At the Musée d'Orsay, a major exhibition compares Manet and Degas

An exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris that compares the work of Édouard Manet (Paris, 1832 - 1883) and Edgar Degas (Paris, 1834 - 1917) opened last March 28 and will run until July 23. The exhibition, titled simply Manet / Degas and which will then move from September 2023 to January 2024 to the Metropolitan in New York, assumes that bringing together crucial artists such as Manet and Degas cannot simply identify the similarities offered by their respective corpuses. Certainly, among these essential protagonists of the new painting of the 1860s-80s, there is no shortage of similarities with regard to the subjects they imposed (from horse racing to café scenes, from prostitution to the toilet), the genres they reinvented, the realism they opened up to other formal and narrative potentialities, and then again the market and the collectors they managed to tame, the places (cafes, theaters) and the environments, familiar (Berthe Morisot) or friendly, in which they met.

Before and after the emergence of Impressionism, on which the exhibition (curated by Laurence des Cars, Isolde Pludermacher, Stéphane Guégan, Stephan Wolohojian and Ashley E. Dunn) intends to open a new look, it is even more striking what differentiated or contrasted them. Of different backgrounds and temperaments, the two artists did not share the same tastes in literature and music. Their divergent choices in terms of exposure and career cooled, from 1873 to 1874, the burgeoning friendship between them, a friendship strengthened by their shared experience of the war of 1870. One cannot compare the former’s quest for recognition and the latter’s stubborn refusal to use official channels of legitimacy. And if we consider the private sphere, past the years of youth, everything separates them. Manet’s sociability, very open and immediately quite brilliant in his domestic choices, is answered by Degas’s isolated existence.

In Degas Danse Dessin, where much is said about Manet, Paul Valéry speaks of these “wonderful cohabitations” that border on dissonant chords. Because it brings Manet and Degas together in the light of their contrasts, and shows how much they define themselves by distinguishing themselves, the Musée d’Orsay exhibition, filled with masterpieces never brought together before, aims to force the public to look with different eyes at the short-lived complicity and enduring rivalry of two giants.

The exhibition is divided into fourteen sections. The first is titled L’énigme d’une relation: Manet and Degas saw each other regularly and frequented the same circles, but we do not know the date of their meeting and retain almost no correspondence from one another. The writings of their contemporaries and biographers describe their relations in which admiration and irritation, friendship and rivalry are mixed. Degas portrayed Manet often, while we know of no depiction of Degas by Manet. The latter allegedly cut off the part of the canvas offered by Degas where his wife was depicted at the piano, a gesture that would be the origin of one of the most famous estrangements between the two artists.

We continue with the Deux fils de famille section: born in Paris in the early 1830s, Manet and Degas were the eldest sons of wealthy bourgeois families. Manet’s father is a high-ranking official; his mother is the daughter of a diplomat. The Degas family belongs to the business and financial community. Devoted to legal studies, Manet and Degas both abandoned them to follow their artistic vocation. They then each studied with recognized painters but outside the École des Beaux-Arts, apart from Degas’ brief passage; it is a possible sign of an early desire for independence, and certainly reveals their high social status. The third section, Copier, créer, étudier, starts with the “legend” of Manet and Degas meeting at the Louvre Museum in the early 1860s in front of a Velázquez canvas that Degas was copying. Both had been regulars at the museum since childhood. During their formative years, their apprenticeship was based in part on copying the old masters at the Louvre. They also traveled to perfect their artistic culture, especially to Italy. As for contemporary masters, they admired Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. Beyond appropriation by copying traditional knowledge, references to the art of the past are declined in their own production in forms ranging from quotation to homage to pastiche. It then continues with the fourth section Salon et défi des genres: no novice could escape the Salon under the Second Empire. It became annual in 1863, its jury is more liberal after 1867. This event inherited from the Ancien Régime brings together thousands of paintings, sculptures, works on paper. The Salon was then in France the main exhibition venue for living artists and almost the only opportunity to be seen by the Fine Arts Administration. It was at the Salon that state patronage manifested itself through purchases, prizes and encouragement. Manet was admitted there in 1861, Degas in 1865.

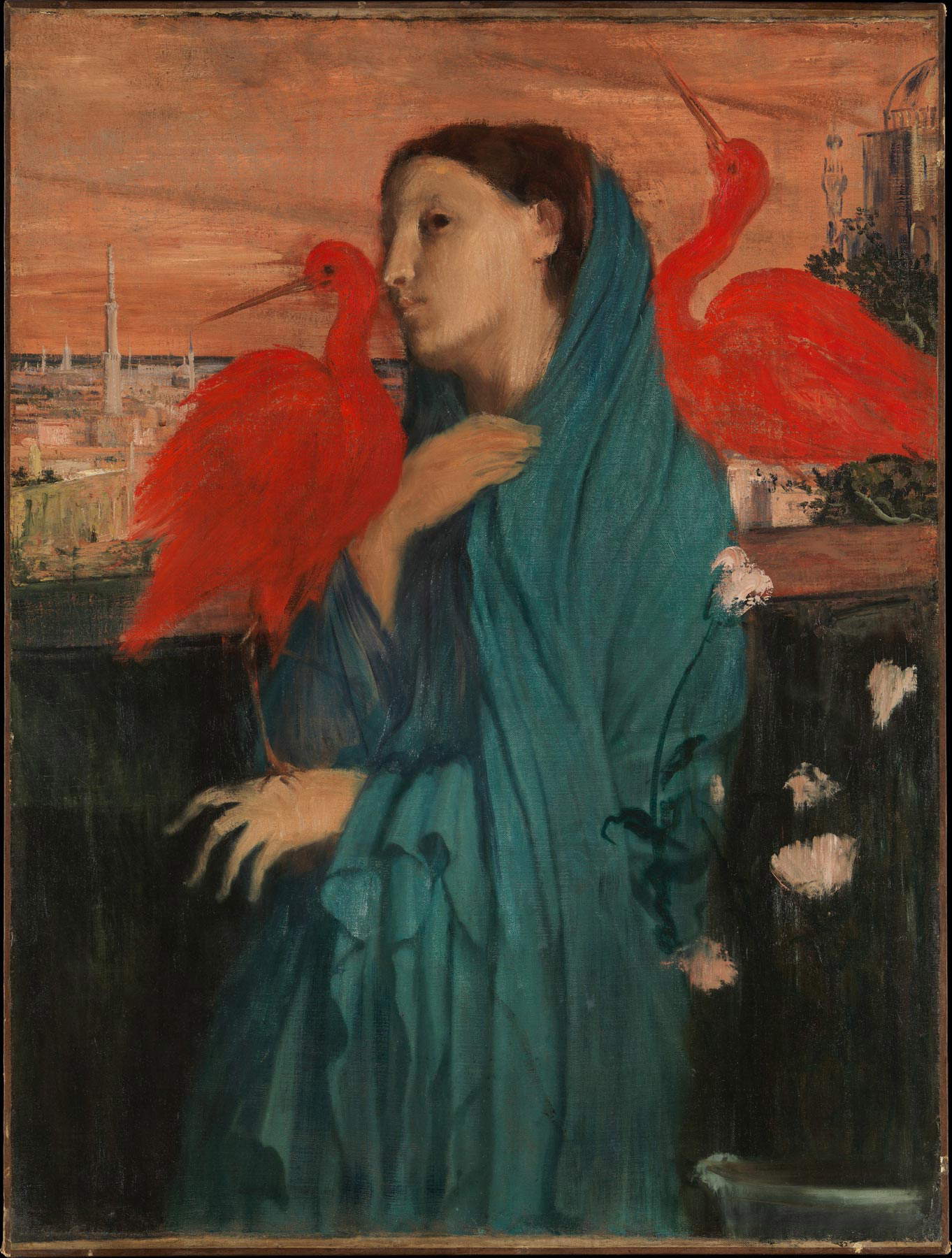

Instead, the fifth section, Au-delà du portrait, is devoted to portraiture: very much in vogue during the Second Empire, the portrait occupies an important place in Manet and Degas’ early production. As painters of modern life, they find a way to capture the essence of their time. Their models are relatives or, for the Salon, public figures, thus emphasizing their ties to certain social or artistic circles. Manet places his subjects at the center of the composition, often in poses inherited from the Old Masters, and uses bright colors. Degas uses a darker palette, interested as much in the expression of bodies as in that of faces. The sixth section(Le cercle Morisot) is about the salon that Berthe Morisot’s parents opened to artists. A hotbed of modernity: women and men talk about art or politics on an equal footing. Berthe and her sister Edma, trained as painters, debuted at the Salon in 1864. But it was their meeting with Henri Fantin-Latour, then Manet and Degas, that propelled Berthe into a full-fledged career as a painter. Berthe Morisot’s correspondence is the best portrait of her circle of friends. Manet occupies an important place in it and multiplies her portraits. Morisot married Eugène Manet, one of the artist’s brothers, in 1874, the year in which the Impressionist adventure, of which she was a protagonist, began. In the seventh section, Aux courses, we enter the world of hippodromes: the rise of horse racing from England joined the aspirations of Parisian modernity in the 1860s: social brilliance, interest in money, sporting competition, experience of speed. All the images in the print repeat the same scenes and effects: flying gallops and agitated crowds. Rather than the ride, Degas depicts the moment before the start, the dancing of the mounts, the bright thrill on their robes, emphasizing the slenderness of the legs.

With the eighth section(D’une guerre à l’autre), the theme of war is explored: Manet, a staunch republican, often exhibits works related to events that affect or revolt him, such as the civil war or the execution of Emperor Maximilian in Mexico. He wants to affect public opinion, while Degas always excludes the chronicle from his public work. Requirements during the Franco-Prussian War, the two painters had to defend besieged Paris in 1871. The two artists ondivided long weeks of waiting, cold and deprivation. In 1872 Degas visited for the first time his family who lived off the cotton trade in New Orleans. He evoked Manet several times that “he would see beautiful things here” and discovered a society still marked by slavery.

With the ninth section(Impressionnismes) we finally enter the history of Impressionism, full of amusing crossovers: Manet moves away from the dissident movement, although his painting seems to evolve toward greater clarity and vivacity. In contrast, Degas takes the lead in the group without conforming his painting to the aesthetics of Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. However, Degas and Manet do not ignore the thrust of an “open landscape” based on unity of motif and mobility of perception. Seascapes and beach scenes preserve them around 1870. “Making an impression” seems to Manet a necessity, but like Degas, he forges a separate Impressionism. The tenth section, Réseaux croisés, shovels in the literary frequentations of the two artists. A learned and literary painter, Manet frequented Charles Baudelaire, Émile Zola, and Stéphane Mallarmé, and portrayed them. The more he claimed independence from institutions, the more he had to connect with intermediaries in the art market and the press to obtain publicity mediations. Does he not intend to exhibit at the Salon until his death, under all regimes and all juries? Degas showed less of his literary tastes and connections before 1870. To thank them for their support, he delivered biting portraits of art critics Edmond Duranty or Diego Martelli.

Paris is featured in the 11th edition, Parisiennes. Manet and Degas are very attached to Paris. Through the figures of the Parisiennes a close dialogue is established between the two artists, whose subjects and approach echo the naturalist novels of the Goncourt brothers or Zola. In the “New Painting” of Manet and Degas, the depiction of women from different social categories, evocative of modern life, plays a decisive role. Around similar subjects, they try to infuse their works, posed and executed in the studio, with the spontaneity of scenes taken from life. The twelfth section, Masculin-féminin, is about the two artists’ relationships with women. Described as a seducer, Manet is never as comfortable as he is in female company. In contrast, Degas’s life “was always emotionally mysterious.” These differences in temperament are partly reflected in their works: while Manet depicts women whose pose and gaze convey confidence, the relationships between men and women in Degas seem almost always troubled or unbalanced.

The nude is the protagonist of the thirteenth section(Du nu). Since the Renaissance and the reappropriation of the Greco-Roman heritage, the nude has played a central role in learning the arts of drawing. The so-called “classical” theory made the idealized, more or less sensual body the canon of its aesthetics and teaching. To challenge this principle was to overturn an entire order of values. Romantics, like Delacroix, and realists, like Courbet, worked on this in the early nineteenth century, before photography and the New Painting dissolved the canons of beauty. From Olympia to Degas’s “Bathers in the Bedroom,” female nudity displays a truth as compelling as it is disturbing. The last section is titled Après Manet: struck by Manet’s death in 1883, Degas is said to have declared at his funeral, “He was greater than we thought.” Degas then participated in initiatives to bring the art community together, including the banquet organized in Manet’s honor in 1885, then the subscription launched by Monet in 1890 to bring Olympia to the Louvre Museum. His admiration for Degas is most evident through his collection of artworks that he planned to make into a museum. He describes in his writings how he managed to collect nearly 80 works by Manet between 1881 and 1897: donations, purchases or even exchanges for his own works.

For all information about the exhibition you can visit the Musée d’Orsay website.

|

| At the Musée d'Orsay, a major exhibition compares Manet and Degas |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.