Emilio Isgrò rereads Leonardo da Vinci's Battle of Anghiari. I will try to make a work that speaks to many

From May 1 to August 4, 2019, the Museum of the Battle and An ghiari (Anghiari, Arezzo) hosts a confrontation between two great artists, one of the past and one of the contemporary: Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) and Emilio Isgrò (Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, 1937). In particular, the Sicilian artist confronts one of Leonardo da Vinci’s most important works (although known only from studies and reproductions), the Battle of Anghiari. Isgrò undertook the task of tackling the theme of Leonardo’s battle by trying to interpret the great Tuscan artist’s state of mind, taking a close look at his human, historical and artistic life, in order to come up with a universal key to interpretation, capable of offering multiple contemporary interpretations. The exhibition, titled Emilio Isgrò for Leonardo da Vinci’s Battle of Anghiari, thus offers the public an unpublished work by Isgrò, specially created for the occasion. The exhibition also traverses the anniversary of June 29, the day on which, in 1440, the Florentine army clashed with the Milanese army on the plain near Anghiari (the victory would be reported by the Florentines).

The Battle of Anghiari harkens back to the framework of the Wars of Lombardy, the series of conflicts that for about thirty years, from 1423 until the Peace of Lodi in 1454, the Duchy of Milan, as part of its policy of expansion, fought against the Republic of Venice and its allies (which included, until 1450, the Republic of Florence, which then in turn allied itself with Milan starting that same year). At Anghiari, the Visconti army led by the condottiere Niccolò Piccinino, a Perugian hired by the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, had to succumb to the Florentine-Venetian forces (commanded by Micheletto Attendolo, Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo and Ludovico Scarampo Mezzarota), numerically superior (they numbered over nine thousand against the thousand of the Milanese, to which was added a contingent of two thousand men from nearby Sansepolcro): near the Tuscan village, after four hours of grueling battle, the coalition formed by the Venetians, the Florentines and the militia of the Papal States, managed to prevail, and thanks to the victory the Florentines were able to consolidate their domination over Tuscany.

But the Battle of Anghiari has gone down in history mainly because of the depiction imagined by Leonardo da Vinci, and which today, however, we know only indirectly. In 1503, the Republic of Florence commissioned him and Michelangelo Buonarroti to paint two scenes to be frescoed on the walls of the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, two significant episodes in Florentine history: Michelangelo was commissioned to execute the Battle of Cascina, while Leonardo was commissioned to paint the Battle of Anghiari. However, neither of them completed the work: in fact, Leonardo experimented with a technique similar to the one he had used for the Last Supper in Milan, not availing himself of the use of fresco, but resorting to a wall painting to be dried by heat. In order to succeed, Leonardo set up two large pots fueled by wood to reach the high temperature that would dry the paint as soon as possible: however, the room was so vast that the artist was unable to obtain the necessary temperature before the paint leaked, irreparably ruining the painting. Leonardo thus abandoned the work: today we do not even preserve the cartoons, but we know the Battle of Anghiari through some studies and reproductions by other artists (for example, the very famous Tavola Doria, attributed by some to Leonardo da Vinci himself, although this is a hypothesis not shared by critics). For his work, Leonardo chose to focus on a particular moment of the battle, that of the struggle for the standard, in which both the commanders of the Milanese army (Niccolò Piccinino and his son Francesco, depicted with contorted faces in violent, almost feral grimaces) and those of the Florentine troops (Ludovico Scarampo Mezzarota and Pietro Giampaolo Orsini) are involved, with, at the bottom, two soldiers fighting ferociously.

|

| The Village of Anghiari |

|

| Anonymous, copy from the Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo (16th century; print) |

“A compendium of all Leonardo’s knowledge,” Carlo Pedretti, among the all-time leading specialists on the artist from Vinci, has written in the past, the Battle of Anghiari represents, for this very reason, an “absolute, if fragmentary and soon to be lost masterpiece, capable of casting blinding glimmers of novelty that struck deep into the minds of the stewards. It is no accident that artists of the caliber of Raphael, Michelangelo or Rubens were strongly impressed by it. [...] Leonardo’s purpose was to succeed in depicting in a single image a story full of movement and not synchronous, an episode dense with particular situations with outcomes already implicit in the acts depicted and charged, moreover, with symbolic and moral significance. A drawing of such ambition that no one could have described verbally more effectively.”

“Approaching a Leonardesque work of considerable size, which, moreover, no longer exists, assuming it ever existed, since Leonardo always had problems with materials and their resistance, means, for an artist, facing a problem that is not simply one of marketing, but is also made up of content that transcends marketing,” said Emilio Isgrò. “It simply means to consider art a form of challenge to one’s humanity, to one’s being in the world, and to the need to consider the moment when politics apparently no longer has any tools to act, to consider art itself a form of politics, indeed the highest form of politics.”

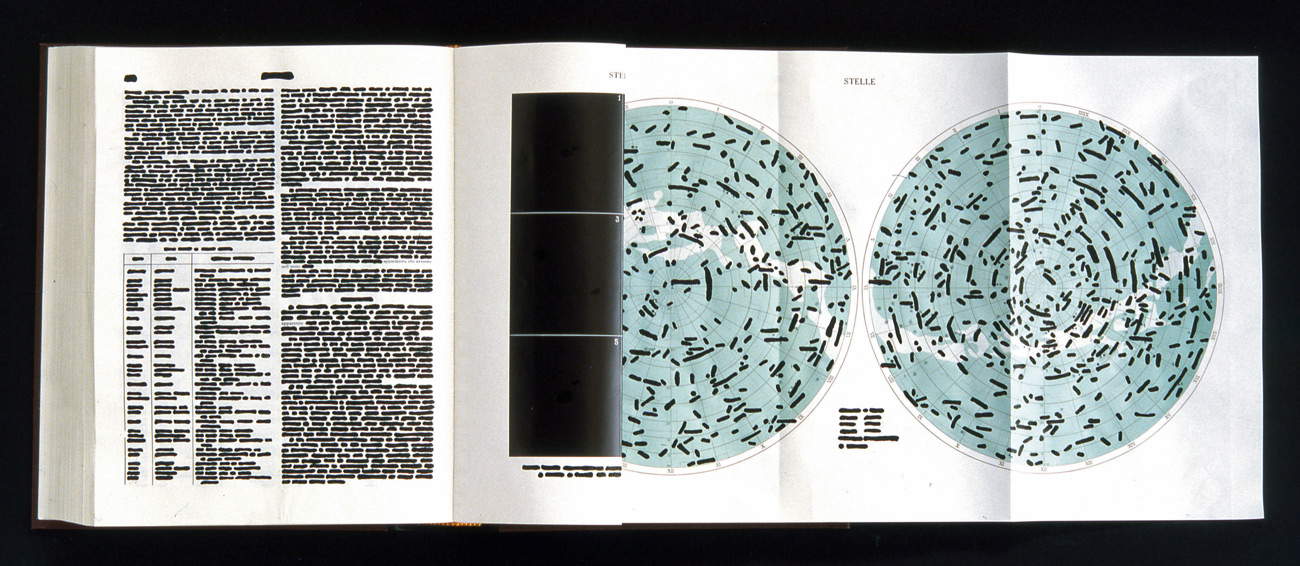

Emilio Isgrò is one of the most internationally known and prestigious Italian artists. A poet, writer, playwright and director as well as a visual artist, since the 1960s he has naturally and necessarily turned his professional career, which included activities as an editor and journalist, toward a new and original language. In fact, the artist created his first works in 1964: the “erasures” of texts, applied on encyclopedias and books, which became his best-known and most recognized form of expression. Isgrò would later decline the peculiar and recognizable stroke on cartographies and even on cinematographic films. His work is a fundamental contribution to the birth and developments of visual poetry andconceptual art. “Erasure,” says the artist, “is not a banal negation but rather the affirmation of new meanings: it is the transformation of a negative sign into a positive gesture.”

|

| Emilio Isgrò, Enciclopedia Treccani (vol. XXXII), 1970 |

|

| Emilio Isgrò, Paper, 1972 |

“I will try, with my work, to make a work that speaks to not say everyone, but to a large number of people,” Emilio Isgrò added about his work for Anghiari. “I realize that my work is quite a two-faceted, multi-faceted work: the erasure itself, just to point to the most well-known part of my work, in itself is nothing but an erasure, so apparently easy, and in fact the erasure is the reversal of language when language no longer speaks. It is an ecological operation of the mind, of languages, of words, and of images themselves. But it has a fortune compared to other gestures of very good artists: erasure reaches the public, precisely because I since I was a boy did not want to create such sophisticated art that would speak only to critics and certain collectors. I tried to create art that could also speak to people who go to a museum and get there alone or almost alone, with little explanation. Because there are forms of art that in the twentieth century, for example a part of conceptual art, that fifty years after its birth still needs to be explained. I, on the other hand, am for an art form that given the key and explained once, then doesn’t need it anymore, because the rest comes by itself.”

The exhibition is organized under the auspices of the National Committee for the Celebration of the 500th Anniversary of the Death of Leonardo Da Vinci, under the patronage of the Italian Touring Club and with the support of the Region of Tuscany. The Museum of the Battle of Anghiari opens during the exhibition period every day from 9:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 2:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. More information is available on the website of the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari. In order to attend the opening, which will take place on May 1 at 11:30 a.m., it is necessary to book your attendance free of charge.

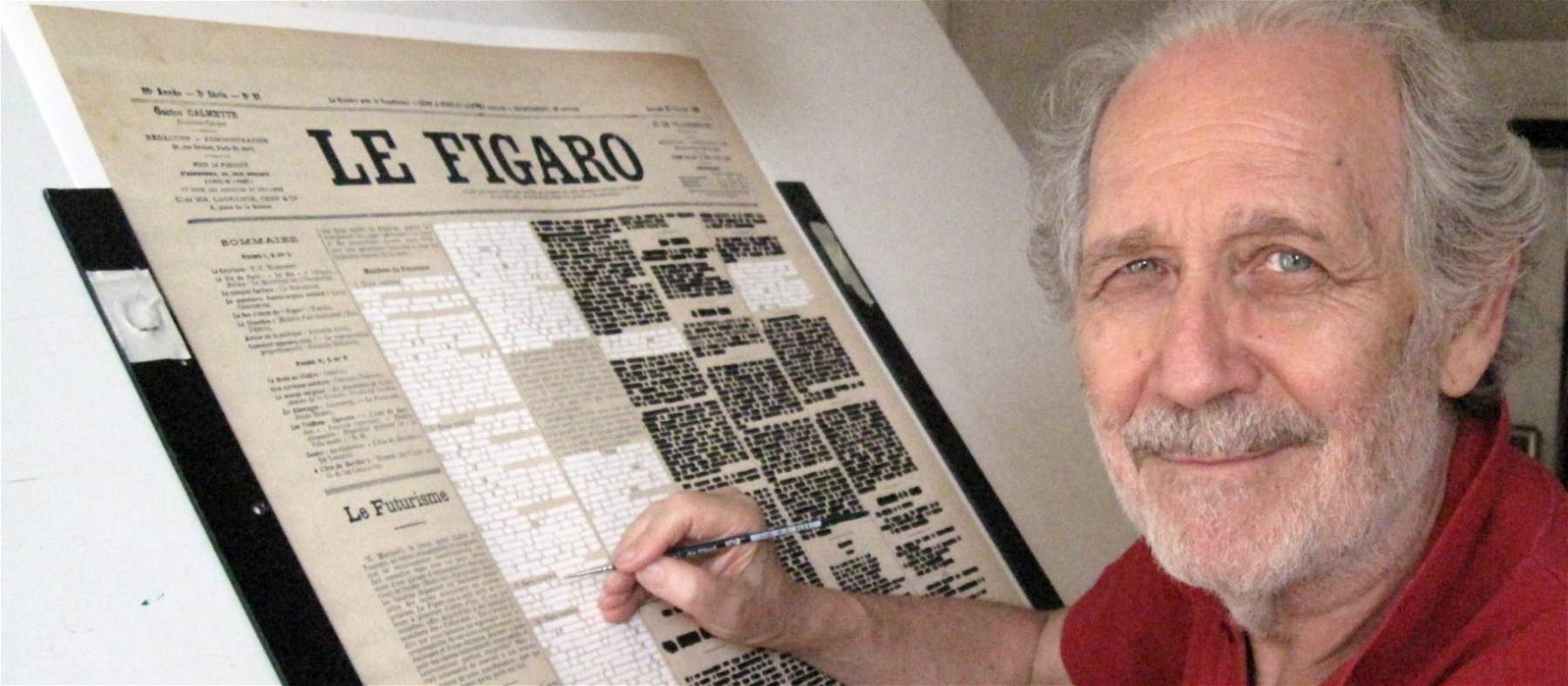

Pictured below: Emilio Isgrò clears the futurism manifesto.

|

| Emilio Isgrò rereads Leonardo da Vinci's Battle of Anghiari. I will try to make a work that speaks to many |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.