An exhibition on monstrous faces and caricatures in Venice. Autograph drawings by Leonardo also on display

From January 28 to April 27, 2023 Palazzo Loredan - Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti hosts the exhibition De’ visi monruosi e caricature. From Leonardo da Vinci to Bacon, curated by Pietro C. Marani together with a scientific committee composed of Alessia Alberti, Luca Massimo Barbero, Paola Cordera, Inti Ligabue, Enrico Lucchese, Alice Martin, Alberto Rocca, and Calvin Winner.

The aim of the exhibition is not so much to investigate how and why the singular genre of caricature, or rather of the deformation and transformation of physiognomic features, developed, as to make evident the existence of a “northern” line of continuity in this sphere that, starting from Leonardo’s “monstrous faces” and the “ridiculous paintings” of the Lombards, assumed the experiences of Carracci’s naturalism, would flourish in the lagoon in the first half of the eighteenth century.

“De’ visi monruosi non parlo, perché senza fatica si tengono a mente,” so we read among Leonardo da Vinci ’s annotations in the Codex Atlanticus and the Treatise on Painting. At the exhibition sponsored by the Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation, visitors will see the many “loaded heads” or “grotesques,” deformed faces, exaggerated or caricatured figures created by the great artists active in northern Italy between the 16th and 18th centuries.

More than 75 works on loan from international museums and private collections, from the Musée du Louvre in Paris to the Civiche Raccolte d’Arte of Castello Sforzesco, from the Uffizi Galleries to the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden, from the Designmuseum Danmark to the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice to the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, will be on display. Also present is a nucleus of seventeen Leonardo’s autograph drawings, including the well-known Testa di Vecchia in the Ligabue Collection, lent exceptionally by the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the Pinacoteca di Brera and, for the first time in Italy, the Devonshire Collections in Chatsworth.

The exhibition route starts with Leonardo da Vinci and reaches the Venice of Anton Maria Zanetti and the Tiepolos, passing through Francesco Melzi, Paolo Lomazzo, Aurelio Luini, Donato Creti, Arcimboldo, as well as Carracci and Parmigianino. That of the alteration or deformation of physiognomy, which in the twentieth century takes on new meanings, is a theme evoked in Francis Bacon ’s masterpiece entitled Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne, displayed in closing.

“This exhibition also prompts us to reflect on our humanity,” says Inti Ligabue, president of the Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation. “In a way that is certainly ’different’ from what we have done in past years with exhibitions with an archaeological, anthropological and ethnographic slant dedicated to distant cultures and civilizations, but always open to the knowledge and understanding of society, its values, and its cultural expressions. It is Man at the center of our interests; Venice is the starting and returning point of our explorations and research, and desire to discover and share is the driving force of our Foundation.”

To get to caricature, which spread in the 18th century in the lagoon intertwining with the great Venetian musical and theatrical tradition, the exhibition at Palazzo Loredan starts with Leonardo da Vinci. While Leonardo’s drawings cannot be called caricature, that is, directed at mockery, irony or smiling, his “loaded heads,” the exasperation of somatic features, the physiognomic studies of human characters and “mental motions,” the strenuous analysis of deformation to remark a will of realism, but also moral qualities or special virtues beyond physical defects or signs of the times cannot but have influenced and inspired these eighteenth-century outcomes.

One thinks of the immediate fortune of his studies, of the many imitators and followers active in the lagoon such as Giovanni Agostino da Lodi or Giovan Paolo Lomazzo, of the reproductions in the following centuries (among all the seventeenth-century prints by the Bohemian engraver Wenceslaus Hollar, who offers in size 1:1 drawings belonging to the collection of the XXI Earl of Arundel) and especially to the Leonardesque revival witnessed in Venice in the first decades of the 18th century by major artists and collectors such as Anton Maria Zanetti, the progenitor of Venetian caricature, and the nobleman Zaccaria Sagredo.

The note on Zanetti that appears in the manuscript pages preceding theCini Album, some important sheets of which are on display, marks for curator Pietro Marani the track to follow in order to innovatively propose a Tuscan-Lombard line and properly Leonardesque in the artist’s inspiration, alongside the well-known Emilian training also recalled in the exhibition through the drawings and grotesques of Creti, Carracci (from the Collection of the Duke of Devonshire also the only drawing by Annibale Carracci from the legacy Burlington) and from Parmigianino’s circle. As Marani reminds us, we know of Leonardo’s presence in Venice in the 1500s, a brief but significant one that seems to have influenced Giorgione’s painting and Dürer’s work; we also know of the acclaimed arrival in the lagoon, in 1726 in the collection of Zaccaria Sagredo, of original cartoons by Leonardo from the Casnedi in Milan: an acquisition that Zanetti himself reports in his correspondence; finally, we know that in Venice Paolo Lomazzo, pupil and heir of Leonardo’s manuscripts and guide of the artists gathered in the Accademia della Val di Blenio, must have been several times. It is above all friendships, Parisian and Milanese acquaintances, and the Venetian artist’s rich library that motivate his direct and indirect knowledge of Leonardo’s drawings and the master’s influence on Anton Maria and the artists of the Serenissima. Apart from Zanetti’s connection with the Trivulzio family and the “Zanetti-Carriera clan’s” frequentation with the Milanese milieu and with the patrons of the Clerici family, patrons of Gian Battista Tiepolo, decisive must have been the presence in Venice of Pierre Crozat in 1716 and Pierre Mariette in 1718-1719, with whom Zanetti soon became acquainted. It was they who induced the Venetian to make a trip to Paris in 1720 together with Rosalba Carriera and Antonio Pellegrini, which was then continued in London and Flanders; it was Crozat who possessed for several decades celebrated brush drawings on linen by Leonardo, previously indicated as works by Dürer but recognized by Mariette himself as the master’s autographs; it was Pierre Mariette who acquired a famous Album with copies of Leonardo’s caricatures, at the time believed to be originals, many of them taken from Leonardo’s autograph drawings now held in the Duke of Devonshire’s Collection at Chatsworth, examples of which are on display in the exhibition.

Could it be that none of this was discussed by the two Frenchmen with Zanetti? The question hovers in the exhibition and in the catalog published by Marsilio: is it possible that he did not see and “annotate” such works? If to this, again following the curator’s reasoning, we add that in Zanetti’s library inventory appears precisely a copy of theAlbum Mariette, engraved in 1730 by the Count of Caylus, as well as well as Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting in theeditio princeps, that is, the one printed in Paris by Raphael du Fresne in 1651, but also Lomazzo’sIdea del Tempio della Pittura published in 1590 in Milan, in which he recalls da Vinci’s “monstrous faces,” and his Trattato dell’arte della Pittura, all volumes and editions exhibited on this occasion, then the clues can become evidence.

Visitors may be amused to note how the concise and immediate gesture of certain caricatures by Giambattista Tiepolo, but also those of Zanetti himself, recall what may be considered the only true caricature of Leonardo in existence: that of a “Cleric” in which cunning, wit and mockery are perfectly matched in a few strokes, also exceptionally on display thanks to the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana; and how exaggerated noses, protruding chins, bursting breasts, heads with wigs are of Leonardo’s matrix or at any rate reveal prototypes later taken up and varied by Leonardo’s authors such as Melzi, Battista Franco, Lomazzo, Figino: among them the “caricature of man with conical hat” found in theHomo ridiculo of Lomazzo’s ambit lent by the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, which finds an echo in the works of Brambilla, Figino and Arcimboldo on display in the exhibition.

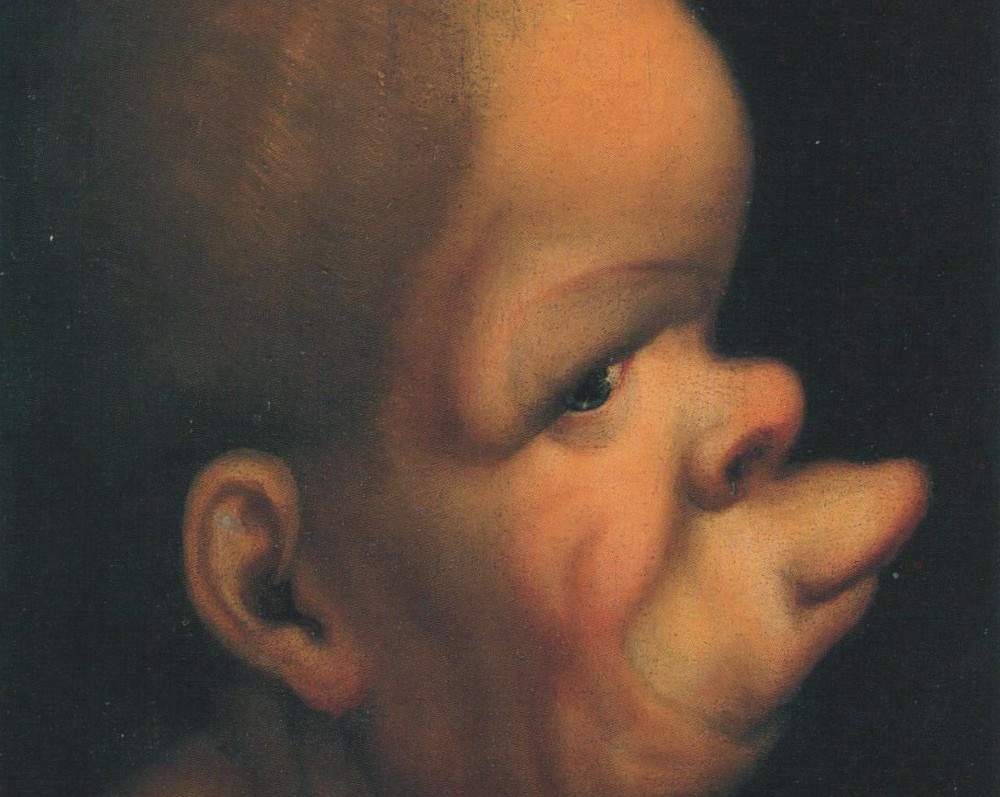

Noteworthy, the oil on canvas with Testa grottesca di donna (1560), attributed to Giovan Paolo Lomazzo already by Longhi, and the gallery of about twenty Tiepolesque caricatures: hunchbacks, prelates and macchiettes of noble lords of different dates, some formerly in the Valmarana Collection and then Wallraf, others from the Terzo tomo de caricature. Lomazzo’s painting, on the other hand, “animalistic and obtuse,” deriving from a very fortunate drawing by Leonardo that was copied and reproduced over and over again, shows the continuation, even in painting, of the path started by the master, where the effects of physiognomic deformation appear even more clearly and seem to corroborate the interpretation of Leonardo’s grotesque heads given by Gombrich (1954), in which the theme of the unconscious and autobiographical depiction would surface.

Environments that foreshadow the psychoanalytic and visionary themes of Francis Bacon ’s painting in his portraits. The exhibition concludes with a triptych by the artist dated 1965: Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne lent by the Sainsbury Centre-University of East Anglia in Norwich. An invitation to reflect on how in the twentieth century this long-standing avenue of art continues by taking on new meanings, leading the study of human nature to the deconstruction, deformation and manipulation of form to manifest interiority and the unconscious.

Image: Giovan Paolo Lomazzo, Grotesque Head of a Woman Turning to the Right, Detail (c. 1560; oil and tempera on panel, 26 x 18 cm; Milan, Private Collection) ©Vivi Papi

|

| An exhibition on monstrous faces and caricatures in Venice. Autograph drawings by Leonardo also on display |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.