At Mudec an exhibition on African presences in art between the 16th and 19th centuries

From May 13 to September 18, 2022, Mudec - Museo delle Culture in Milan is hosting the anthropological exhibition La Voce delle Ombre. African Presences in the Art of Northern Italy, one of the first exhibitions in Italy on the subject. The exhibition, curated by Mudec’s scientific staff, investigates the modes of artistic representation of men and women originating from the African continent in northern Italy between the 16th and 19th centuries, and is part of the broader research project begun with the remounting of the museum’s permanent collection. The exhibition takes the form of an initial attempt to identify different ways of depicting the other, revealing canons and clichés of this type of image and trying to restore an identity to these figures through the recovery of their human stories and the role they played in the society of the time. Through the exhibition of works of different kinds from important public and private institutions, it will thus be possible to reflect on the perception and representation of otherness, distinguishing historical figures from mythical ones, stereotypes from real people.

By juxtaposing the documentary evidence, also consisting of the works themselves in the exhibition, with the studies of the scientific committee (amply documented in the catalog published by Silvana Editoriale), it was possible to understand the variability of the occasions on which people of African descent arrived in Northern Italy - mostly through the Mediterranean trade - and with purposes - mostly of domestic servitude - also linked to extra-economic reasons and social prestige. The exhibition is located in the museum’s Focus Rooms and unfolds in sections, focusing on the different ways in which black people are represented. The layout, curated by Origoni Steiner Studio, is configured through a black/white chromatic dualism and minimal graphic elements, which help to emphasize the weight of black figures within each work, accompanying the visitor in reading the works on display.

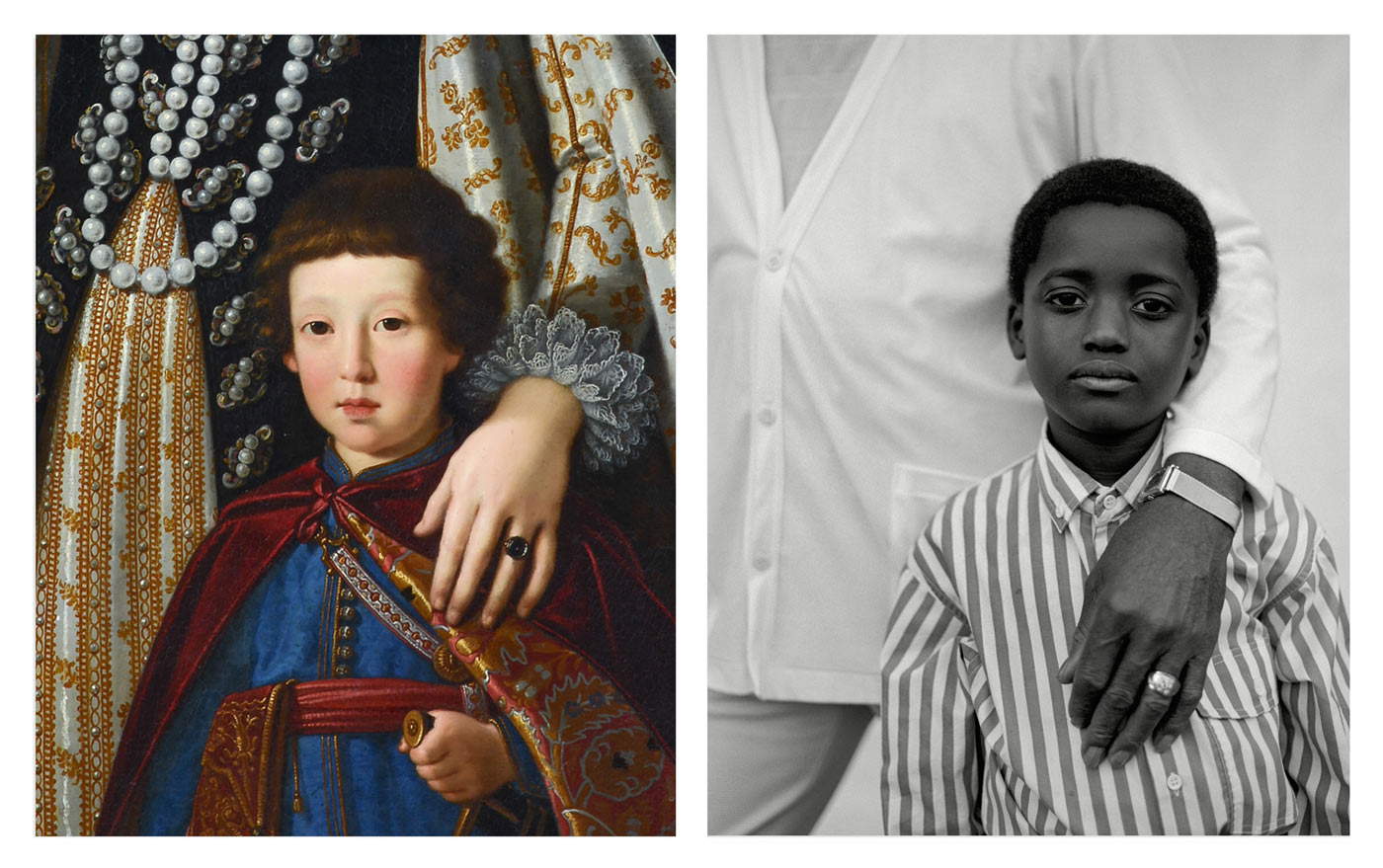

The exhibition opens with a document from the Archives of the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo, which attests to the purchase of a four-year-old black slave, Dionisio, by the nobleman Gaspare Ambrogio Visconti in 1486. It is the text itself, with its intrinsic elements, that gives the audience an understanding of how slavery, although present in the Milanese territory, was not so widespread at that time. The introductory section, Introduction. Giving Voice to the Shadows, focuses on the goals of the review. Born from the research for the remounting of the museum’s permanent collection, the exhibition aims to add a piece to the contemporary debate on the representation of African people in northern Italy and on slavery: a historical and iconographic theme that until now has been little frequented, especially in our country, despite the large presence of works such as those on display in art collections even only in Lombardy. From the sources we understand the variability of the occasions on which people of African descent arrived in northern Italy. The ’route’ was mainly the Mediterranean trade, a phenomenon well spread since the 13th century and providing the ’model’ for the Atlantic trade; the fate, mostly to serve in noble houses (as opposed to the wearing jobs in other parts of Italy and the world). However, we also find people who managed to free themselves from slavery and achieve special status or economic independence, especially if they converted to Christianity. The exhibition aims to be a stimulus to investigate the phenomenon in depth and understand what the identity of these people was. Having arrived in Italy, often renamed with Italian names that concealed their origin, they disappeared from archival documents only to reappear in paintings: sometimes as protagonists of legendary iconographies, sometimes as voiceless shadows next to their lords, and finally as people in the flesh. These testimonies were juxtaposed with the works of Theophilus Imani, a Ghanaian-born Italian visual researcher who, through his diptychs, juxtaposes details of ancient paintings with contemporary photographic works, providing through contrast a different perspective on historical images. His work, along with that on the sources of researchers whose contributions are collected in the exhibition catalog, highlights stereotypes by putting people back at the center.

The first section, Shadows without a Voice, explores the theme of the presence of women and men from the African continent in sixteenth-century Europe and Italy, which is due to the increased mobility between different areas of the world. The slave trade from Africa is not limited to the prevalent Atlantic trade or deportation to the Americas, but also takes place albeit in smaller numbers through the Mediterranean routes. Many men, mostly of North African and Turkish origin, are then captured during military clashes between Christians and Ottomans. In the Italian regions they are mainly exploited as agricultural laborers, rowers on galleys, and as servants in the homes of nobles and upper middle class people: in Lombardy and the northern regions lacking ports and latifundia, the latter is the prevalent destination (even once freed from slavery), resulting in a long series of paintings in which the role of the maid and servant, alongside the portrayed patron, serve to reinforce the latter’s triumphant image. Tiziano Vecellio ’s Ritratto di Laura Dianti con paggio (oil on canvas, 1522-1523) is believed to be the prototype of this composition and was probably the result of an actual copy from life of both figures, since the presence of Africans at the court of Ferrara is well documented, as the Ritratto di Giulia d’Este (Portrait of Giulia d’Este) testifies in the exhibition. Starting in the second half of the 16th century, however, the pairing in painting of lords and servants becomes so widespread that it is difficult to determine whether the depiction of blacks, in portraits of members of the Erba Odescalchi, Clerici, Litta and Arconati families (to name but a few from the Lombard area), indicates their actual existence in those houses or whether instead they are mere compositional inventions of the painter, wanted by patrons to exalt their wealth. In fact, we do not know the identity of any of these people, let alone their stories. Even in a singular case such as that of the young man portrayed twice by Piccio alongside Count Manara (who even dedicated a poem and a sculpture to him), his name remains completely unknown.

In the second section, Legend and Tradition, the audience finds works documenting how numerous figures originating in Africa were included in modern times in paintings to refer to religious or legendary episodes, referable to places far away in space and time, or simply as an element of exoticism. The most famous example is the black wizard king, Balthazar, who in the late Middle Ages assumed the features of an African nobleman as a symbol-along with his Arab and European companions-of the regions of the known world to which Christ’s message was addressed. Before then the three wise men, mentioned only as ’Orientals’ in Matthew’s Gospel, did not in fact have obvious characterizations. Another popular character is Abra, Judith’s maid and her co-star in some masterpieces by Mantegna, Veronese, and Lotto. Compared to the biblical heroine who beheaded Holofernes, Abra does not have an active role but for the artists she is functional in representing the contrasts between complexions (black/white) and age difference (youth/old age). Exotic characters and sometimes bursting sensuality (evident in the Egyptian Sibyl in the exhibition) are found in artistic representations of generic ’blackberry’ and ’Moorish’ figures, frequently approaching cities dominated by opulence, such as the Spanish Milan that became the European capital of luxury production (and where Annibale Fontana’s exceptional cameo is made). Art exploits such images in a propagandistic key and offers an idealized vision of them, bolstered also by the change in the concept of what is beautiful, which from the second half of the 16th century includes the black body. In contrast, in the same decades chroniclers and literary writers describe those subjected to slavery as violent, rebellious and untrustworthy people. Also singular is the view promoted by the prints of Caesar Vecellio’s Habiti antichi, et moderni di tutto il mondo (1598), the first attempt to catalogue a wide range of regional and international customs, but not without racist connotations.

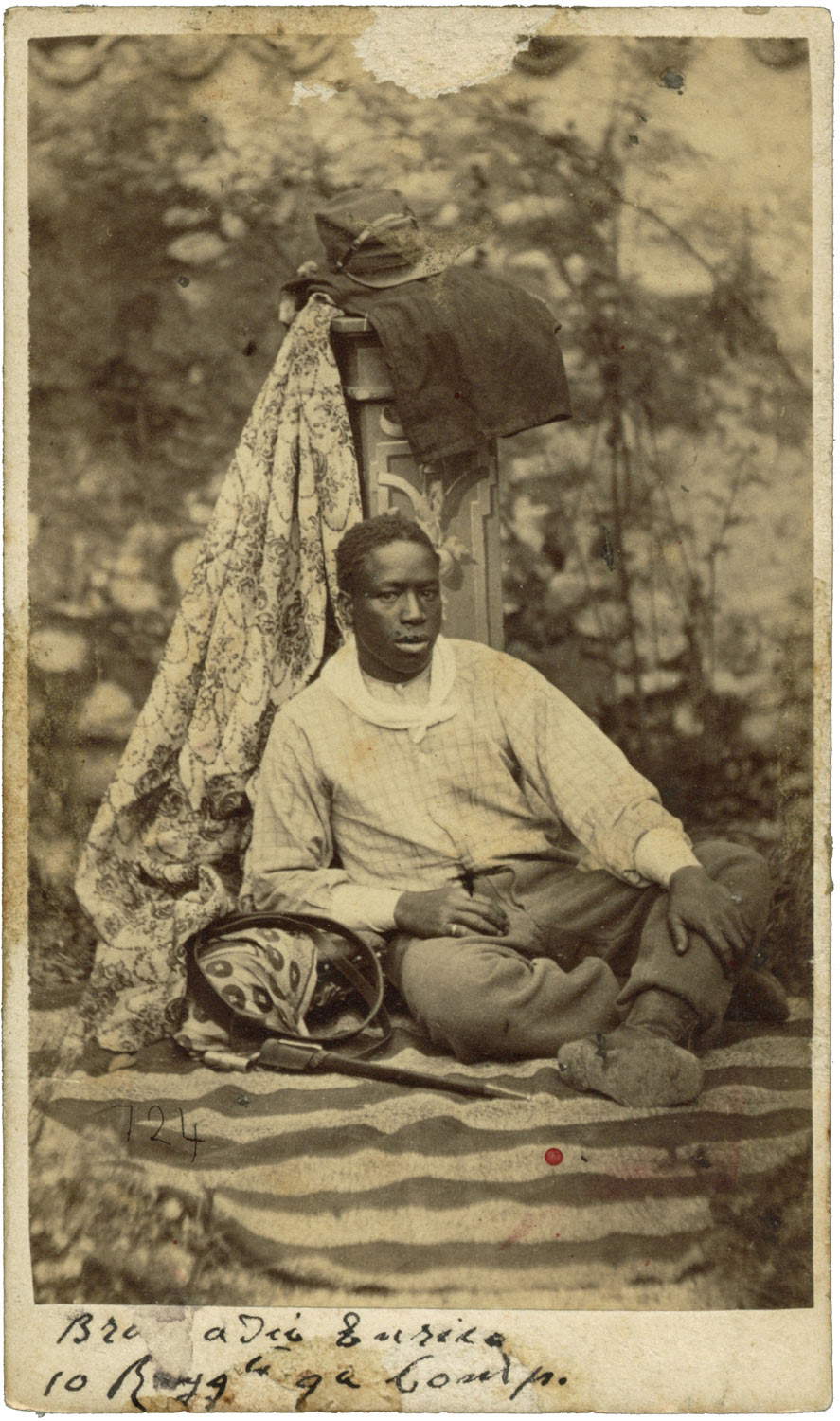

This brings us to the third section, In the Flesh, which deals with the theme of the black body finally taking center stage. In the Venetian school sculptures of the 17th and 18th centuries exhibited here, the iconographic origin of the theme is noble and goes all the way back to the busts of illustrious personages of antiquity; only a thin line divides them from the coeval production of interior decoration, where instead the ’Moors’ were depicted in chains to represent the Christian victory against the infidels. The same variability can be found in coeval painting, where alongside masterpieces such as Ceruti’s The Moorish Beggar (oil on canvas, c. 1730, now in a private Italian collection) are, both on display in the exhibition, the Page with three dogs, a marmot and a monkey, a kind of rebus, and the albino Moor depicted together with an exotic parrot, reminding us that stereotyping remains just around the corner. Among the reasons why a black person earns his place at the center of the representation, religion plays an important role: among the very few to be depicted with the same dignity as whites should be mentioned Muley Xeque, Don Philip of Austria, Infante of Africa and Prince of Morocco, who converted to Christianity and settled in Vigevano, to whom an entire biography is dedicated in 1795. At the same time in Venice, a painting attributed to Francesco Guardi was commissioned for a converted and freed slave, Lazzaro Zen. Fighting for a shared ideal can also help one to become a protagonist: in the 19th century, during the Italian Risorgimento epic, the figure of Andrea Aguyar, a former Uruguayan slave who followed Garibaldi to Italy, rises to prominence; a dual characterization of him is offered in the exhibition: an official portrait and an engraving where humor passes, again and again, through the racist typecasting of the character.

The exhibition closes with a section curated by Theophilus Imani, an Italian visual researcher of Ghanaian origin, who through diptychs taken from his series Echoes and Arrangements highlights the contrasts between Western historical iconography and the representation of the black body in contemporary times. Echoes and Chords is a project of over five hundred diptychs in which classical works and contemporary images of Afrodescendants are juxtaposed. In the series each diptych is a visual rhyme, a correspondence where images are reflected. In this arrangement latent meanings surface, thoughts caught in the moment when the images dialogue. But even before being a dialogue, this reciprocity is a translation; for the eye transmutes one visual text into another, preserving in similarity the effect of difference. “The relationship between European art and Afrodescendant art,” Imani writes, "is not accidental. Echoes and Agreements was born in the middle, from the meeting of two cultural backgrounds: Ghanaian and Italian, African and European. A diasporic terrain where the duality “both/and” embraces seemingly contrasting but essentially similar points of view. A psychic space where people, grasping the meanings that emerge from the dialogue, are propelled not toward what they do not know, but toward what they have not yet thought. Although isolated from the context of the series, the diptychs on display in the exhibition are not orphan thoughts. They are the interweaving of a narrative act that continues, along with other voices not in the room, the path of the black body in the visual history of the country. In their own way, each diptych interrogates, explores and attests to a dimension of the Italian black experience, proposing new keys to interpreting known and lesser-known images. These visual rhymes do not just invite us to see, they invite us to look. And as metaphors they remind us of this: blackness is not empty, it does not live in the shadows; but it unveils itself, in its fullness, to the eye of those who know how to listen."

The exhibition is intended to be a first step in a path of research on a complex topic with multiple social implications. As Mudec Director Marina Pugliese writes, “to give voice to the shadows is to begin to compensate for deficiencies and tend toward an articulation that is as complex as it is necessary both in art historical studies and, more generally, in the collective perception of images.” The exhibition, with free admission, will remain open to the public until Sept. 18. The exhibition catalog is published by Silvana Editoriale. For all information you can visit the Mudec website.

|

| At Mudec an exhibition on African presences in art between the 16th and 19th centuries |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.