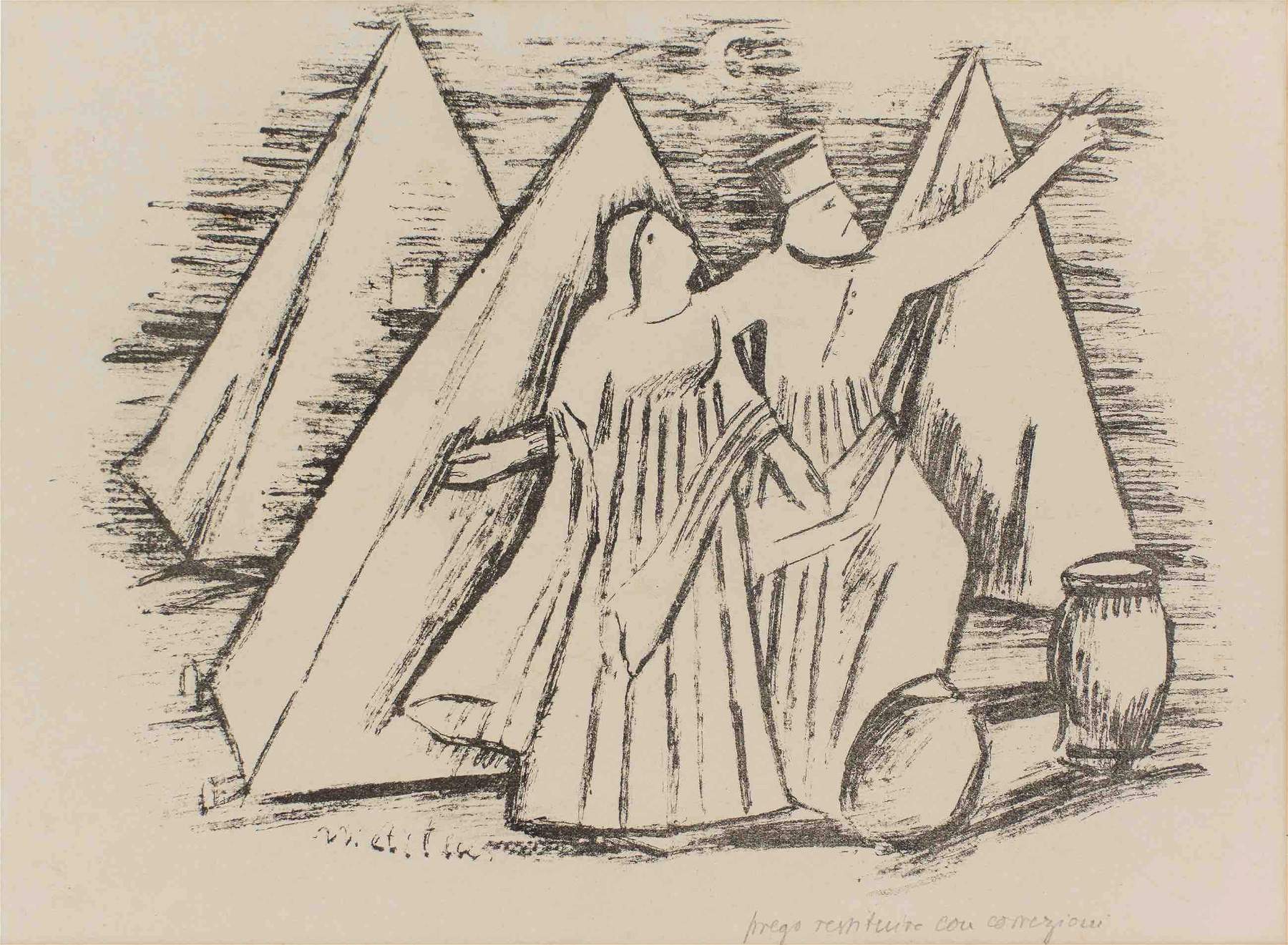

As for Arturo Martini, the exhibition features about forty works between 1921 and 1945, covering the artist’s entire career, beginning with the pencil-on-paper work Il circo of about 1921, an important drawing from the moment of Valori plastici when Martini was very close to Carrà and generally to a personal reinterpretation of the metaphysical conjuncture. It is reminiscent of Carrà ’s graphics for the bodies locked inside a sealing sign, and, at the same time, it seems to catch an echo of Picasso’s Parade, the grandiose curtain work executed in Rome in the spring of 1917 when Martini was also sporadically frequenting the capital. This is followed by Carnevale of 1924, an etching published in Galleria magazine accompanied by a short nonsensical poem on Carne-vale. It differs in lightness of stroke from the coeval woodcuts published in the same magazine, characterized instead by heavy, sculptural strokes.

Other works featured include the 1929 Lute Player, the first work given by Martini to Egle Rosmini at the time of their acquaintance, and still the only one with a dedication. It depicts a young man in a standing position, dressed in Renaissance clothing: strong assonances with a fresco, now partly lost, on a facade of a palace in Treviso, where the detail of the different dress in the two legs recurs. Also important is the cycle of engravings executed in Blevio in the summer of 1935 on subjects already treated also in sculpture (such as LAttesa and Ratto delle Sabine) or already present in other earlier engravings (such as Luragano; others, however, are new such as Il fabbro or Il Samaritano, which seems to participate even physically in the pain of the poor man’s vulnerable body. The fact that there are no stylistic similarities between the plastic works modeled in Blevio at the same juncture and these graphic works (a discrasia evident in the case of the bas-relief of the Rape of the Sabine Women in the exhibition) attests to the fact that Martini was accessing different means of expression precisely to detach one expressive register from the other. In these etchings the texture of the lines is dense to the point of obscuring the surface, almost emulating the black manner.

In 1942, Martini made 11 preparatory drawings, all featured in the exhibition, of Viaggio d’Europa for the illustration of Massimo Bontempelli’s homonymous short story. There is the same relationship between these preparatory drawings and the final version of the illustrations as there is between the sketches of the monumental works and the final result. Rigid and purely orientational, these sketches served Martini for an initial approach to the subject of Bontempelli’s tale, and while they testify to the presence of some of Martini’s topoi (the sleeper, the meeting of two figures, the spatial glimpses) and a general metaphysical climate, their provisional and studio character is evident. From 1944-45 are the group of etchings prepared by Martini for the illustration of the Italian translation of the Odyssey edited by Leone Traverso, later unpublished. Executed in Venice, they reveal an extraordinary side of Martini’s versatile imagination, again oriented toward experimenting with poor materials and poor languages, bordering between image and pure timbral suggestion. Published posthumously only in 1960, they are among the most convincing proofs of Martini’s graphic art. Alongside these proofs of the artist are exhibited ten sculptures such as The Family of Acrobats, Can Can, Adam and Eve, Ulysses and the Dog, Head of a Girl, Bust of a Girl, and three canvases(Samson and Delilah, The Siesta and Green Landscape), in order to reinforce the theme of the difference between drawing and the final realization of the works.

The exhibition is open Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tickets: full 5 euros, reduced 3 euros (the ticket entitles the visitor to visit the exhibition, the picture gallery and the Troubetzkoy gallery of plaster casts). For information: Tel +39 0323 557116, email segreteria@museodelpaesaggio.it, website www.museodelpaesaggio.it. Below is a selection of works in the exhibition.

|

| Carlo Carrà , The House of Love II or Interior or The Housewife (1924; etching on copper, 30.4 x 21.8 cm) |

|

| Carlo Carrà , Lovers (1927; etching on copper, 24.7 x 33.9 cm) |

|

| Carlo Carrà , Lovale delle apparizioni (1918-1952; six-color lithograph on zinc, 68 x 46.8 cm) |

|

| Carlo Carrà , Lamante dellingegnere (1921-1949; lithograph on zinc, 35.8 x 26 cm) |

|

| Carlo Carrà , La figlia dell Ovest o La fanciulla dellOvest (1919-1949; lithograph on zinc, 35.9 x 25.8 cm) |

|

| Arturo Martini, Lattesa (1935; pyrography on linoleum or celluloid, 17.5 x 15.3 cm on 35 x 25 cm paper) |

|

| Arturo Martini, Nausicaa at the Bath (1944-45; print on linoleum or plaster, 39.5 x 34 cm) |

|

| Arturo Martini, Ulysses and the Dog (1936-37; refractory clay, single specimen, 26 x 22 x 12 cm) |

|

| Arturo Martini, The Family of Acrobats (1936-37; original plaster, 38 x 21 x 34 cm) |

|

| Arturo Martini, La siesta (1946; oil on cardboard, 58 x 48.3 cm) |

|

| Arturo Martini, Viaggio dEuropa: Appears langelo Fenice (1942; lithographic pencil on paper, 28 x 37 cm( |

|

| Graphics by Carlo Carrà and Arturo Martini on display in Verbania with more than 90 works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.