An exhibition on the cultural magazines of the early 20th century at the Uffizi

The Uffizi dedicates an exhibition to early 20th century art magazines . Entitled Magazines. Culture in Italy in the Early 1900s, this is a novelty: from June 15 to September 17, 2023, for the first time in an exhibition, the fervent intellectual debate that animated the first decades of the Short Century is fully described, displaying the pages of the avant-garde publications that were its protagonists: among them, Prezzolini’s La Voce, Marinetti’s Futurist sheets, and the socially inspired periodicals of Gobetti and Gramsci. Many figures are made known in the exhibition: Giovanni Papini, Giuseppe Prezzolini, Benedetto Croce, Ardengo Soffici, Tommaso Marinetti; but also Piero Gobetti, Antonio Gramsci, Leo Longanesi, Curzio Malaparte, Massimo Bontempelli and many others. Profound minds, sharp pens, complex, sometimes incendiary personalities, all very different from each other but united by a fundamental characteristic: having (re)animated and made fruitful, with the magazines they themselves founded and directed, the intellectual and political debate of the country in the initial decades of the last century.

Now, for the first time, a museum fully describes and recounts, through the pages of its own protagonists, this restless and fertile period, fervid with ideas, visions, and provocations whose genius and avant-garde scope has withstood the wear and tear of time and continues to bear fruit today.

Organized by the Uffizi together with the National Central Library of Florence (curated by Giovanna Lambroni, Simona Mammana, and Chiara Toti), it offers visitors a comprehensive overview of the most influential cultural publications that appeared on the peninsula during the first quarter of the Short Century: from its beginnings, with the rebellious invectives of Leonardo, signed by Giovanni Papini and Giuseppe Prezzolini, to the pluralist evolution of La Voce, also by Prezzolini, to the act of love for the absolute freedom of ’Art expressed by Ardengo Soffici’s Lacerba, to move, within a little more than a decade, from the futuristic outbursts of Marinetti’s Poetry to a newfound concern for the social with Piero Gobetti(La rivoluzione liberale) and Antonio Gramsci(L’Ordine nuovo). Until branching out, just beyond the threshold of the 1920s, into the “Strapaese” poetics of Leo Longanesi and Mino Maccari(L’Italiano, Il Selvaggio) and the driven internationalism of Curzio Malaparte and Massimo Bontempelli(900). All this always, even in the variety of newspapers and their animators, without ever renouncing the critical gaze, the independent spirit, and that claimed freedom of judgment that, in every age, is an indispensable characteristic of great intellectuals.

More than 250 pieces make up the exhibition itinerary: not only the original editions of the magazines, but also books, posters, sheets, covers, caricatures and a careful selection of paintings, drawings and sculptures of the time.

The exhibition itinerary

1903 marked the beginning of the great Florentine season of magazines, opened by Giovanni Papini and Giuseppe Prezzolini’s Leonardo (1903-1907), which brought together young intellectuals united by antipositivist idealism and moved by the desire for a disruption of the culture of the time. Also in Florence was born Il Regno (1903-1906), founded by Enrico Corradini, the first important press organ of Italian nationalism. Last comes Hermes (1904-1906), a D’Annunzio-inspired literary magazine. In the same fruitful 1903, the first issue of Benedetto Croce’s La Critica (1903-1944) came out in Naples, with the intention of carrying out a critical activity guaranteed by the authoritative presence of Croce and Giovanni Gentile.

Having overcome the restless phase of Leonardo, Giuseppe Prezzolini founded La Voce (1908-1916) in Florence, a magazine destined to play a central role in Italian cultural and political debate. Thanks to the contribution of a large number of contributors from different backgrounds, it established itself as a fundamental organ for the circulation of ideas, in a context of guaranteed pluralism and international scope. Through its columns, where the signatures of Giovanni Amendola, Benedetto Croce, Gaetano Salvemini, Giovanni Gentile and most of the intellectuals of the time parade, the new Italy is outlined and a fundamental work of dissemination of French art, from Impressionism to Cubism, is also carried out. This experience would later result in such distinguished publications as L’Unità and Lacerba. From 1915 to 1916 La Voce split into two literary and political magazines, directed respectively by Giuseppe De Robertis and Antonio De Viti De Marco.

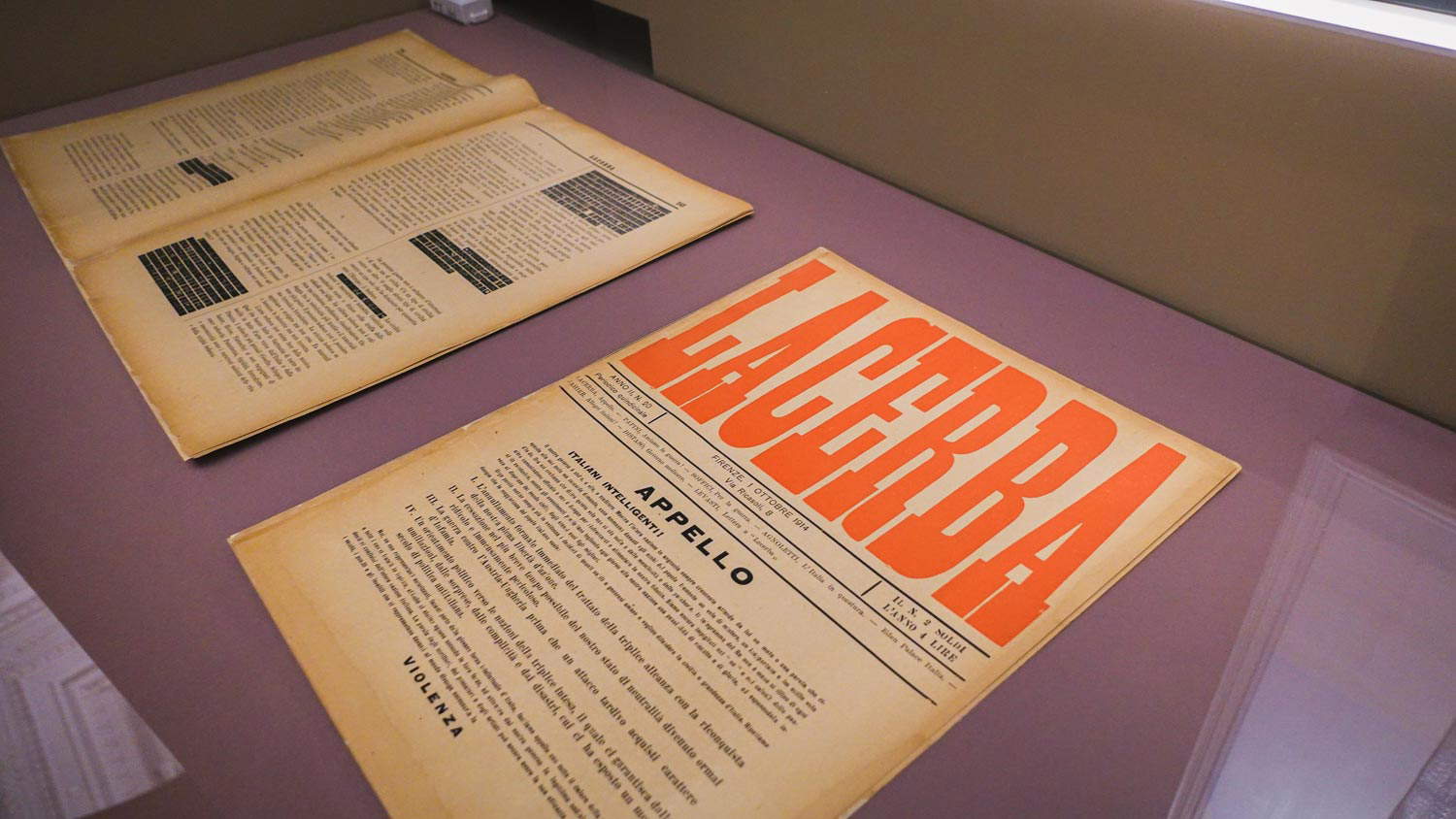

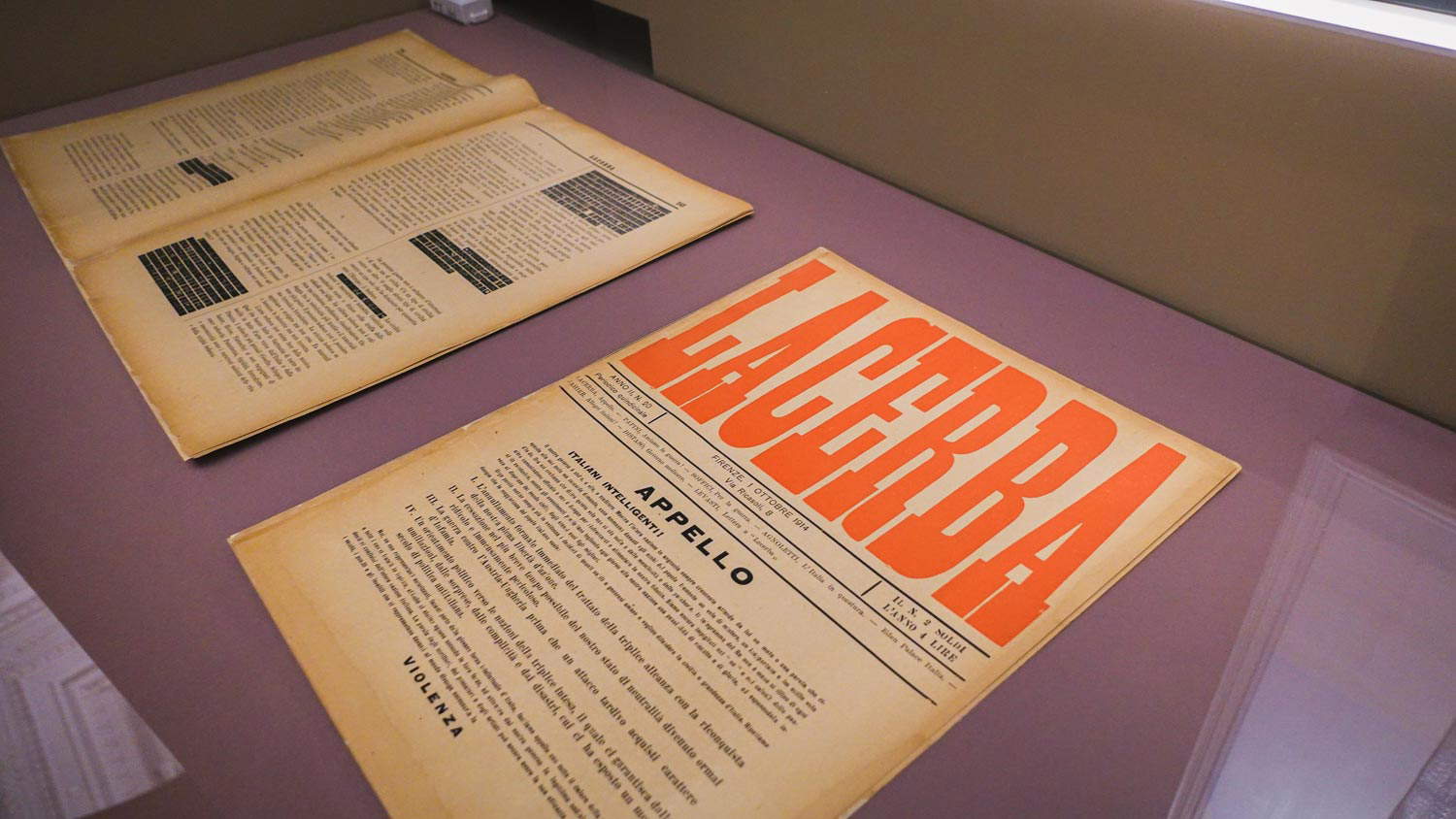

In 1913 Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici, with the collaboration of Aldo Palazzeschi and Italo Tavolato, founded Lacerba (1913-1915). Leonardo ’s heroic accents and scornful tones are recovered, to which is added the Tuscan taste for sarcastic mockery. A protagonist of the Florentine season of Futurism and its memorable soirees, the Lacerba group organized Futurist exhibitions between 1913 and 1914 that brought the works of Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini to Florence. The magazine offered critical contributions on Cubism, Papini’s speeches against passatism, Palazzeschi’s humor-laden writings, as well as verse by Giuseppe Ungaretti and Dino Campana, as well as programmatic manifestos and parolibere tables. After an outspoken interventionist campaign, it will cease publication to coincide with Italy’s entry into the war.

Poesia (1905-1909) is founded in Milan in 1905 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Sem Benelli and Vitaliano Ponti. In addition to promoting the works of Giovanni Pascoli, Giosuè Carducci and Gabriele d’Annunzio alongside those of Gustave Kahn, John Keats and William Butler Yeats, it publishes the Manifesto of Futurism in 1909, becoming the organ of the movement. Instead, L’Italia Futurista (1916-1918) was born in Florence, founded and directed by Emilio Settimelli and Bruno Corra later also with Arnaldo Ginna. Ample space is devoted to the writings of Marinetti, who, together with Balla, also participated with the Florentine group in the making of the film Vita Futurista.

The dramatic experience of World War I highlights a renewed need for certainty, for a "return to order." It was in this climate that Valori plastici (1918-1921) and La Ronda (1919-1923) were born in Rome. Valori plastici is characterized by a strong link with metaphysical painting, promoting the dissemination of the aesthetic theories of Carlo Carrà, Giorgio de Chirico and Alberto Savinio, oriented toward a return to pictorial classicism and the exaltation of Italian figurative culture of the 14th and 15th centuries. Similarly, La Ronda, invokes the idea of a “comeback” within the ranks of the literary world: in polemic with the literary avant-garde, it advocates a return to a classicism based on the literary fathers of nineteenth-century Italy, Manzoni and Leopardi.

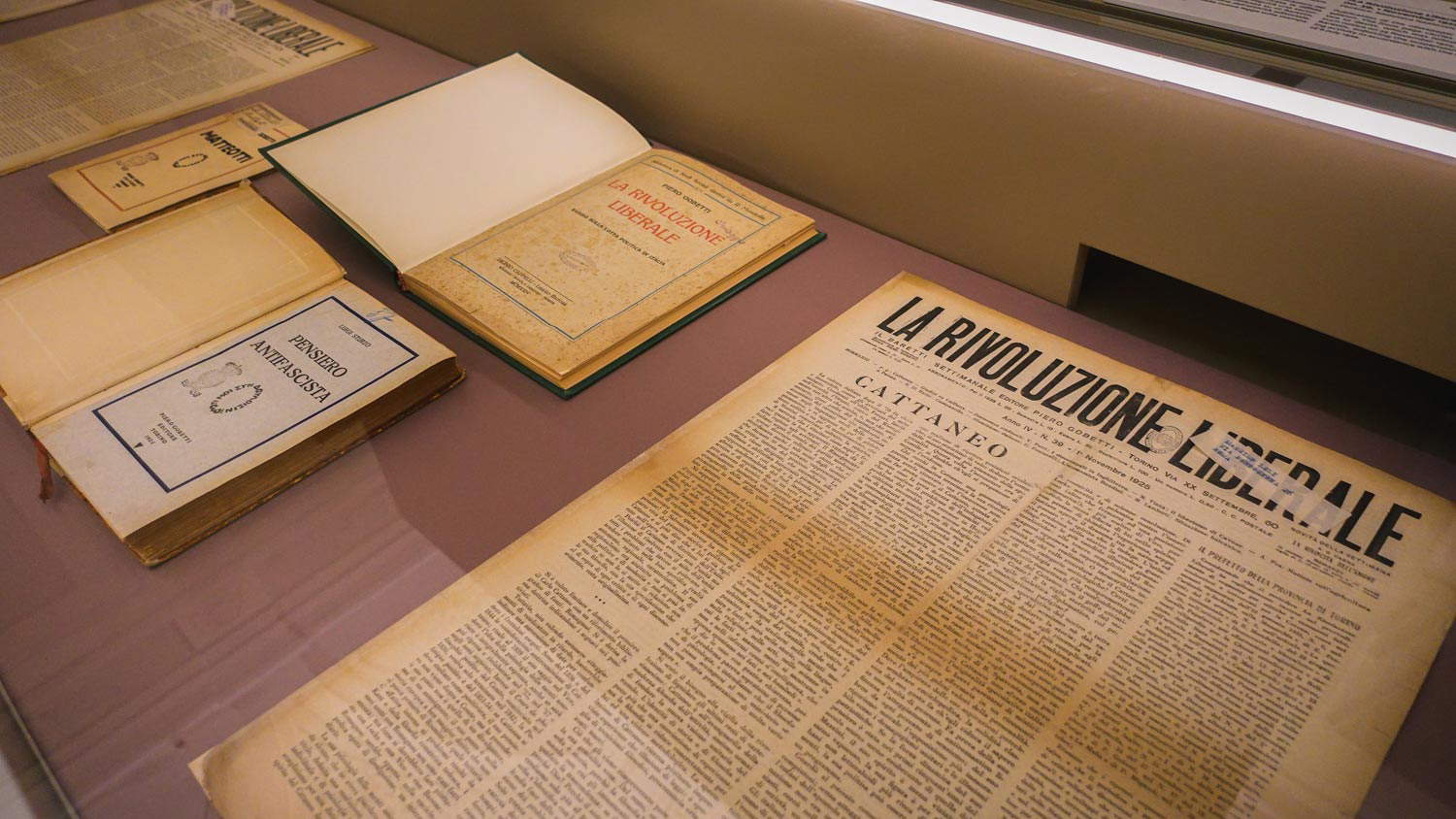

In the Turin of the immediate postwar period, the figure of Piero Gobetti emerged, who, at only seventeen years old, founded Energie Nove (1918-1920). His focus on political and social issues brought him close to Antonio Gramsci, founder with Angelo Tasca, Umberto Terracini and Palmiro Togliatti of L’Ordine Nuovo (1919-1922), organ of the fledgling factory council movement. With Rivoluzione Liberale (1922-1925) Gobetti resumed the political path taken by Energie Nove, investigating the historical causes of Italy’s innumerable contradictions. Following the Matteotti crime, restrictions on freedom of the press made it impossible for Gobetti to continue the publication of his political writings: hence the birth of precisely the last of his journals, Il Baretti, whose purely literary character allowed him to pursue opposition to fascism on a cultural level.

With the rise of Fascism, a cultural tendency opposed to foreignophilia and cosmopolitanism asserts itself in Italy: it is the Strapaese and supports the idea of an autarkic culture, of an art of country inspiration that serves to orient political action and restore to gentrified Fascism its true nature. Strongholds of this trend are the magazines Il Selvaggio (1924-1943) and L’Italiano (1926-1942). They were born far from the capital: the first, in Colle Val d’Elsa, later moving to Florence under the leadership of Mino Maccari; the second, in the heart of Bologna, where it was founded and directed by Leo Longanesi, who in the 1930s would find himself heading them both. Both soon abandoned their original political slant to make room for purely artistic and literary themes, while reaffirming the right to be able to laugh at anyone, including the powerful.

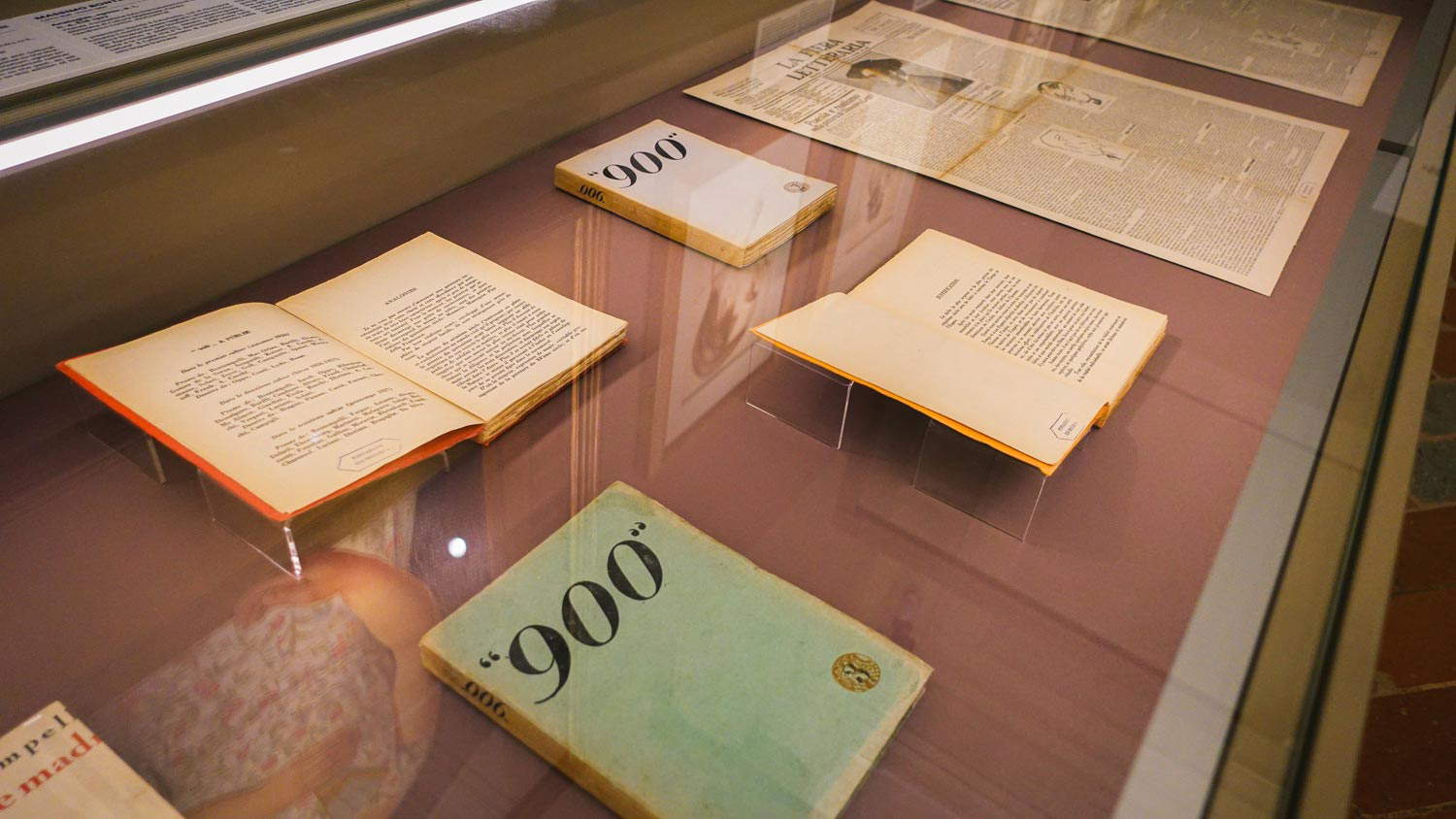

In the same years in which the Strapaese titles were advocating autarkic closure, two magazines were born on the opposite side that preached openness to new European-style currents: 900 (1926-1929) and Solaria (1926-1934). 900 was born from the desire of its founders, Massimo Bontempelli and Curzio Malaparte, to give birth to an international publishing reality (the choice to publish in French is emblematic). Alberto Carocci’s Solaria shares the Europeanist mission, but within it are divided on one side the “rondisti,” who aspire to an art far from political involvement, and on the other side the “solarians,” who see culture as an instrument of analysis and denunciation. The critical, independent and cosmopolitan spirit of both magazines ill-suited the growing intransigence of the regime: “900,” following the imposition of the use of Italian, closed its doors after a few years; Solaria, despite countless interferences and censorships, survived until the mid-1930s.

Statements

“The cultural avant-gardes of the early 20th century, which had Florence as their epicenter, constituted a moment of great originality and fervor for Italian culture, which became more and more European,” says Culture Minister Gennaro Sangiuliano. "I am honored to accompany the President of the Senate, Ignazio La Russa, to the opening of a valuable exhibition, which has the merit of recalling that melting pot of intelligences that were the Italian journals in the early 20th century. The sharpest and brightest minds in national politics and culture confronted each other in the pages of influential periodicals, from the beginnings of Leonardo by Papini and Prezzolini to 900 by Bontempelli and Malaparte and Solaria by Carocci, the last to express a voice of freedom at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s. The ideas born out of this even bitter, but still lively and fruitful confrontation have long nourished Italian political and philosophical thought, sometimes reaching the present day. After years of silence with this exhibition we return to discuss idealism and the response to positivism."

“This exhibition,” stresses Paola Passarelli, director general of Libraries and Copyright, “constitutes a further opportunity to learn about and enhance the extremely rich heritage of periodicals (magazines, newspapers and single issues) owned by the National Central Library of Florence, a collection without equal in our country. The more than 160,000 titles, in some cases preserved in single copy, for about 3,400,000 physical volumes, just under 6,000 current titles, are tangible evidence of its role as a ’national book archive’ - a locution, this one, referring to the entire complex of bibliographic heritage protected by the Institute by reason of the legislation on ’legal deposit’ since the Unification of Italy. The project underlying the exhibition enhances in an original way the documentary and iconographic resources of two fundamental Italian cultural institutions, in a fruitful dialogue that gives rise to a virtuous synergy between different but complementary worlds, professionalism and heritages.”

“The exhibition,” explains Uffizi director Eike Schmidt, “constitutes an absolute first, in terms of breadth and content: the magazines, the cover graphics, the works of art by great artists of the time, together with the texts-many of them of extraordinary quality and commitment-immediately make us enter a world of fervent and fruitful exchanges among the intellectuals of the time, some of them very young. It’s like watching the historical film of those decades in the early twentieth century that changed the face of Italy and its position in relation to Europe.”

|

| An exhibition on the cultural magazines of the early 20th century at the Uffizi |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.