Eleven major contemporary Italian sculptors measure themselves against Canova at Possagno

On the occasion of the two hundredth anniversary of Canova’s death, The Gypsotheca Antonio Canova Museum has chosen to employ its spaces in the promotion and celebration of the Artist through a series of exhibitions. A path that indicates the contemporaneity of the great masters and their ideas with the interpreters of our time.

The exhibition Antonio Canova and Contemporary Sculpture is part of these celebrations and recounts the challenge of a number of contemporary sculptors, all of whom competed with Canova: Marcello Tommasi, Wolfgang Alexander Kossuth, Girolamo Ciulla, Giuseppe Bergomi, Giuseppe Ducrot, Filippo Dobrilla, Livio Scarpella, Ettore Greco, Aron Demetz, Fabio Viale and Jago.

The project, conceived by Vittorio Sgarbi, is realized by Contemplazioni, in collaboration with the Gypsotheca Antonio Canova Museum, thanks to the support of Intesa Sanpaolo.

Canova is certainly the greatest exponent of neoclassical art, with his taste for perfect symmetries, soft and smooth surfaces, solemn and controlled poses, and impassive expressions. He did not passively imitate the antique, preferring to interpret its spirit, nor did he close himself off from Baroque art, as his youthful admiration for Bernini and Antonio Corradini reveals.

Born into a family of artists, Marcello Tommasi is considered the “symbolic heir of fifteenth-century Neoplatonism.” It was between 1948 and 1958, when he frequented Pietro Annigoni’s studio, that Tommasi drew, painted and gradually turned his efforts to sculpture. He lived mainly between Florence and Versilia, moving often to his beloved Paris. A master of figurative art, he works extensively in both sacred and secular art, often taking inspiration from Greek myths. His enormous output includes hundreds of works including drawings, sketches, sculptures, paintings and frescoes.

Wolfgang Alexander Kossuth’s is a style of great contrasts, indulging and denying naturalism at the same time. Painter, sculptor, violinist and conductor, Kossuth devoted his entire life to art, blending his passions and making figuration the foundation of his poetics. Pathos and theatricality ooze from the twisted bodies, in resin or bronze, that defy the laws of gravity to the limits of the surreal; sometimes idealized to the point of recalling Greco-Roman gods, others so expressive as to recall the reality of the everyday.

Girolamo Ciulla’s myths and legends are not the stories we know, but the dream of those stories that his imagination transforms into new images and tales. Ciulla does not illustrate, but creates myths in his own image. He was born in Caltanissetta, and his ties to his homeland lead him to elaborate a sculptural syncretism that looks to antiquity, myths, and Italic, Greek and Oriental archetypes. His sculptures, however, have nothing nostalgic about them: Ciulla dialogues with classicism by elaborating a contemporary lexicon, to show that ideas live beyond men and beyond time.

Giuseppe Bergomi’s sculpture prominently reproposes figurative research as a response to the conceptual, minimalist and poverist temperament of the 1970s. Bergomi brings back to center stage the strict sense of a corporality that is both technical discipline and poetic research. His new sculptures follow the long furrow already traced by an extensive production and at the same time seek a new dialogue with matter, particularly ceramics and mosaic, employed to renew themes and forms dear to him, such as portraits of bathers and reclining figures. His works thus untouched and untouchable achieve an absoluteness that seems to contradict or abolish reality but instead derives precisely from that profound identification with the real.

Bernini’s heir is Giuseppe Ducrot. An original artist capable of unpredictable inventions. An ancient sculptor who seems to have resumed his efforts and his work where Gian Lorenzo Bernini stopped; and thus with a moved form, with an extraordinary taste in detail and a corresponding capacity for execution, he can, in a church, insert a candelabra, a pulpit or an altar that seems consecrated by history. And this ability of his is extremely rare for a sculptor.

Filippo Dobrilla is a little eccentric, a little crazy; he has carved a Babel-sized Giant - a symbol of one man’s love for the grandeur of the world - in the very belly of the Apuane Mountains, remaining submerged for weeks at a time, beating his chisel with a mallet on the bare, monolithic, rock. He knew the stone deep inside, from within, studying it in the bowels. Instinctively he could recognize its sags, its purity, its crystalline verse because he had experienced these places like no other among sculptors.

Among the most ingenious and cruelly ironic sculptors of our time is Livio Scarpella, who pursues a morbid homosexual imagery, dominated by unconscious “bad boys” who would have enchanted Saba, Penna, Pasolini, and whom he puts before us with smug virtuosity and sublime naturalness. Sin, without penitence and with complacency, is the state of mind in which he stirs, troubled but euphoric, pursuing and representing bad thoughts that turn into delights of style, luciferous beauties, unspeakable and unforgivable mischief. His spirit is Dionysian, his form Apollonian. The synthesis is perfectly successful. Thus, as in these comparisons, his revisiting of History.

A bluesman of clay, Ettore Greco narrates his relationship with the material in analogy to that of a guitarist improvising a melody: his fingers move over the sculpture without a predefined score, but in an act of creation that is always spontaneous and seeks, as its ultimate goal, feeling. The Paduan sculptor, who has chosen to remain faithful to the figurative tradition, is able to explain man as he is, beyond time, because he accepts him without judging him. His sculptures are a hymn to humanity.

The work of South Tyrolean artist Aron Demetz has always focused on the transformation of matter, in a thoughtful confrontation with classical art aimed at defining new expressions of plasticity. Life-size human figures in wood, bronze and plaster, covered with resin, charred and wildly frayed are arranged in his studio. What characterizes Aron Demetz’s art is the subtle communication of his human figures with the viewer: they seem to peer at him, it is almost annoying to look at them. Aron Demetz is among the most prominent sculptors on the international scene, but this does not deter him from his tranquility: he does not leave Val Gardena, because that landscape is part of his art.

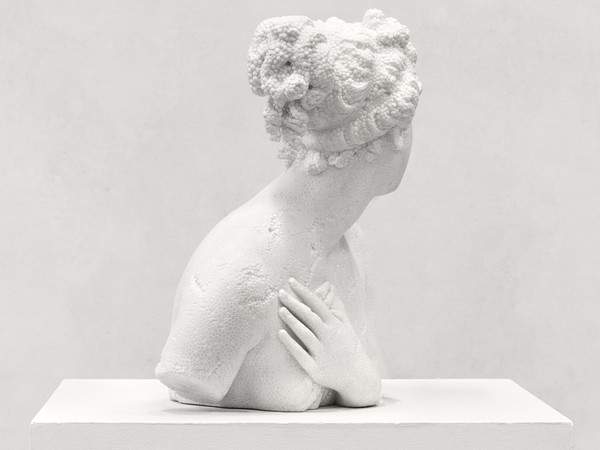

Fabio Viale replicates masterpieces of Western art with dizzying precision, echoing the well-known tradition of copyist sculptor workshops. As then, so in Viale, the theme of copying adds quality, thanks to the thoughtful choice of subject and display of sculptural skill, and especially thanks to the gesture of contemporary reinterpretation. Fabio Viale has never tired of experimenting with the potential of marble in faithfully replicating objects that our reason refers to an entirely different material. His extraordinary technical skill has enabled him to create fictions of the materials that are so credible in finish, color and texture that he is able to induce the viewer to an irrepressible desire to touch them to verify their real nature. Here Viale’s work appears as a stimulating oxymoron: that which seems noble and eternal is the result of skillful deception, while that which seems to us a simple product of today in customary materials is actually molded in the noblest and most eternal of substances.

Jago is an artist with multifaceted appeal who has been much talked about. His art from the web has reached all the way to the Vatican, which commissioned him to create a bust for His Holiness. The portrait of the Pope and his other works are a sign of a discipline that so few artists have demonstrated in the twentieth century. Jago works marble as if it were plasticine or plaster. His works literally come to life thanks to the minute details he can sculpt, especially when he goes to recreate facial wrinkles and skin folds.

The exhibition stages a hand-to-hand between contemporary sculpture and the neoclassical sculpture of Antonio Canova, not in the name of imitation, but in the sculptural search for the “real flesh” - that which the Artist admired, in turn, in the works of the great classical master Phidias.

For all information, you can visit the official website of the Gypsotheca Antonio Canova Museum.

Pictured: Fabio Viale, Venus italica (2016). Private collection.

|

| Eleven major contemporary Italian sculptors measure themselves against Canova at Possagno |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.