Bergamo hosts first-ever exhibition on Cecco del Caravaggio, Merisi's mysterious pupil

From Jan. 26 to June 4, 2023,Bergamo’s Accademia Carrara presents, in the museum’s renovated spaces, the first exhibition ever dedicated in Italy and the world to Cecco del Caravaggio (Francesco Boneri, c. 1585-after 1620), Caravaggio’s most mysterious pupil and model. The exhibition, entitled Cecco del Caravaggio. The Model Pupil and curated by Gianni Papi and Maria Cristina Rodeschini, counts on the presence of 41 works: 19 of the approximately 25 known paintings by Cecco, 2 works by Caravaggio, and, together, artists who inspired and were inspired by this fascinating painter, with national and international loans from Berlin, London, Madrid, Oxford, Warsaw, Vienna, Brescia, Florence, Milan, and Rome.

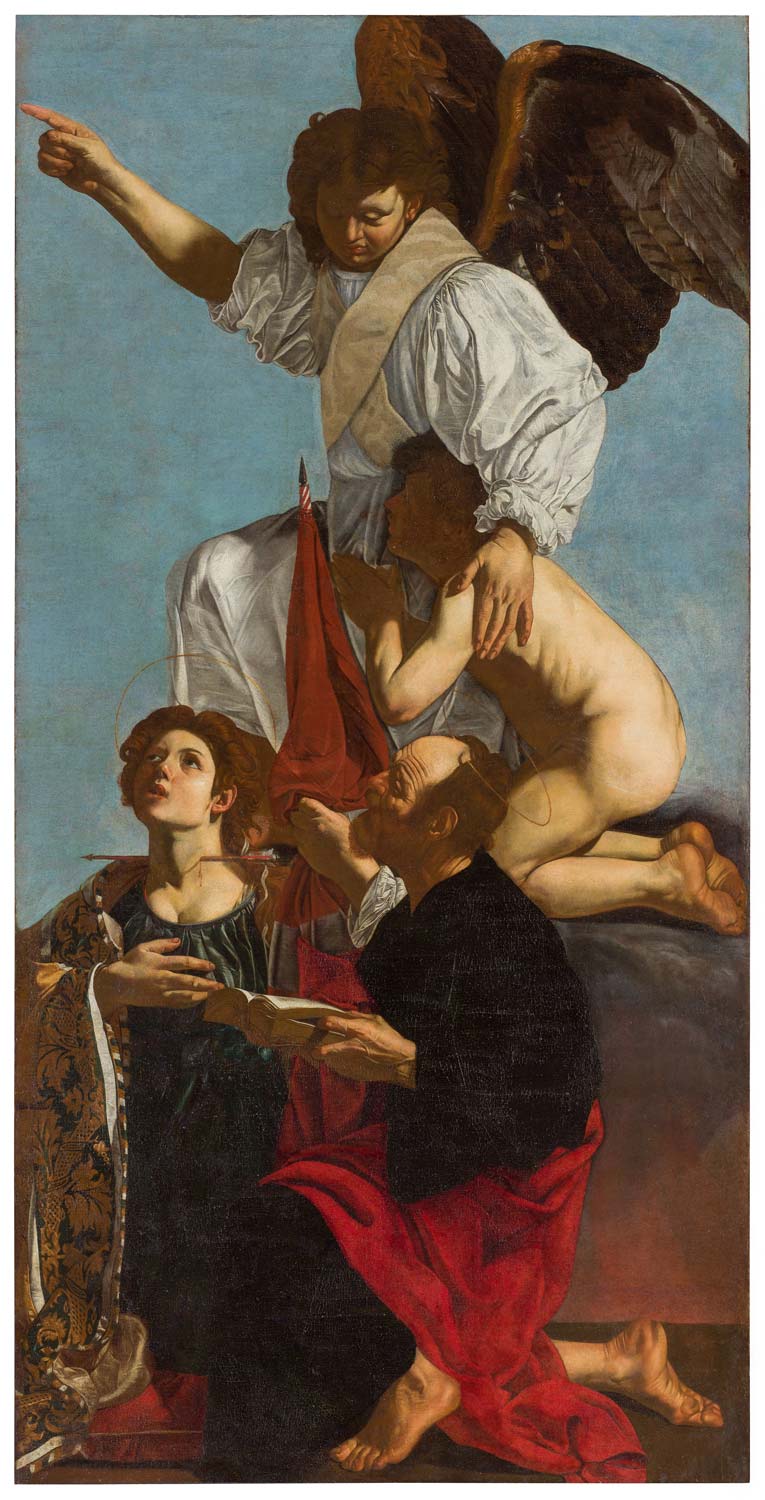

Cecco del Caravaggio is known to have been the model for many of Michelangelo Merisi’s masterpieces: he is indeed the irreverent and playfulLove Winner in Berlin, he is the sensual St. John the Baptist in the Capitolina, he is most likely the screaming altar boy in the Martyrdom of St. Matthew in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, he is the angel in the Conversion of St. Paul in the Odescalchi collections, he is David displaying the severed head of Goliath in the Borghese painting, and Goliath is Caravaggio. He is “his boy,” the boy “that laid with him,” as told by an English traveler in the mid-seventeenth century. He is the painter who more than others takes the master’s lesson to extreme, free, nonconformist consequences, and he is also the author of compositions that point the way to an ante litteram hyperrealism.

Atypical, intolerant of rules, destined to provoke contrasts and perhaps enmities, though all but absent from historical and judicial chronicles (unlike most of his colleagues in the Caravaggesque circle), the enigmatic figure of Caravaggio’s Cecco appears as a nonconformist, capable of resounding innovations in iconographic frameworks, a virtuoso of extraordinary painting, relentless in the definition of forms, contours, and color, an outspoken naturalist, bold, overbearing, and devoid of censorial fears, at times explicit in erotic references and homosexual messages.

Most likely born within the territory of Bergamo, he was for years considered Flemish, French or Spanish; Roberto Longhi wrote of him that he was "one of the most remarkable figures of Nordic Caravaggism,“ whereas now thanks to updated studies, that ”Nordic" must be understood as from northern Italy, and no longer Europe. The case of Cecco del Caravaggio is relatively recent: the new studies initiated by Gianni Papi since the 1990s, as well as the milestones achieved, among them the discovery of some works, show how art history is a living and lively matter, capable, if pursued, of continually renewing itself even against the sort of damnatio memoriae that soon affected Boneri’s artistic affairs; a kind of systematic neglect that today could fall within the broad spectrum of Cancel Culture.

For Cecco there is not only an absence of sources but also a series of misinterpretations: to the initial confusion with respect to its provenance, now however explained by Gianni Papi also thanks to the many points of contact with the painting of Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo (Brescia, c. 1480-post 1548) who, between naturalism and classicism, can be considered Cecco’s second great inspirer, an explanation of his nickname has been added over the decades that is far from the most logical meaning, namely that “of Caravaggio” simply alludes to a dimension of closeness, almost of belonging. In favor of this thesis is the passage from the aforementioned English traveler who was present in Rome around 1650: the passage also reveals much with respect to the fact that the model of Amor Vincit Omnia was none other than the future painter Cecco, as well as giving confirmation to the controversial question of Caravaggio’s homosexual inclinations.

What is certain is that the apprenticeship in Caravaggio’s studio must have been very different from that of the Florentine or Roman workshops: almost without rules, pupils learned to paint by observing the master, always portraying models from life, mixing craft and life experiences. Cecco’s apprenticeship repeated the path that had already been his master’s, namely, that of entering, as a boy, the studio of an established artist from the same area of origin: Simone Peterzano for Caravaggio, Caravaggio himself for Cecco. Francesco Boneri thus lived side by side with Caravaggio; he is mentioned in some sources as “Francesco garzone” or “his Caravaggino” or “Francesco detto Cecco del Caravaggio” in Caravaggio’s “schola” along with Ribera, Spadarino and Manfredi, to this day considered the four painters closest to the master. Cecco figures as a model for at least six of Merisi’s paintings, including the St. John the Baptist in the Pinacoteca Capitolina and David with the Head of Goliath in the Galleria Borghese, which will be on display.

The itinerary highlights both authors, such as Merisi and Savoldo, from whom Cecco drew inspiration, and a series of artists who were close to him (including Valentin de Boulogne, Bartolomeo Mendozzi and Pedro Núñez del Valle), through loans from mainly public collections: Uffizi Galleries-Palazzo Pitti in Florence, Prado Museum in Madrid, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, National Gallery in Athens, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Palazzo Barberini in Rome, Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, Galleria Borghese and Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome, Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia, Wellington Museum in London, Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, to name a few.

The Bergamo exhibition aims to offer for the first time a cross-sectional and almost complete look at Cecco’s work, bringing togethermasterpieces that have proven to be fundamental in the reconstruction of the author’s corpus. In particular, the Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple (ca. 1613-1615), from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, played an essential role in determining the very first nucleus of works by Roberto Longhi and thus in defining the identity of the pictorial language. The canvas expresses adherence to the great masters: on the one hand, Caravaggio, in the bustling composition and the figures’ expressions of terror, and on the other, Savoldo, in the sharp, crisp atmosphere, the pure colors, and the twisted, crushed draperies. Gianni Papi has identified a self-portrait of Cecco in the elegant young man on the far left who, with a defiladed and somewhat dandy attitude, observes the scene. The red hat worn by the young man is a recurring theme in the early works and can also be found, in the exhibition, in canvases from Warsaw and Bratislava; just as it is possible to trace the elegant fashions of the merchants’ clothes in the figure paintings on loan from Athens, London and Oxford.

We are also familiar with the painter’s face thanks to Portrait of a Young Man with Lettuce Collar, from Gallerie degli Uffizi - Palazzo Pitti in Florence in the protagonist ofLove at the Fountain, from a private collection, as well as thanks to the two paintings by Caravaggio in the exhibition, for which, as mentioned above, Cecco posed as a model. Within the exhibition itinerary, from work to work, Boneri’s language becomes increasingly recognizable: in the tormented execution of the draperies, in the whites with phosphorescent intensity, in the precise definition of the eyes and eyelids, and in the sharp drawing of the lips furrowed by a thick line that makes them seem open, engaged in a song, a sigh, a stifled cry.

If Cecco’s life is still shrouded in mystery, the same cannot be said, thanks in part to this project curated by Gianni Papi and Maria Cristina Rodeschini, about the influences the painter received and exerted, the latter especially on the Roman and Neapolitan scene of the time (in fact, it is speculated that Boneri followed Caravaggio in his flight to Naples after the murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni in May 1606). As well as that of Bergamo, the province where he was probably born and perhaps returned to at some point in his career.

Considered among the great protagonists of Caravaggesque still life, along with Bartolomeo Cavarozzi and Antiveduto Gramatica, Cecco was also to influence the research of Evaristo Baschenis (1617 - 1677). The Bergamasque-born priest-painter, widely represented in the collections of Accademia Carrara, is certainly indebted to Boneri’s masterly lesson in the realism of the still life pieces and the rendering of musical instruments in the Fabbricanti series. In the exhibition, the comparison between the two authors is fostered through a work on loan and, within the permanent itinerary, in the room dedicated to Baschenis.

Caravaggio’s Cecco. The Model Pupil, the first exhibition to occupy the museum’s new spaces dedicated to temporary projects, in addition to shedding light on an important author, also aspires to restore attention to those “painters of reality” of Lombard origin - according to Roberto Longhi’s definition - to whom it seeks to restore their rightful place in the European artistic panorama of those years.

“Cecco stands out for a hyperrealist and nonconformist depiction, sharp and restless, saturated with a dense and shiny pictorial matter,” says Gianni Papi. “A peculiar stylistic figure: like him, no one handles and constructs figurative interrogatives (for us, four centuries later, armored and cryptic), coating them with an exaggerated naturalism.”

“Cecco’s exhibition,” Maria Cristina Rodeschini points out, “presents a painter who deserves to enter the Olympus of the most interesting Italian Caravaggesque painters. His more than likely origin in the territory of Bergamo is one more reason for having made this choice. Moreover, the painter’s interest in Savoldo’s magnificent painting and the influence he exerted on Evaristo Baschenis, declines a trait d’union between Brescia and Bergamo - cities and territories that in 2023 will together have the title of Italian Capital of Culture - of sure perspective.”

All information can be found on the Accademia Carrara’s website, https://www.lacarrara.it/.

|

| Bergamo hosts first-ever exhibition on Cecco del Caravaggio, Merisi's mysterious pupil |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.