An exhibition in Florence celebrates 100 years since the birth of architect Leonardo Ricci

On the occasion of the centenary of the birth of Leonardo Ricci (Rome, 1918 - Venice, 1994), a prominent personality in the Italian post-World War II architectural scene, theformer Refectory of Santa Maria Novella in Florence is hosting the exhibition LEONARDO RICCI 100 until May 26, 2019. Writing, Painting and Architecture: 100 Notes in the Margins of the Anonymous of the 20th Century. Along with archival materials from the CSAC in Parma, works preserved in the architect’s home-studio in Monterinaldi are on display for the first time. Expressionist sketches, paintings of strong material and figurative impact, fragments of mosaic compositions, period photographs and project models are juxtaposed with architectural drawings in a collage that sheds light on aspects of Ricci’s work that have not yet been investigated, through different levels of aesthetic expression. Video/audio documents and magazine excerpts contribute to the comprehensibility of a multifaceted but deeply organic message, masterfully translated by Ricci through the written form as well. The result is a stunning picture of the richness of Leonardo Ricci’s theoretical research, artistic production and design activity as a writer, painter and architect.

The exhibition, curated by Maria Clara Ghia, Ugo Dattilo and Clementina Ricci, aims to present the figure of Leonardo Ricci in a free and asystematic way, with a clear interdisciplinary slant. Guiding the visitor will be excerpts from Anonymous of the Twentieth Century, an existentialist-inspired book written by Ricci in the United States in 1957, “not a learned book for specialists but open to all,” as its author called it. “My desire was to treat some topics closely related to my sphere of activity, which is mainly in the field of urban planning and architecture, but in a non-specific way,” Ricci wrote.

Divided into sixteen “movements,” like the sixteen chapters of the book, the exhibition LEONARDO RICCI 100 offers a path that mixes the plots of the disciplines practiced by Leonardo Ricci, to show their underlying links and interferences. The sections thus mimic the openness of his thought and mix works from different periods and different backgrounds, collecting, rather than cataloging, his production, in which the boundaries between disciplines are lost. The sections thus become possible keys to understanding the man who in Florence had taken Michelucci’s lesson and mixed it with that ofClassical Abstractionism. The man who, in Paris, had frequented Albert Camus, Jean Paul Sartre and Le Corbusier and then had gone as far as North America, where he had become acquainted with the practices ofAction Painting.

A number of works from different disciplines are selected for each chapter, flanked by some particularly significant excerpts from the text. The attribution of the projects to the different chapters is functional for a complex and inclusive reading, which does not follow the principle of list but of open discourse. The tour itinerary is thus not intended to be linear and juxtaposes realizations that are profoundly different in terms of expressive form, era, intended use and scale of intervention, yet close in terms of meaning. This is the same method implemented by Ricci in his writing: themes are juxtaposed or contrasted without following a systematic order but with a process that the author defines as “logical”: not a search for a priori justifications, just the simple and incessant desire to find relationships among the things that exist and establish new ones.

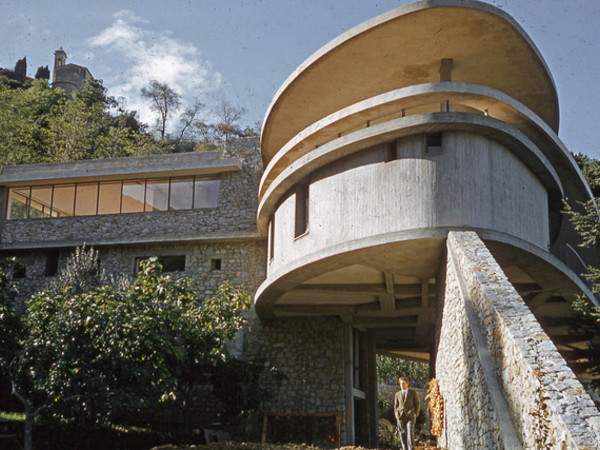

It resembles an agile compendium of the twentieth century, the life of Leonardo Ricci, a man who was able to cross eras, philosophies and nations, and who drew from these the fundamentals to build his own personal vision of the world and practice as an architect. Thus in LEONARDO RICCI 100 we move between the utopian optimism of 1940s postwar Florence, where Ricci participated in competitions for the reconstruction of Florentine bridges, worked with Savioli and Michelucci, and discovered a’love for didactics, moving to existentialist currents that would influence his literary work, until he touched on primitivism and figurativism borrowed from artists such as Schiele and Picasso, but also from contemporaries such as Corrado Cagli and Afro. Ample space is devoted to his manifesto work in Monterinaldi (the Ricci house-studio of 1949, completed in 1961), a work in which the main motifs of his architectural research can be traced. In this very area with Fiamma Vigo, in 1955 Ricci gave birth to La cava, an event in the form of an exhibition manifestation that became famous for its decision to involve the entire hill of Monterinaldi in a collaborative action in which architects, painters and sculptors freely took part, in a complete integration between the arts.

“To make an architecture is to make people live in one way rather than another,” Ricci writes in 20th-century Anonymous, repeating a phrase with which he prodded his students: and it is the question he answers through the villages for Waldensian communities of Agape (1946-47) at Prali in Piedmont and Monte degli Ulivi (1963-67) at Riesi in Sicily, projects in which Ricci fully expresses his community poetics and creative process, or with La Nave, which he made at Sorgane (Florence), a building-city 200 meters long, in which he reveals the designer’s intentions to overcome those critical aspects he traced in Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation.

Also found in the exhibition are the organic-expressionist matrices that characterize the architectures of Villa Mann Borgese in Forte dei Marmi (1957-59), or of the project for the villa Pleydell-Bouverie, for the villa Balmain on theisland of’Elba (1958) and in many other unrealized projects, next to the Italian pavilion for EXPO 67 in Montreal, Canada, where the collaboration with Emilio Vedova and Carlo Scarpa reaffirms his sensibilities once again open to the exploration of areas of 6 artistic expression contiguous to architecture. And again: the Model City project for Florida, the competitions in France, his activity as a tireless teacher: the 100 notes on architecture, painting and architecture return us today a multifaceted portrait of an artist.

Leonardo Ricci’s was an open-ended quest, one that put people’s well-being and bonheur at the center: in Anonymous of the 20th century he wrote “I hope that everyone finds there something of what he seeks, that in this apparently incommunicable world an exchange takes place.” This approach translates into a nonlinear tour itinerary, specially designed by Eutropia Architettura, which juxtaposes profoundly different realizations with a process Ricci calls “logical”: not a search for a priori justifications, just the simple and unceasing desire to find relationships among the things that exist and establish new ones.

The exhibition is organized in collaboration with the City of Florence, DIDA-Department of Architecture of the University of Florence, CSAC-Center for Studies and Archives of Communication of the University of Parma, Fondazione Giovanni Michelucci, and Fondazione Architetti Firenze.

Pictured: Leonardo Ricci, Balmain House (1957-1959 Marciana - Elba Island). Ph credit Ricardo Scofidio

Source: press release

|

| An exhibition in Florence celebrates 100 years since the birth of architect Leonardo Ricci |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.