From Oct. 8 to Nov. 26, 2023, the Bologna Civic Museums of Ancient Art Sector will host the exhibition Guercino and his pupils. From ’heads of character’ to portraits, which aims to explore some specific aspects of the production of Giovanni Francesco Barbieri known as Guercino (Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666) and the rich school of artists who trained with him and his workshop.

The exhibition, set up in the majestic Sala Urbana of the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte, curated by Silvia Battistini and realized thanks to lenders ASP Città di Bologna: Quadreria di Palazzo Rossi Poggi Marsili and UniCredit Art Collection, Quadreria di Palazzo Magnani, represents the inaugural event of the widespread project Itinerari Guerciniani, promoted by the Municipality of Bologna, the Metropolitan City of Bologna, the Municipality of Cento and the Emilia-Romagna Region to mark two happy occasions to highlight the work of the master of Baroque painting, universally recognized and appreciated as one of the greatest exponents of seventeenth-century Bolognese painting: the reopening to the public of the Civica Pinacoteca “Il Guercino” in Cento scheduled for November 2023 following the closure caused by the 2012 earthquake, and the opening of the exhibition Guercino in the studio from October 28, 2023 at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, curated by Barbara Ghelfi and Raffaella Morselli in collaboration with the museum staff.

The exhibition project hosted at the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte is divided into three sections that examine the production of ’character heads’ and portraits, as well as a look at Guercino’s fame. The cue is offered by a number of works preserved there, and in particular by the valuable 17th-century replica of a painting by the Cento-born artist depicting St. John the Baptist in prison tempted by Salome, a rare iconography, but one of which Guercino made six very similar versions. The careful description of Salome’s face, sporting a richly ornamented hairstyle, and the pungent expression of the outraged St. John hark back to the practice of ’character heads.’ Indeed, it was common among artists of the past to start from a study from life of a model, investigate its poses and expressions, until they created a typological face to be used in different kinds of compositions, religious or secular: the so-called ’character head.’

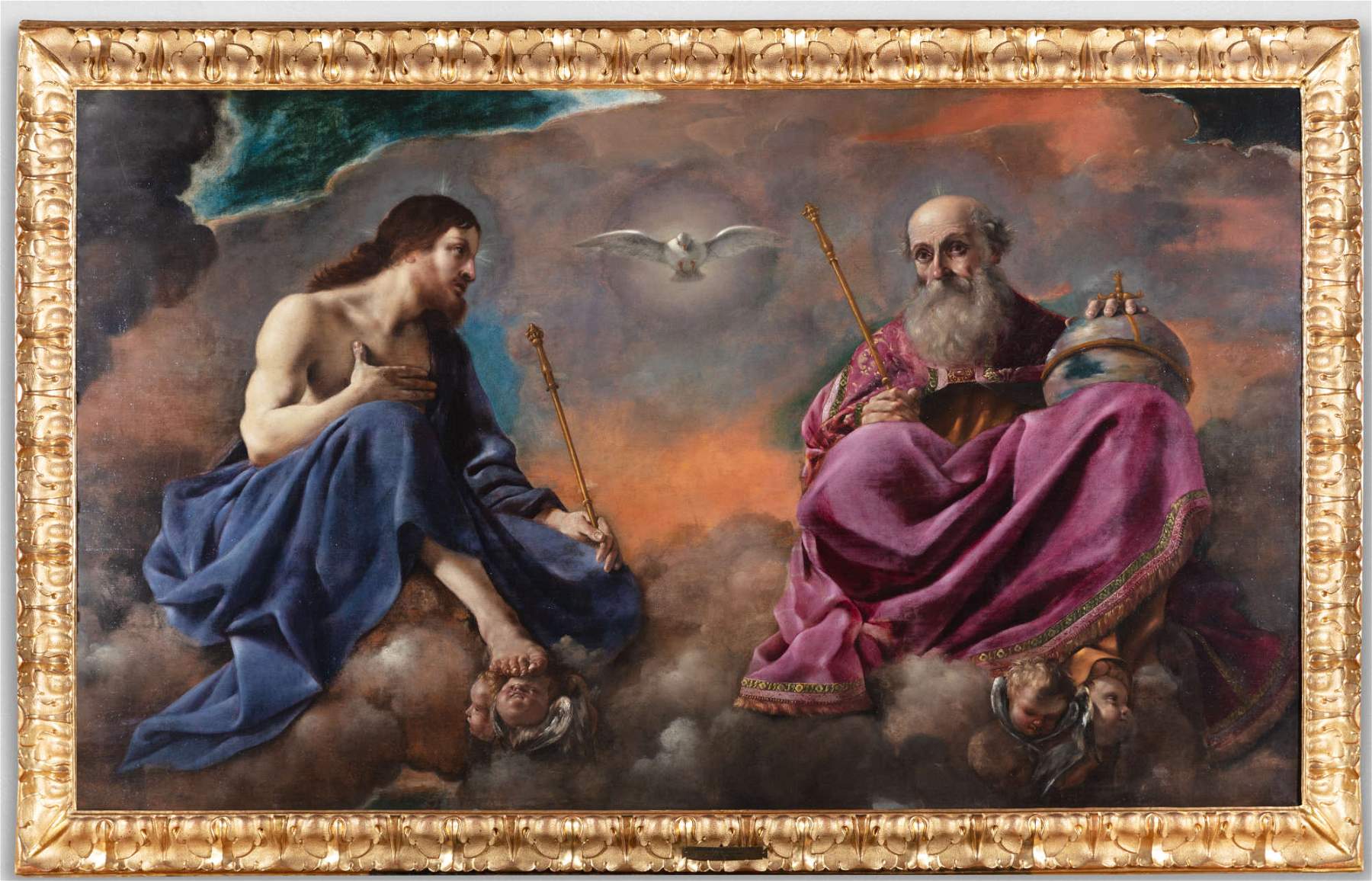

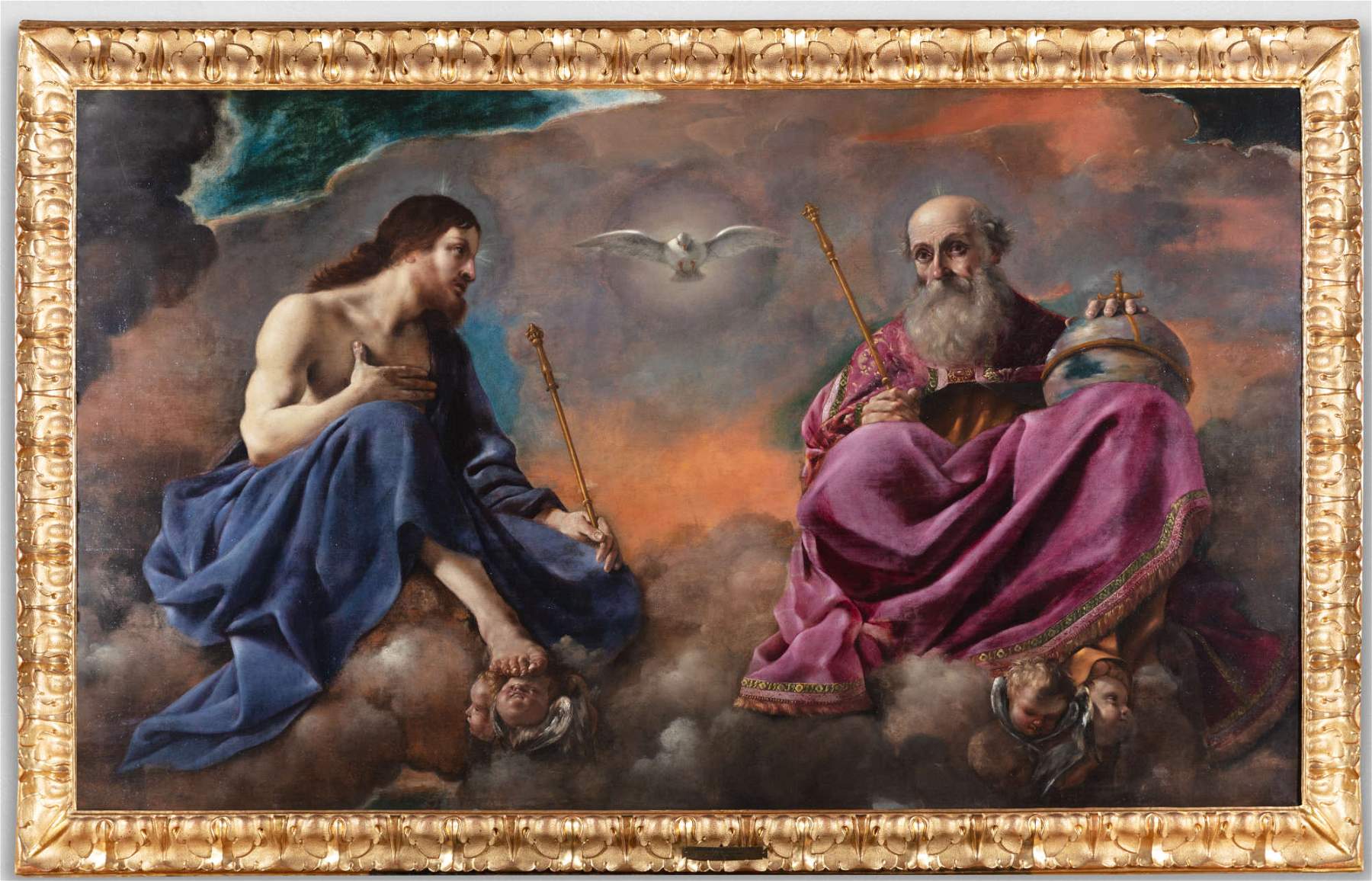

This is the starting point for comparing works by Guercino executed in different periods of his career, in which the subjects have physiognomies so strongly connoted as to present themselves as ’heads of character’: for example, in the valuable autograph works on display in the exhibition, the Trinity (1616, in the image) and Lucretia (c. 1644) owned by the UniCredit Art Collection, Quadreria di Palazzo Magnani in Bologna. The chronological distance of the two paintings documents how Guercino resorted to this method of working throughout his career. In the Trinity, the bold foreshortening of the Eternal Father’s face reveals a study from life, barely diluted by the attribute of the flowing gray beard. In the case of Lucretia, the typification of the face is accentuated by the painting’s conservation episode: it was cut out of a larger painting and stripped of elements that facilitated recognition of the subject. The decontextualized face of the young woman could consequently fit the representation of either a heroine or a saint.

Adding to these works is the display of portraits made by collaborators and pupils of later generations, among whom stood out the brothers Benedetto il Giovane (Cento, 1633 - Bologna, 1715) and Cesare Gennari (Cento, 1637 - Bologna, 1688), grandsons of Guercino, sons of Ercole and Lucia Barbieri, sister of Giovanni Francesco. The portrait genre was much in demand in the past for display in both public and private settings, with the purpose of celebrating or passing on the memory of a family member or illustrious person. Official portraits were usually full-length and almost life-size, painted in a setting that helped define the role of the effigy. More common were half-length portraits, suitable both for paying tribute to ancestors and for remembering loved ones.

This pictorial genre was particularly important for young women, as paintings in which they were portrayed in fashionable ornaments and clothing served to present them in their social environment.

In Cesare Gennari’s Portrait of Dorotea Fiorenza Saccenti (c. 1660) and Benedetto Gennari’s Portrait of a Maiden (c. 1692), the figures are cut off at three-quarter length. This solution hints at the solemnity of the standing pose and the complexity of the dress, but allows the painter to dwell on the gestures and expressiveness of the face.

In addition to a greater naturalism than the ’character heads,’ these fine examples of Baroque portraiture emphasize the gestures of the characters and their placement in a well-defined-and sometimes even minutely described-physical space, which becomes an expression of their social status. The highly detailed depiction of clothing and hairstyles underscores the need to place the subject in a precise temporal space as well, in order to emphasize their specificity.

It was important, however, that the paintings testify to the mild character and accommodating behavior required of maidens at the time; for this they were portrayed with a compact air, without excessive sentimental characterizations and diluting the more specific physiognomic elements through a courtly vision.

That Cesare Gennari did not think it necessary to follow this criterion for men as well is evident in the Portrait of Francesco Maria Dal Sole (1655-1660), in which the view is close up and the dark, neutral background gives maximum emphasis to the young man’s restless, intelligent gaze. The sketchy description of the dress allows the artist to adopt a more rapid and broad brushstroke, in which the effect of three-dimensionality is achieved through mellow chiaroscuro effects.

The beautiful ’talking frames’ in the two portraits painted by Cesare Gennari, from ASP Città di Bologna: La Quadreria di Palazzo Rossi Poggi Marsili, were later made by theOpera Pia dei Poveri Vergognosi and offer an elegant solution to the need to preserve biographical memories of ladies and noblemen to be handed down to future generations. In fact, as time went on, these paintings no longer served to present young scions of the Bolognese nobility, but to celebrate the benefactors they had become: when they died, they had left to the city’s pious works their patrimony to finance charitable activities.

Finally, with three works preserved at the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte, a section is devoted to the fame achieved by Guercino’s paintings, also offering an opportunity to delve into the collecting history of some of the museum’s works and thus testifying to the liveliness of the world of art lovers innineteenth-century Bologna.

The success he achieved already at the beginning of his career conditioned the organization of the activity of his workshop, and soon it became necessary to have well-trained artists who could absorb some of the master’s work. It was in this context that artists were formed who later established themselves with independent production, such as Guido Cagnacci, Matteo Loves, and Benedetto Zalone; some of their works can be seen in rooms 7 and 8 of the Municipal Art Collections. Instead, the role of first aide was filled by those who were able to emulate the master and after 1630 was assigned to Bartolomeo Gennari, author of the San Girolamo penitente from the collection of Agostino Sieri Pepoli.

Guercino’s stylistic evolution prompted his collectors to seek out paintings made at different times in his career. As emerges from correspondence with Prince Antonio Ruffo, the artist himself often worked to track down his early works, seeking them from collectors who were less interested or willing to make exchanges. Unable to accommodate the many requests, he resorted to copies made in-house, faithful to the original in both subject and size. After all, even in the most prestigious picture galleries it was usual to find copies of works that had been successful, which, if of good quality, still testified to the refined taste of the owner.

In other cases, painters of lesser fame painted copies, mostly starting from printed engravings, objects that contributed significantly to ensuring the notoriety of a painting and its author. Such is the case with the Flora from the collection of Pier Ignazio Rusconi, taken from the painting commissioned in 1642 by Giovanni Orio of Rimini and now preserved in Rome ’s Palazzo Rospigliosi. Not only are the measurements very different from the original, but it is evident how the anonymous painter merely copied the subject, letting his own style shine through and showing that he had never seen the work from life.

The small painting with the Vestizione di San Guglielmo, on the other hand, testifies to a different artistic practice: as an exercise and to preserve its exact memory, the Modenese painter Filippo Conventi faithfully copied, but in a smaller format, Guercino’s famous and highly celebrated altarpiece, placed since 1620 in the Bolognese church of San Gregorio e Siro in Bologna.

A brochure containing reproductions of all the works in the exhibition is available for free distribution to the public.

For all information, you can visit the official Cultura Bologna website.

|

| An exhibition in Bologna dedicated to the works of Guercino and his pupils |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.