A group show at the National Gallery on how human society leads to environmental catastrophe

The National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome presents from October 24, 2022 to February 26, 2023 the group exhibition Hot Spot. Caring For a Burning World, curated by Gerardo Mosquera.

The title echoes that of Mona Hatoum ’s work of the same name(Hot Spot III, 2009) included in the exhibition: a large iron and neon installation depicting the planet Earth lit by a red light symbolizing the conflicts that make it red-hot. The work is about how the disruptive way in which human society has been organized seems to be leading to environmental catastrophe. The failure of modern design and the very possibility of harmonious development of humanity in its environment is currently more than evident and is at the center of contemporary debate.

The exhibition at the National Gallery aims to bring together the multiple reactions to these conditions by artists. The works on display aim to delve into the complexity of the current situation, proposing an aesthetic activism intended to stimulate reflection and raise awareness of the disaster, to imagine a different relationship with the planet.

“It is natural for art to deal with such burning issues: many artists throughout their careers have done so in a militant, responsive and relevant way, but this exhibition, on the other hand, contributes to ecological-social critique through a more indirect, but no less urgent and timely path,” the curator explains. “The exhibition path does not consider the issue as something specific, but opens it up and amplifies it by exploring other aspects, sometimes ambiguous and contradictory, or harmonious, suggesting the possibility of a rebirth of the natural environment, since life on Earth has an enormous capacity for resilience.”

Designed specifically for the spaces of the National Gallery, the exhibition features the works of twenty-six artists from around the world and belonging to different generations: Ida Applebroog (Bronx, New York, 1929), John Baldessari (National City, California, U.S., 1931- Los Angeles, California, U.S., 2020), Johanna Calle (Bogotá, Colombia, 1965), Pier Paolo Calzolari (Bologna, Bologna, 1943), Alex Cerveny (São Paulo, Brazil, 1963), Sandra Cinto (Santo Andre, Brazil, 1968), Jonathas de Andrade (Maceio, Brazil, 1982), Filippo de Pisis (Ferrara, 1896- Milan, 1956), Mona Hatoum (Beirut, Lebanon, 1952), Ayrson Heráclito (Macauba, Brazil, 1968), Ibeyi (Lisa-Kaindé Diaz and Naomi Diaz, Paris, 1994), Chris Jordan (San Francisco, California, U.S., 1963), Juree Kim (Masan, South Korea, 1980), Glenda León (Havana, Cuba, 1976), Ange Leccia (Barrettali, France, 1952), Cristina Lucas (Jaen, Spain, 1973), Cecylia Malik (Krakow, Poland, 1975), Gideon Mendel (Johannesburg, South Africa, 1959), Raquel Paiewonsky (Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic, 1969), Michelangelo Pistoletto (Biella, 1933), Alejandro Prieto (Guadalajara, Mexico, 1976), Davide Rivalta (Bologna, 1974), Andrea Santarlasci (Pisa, 1964), Allan Sekula (Erie, Pennsylvania, U.S., 1951 - Los Angeles, California, U.S., 2013), Daphne Wright (Longford, Republic of Ireland, 1963), Rachel Youn (Abington, Pennsylvania, U.S., 1994).

If the works of Mona Hatoum and Pier Paolo Calzolari recount the extreme effects that climate can achieve through visual and material contrast, the disruptive force that elements, such as water, can manifest is reported in Kim Juree’s Flooded, where the dissolution of a clay architecture is observed.

Gideon Mendel, on the other hand, has documented with his photographs the devastation left by the unleashing of floods in different parts of the planet. Somewhere between documentation and staged photography, the didactic approach in these works is reinforced by the aesthetic component. Similarly, through evocative images of rising waters defying gravity, Ange Leccia ’s video suggests the idea of rising sea levels.

The staggering growth of the human population and its uncontrolled expansion with the consequent exploitation of environmental resources also bring to the forefront the relationship with the other living beings that inhabit the Earth and that, during the lockdown, have seen themselves reclaiming vital spaces. These appearances recur in Davide Rivalta’s sculptures, whose endangered gorillas welcome the public at the Gallery’s entrance.

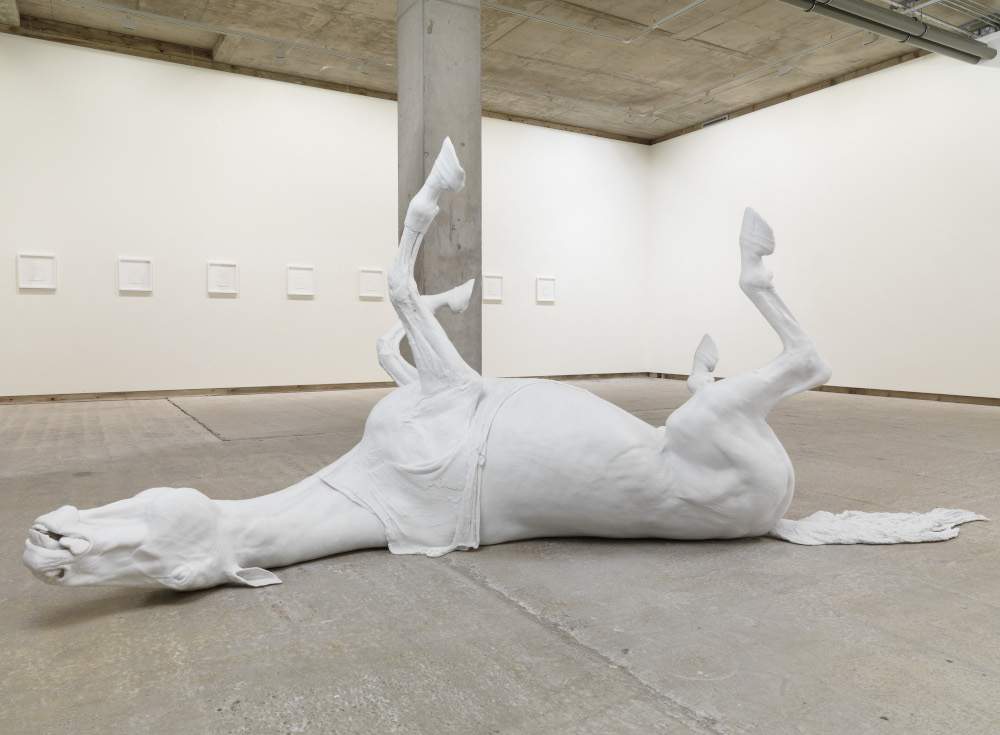

The biodiversity crisis, the staggering extinction of animal and plant species, and criticism of the violent development of urbanized areas are central to the works of Daphne Wright and Ida Applebroog, and emerge with subtle irony in the small roadrunner stopped at the U.S.-Mexico border portrayed by Alejandro Prieto. There is no shortage of contradictions, as in the image in Jonathas de Andrade’s video in which the fisherman embraces and caresses the fish he is agonizing over.

The increase of population on the planet goes hand in hand with the overproduction of goods and consequently with the increase of waste and refuse: it is garbage represented by Chris Jordan in its massiveness. The world’s increasing processes of urbanization and technologization have little regard for the natural environment, giving rise to phenomena such as the dark tides portrayed by Allan Sekula. Plants agitated by machines in Rachel Young ’s madly moving sculptures seem to comment on this, as do genetic manipulation and the shift to cyborgs and robotization. Johanna Calle ’s visual lyric acts in the opposite way: she builds a tree with a typewriter.

Trees also figure prominently in the works of Cecylia Malik, who intends to reflect on the indiscriminate deforestation that has taken place in Poland by contrasting the severed trunks with life, with mothers sitting on what remains of the forest and nursing their children. Michelangelo Pistoletto with five mirrored tree trunks creates an open image about the relationships between human presence and the environment. In his painting, Alex Cerveny transforms the human silhouette into a fruit tree, surrounded by birds.

Other works remind us of how all too often humans place themselves in a position of superiority to nature, as John Baldessari does in his video by imposing himself on it. Cristina Lucas reacts precisely to the patriarchal dimension with radical feminism: in her classic video performance she destroys a copy of Michelangelo’s Moses, rebelling against the tables of the law dictated by power.

The video clip by the Ibeyi duo seems to express the opposite of hierarchical control over nature in a song addressed to the river, as if it were Ochún, the Yoruba goddess of fresh water, to whom the artists sing in the Nigerian language. On an entire gallery wall, waters float in the sky, in a liquid and poetic cosmology, painted especially for this exhibition by Sandra Cinto. Andrea Santarlasci ’s work, on the other hand, can be seen as an expression of the contrast between nature and the built world. Ayrson Heráclito and Joceval Santos, artists and Candomblé priests, perform a grand ebbó, a ceremonial “cleansing” of the world carefully prepared according to Yoruba traditions in Brazil. The work thus hybridizes Afro-Brazilian sacred rituality with performance in an imaginative attempt to rid the earthly sphere of the evils that plague it.

Other artists allude to a harmonious coexistence with nature, as in the photograph of yucca fingers enacted by Raquel Paiewonski, where the hand becomes an edible root that was the main food cultivated by the Tainos in the pre-Columbian Caribbean, and continues to be important to the region’s diet today. Glenda León suggests a renaissance in her flowery piano.

These are works based on methodological plurality, the communicative power of image, poetry and semantic thrust. Some works were created without the intent to comment on ecological issues, but were included for their ability to contribute to the articulation of the theme. Each artwork is polysemic and always open to interpretation. The exhibition does not intend to spread slogans, but wants to take care of the world through art as well, inviting us to reflect in different and subjective ways on the serious problems of the planet in their complexity and not only on the ecological and social level.

Image: Daphne Wright, Stallion (2009), marble dust and resin, 160 x 380 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London. Photo by Stephen White

|

| A group show at the National Gallery on how human society leads to environmental catastrophe |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.