A major anthology in Trieste dedicated to Escher's impossible worlds

Maurits Cornelis Escher (Leeuwarden, 1898 - Laren, 1972) is universally known in the art context for his so-called impossible worlds, which he created by adopting mathematics, precision, repetitiveness and, above all, paradox. Strongly fascinated by mathematical designs, the artist made repetitive patterns of interlocking tessellations and paradoxical representations of infinity in his graphic works to lead anyone who paused to look at them into unique and imaginative worlds where art, science, mathematics, physics and design mutually influenced each other into masterpieces of the impossible. Elements that also animate the approximately two hundred works by Escher that, until June 7, 2020, are on display in a major exhibition entirely dedicated to the Dutch artist in Trieste’s Salone degli Incanti, where the public has the opportunity to familiarize itself with his art.

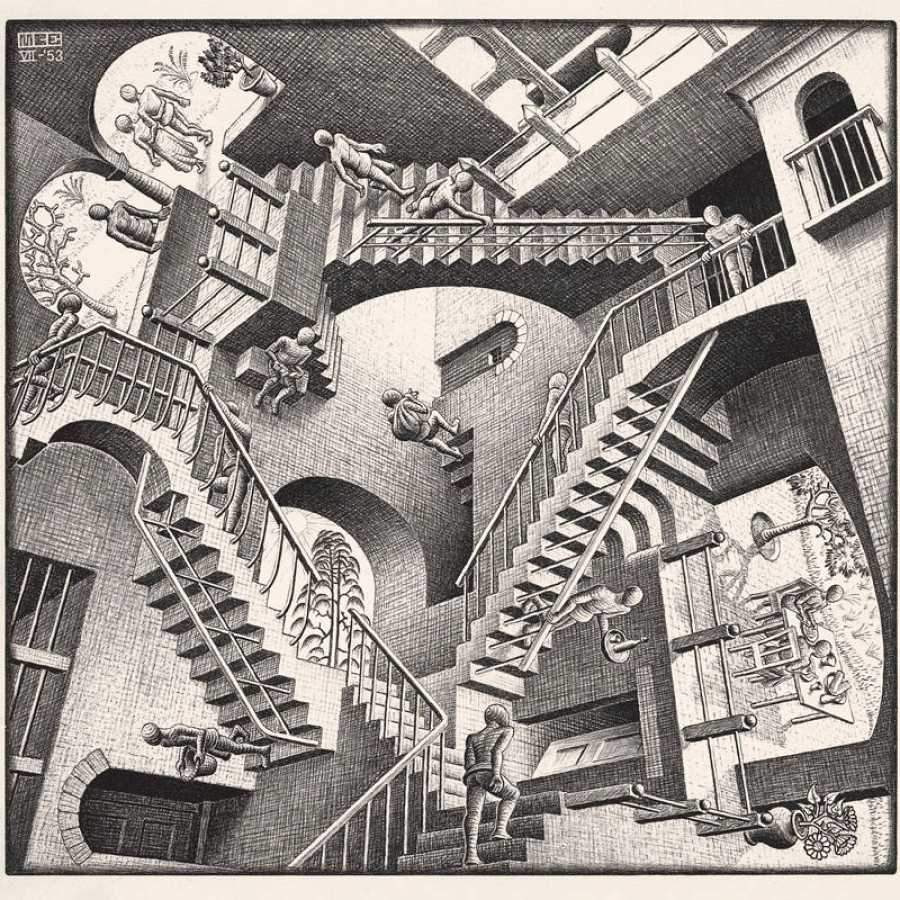

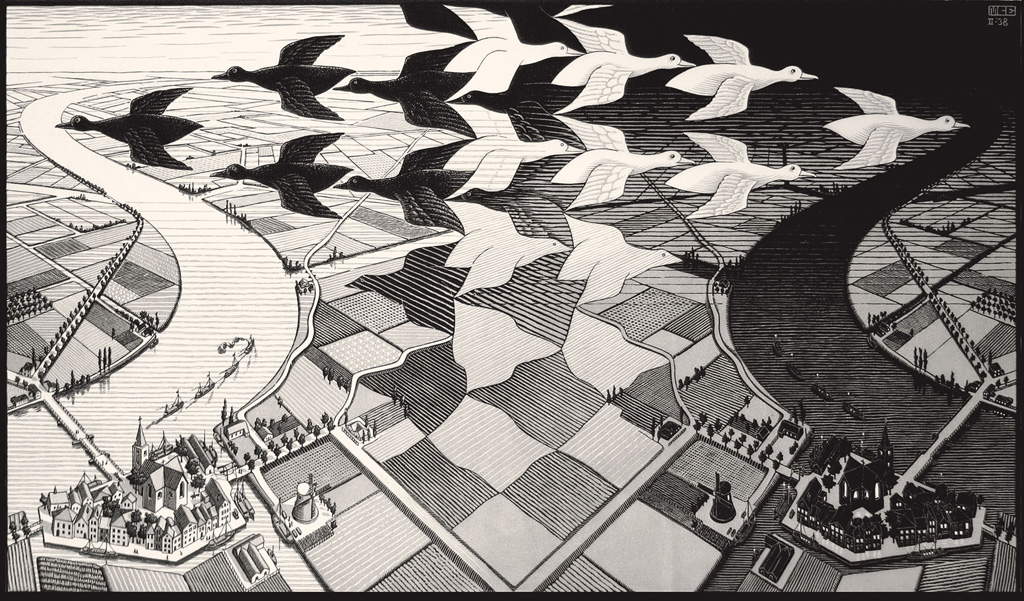

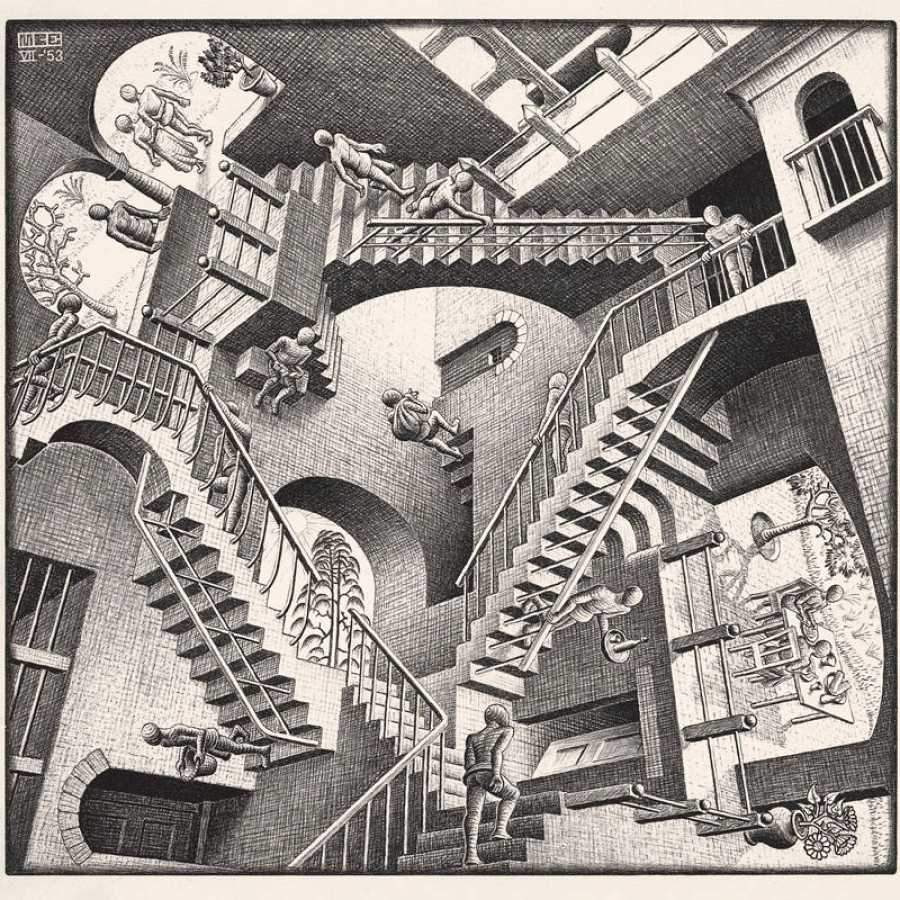

An interplay of different perspectives characterizes many of his works, such as the famous Relativity, where it becomes quite complicated for the viewer to understand which is the “right” direction of the staircases that dominate the entire graphic work: in fact, here three worlds coexist simultaneously, as can be seen from the figures ascending and descending the various staircases or looking out looking in front of them, but their “in front” almost never corresponds to that of other figures. It would be necessary to adopt the system of Cornelius Roosevelt, Teddy’s grandson and the first major collector of Escher in the United States, who decided to hang the work on a revolving stand. If relativity is typical in the artist’sillusory universe, since it is the observer who chooses the point of view, no less important is metamorphosis: the works characterized by the latter are a continuous transformation of forms and figures throughout the entire work. Exemplary in this aspect is Metamorphosis II, considered the artist’s masterpiece: tessellations of triangular, square and hexagonal bases alternate with landscapes that recallItaly, a country the artist first visited in 1922 and where he settled for many years, and chess figures that recall Escher’s time in Switzerland. In Day and Night, however, the artist takes the Dutch countryside as seen from an airplane and, inspired by the succession of crops, creates geometric modules with which he is later able to transform cultivated fields into the flight of black and white ducks.

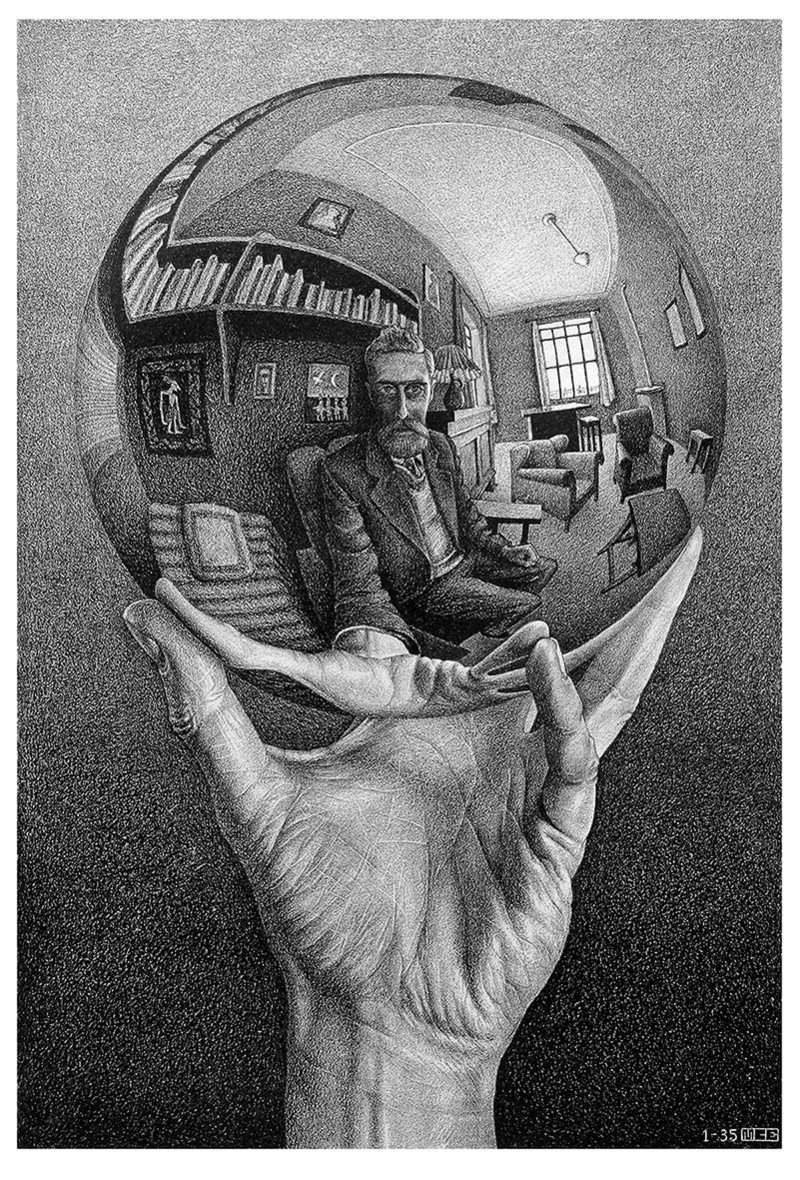

The space depicted by Escher is further modified through reflective surfaces, as in the case of Hand with Reflecting Sphere: it was made in the studio of the Roman house on Via Poerio, as can be seen after all in the reflected image of the environment in which the artist himself is also reflected. “The ego [of the artist] is invariably at the center of his world,” Escher self-deprecatingly stated in commenting on this work.

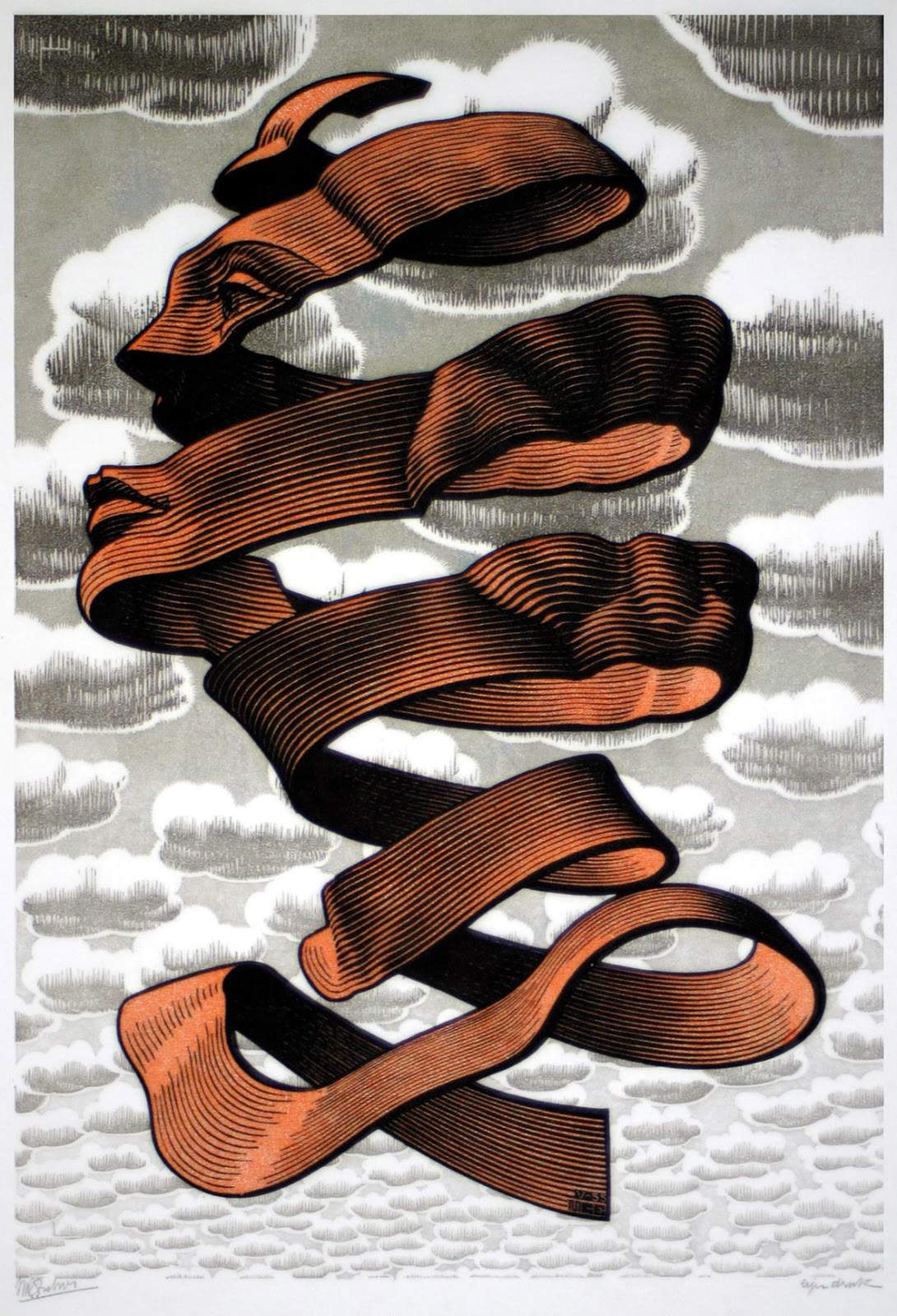

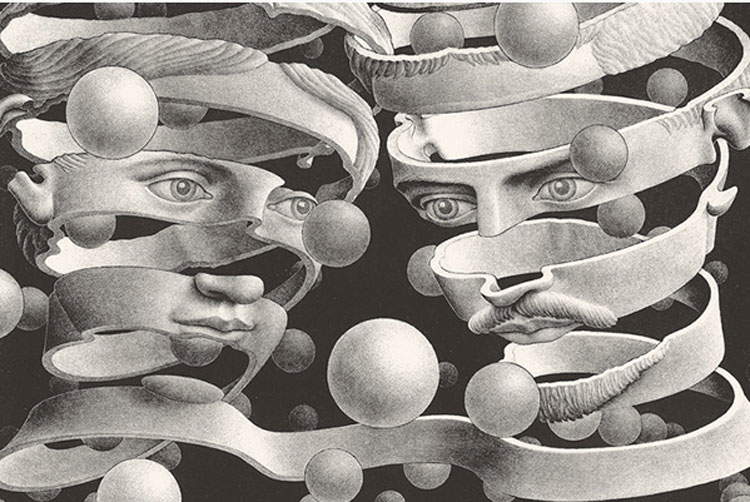

In other cases the space is entirely occupied by large geometric solids within which are enclosed animals, two chameleons in the case of Stars, or is “decorated” by ribbons that themselves form outlines of human figures: Examples are Peel, where a spiral ribbon constitutes the face of a woman floating in the air like a hollow sculpture, and Bond of Union, in which Escher portrays himself and his wife in a single spiral ribbon, joined by means of their respective foreheads, to represent an indissoluble bond that endures in time and space.

As the graphic artist that he was, Escher first created the matrix, which he carved by hand, and then through this he created works of art by transferring the image, like an ancient printer. There are about 450 prints made by the artist using mainly five different etching techniques: linocuts, woodcuts, head woodcuts, etchings, mezzotints and lithographs. The first three are prints made by the technique of relief block engraving, for which a relief engraved image, ink and material to print on were required: originally they were mostly transferred to cloth and only later to paper. Lithographs were made by means of an engraved image on a stone surface, while mezzotints and etchings were made with a smooth copper plate covered with wax: the plate was immersed in an acid solution; in this way the wax coating repelled the acid, but in the engraved areas the acid corroded the metal. All that remained was to remove the protective material from the plate and cover it with ink that concentrated in the chemically etched lines.

Also on view for the first time in the world at the Trieste exhibition is the series The Days of Creation, a series of six woodcuts that Escher executed between December 1925 and March 1926 that depicts the first six days of the creation of the world. As described in the book of Genesis, on the first day God created the earth and the light and the spirit of God hovers above the waters (here represented by a bird in flight; on the second day He parted the waters (this work by Escher is considered one of his early masterpieces, inspired by Hokusai’s Great Wave; in fact the Japanese woodcut was present in the artist’s paternal home); on the third day he created plants; on the fourth day he created the sun and moon; on the fifth day he created birds and fish; and on the sixth day he created animals and man.

Upon completion of the six woodcuts, the artist produced a kind of frontispiece with the image of a bird, the names of the prints in Italian and the corresponding Bible verses. Already the five birds at the top hint at the use of tessellations with animated figures in Escher’s works after 1936.

“Wonder is the salt of the earth,” stated the artist, and his extraordinary graphic works certainly exemplify this. Below are some images of works in the exhibition.

|

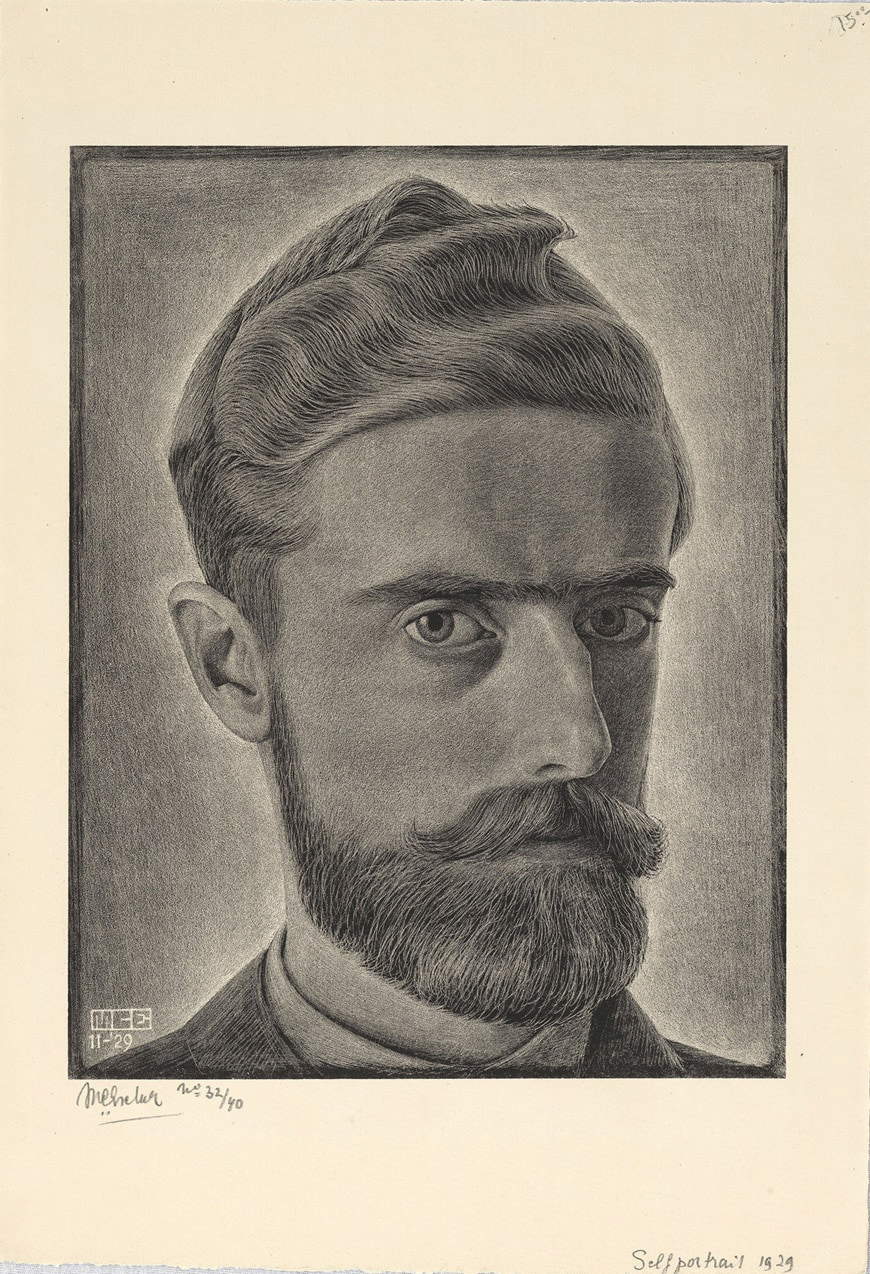

| Maurits Escher, Self-Portrait (1929; lithograph, Bool 128, 264 x 203 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, Relativity (1953; lithograph, Bool 389, 277 x 292 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, Metamorphosis II (1939 - 1940; woodcut, Bool 320, 192 x 3895 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, Day and Night (1938; woodcut, Bool 303, 391 x 677 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, Hand with Reflecting Sphere (1935; lithograph, Bool 268, 318 x 213 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, Peel (1955; woodcut and head woodcut, Bool 401, 345 x 235 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, Bond of Union (1956; lithograph, Bool 409, 253 x 339 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Maurits Escher, The First Day of Creation (1926; woodcut, Bool 104, 280 x 377 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| A major anthology in Trieste dedicated to Escher's impossible worlds |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.