With Tracey Emin we all love better

With Tracey Emin we all love better. Tracey is perhaps the first artist since Frida Kahlo to transform the last taboos such as vulnerability and illness into a new artistic expression by transcending the current academic hierarchy. If feelings and emotions had not been sufficiently investigated by Romanticism and Expressionism, Tracey fuses the two currents together by re-actualizing their themes, painting sex and nudity as did Egon Schiele, pain and torment as did Edvard Munch, both of whom are widely cited and invoked in her work as her highest references, but also stitching the names of her lovers on bedspreads and curtains, illuminating stations and ministries with her neon declarations of love. Before Tracey, instinct and spontaneity had already been used in a direct and brute manner by Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem De Kooning promoted by the CIA in the 1950s to compete with both the Realist Socialism of communist nations and the still dominant European art market. If we now know that spontaneism and arbitrariness in art, originating in Dada, favor the American market more than a more global libertarian ideal, we can investigate its usefulness and relevance through Tracey’s immoderate use of it.

Tracey’s art is votive, sanguine and carnal, not representational: she paints, sculpts and sews not her traumas but with her traumas, with her physical and psychological wounds, unfiltered. Rape, abortions, cancer, operations, and disability are her palette or clay with which she reshapes and redefines not only her own relationship to her body, her sex, and her femininity but our identity that has meanwhile become fluid (and thus undefined) with the over-riding wokism, still a child of liberalism. Like Tracey, the German-fathered Mexican Frida Kahlo, a survivor of a terrible car accident, whom Breton so much wanted to integrate into his now dying movement but in fact surrealist only technically, knew how to accept her frailties by refusing to see them as infirmities, in fact making them the banner of her art and her iconic image. Perhaps Frida’s ordeal is not unrelated to the fact that she is revered as a saint today. Let us say that both Frida and Tracey, both emblems of survival, were able to transform the Christian combination of martyrdom and adoration into a cultural model of resilience, certainly pop but above all secular and relevant.

With a quiet confidence, with the moving naturalness, confidence and charisma of a great artist, Tracey spoke to us in Florence as having returned from the future. A future in which the whole package of cognitive resources has been rehabilitated and reintegrated by all. Cognitive resources such as love, empathy, care and kindness, tolerance and understanding, sedated by consumerism and never really re-actualized by the Church but rather propagated in the form of oratory, monotonous rhetoric. Love is acquired, acquired by practice, like a language, the language with which Tracey spoke at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence for her first institutional solo exhibition in Italy, before an audience of journalists unaware that they were actually being sermonized and converted by the contemporary papess of vulnerability.

But how do we speak love? Well, we speak it when we confide in each other, when we declare ourselves, no matter to whom, whether to our son, brother, friend, colleague or future spouse. When we speak sincerely, without irony, without any form of aggression, in a disinterested, engaging, authentic, subjective and vulnerable way, exposing ourselves, revealing ourselves with compassion toward others and ourselves. That’s why Christianity has the greatest affective arsenal: the rite of confession, forgiveness, sermons, Mass, jubilees-if it weren’t all so bureaucratized, from the faithful to the priestly employees to the cardinal Ceos, the Church would be at the forefront of affective administration on the planet. Monotheisms have failed to convert us to love, but today Tracey and a few prophets like her speak the language we all know and should speak. We should all speak to each other following the principles of the declaration of love and in every context. Sort of like what happened in the literary language revolutions of the Middle Ages from Latin to the vernacular languages, that is, contaminating every form of artificial language with natural language.

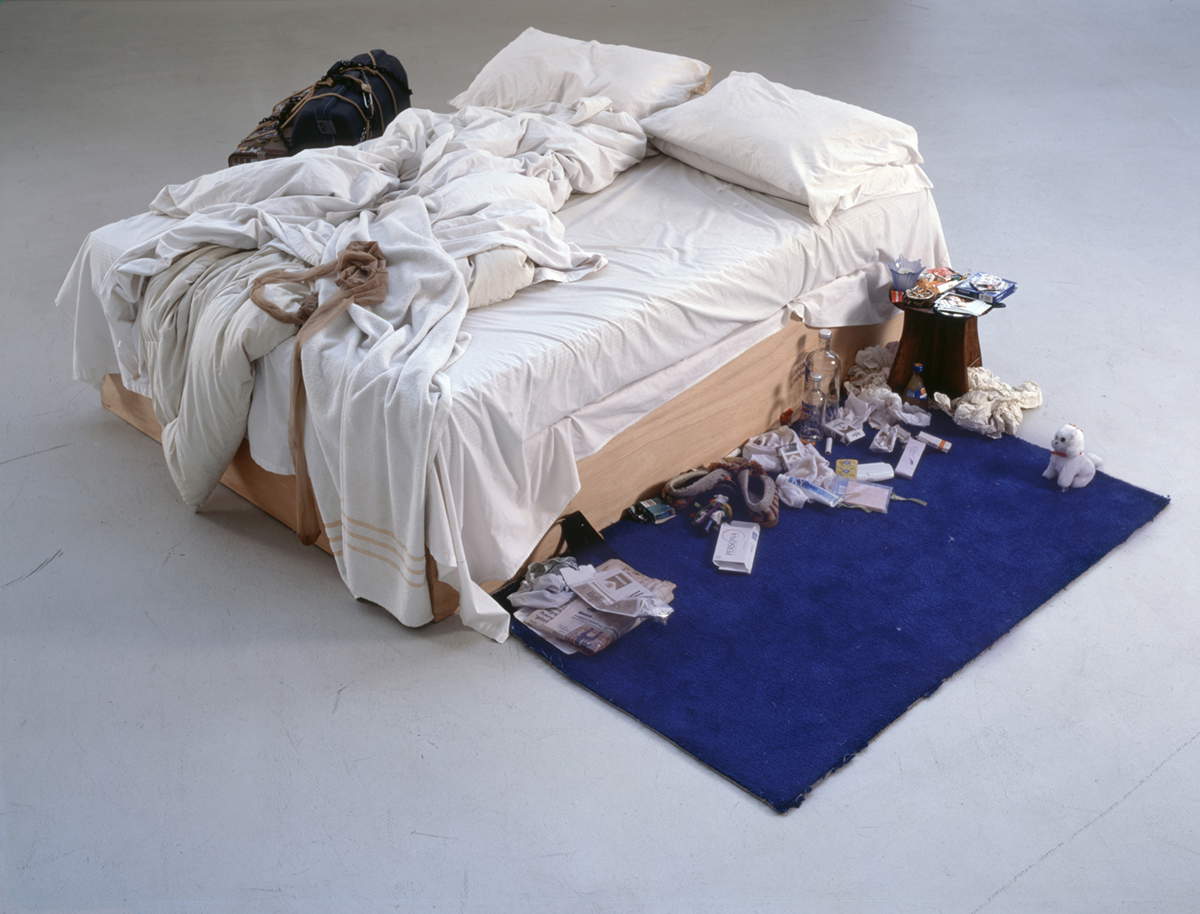

Even when she is not talking about bladder catheters or her cats, Tracey is always confiding, publicly telling her story by bringing attention back to the need for intimacy even in formal and political contexts such as the press conference at Palazzo Strozzi on March 13 among mayors, patrons and various administrators. Removing all affectations and barriers, but without abolishing the limits of morality, in order to sanitize public res, to restore the social function of attachment, the sense of trust and belonging, the basis of life: it is what embodies his most famous work My Bed of 1998, sold in 2014 for $3 million by Charles Saatchi (patron of the entire Young British Artists group including Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas his benchmates) who had bought it for only £150,000, to Count Christian Duerckheim. Loaned after Christie’s auction to the Tate for ten years, it was theoretically to be returned to the German count and collector this year, but the Tate Modern has just announced that there will be a major exhibition to mark the 30th birthday of his artistic career on Tracey Emin in February 2026, and under theimage of My Bed-a workhorse of the Tate whose inalienable property it would be appropriate to somehow become-now the caption reads long loan, the loan has thus become of indefinite duration. That’s something, and hopefully that will be the chance to see it live.

You may wonder what makes My Bed a national treasure: an unmade and dirty bed, laced with empty alcohol bottles, cigarette butts, nylons, used tampons and condoms, old Polaroids, that has become a symbol of depression and its derivatives, transcending with its intimism the exhibitionism, the forcings and in some ways the emulation and corruption of much scandalous and fashionable art a la Marc Quinn or Maurizio Cattelan. The only notable difference between Tracey Emin’s bed and all other provocative or so-called irreverent works is that the bed is hers, a no small detail that distinguishes and legitimizes it as an intimate and original work. It is all in the pronoun my in the title of the work: each residue, besides being each potential DNA sample, certifies its authenticity in the proper and figurative sense. Each of these residues also testifies to the inclusion and scientific theoretical prediction in the work of the whole array of symptoms included in depression. All the drifts and forms of depression ranging from alcoholism to suicide are represented, predicted, and thus theorized, in Tracey’s Bed. A masterpiece in its own right, only twenty-seven years old and undoubtedly one of the rare cornerstones of recent Art History.

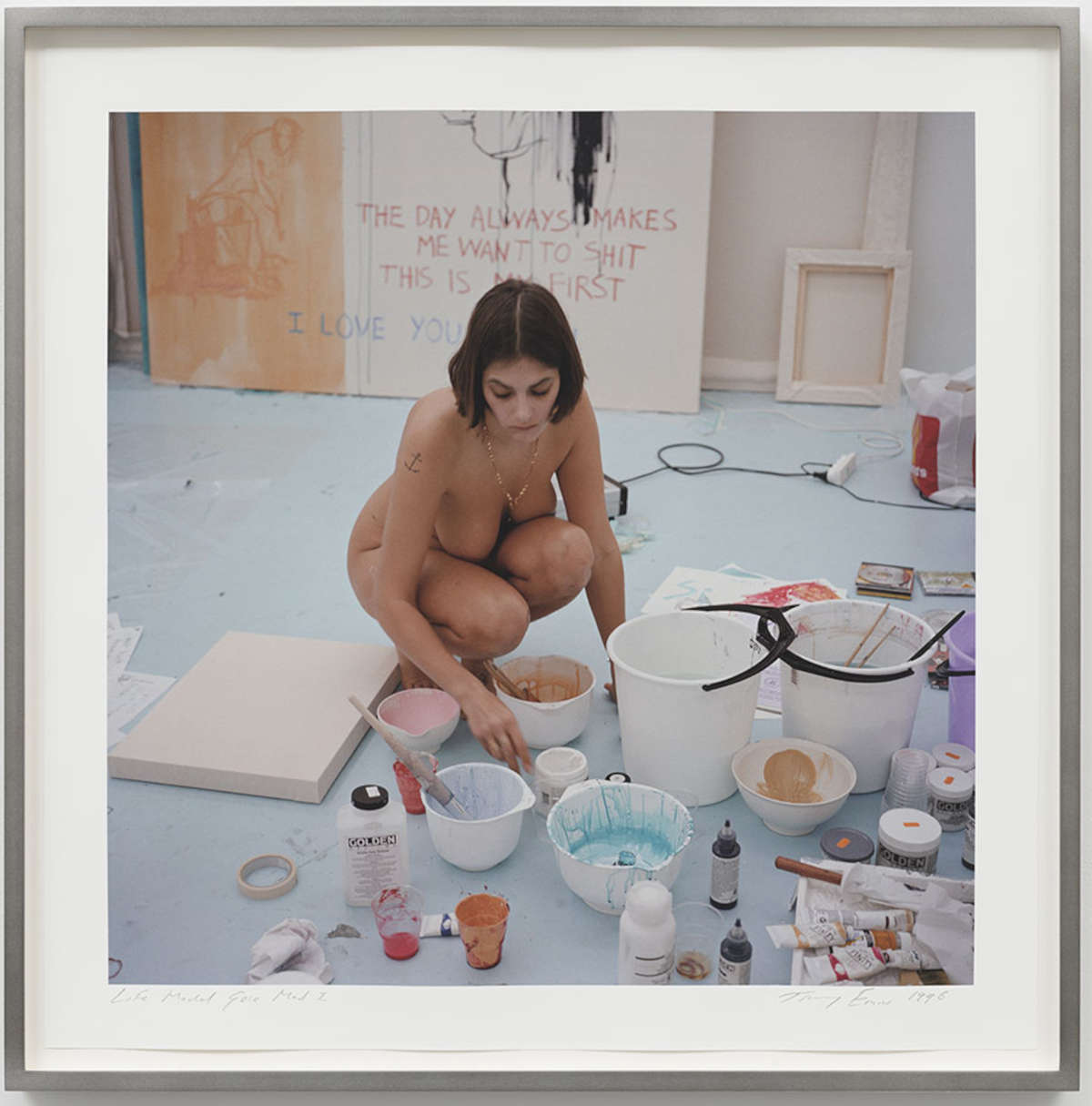

Also belonging to Saatchi, Palazzo Strozzi is repurposing a reproduction of the installation from the 1996 action Exorcism of the Last Painting, in which in a trashy ode to painting, abandoned after two miscarriages, the artist attempts a painful ritualized catharsis by locking herself naked in the Stockholm museum for three weeks, the time between menstrual cycles. A female version of Joseph Beuys’ famous performance and the coyote, as she herself will declare, in which she retraces the subject of the female nude as painted by masters from Munch to Picasso to Klein.

Imposing in Palazzo Strozzi’s courtyard is a monumental replica of Emin’s bronze crouching female nudes that wink at De Kooning’s female bronzes but seen from the opposite perspective. A chance to see that the British artist applies Fontana’s spatialism, lending her own touch of driven sincerity to the female sexes already more blissful than Courbet’s L’origine du monde, all strictly with the hole. Plus large-scale embroidered amplexes and female onanism that defy puritanism, refresh world iconography and contribute to sex education and the end of patriarchy.

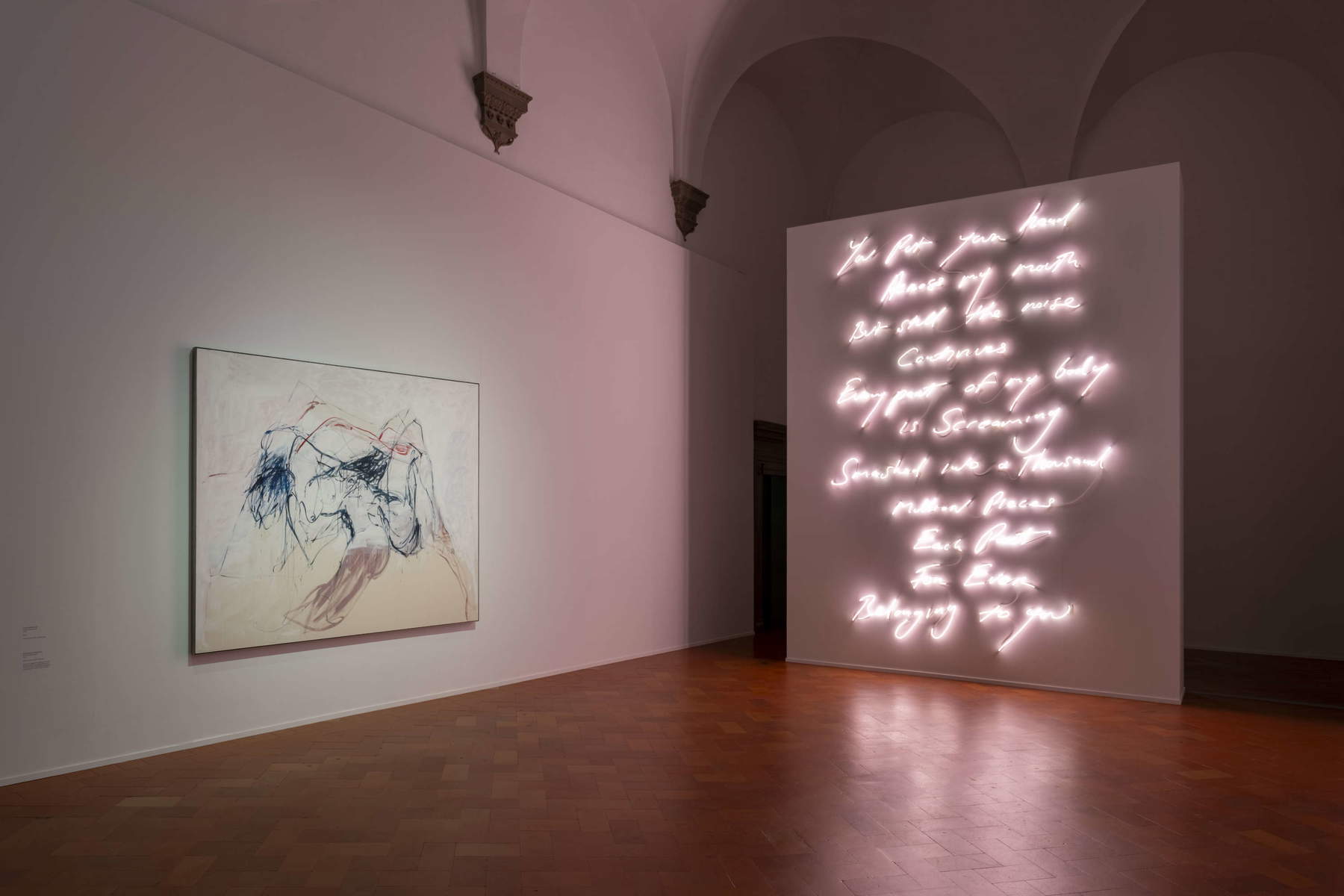

Also in bronze is a love letter that is difficult to decipher but so be it, an attempt nonetheless to transcend gender. A pink neon love poem as high as the ceiling of Palazzo Strozzi, love fragments on handkerchiefs and other textile works that combined with her entire corpus of love neons constitute a manifesto of affective aesthetics that only today Tracey acknowledges that she did not quite realize she had to distinguish from gender. So it remains a missed opportunity and a regret that instead of the neon, albeit made site-specific and giving the exhibition its title, Sex And Solitude, Tracey did not instead adorn the facade of Palazzo Strozzi, giving it to Italy and thus to the History of Art, as she did on other public occasions by somehow blessing Downing Street and St. Pancras Station with one of her consecrating declarations of love. Too bad.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.