An exhibition in Carpi on Berengario da Carpi, the Renaissance physician

Scheduled at the Musei di Palazzo Pio in Carpi, from September 14 to December 16, 2018, is the exhibition Berengario da Carpi. The Physician of the Renaissance, all dedicated to the figure of Berengario da Carpi (pseudonym of Jacopo Barigazzi, Carpi, c. 1460 - Ferrara, 1530), a great protagonist of Renaissance medicine, physician to popes and princes such as Lorenzo de’ Medici. The exhibition, curated by Manuela Rossi and Tania Previdi, aims to present this important figure of the time with an itinerary made up of paintings, engravings, drawings, ancient books and manuscripts.

The exhibition in Carpi, through the figure of Berengar, aims to recount a world in which science, art, politics, personal and universal events merged in the men who lived it. In his field of specialization, Jacopo Barigazzi (himself the son of a surgeon, and trained by studying at the University of Bologna, where he graduated in 1489, and at which, moreover, he taught between 1502 and 1527) knew how to modernize and develop a discipline, such as the medico-surgical one, leading it to new horizons of research. During his Bolognese years, when he professed the practice of surgery by perfecting operating techniques, in 1521 Jacopo published Commentaria cum amplissimis additionibus super Anatomia Mundini, the first of three fundamental volumes in the history of ’anatomy and medicine, which made the discipline take a remarkable leap forward in the knowledge and representation of the human body and which, for the first time ever, presented it as it had never been seen, thanks to extraordinary woodcut illustrations, making anyone who leafed through his books discover the image of a heart, the spine, the female reproductive system, the skeleton, muscles, veins and the brain.

Indeed, Berengar’s great insight lay in having understood the value of visual form, of illustration, in anatomy books. This was above all a didactic value, which went hand in hand with a different approach to the study of medicine and anatomy: it was no longer just the rereading of the ancients, but a direct knowledge that passed through the practice of dissections and that had to be “translated,” for students in the first place, but also for artists, as Berengar himself had occasion to affirm.

Between 1522 and 1523, Jacopo Barigazzi published the Isagoge, two editions of a short sylloge of the Commentaria that were immediately a great success and were replicated, while Berengar was still living and until the middle of the eighteenth century, in dozens of subsequent print runs. Having reached the pinnacle of fame, Berengar was sought after by the most important courts of the time, to the point of becoming surgeon to three popes and treating, at the invitation of Pope Clement VII, Giovanni dalle Bande Nere who had been wounded in battle in the leg or Lorenzo de’ Medici who had been hit in the head by an arquebus bullet. Among his best-known recipes is an ointment believed to be prodigious, which, after the addition of mercury, became an effective antisyphilis, but with enormous and lethal side effects.

The exhibition itinerary, divided into three sections, begins with an analysis of the cultural and academic context that between the late fifteenth and mid-sixteenth centuries characterized the Bolognese and Venetian poles, particularly Padua. The rediscovery of ancient classical texts distinguished this period, and the doctors who took turns in the chairs reproposed and commented on, sometimes directly translating, texts fundamental to the study of the art of medicine, hitherto unknown to most. The figure of Berengar, who began to propose corrections of some of the anatomical errors found in the descriptions provided by Galen thanks to the autopsies and dissections he carried out on human bodies, is placed in this context. Presented in this first section are printed volumes such as the Fasciculus medicinae by the German physician Johannes de Khetam, De humanis corporis fabrica by the Flemish anatomist Andrea Vesalio, and the Canon medicinae Avicennae, as well as drawings, woodcuts and surgical instruments of the period.

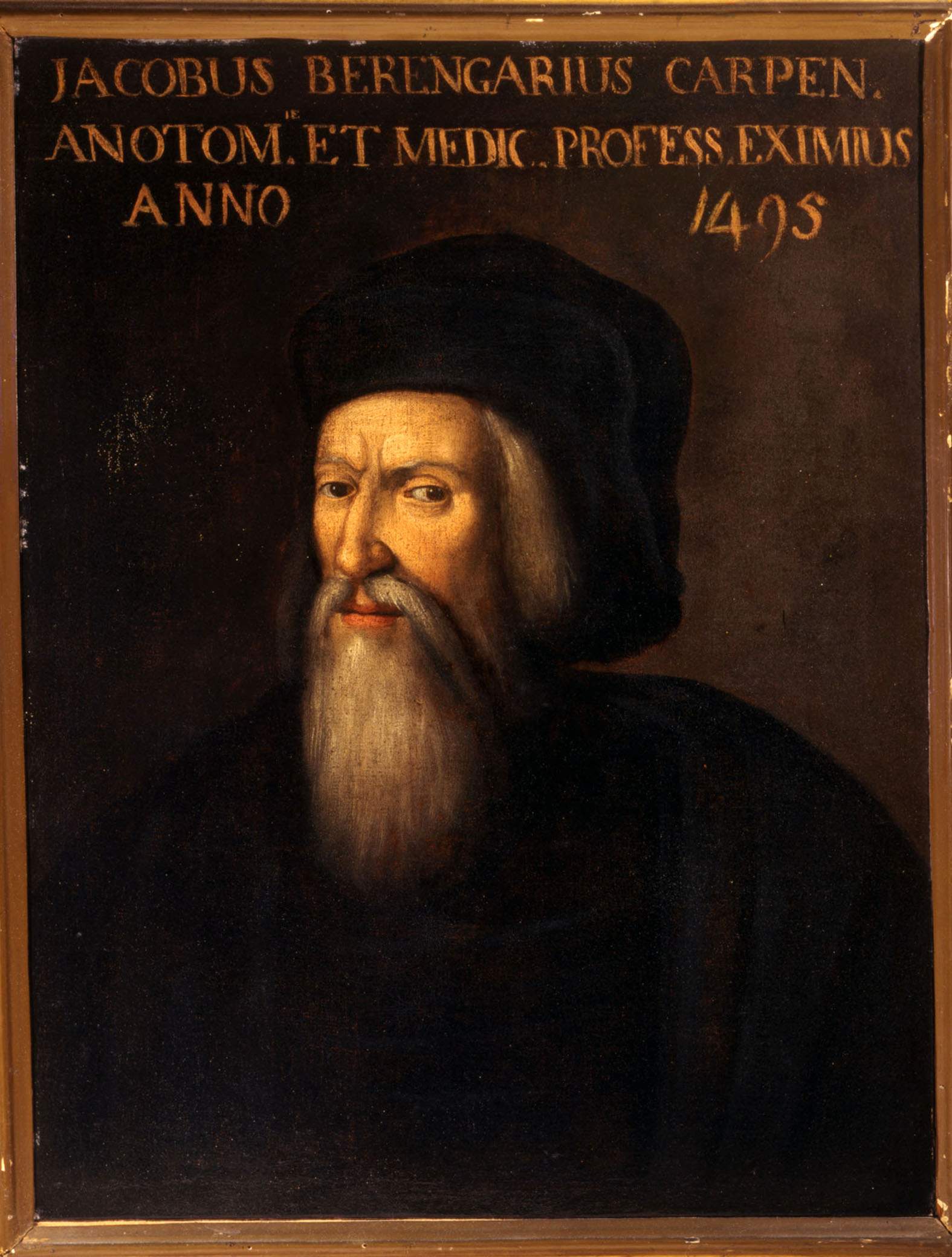

Introduced by Jacopo’s portrait, painted by an anonymous Emilian painter, the exhibition continues with the part, the true fulcrum of the review, in which through documents, volumes, and works of art the figure of Berengario da Carpi is reconstructed in its complexity, bringing out a character who well represents the man of the Italian Renaissance. His connection with the court of the Pio family in Carpi led him to frequent and engage with learned and enlightened figures such as Aldo Manuzio, tutor of Alberto III Pio. The study of Greek and ancient classical texts (volumes from Giorgio Valla’s library, which he had acquired, including numerous medical manuscripts by Galen and Hippocrates, had flowed into the Pio’s library) proceeded hand in hand with the scientific interest of Berengar, who grew up in a family of physicians in which the secrets of effective ointments and plasters were handed down, as did his interest in ’art and ancient history, thanks to which he was able to grasp the beauty and value of the marble fragment of Nero’s bust from the Roman era found underground in Bologna, re-proposed in the exhibition with a holographic installation, created by the Civic Archaeological Museum of Bologna and the engineering department of theUniversity of Bologna, which re-proposes the way Berengar had used to display it in his house, or of the St. John in the Desert painted by Raphael, which belonged to him as a copy, and displayed in the xylographic version, engraved by Ugo da Carpi. In this section, visitors will also be able to admire some precious manuscripts on medical topics from the 15th century, from the library of Alberto Pio, Berengario’s printed volumes, and rare medical reports signed by the Carpi doctor himself.

The exhibition ideally closes with a series of drawings, graphics, and paintings that have as their main subject skeletons, bodies, and human heads, by authors such as Leonardo da Vinci, Antonio Pollaiolo, Domenico Campagnola, Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio, and many others. The illustrations in Berengario’s volumes betray an artist’s hand; in them we recognize iconographic models that refer, in some cases, to ancient sculpture, but more often to iconographies in which the ancient is taken up and adapted to the taste that artists from the Emilian and Lombard area, but also from central Italy, imposed in those years. This is the case of the full-length skeletons, reminiscent of the types depicted in the macabre dances from the second half of the 15th century, where one also encounters that of the “flayed,” engraved, for example, by Marco Dente in the very early years of the 16th century in forms and position similar to the figure in the Commentaria and present in the exhibition.

Visiting hours: Tuesday and Wednesday from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., Thursday through Sunday and holidays from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. Closed Mondays. Tickets: full 8 euros, reduced 5 euros. APM Editions catalog. The exhibition is conceived and produced by the Municipality of Carpi - Musei di Palazzo dei Pio, under the patronage of Alma Mater Studiorum-University of Bologna, the Rizzoli Orthopedic Institute of Bologna, in collaboration with the University of Padua, the MUSME (Museum of Medicine) of Padua, the Civic Archaeological Museum of Bologna, with the contribution of Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Carpi and IGEA Carpi.

Image: Painter of the Emilian school, Portrait of Berengario da Carpi (17th century; oil on canvas, 74 x 54 cm; Carpi, Musei di Palazzo dei Pio)

|

| An exhibition in Carpi on Berengario da Carpi, the Renaissance physician |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.