From Neoclassicism to Romanticism: an exhibition on Pompeo Marchesi at the GAM in Milan

Milan remembers one of its greatest sculptors, Pompeo Marchesi (Saltrio, 1783 - Milan, 1858) with the exhibition Neoclassical and Romantic. Pompeo Marchesi, sculptor collector, scheduled from March 1 to June 18, 2023 at GAM - Galleria d’Arte Moderna. The exhibition, set up in the ground-floor rooms of the Villa Reale, is promoted by the City of Milan - Culture and is curated by Omar Cucciniello, curator of the Milan Gallery of Modern Art.

A great sculptor of the 19th century, a pupil of Canova, and a contemporary and friend of Francesco Hayez, Pompeo Marchesi represented the trait d’union in the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, in the lively environment of Milan between the Napoleonic Empire and the Restoration. The exhibition, 240 years after his birth, follows the bicentenary celebrations of Antonio Canova’s death and takes its cue from the latter’s precious plaster model of Hebe at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna to reconstruct the collection of the sculptor, an artist of fundamental importance to the history of the museum and the art collections of the City of Milan. Among the very rare models by Canova not to have flowed into the Possagno Gypsotheca, Ebe in fact arrived in the civic collections precisely as a result of Marchesi’s testamentary bequest.

The exhibition reconstructs the life and work of the sculptor, who trained at the Brera Academy under the auspices of Giuseppe Bossi and then in Rome under the direction of Canova. Marchesi’s figure is closely linked to the city of Milan, where in the Restoration years the artist achieved great success by participating in the city’s most important construction sites, from the Arco della Pace to the Duomo, and in artistic life as a professor at the Brera Academy. Known as the “Milanese Phidias,” he was defined by Stendhal, in his novel La Certosa di Parma, as “le sculpteur à la mode de Milan” (this is also the title of the first section of the exhibition), he had important commissions from all over Europe, from Vienna to Paris to St. Petersburg, evidence of a season of splendor for Lombard sculpture, known and sought after all over the world. Classicist and perfect in form, his sculpture is balanced between the search for an ideal and eternal beauty, borrowed from Canova, and the unfolding of a more modern Romantic sensibility, while the sketches show an unprecedented strength, very modern and almost anticlassical, that seems to translate Winckelmann’s advice to “conceive with fire but execute with calm.”

His grand atelier, rebuilt after a fire thanks to a citizen’s subscription and inaugurated by the Emperor of Austria Ferdinand I, was one of the city’s most fashionable places, remembered by Stendhal and Balzac, frequented by crowned heads, artists, writers, nobles and intellectuals, frescoed by Hayez and organized like a museum. It was here that Marchesi gathered all the plaster models and sketches of his sculptures, as well as the rich collection of artworks he had collected over the years. It was from this monumental place that his bequest originated: at his death the sculptor in fact destined all of the studio’s materials not to the existing art museums (the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Biblioteca Ambrosiana) but to the city of Milan, which at the time had no art collections. The first in a long series of gifts from artists and collectors that would follow in the following decades, Marchesi’s bequest thus stands at the origins of the civic art collections. The unexpected gift included the sculptor’s many works (models, sketches, drawings), but also everything he had collected during his lifetime: antique sculptures, drawings, engravings, paintings, cartoons and books, with particular reference to the artists who were his contemporaries, Andrea Appiani, Giuseppe Bossi, Francesco Hayez, Bertel Thorvaldsen and especially Antonio Canova, whose model of Hebe, perhaps the most precious work in the collection, he owned. The delicate grace of the cupbearer of the gods found a counterpart in the work of Andrea Appiani, whose splendid studies Marchesi possessed for the frescoes of San Celso, drawings for the grandiose cycle of Napoleonic Fasti, and also refined miniatures. Marchesi’s first contacts with Canova, during his years of artistic retirement in Rome, were mediated by Giuseppe Bossi, at the time secretary of the Academy and a great friend of the sculptor: of the latter Marchesi collected a series of drawings and cartoons, which testify to the variety and complexity of the Busto artist’s work, from studies of anatomy to ambitious compositions to studies on Leonardo da Vinci. Moreover, Bossi’s immense collection undoubtedly constituted an inspiration for Marchesi’s. Finally, Marchesi also pointed out among his models Bertel Thorvaldsen, known in Rome, emulated and opposed by Canova, whose bas-reliefs he owned, evidence of the consideration in which the Danish sculptor was held as the “patriarch of bas-relief.”

Despite losses due to historical events (the collection of cartoons was destroyed during the bombings of World War II), the Marchesi collection, in its variety and richness, is a valuable testimony to the taste of an entire era. Originally displayed unitarily in the first location of the Municipal Art Museum at the Giardini Pubblici, opened in 1878, the works of the Marchesi collection were then transported to the Castello Sforzesco restored by Beltrami in the early twentieth century to become the seat of the civic museums, and then divided among the various institutes gradually founded: from the Archaeological Museum to the Cabinet of Drawings, from the Museum of Ancient Art to the Art Library to the Achille Bertarelli Collection of Prints, which still preserve them today. The largest number of works is kept by the Gallery of Modern Art: the museum was inaugurated in 1903, but its founding nucleus is to be traced precisely in Marchesi’s collection.

The exhibition therefore aims to reconstruct the complexity of the collection and its importance for the birth of the city’s art collections, in which it is deeply innervated, making use of the contributions of the civic institutes: the Gabinetto dei Disegni, the Raccolta delle Stampe “Achille Bertarelli,” the Biblioteca d’Arte, the Civico Archivio Fotografico, and the Museo d’Arte Antica del Castello Sforzesco. Marchesi’s sculptures in the Gallery of Modern Art are thus juxtaposed for the first time with a selection of paintings, drawings, engravings and books by various artists close to him. In this way it has been possible to further enhance the richness and complexity of Milan’s civic collections whose valuable and active collaboration has enabled new discoveries and attributions.

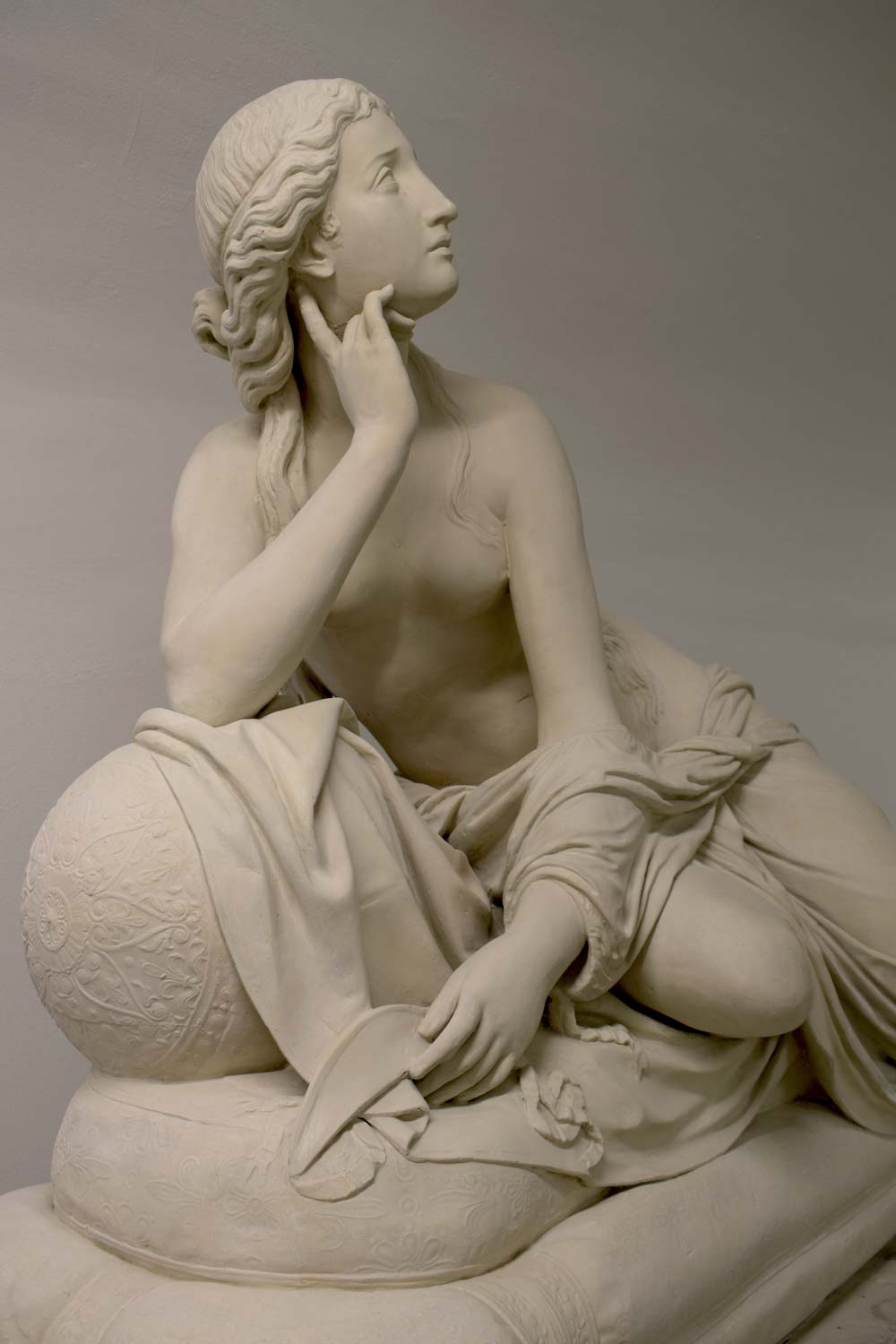

The exhibition is also an opportunity to show the results of an extensive restoration campaign on Marchesi’s sculptures, sketches and terracottas-with particular reference to the city’s major enterprises. Restored works, including The Genius of Hunting, Magdalene, terracottas for the Arch of Peace and plaster casts for the monument of Francis I in Vienna, are thus juxtaposed with preparatory drawings, sketches and engravings by the artist and with previously unpublished and never exhibited works from the deposits of the Gallery of Modern Art. What emerges is not only the profile of one of Canova’s most important sculptors, but also his complexity as a collector. Many of the sketches, plaster casts and models are on display for the first time: some bear the marks of the 1834 studio fire. The execution technique used by Marchesi is the one developed by Canova in the late 18th century and then adopted by all sculptors until the 20th century. The first idea found form in a small sketch, modeled in clay and then fired or translated into plaster, which was followed-sometimes with intermediate steps-by the creation of a carefully finished plaster model on a 1:1 scale, on which crosses or pegs, still visible, were affixed to bring the dimensions back to the block of marble to be sculpted.

Marchesi also introduced contemporary dress into official sculpture, which was still stuck on classicist positions, between heroic nudity and old-fashioned drapery, affirming instead the right of every age to self-representation. On the other, he instills in the figures a delicate emotional and sentimental dimension, manifestly romantic, evident in works such as the Magdalene or in funerary monuments. In the latter, there is a transition from the initial adherence to the Canova modules of the classical stele and mourning to the archaic simplification of Thorvaldsen’s bas-reliefs. The comparison of studies, sketches and finished models makes it possible to reconstruct entire iconographic series and to follow the development of the work from the first idea to its final realization, through afterthoughts and modifications. The contrast between the unexpected strength of the almost anticlassical sketches and the polished perfection of the plaster casts seems to translate Wickelmann’s instruction to “conceive with fire, but execute with serenity.”

An unexpected feature in Pompeo Marchesi’s collection is then thelarge presence of drawings, works that the sculptor researched with great passion throughout his life, preserved at the Castello Sforzesco’s Drawings Cabinet. In addition to the nuclei of drawings by those he considered his masters-displayed in the previous rooms-Marquessi collected a large number of works by his contemporaries, giving the collection an extremely modern character for the time, especially for an artist considered a classicist. Thus, next to Bossi and Appiani, we find Luigi Ademollo, Giovanni De Min, Federico Moja, Pelagio Palagi, Francesco Sabatelli, a conspicuous nucleus of drawings by Vitale Sala, a pupil of Palagi who died very young, to which must be added foreign artists, such as Kupelwieser or de Sequeira, and some drawings of stage sets and architecture, by Gaetano Vaccani, Paolo Landriani, and Giovanni Perego. To his friend Francesco Hayez belongs perhaps the most beautiful drawing in the collection, the sensual Bathsheba at the Bath. There are many works by artists whom Marchesi knew and frequented. Their acquisition must have been the result of gifts, exchanges, travel or direct purchases. The collection of drawings shows a predilection for finished drawings and mythological and romantic subjects. The drawings were collected and selected in the environment experienced by Marchesi, between Lombardy and Austria, for their aesthetic qualities, with mainly collector purposes: they are not sheets and works for the use of the workshop, as was the custom in the Renaissance, but the result of Marchesi’s taste, and in fact perfectly consistent with his aesthetics. This does not exclude the possibility that they could, however, also be pointed out to his pupils as models or that they were a source of inspiration for the sculptor.

|

| From Neoclassicism to Romanticism: an exhibition on Pompeo Marchesi at the GAM in Milan |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.