The largest exhibition ever dedicated toart in Carrara in the early 20th century: it’s Novecento a Carrara. Artistic Adventures between the Two Wars, the exhibition that animates the Tuscan exhibition season from June 24 to October 29 at Palazzo Cucchiari, home of the Giorgio Conti Foundation in Carrara’s historic center. The exhibition, curated by Massimo Bertozzi and organized by the Giorgio Conti Foundation, is an unprecedented project, which starts from a consideration: Carrara has always been associated with sculpture, which has very ancient traditions here, although the first important workshops date back only to the 18th century: that of sculpting marble, however, is a centuries-old habit that has adapted over time to the transformations of expressive languages, and that has always been based on the transmission of techniques and great manual skill. But there is more to Carrara than sculpture: the city, in the early part of the 20th century, was in fact a fruitful artistic hub where many of the greatest painters and sculptors met.

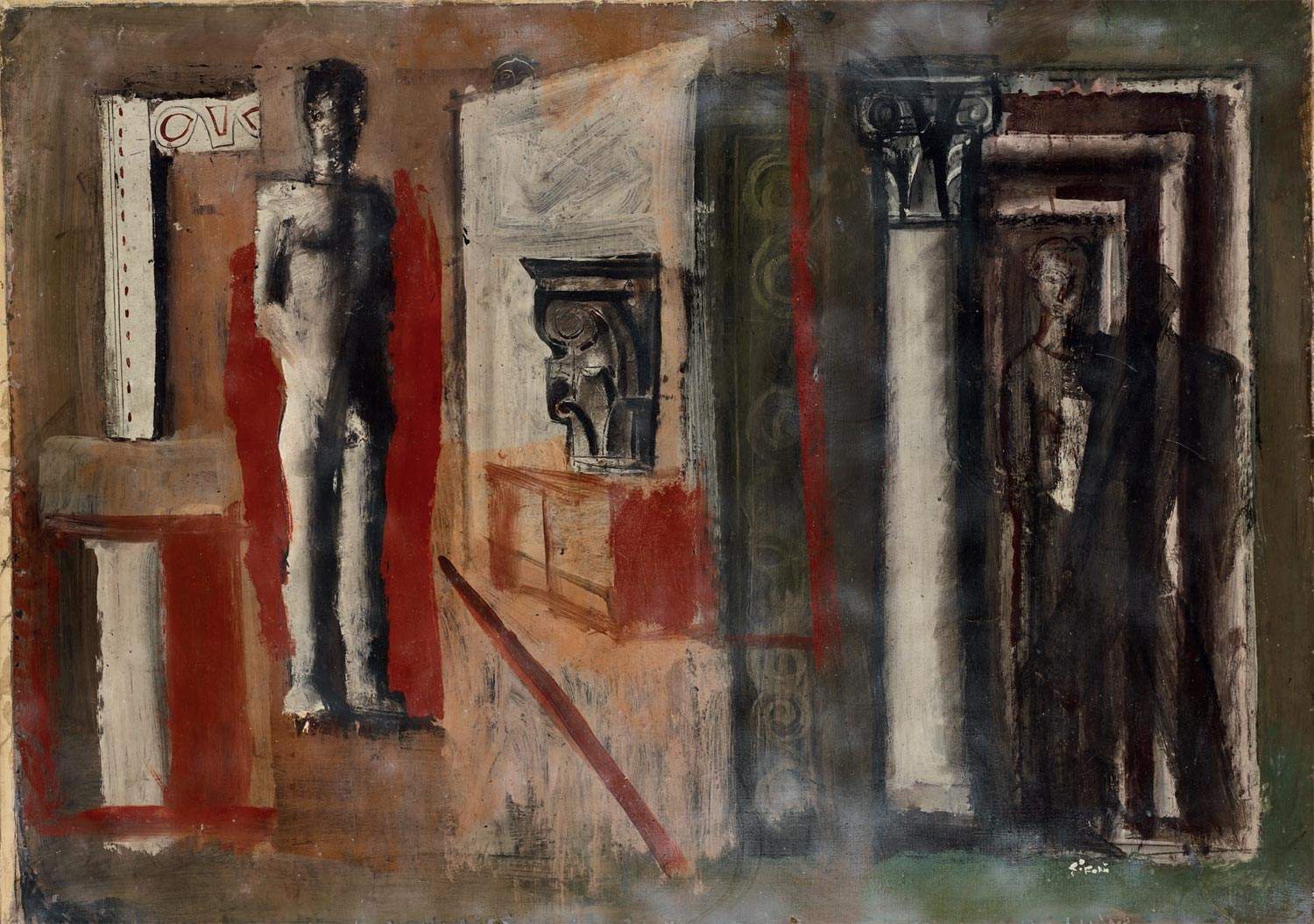

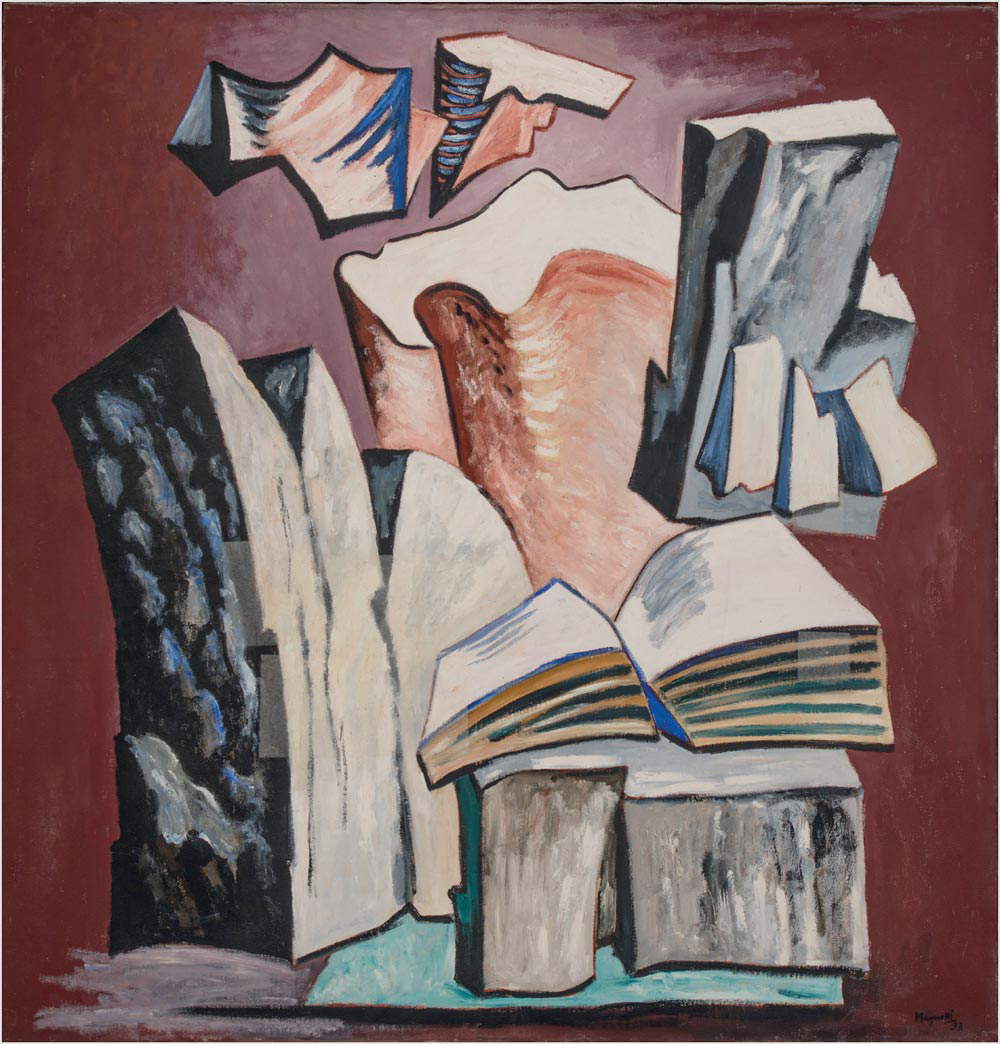

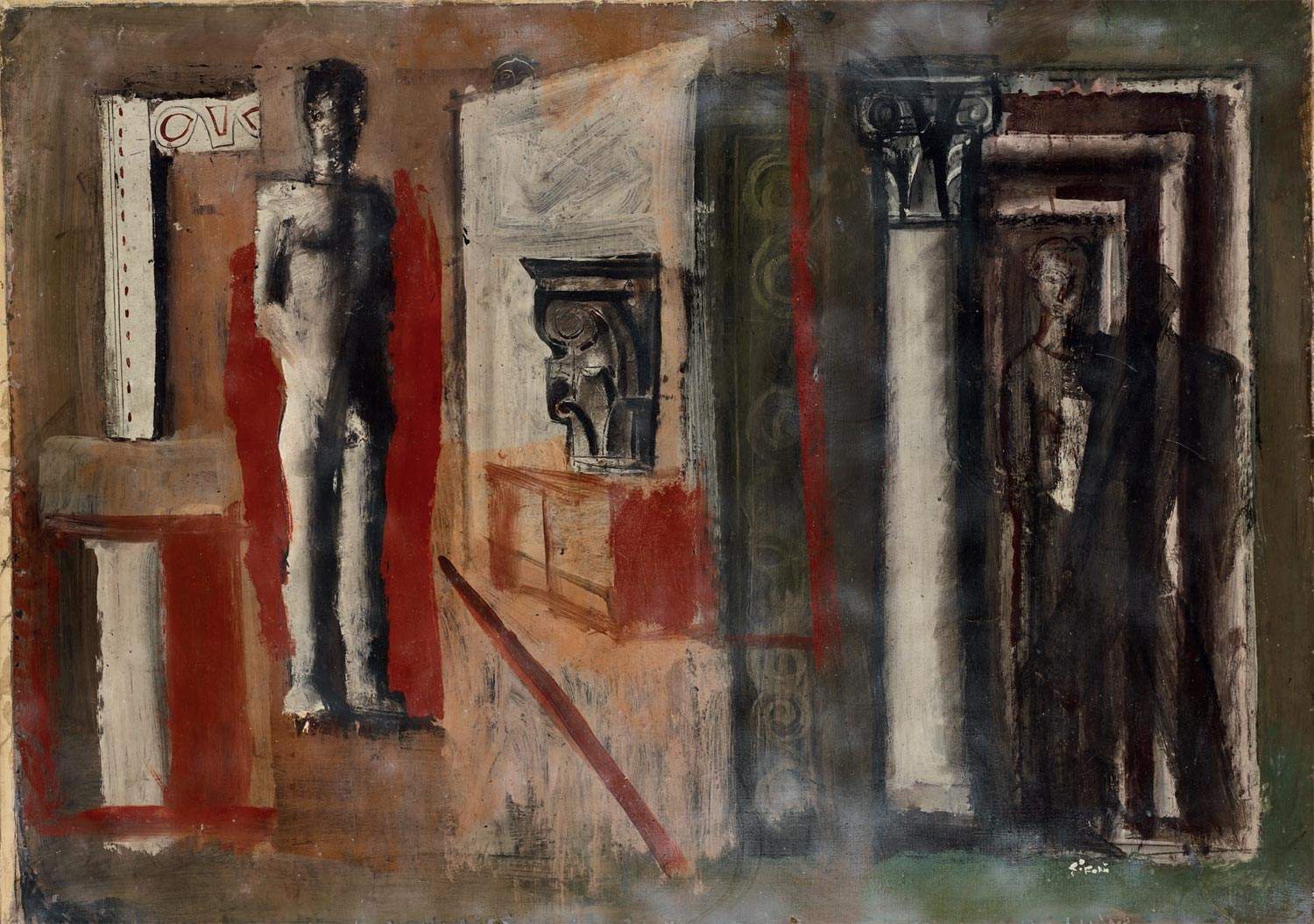

So, in the elegant rooms of the 19th-century Palazzo Cucchiari, it will be possible to admire more than 120 works of both sculpture (in marble, bronze, plaster, terracotta) and graphics (paintings, drawings, pastels), with the intention of providing the broadest possible view of a major artistic season in the Tuscan city. Dedicated to the paths of updating figurative languages and the artistic panorama of Carrara in the first half of the last century, the exhibition unravels through two artistic directions: on the one hand, that of the line leading from Art Nouveau to Novecentismo and abstractionism; on the other hand, that of volume, from solid verism to poetic naturalism and “spatial fragmentation,” in a continuous interweaving of sculpture, painting and neighboring artistic expressions. The Novecento a Carrara exhibition, on the two floors of Palazzo Cucchiari, follows these lines, exhibiting works by the greatest artists of the first part of the century, such as Libero Andreotti, Leonardo Bistolfi, Carlo Carrà, Moses Levy, Arturo Marini, Gino Severini, Mario Sironi, Ardengo Soffici, Lorenzo Viani, RAM, Thayaht, Fausto Melotti, and several artists from the local school such as Arturo Dazzi, Carlo Fontana, Sergio Vatteroni, Domenico and Resita Cucchiari, up to a pioneer of monumental abstraction such as Carlo Sergio Signori.

The works on loan come from private collections and museums such as the Uffizi, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna of Palazzo Pitti in Florence, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, the Mart in Rovereto, the Museo del Novecento in Milan, the Museo Novecento in Florence, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Turin, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Viareggio, the Museo Civico of Casale Monferrato, and the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca in Rome.

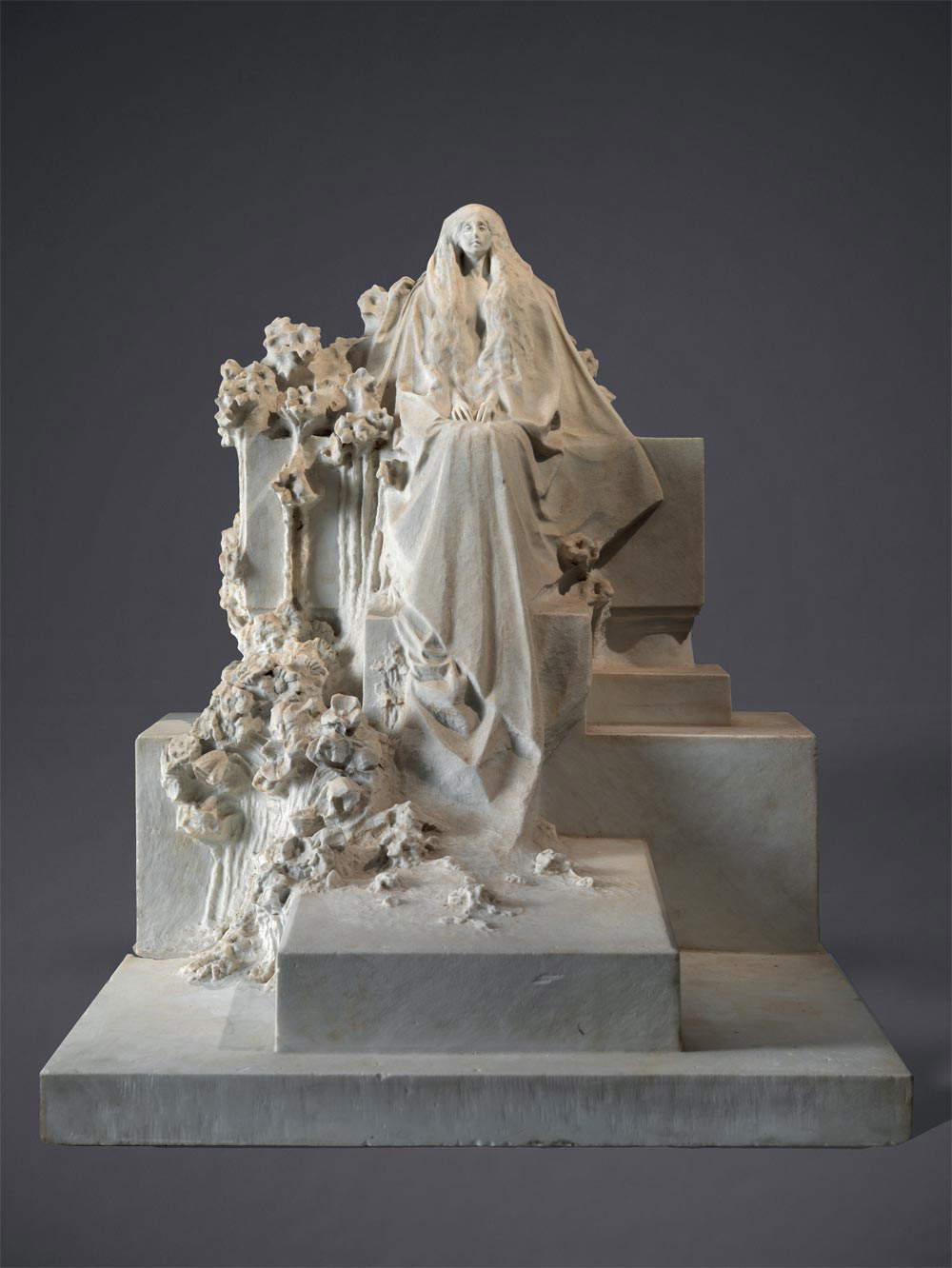

The exhibition’s narrative begins with Leonardo Bistolfi , who in the early 20th century introduced the themes and models of Symbolist sculpture into the technical and formal baggage of his craftsmen in Carrara, his workshops, and the taste for line and two-dimensional composition that helped renew the language of sculpture, at least until the first signs of the return to order after World War I would also direct Carrara’s workshops along the paths of classical recomposition of form.

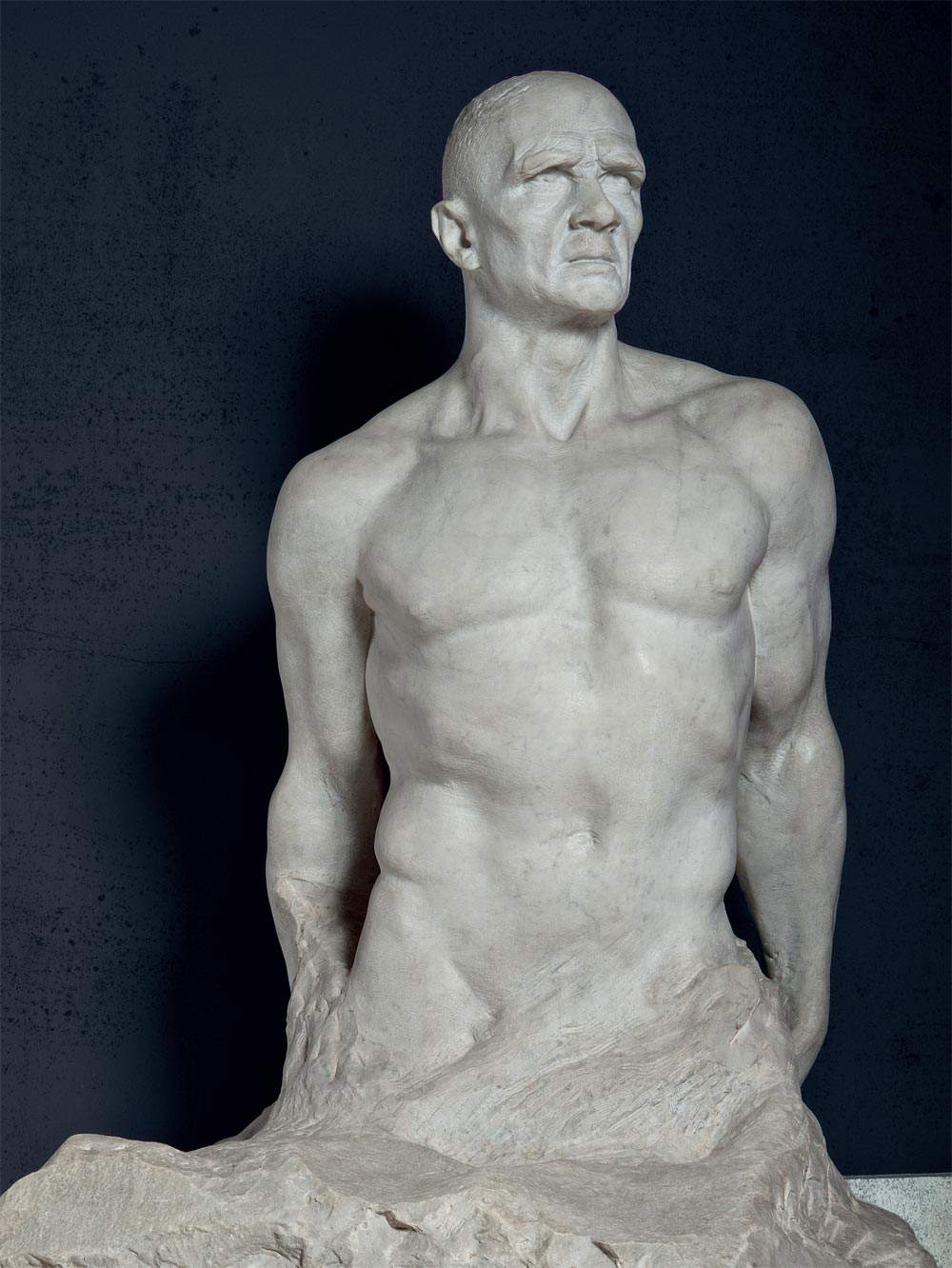

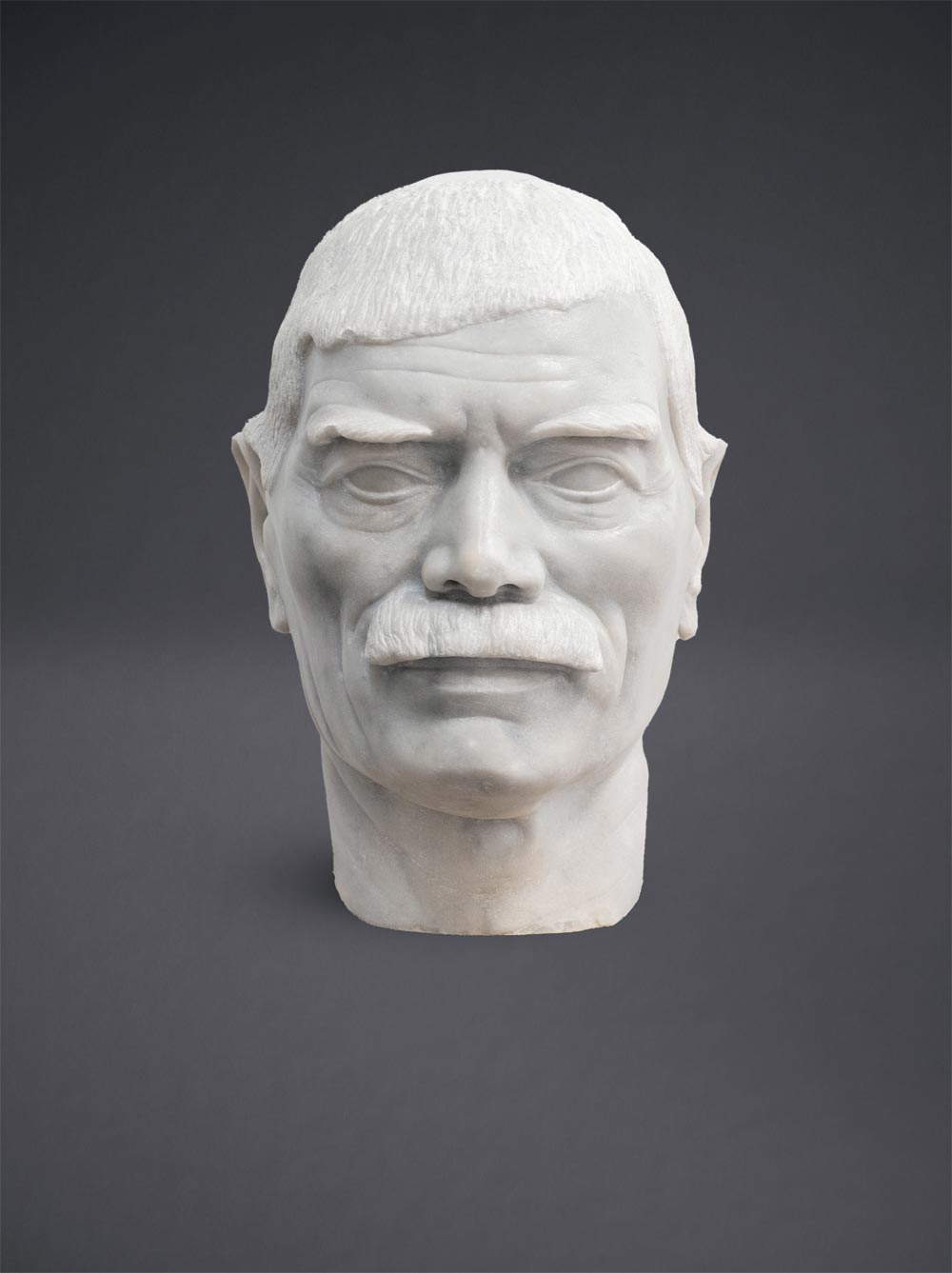

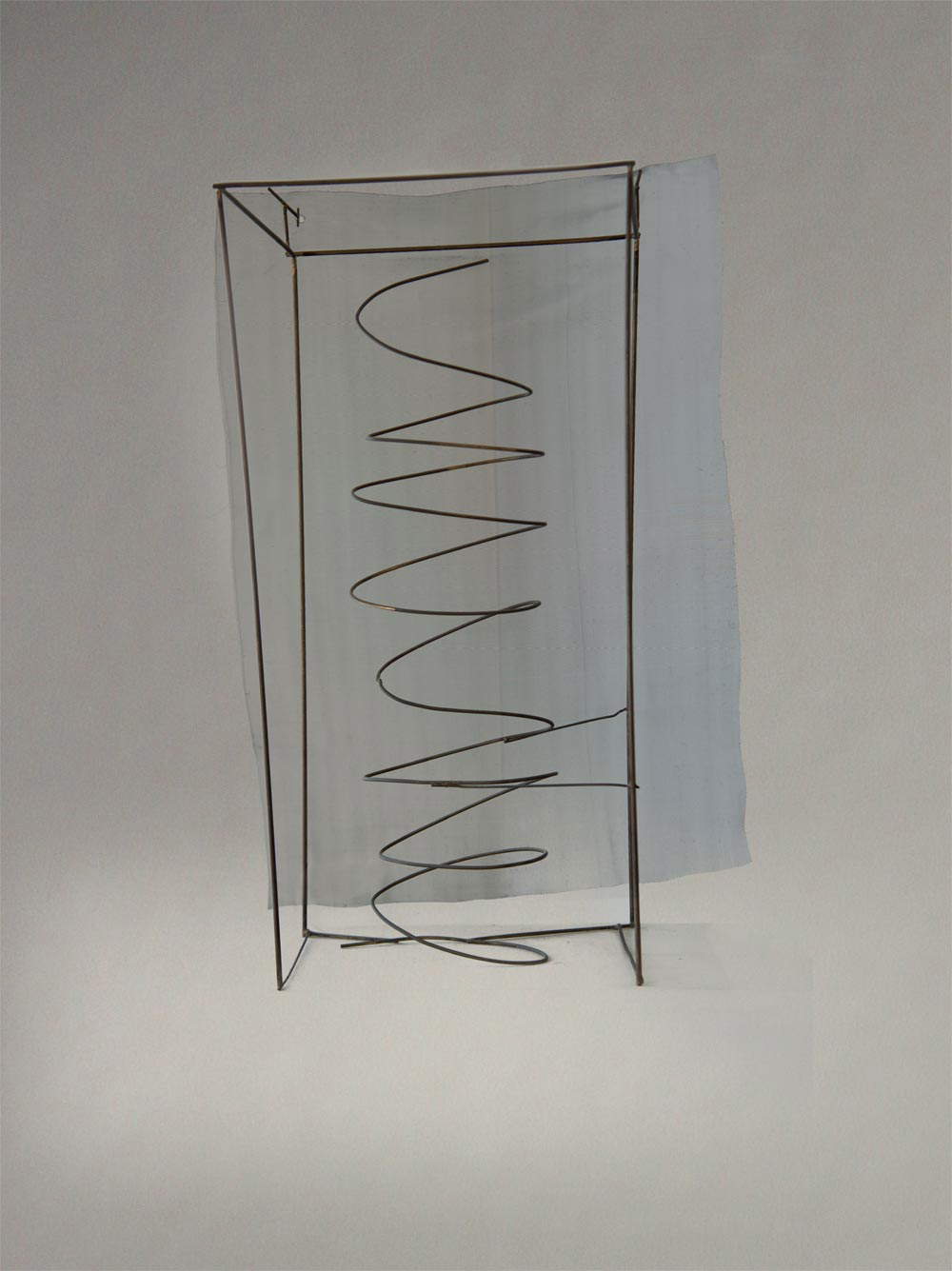

During the 1930s (the decade on which most of the exhibition focuses) the classical purity of Francesco Messina and the Novecentist forms of Mario Sironi and Fausto Melotti (who is also on display at Palazzo Cucchiari with one of his first abstract experiments, also from the 1930s) arrived in Carrara. The same period also marks the arrival of Arturo Martini, who, thanks precisely to Carrara and his relationship with Apuan studios and artisans, discovered unexpected possibilities for reinvigorating, from within and precisely in relation to what seems the most compromised material, the art of sculpture. The exhibition thus gives an opportunity to appreciate the Martini who alludes to the process of breaking down the form, who wracks his brain around the plastic function of shadows, who conceives and encloses in a form the Atmosphere of a head, the sculptor who senses that the sculpture of tomorrow will be what his pupil, Alberto Viani, is making, is nevertheless convinced that he must consume to the full every expressive potential of the figure. Viani himself would arrive in Carrara to give marble texture to the soft volumes of his plaster casts.

Meanwhile, abstract sculpture had found another way to land on Carrara marble. In 1946 Carlo Sergio Signori arrived from Paris with the requirement to create the Monument to the Rosselli Brothers for Bagnoles-de-l’Orne (the first monument of European art in abstract form), and the exact measure of the ability to renew an ancient tradition is given precisely by what might appear to be only an occasional episode, for in the end it will not be just by chance that Europe’s first abstract monument is made in Carrara and in a material under strong suspicion of passatism. Thus Carlo Sergio Signori, a “Parisian” from Milan, will become a “Carrarino,” inserting himself within the tradition of the marmorari, but in collision with the academic tradition, as was that of the continuity between Carlo Fontana, Arturo Dazzi and their numerous progeny who made their bones in the great public building sites and in the proliferation of monuments in the 1930s: Valmore Gemignani and Sergio Vatteroni, Aldo Buttini and Romeo Gregori, and then Francesco Piccini, Giorgio Salvi, Luigi Venturini, ending with the “professors,” also continuers of school teaching, Alderige Giorgi, Ugo Guidi, Felice Vatteroni.

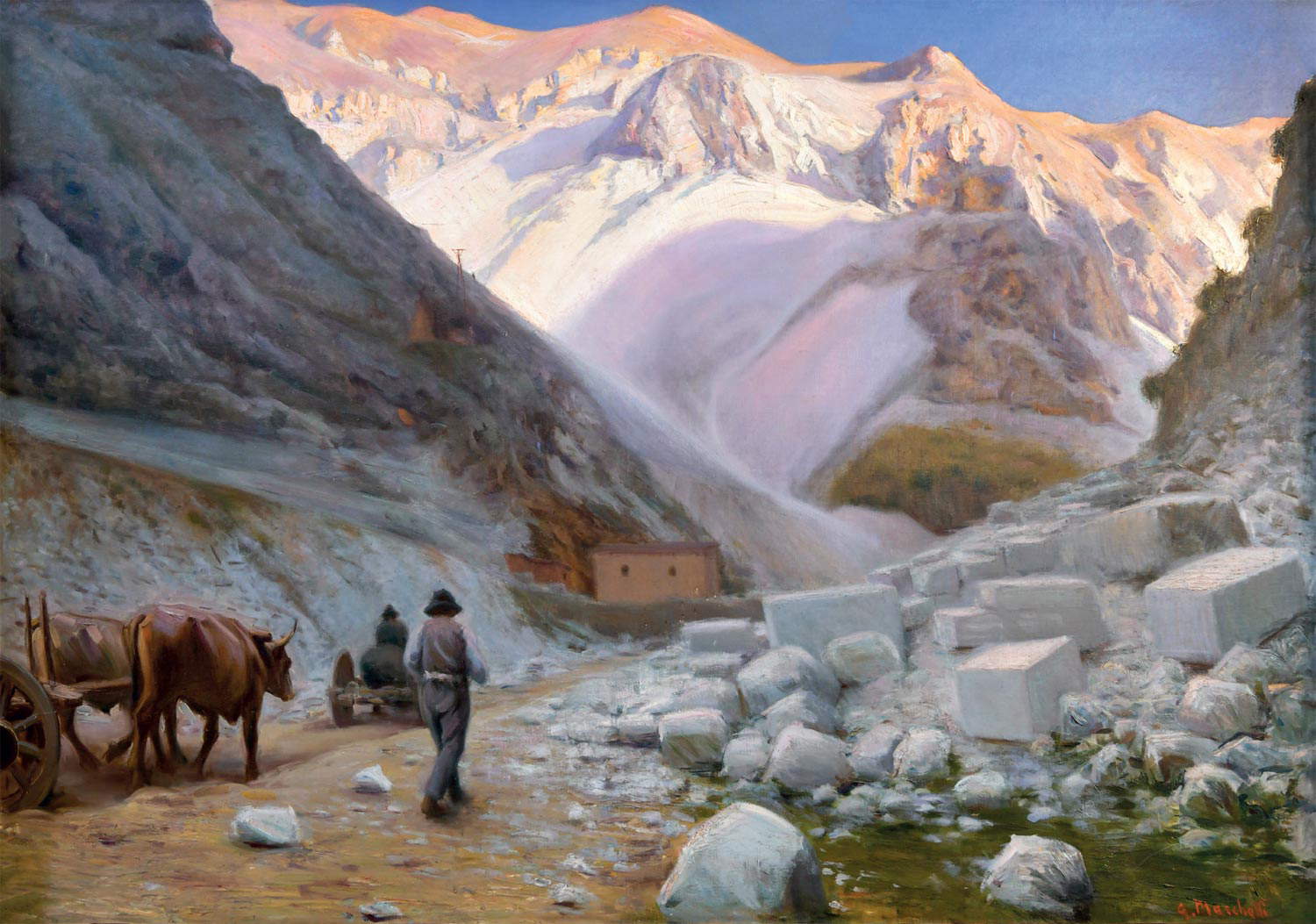

The paths of sculpture were then intertwined with those of painting, sometimes as a parallel discipline of the same artist (sculptors such as Arturo Dazzi, Sergio Vatteroni, Carlo Sergio Signori, and Arturo Martini practiced painting assiduously), while on the other hand the painter Mario Sironi made himself a sporadic “sculptor” in Carrara. Just as some suggestions to the updating of painting came to Carrara through the sculptors, Dazzi and Carrà and Soffici, Signori and Magnelli and Severini. And then the growth of painters in the academic scene, with the emergence of a figure like that of Pietro Pelliccia who of the Carrara Academy would become, first among painters, director. Accompanied by those for whom Carrara, its quarries and landscapes became pictorial motifs, starting with Lorenzo Viani, the protagonist of the "Republic of Apua,“ to whom a room of the exhibition is dedicated, but also a friend of Arturo Martini, who with the portrait of the Viareggio man would create one of his first works in marble. These would be accompanied by a long series of painters: some ”natives“ such as Giuseppe Viner or Giulio Marchetti and Gino Montruccoli; others, however, ”outsiders" such as Domenico Cucchiari, Uberto Bonetti, Ernesto Michahelles (Thayaht).

In those years, young people studying at the Academy of Fine Arts easily found the opportunity to complete their training by attending workshops, where it is possible to perfect the craft and at the same time witness the making of all sorts of sculptures, meet the artists, see the artisans at work. A context in which everyone teaches something just as they are there to learn something else: because sculpture is learned only where it is made.

The exhibition concludes at the years of reconstruction, on the threshold of Italy’s “second modernity,” when with the economic boom and the Council reviving the social as well as religious function of sacred art, a new season opened for Carrara sculpture and marble.

"With the exhibition 900 in Carrara. Artistic Adventures between the Two Wars, the Giorgio Conti Foundation," says President Franca Conti, "welcomes to the rooms of Palazzo Cucchiari a new chapter in the long history of Carrara marble and figurative culture. Following the exhibitions Canova and the Masters of Marble and After Canova. Sculpture in Florence and Rome, our halls give rise to an evocative, well-articulated and very indicative exhibition tour of Carrara’s modern history through the developments of its artistic and cultural traditions. Told from a very particular point of view, the economic and social development of Carrara and the Apuan region in the first half of the last century serves as a stage for the interweaving of the research paths of some of the leading masters of Italian art: sculptors and painters, natives or foreigners, who in the ’land of marble,’ vented, lowering themselves within a centuries-old tradition, their imagination and verified in the practice of work the actual possibility of participating in the processes of renewal of classical art. Therefore, the will of the Giorgio Conti Foundation, its mission as we like to say today, is once again to help our city to strengthen the awareness of the international prominence of the ’marble civilization,’ emphasizing the importance of enhancing the artistic aspects for the preservation of a unique, beautiful and therefore very precious material."

“In Carrara,” explains curator Massimo Bertozzi, “the 20th century was not a ’short century.’ The transition between the 1800s and the 1900s was quick, fast almost instantaneous; the new century began immediately, as it should be for every nascent thing. And one can see why. The ’bleak fin of the dying century’ had been all too tragic and painful, marked by two states of siege, the one of 1894 generated by intestine issues, the so-called ’Lunigiana uprisings’, with General Huesch’s Alpine troops chasing and capturing quarrymen up and down the Apuan Alps, and that of 1898, a preventive one against imported dangers, a consequence of the bread revolt in Milan, satiated with cannon fire by General Bava Beccaris. The ’countries of anarchy,’ as a poet whose work we shall hear more of, Ceccardo Roccatagliata Ceccardi, wrote in the Svegliarino, the paper of the Carraresi radicals, were crushed by a ’court of giberne’ which had hundreds of workers arrested, condemned, deported, who could return to their families very slowly, some only after years, waiting in the confines of the homelands for the next amnesty or pardon, which were then fortunately very frequent.” From these events begins the exhibition, which starts with Carlo Fontana’s Farinata degli Uberti brought to Venice in 1903, a work juxtaposed with Rodin’s lesson that becomes almost a symbol of the new Apuan artistic vitality, which can be said to have fully restarted with the publication of Apua Mater (1905) by Ceccardo Roccatagliata Ceccardi, a poet around whom some young people gathered and founded the magazine “Apua Giovane,” which, although short-lived, marks the act of origin of a sodality, which will be called “Apua Republic” or even Fratellanza Apuana, when around the five founders the best cultural and artistic intentions of the region stretching around the Apuan Alps, from Pontremoli to Carrara, from Massa to Viareggio, will unite. Here began the rediscovery of Apuan “myths”: references to ancient Luni, Dante’s sojourns in Lunigiana, Michelangelo’s in Carrara and Carducci’s in Pietrasanta animated a lively cultural scene, a climate in which the personalities of Viani, Viner, Fontana and several others would explode.

The First World War marked a watershed, following which even in Carrara there was a climate of return to order, represented in the exhibition by the works of Carlo Carrà, Ardengo Soffici and local artists who embodied this cultural temperament (above all Arturo Dazzi). Thus, if before the war there had been a frenzied focus among artists on secessionist fibrillations, there was now a need for regularity, which by many rivulets would end up in Apuania as well. Anomalous in this climate is the figure of Sergio Vatteroni, who while producing rhetorical works such as the Cavatore and the Scultore for Carrara’s Palazzo delle Poste (Post Office Building) keeps to the fringe positions, with the consequence that his art rejects almost on principle the idea that there existed an order to return to: his fidelity to the real happens in the groove of the secessions, with the return of an ornamental fluidity of line and the persistence of a tame expressionism and a brightness of impression that is almost divisionist. The exhibition does not lack hints of the celebratory exhibitions of the 1930s, nor of Mario Sironi’s Novecentismo and, as anticipated, Fausto Melotti’s experiments. Central to these years, however, is the figure of Arturo Martini who, precisely here, thanks to his relationship with Apuan studios and artisans, discovered unexpected possibilities for renewing, from within and in confrontation with what to him seemed the most compromised material, the art of sculpture. The abstract line, from Melotti, then follows the line of Alberto Viani and Carlo Sergio Rosselli, which ideally closes the exhibition by pushing into the second half of the century.

The exhibition opens, through Sept. 17, on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 4 p.m. to 8 p.m.; Fridays and Saturdays from 9:30 a.m. to 12 noon:30 and 4 p.m. to 11 p.m.; Sept. 19 to Oct. 29, 2023, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 8 p.m., Fridays and Saturdays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 9 p.m. Closure: Mondays. Special openings: Monday, August 14, 2023 9:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and 4-8 p.m.; Thursday, September 7, 2023 9:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and 3-11 p.m. Admission: € 10; concessions € 8; groups 10-29 people € 8; 30 and over € 7; free young people up to 18 accompanied by parents, handicapped and accompanying person, journalists with national card; Unicoop, Coop, Touring Club Italiano conventions provided. For information: phone +39 0585 72355, info@palazzocucchiari.it, website www.palazzocucchiari.it

|

| A major exhibition on the twentieth century in Carrara, from Sironi to Carrà , Martini to Melotti |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.