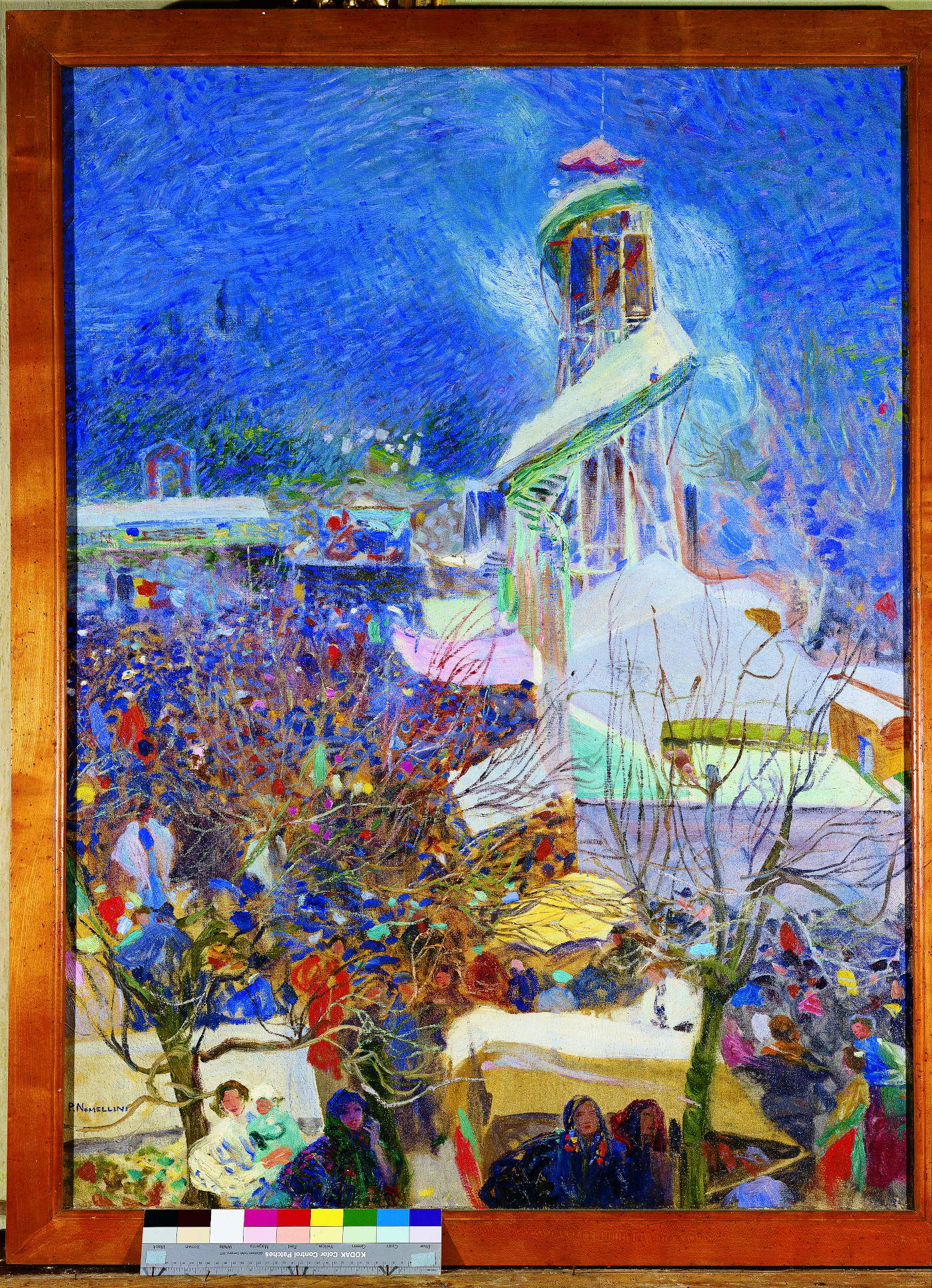

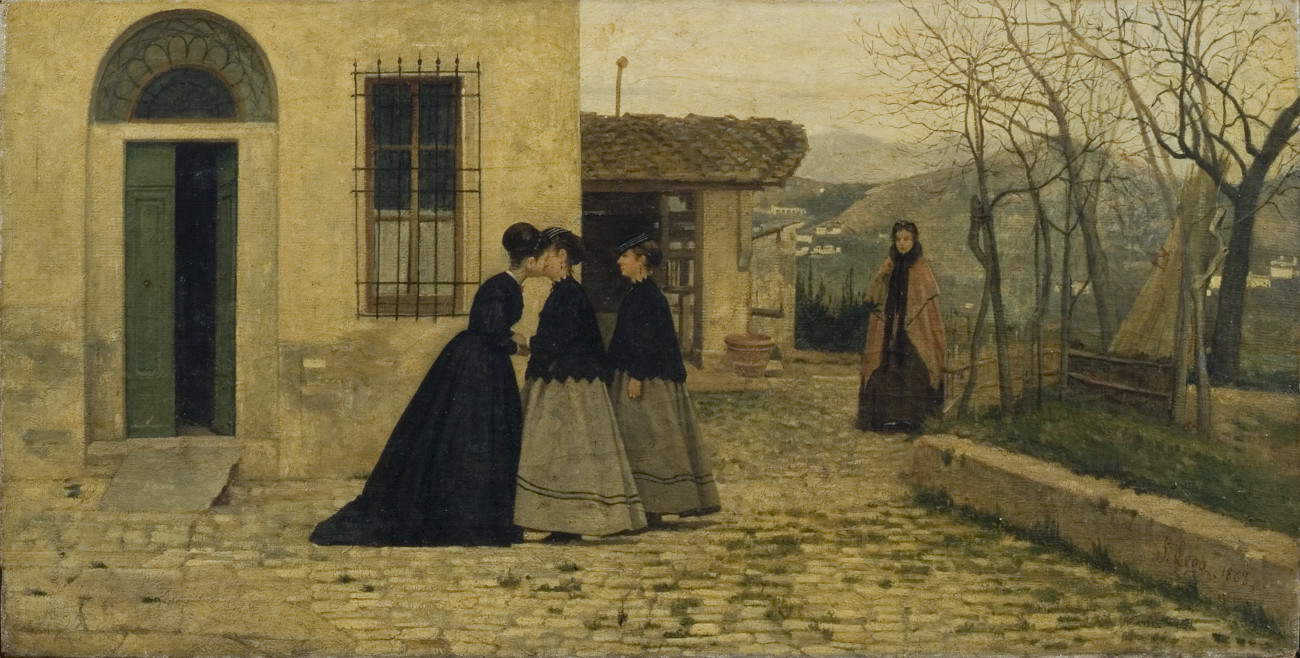

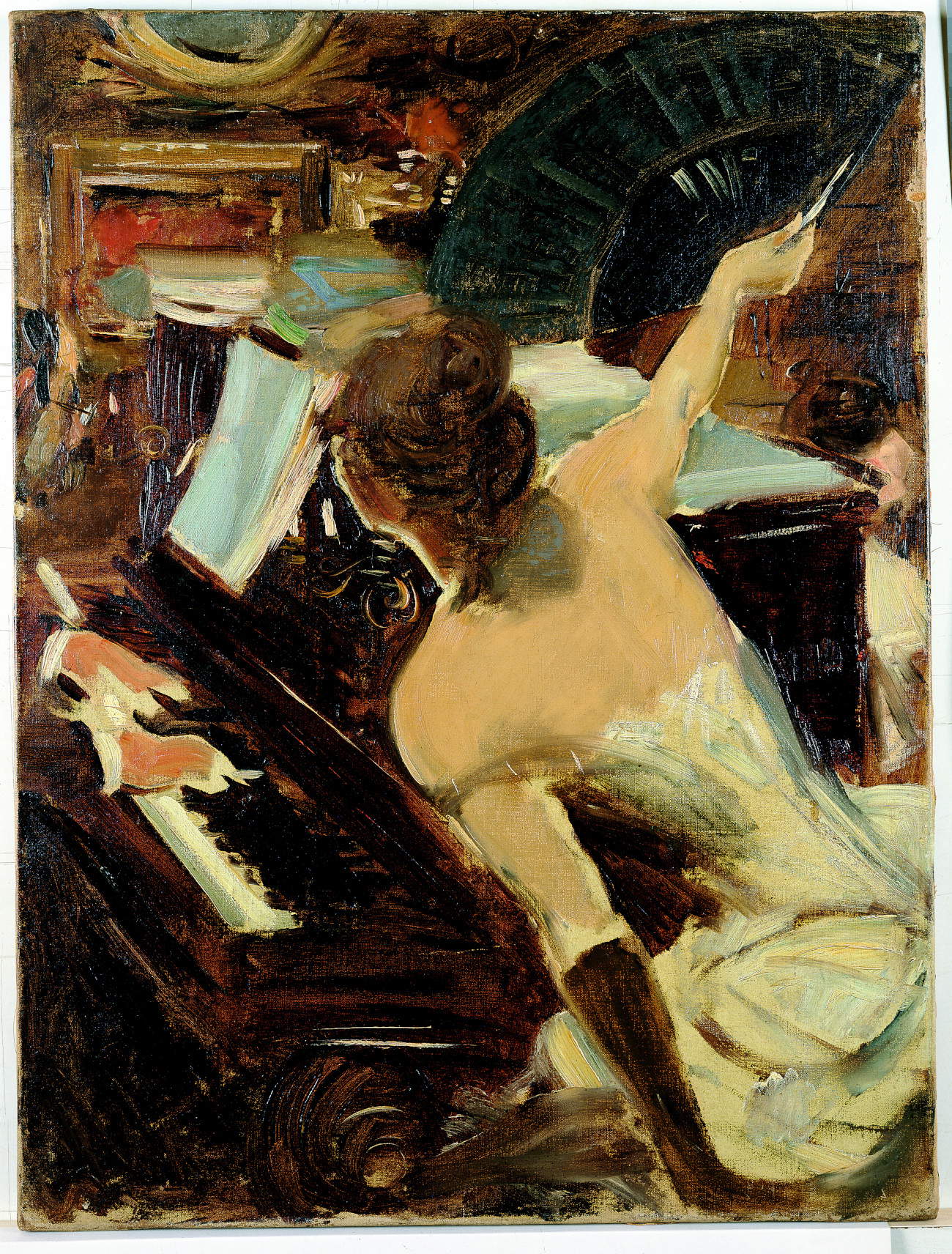

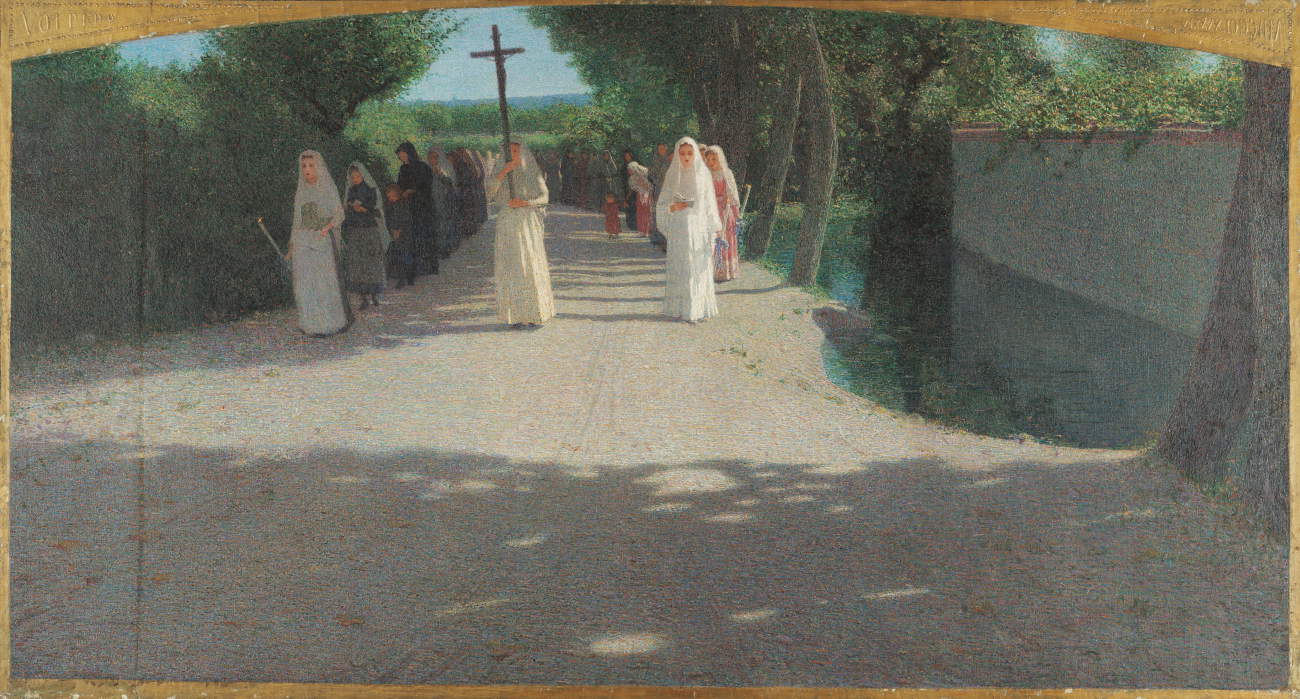

From June 29 to October 27, 2024, the exhibition halls of Palazzo Cucchiari in Carrara, home of the Giorgio Conti Foundation, will host the exhibition Belle Époque. Italian Painters of Modern Life. From Lega and Fattori to Boldini and De Nittis to Nomellini and Balla, curated by Massimo Bertozzi. The curator’s intent is to follow the traces of the mutations in painting after the Unification, from the overcoming of regional schools to the recomposition of a national imprint, in order to aim for an artistic culture suited to the modern times of the “New Italy.” An artistic journey that from the last impulses of the Macchiaioli leads to the effervescence of the Scapigliatura, to the final results of Divisionism: a journey that begins with Fattori and Lega, continues with Boldini and De Nittis, and culminates with Nomellini and Balla. Other artists will include Telemaco Signorini, Armando Spadini, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Federico Zandomeneghi and Vittorio Corcos, as well as Antonio Mancini, Tranquillo Cremona, Mosè Bianchi, Emilio Longoni, Angelo Morbelli, Gaetano Previati, and many others.

A total of about ninety works, including paintings on canvas and panel, watercolors, pastels, and bronze and plaster sculptures, will be on display, spanning a time span from 1864 to 1917.

The exhibition is divided into seven sections, to which an interlude is added.

The first section, entitled Modern Times, tells how painters, increasingly attracted to outdoor exercise and no longer limited to rural spaces and agricultural activities, now focus on urban spaces, streets and squares, as well as parks, public gardens and seaside locations. The second section, titled Home and Family: comforts of living and ways of living, focuses instead on how the home becomes a space to be exhibited, with living rooms, dining rooms, and studies serving as public spaces. Here, inhabitants show themselves off, pleasing themselves with their opulence, elegance or sobriety. We then move on to the third section, entitled The Painters of Modern Life: artists are no longer just the uprooted of bohemian life, but are beginning to enjoy a different social consideration. Welcomed into the most exclusive salons and circles, they themselves, their studios, and their families become subjects of painting, elegant and aesthetically striking. The interlude is devoted to sculpture: between romantic retreat and modernist anxieties, between religious and worldly mysticism, the features of Art Nouveau sculpture are outlined. The Pascolian symbolism of Leonardo Bistolfi and the aristocratic elegance of Paolo Troubetzkoy represent these contrasting feelings.

We continue with the fourth section, titled Old and New Myths, which focuses on modernity quickly becoming habit, prompting the continual search for distractions or other forms of stultification. This animates new desires toward an exotic or more natural elsewhere, or toward alternative worlds created by mystical and esoteric substances or practices, contexts in which some artists leave their testimonies. Then there is the fifth section entitled Povera Patria: the Italy of the people: ancient needs and new expectations. Despite everything, there is confidence in the future. The sixth section, Ladies’ Paradise, tells of how worldliness is linked to “social status”: at the theater, at the café, at the horse races, strolling on the corso or in the living room of the house. Women become protagonists; some are content to manage the family ménage, others engage in philanthropic and cultural activities, and some attempt to influence the country’s government. However, the status of women remains unchanged. The last section, titled Waiting for Tomorrow, focuses instead on the abandonment of naturalism, which predisposes the spirit and mind to the search for an expressive language appropriate to the reality of dreams and the suggestions of symbols. Pointillist painting thus becomes the natural expression of Symbolism, almost an Italian version of Art Nouveau, opening the field to the genesis and debut of the avant-garde.

In the first decades after Unification, the painting of the “new Italy” sought to find a national and international dimension, while remaining influenced by the tradition of regional schools. The focus shifted from the themes of life in the fields, with their frugal poetry of nature, to city life, animated by the search for material well-being and new worldly and cultural fulfillments. In this context, intellectuals, writers, composers, and artists are asked to consider differently entertainment, leisure, and the intelligent use of leisure time, which for some social classes becomes socially useful, creating a new way of living in private and appearing in public.

The business world, high finance, and aristocratic enterprise, as well as academies and public institutions, became promoters of the fine arts, with collectors and patrons becoming figureheads for artists and merchants. However, the betrayal of the ideals of the Risorgimento and the conservative involution of the national political class lead to the disenchantment of intellectuals. Only the most famous artists manage to break free thanks to the private recognition of the new entrepreneurial bourgeoisie andliberal aristocracy, who were also disappointed by the outcomes of the Italian “revolution.”

In this period, history painting, with its regional “patriotism,” is replaced by representations of modern life, sustained by clear narrative rather than ethical intentions, influenced by literary, especially French, suggestions rather than by the updating of figurative languages. The cooling of ideal impulses and the lure of worldly seductions drove the artists of the new generation to feelings of revulsion and rebellion. Influenced by the “bohemian life,” the “dualisms” of the scapigliati and their fellow artists emerged: on the one hand, the drive toward lofty and noble ideals; on the other, complacency with the more degraded aspects of civic life.

During the “Giolittian Age,” an apathetic and stunted period for the new Italy, only the reaction of artists seems to be in step with the times. Some painters manage to decant from Divisionist painting the last real Italian contribution to European art, with Futurist intemperance and Metaphysical divination.

For more info you can visit www.palazzocucchiari.it

Finestre Sull’Arte is a media partner.

Hours: June 29 to Sept. 15, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 4 to 8 p.m.; Fridays and Saturdays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 4 to 11 p.m. Sept. 17 to Oct. 27, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 3 to 8 p.m.; Fridays and Saturdays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 3 to 9 p.m. Closed Mondays.

Tickets: Full 10 euros, reduced 8 euros, 8 euros for groups of 10 to 29 people, for groups of more than 30 people 7 euros; 5 euros for university students. Free for young people under 18, handicapped and accompanying person, journalists with national ID. Unicoop, Coop, Coop Liguria, Touring Club Italiano conventions are provided.

|

| A major exhibition in Carrara on the Belle Epoque and Italian painters of modern life |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.