Why Helen Frankenthaler's painting was "without rules." What the Florence exhibition looks like

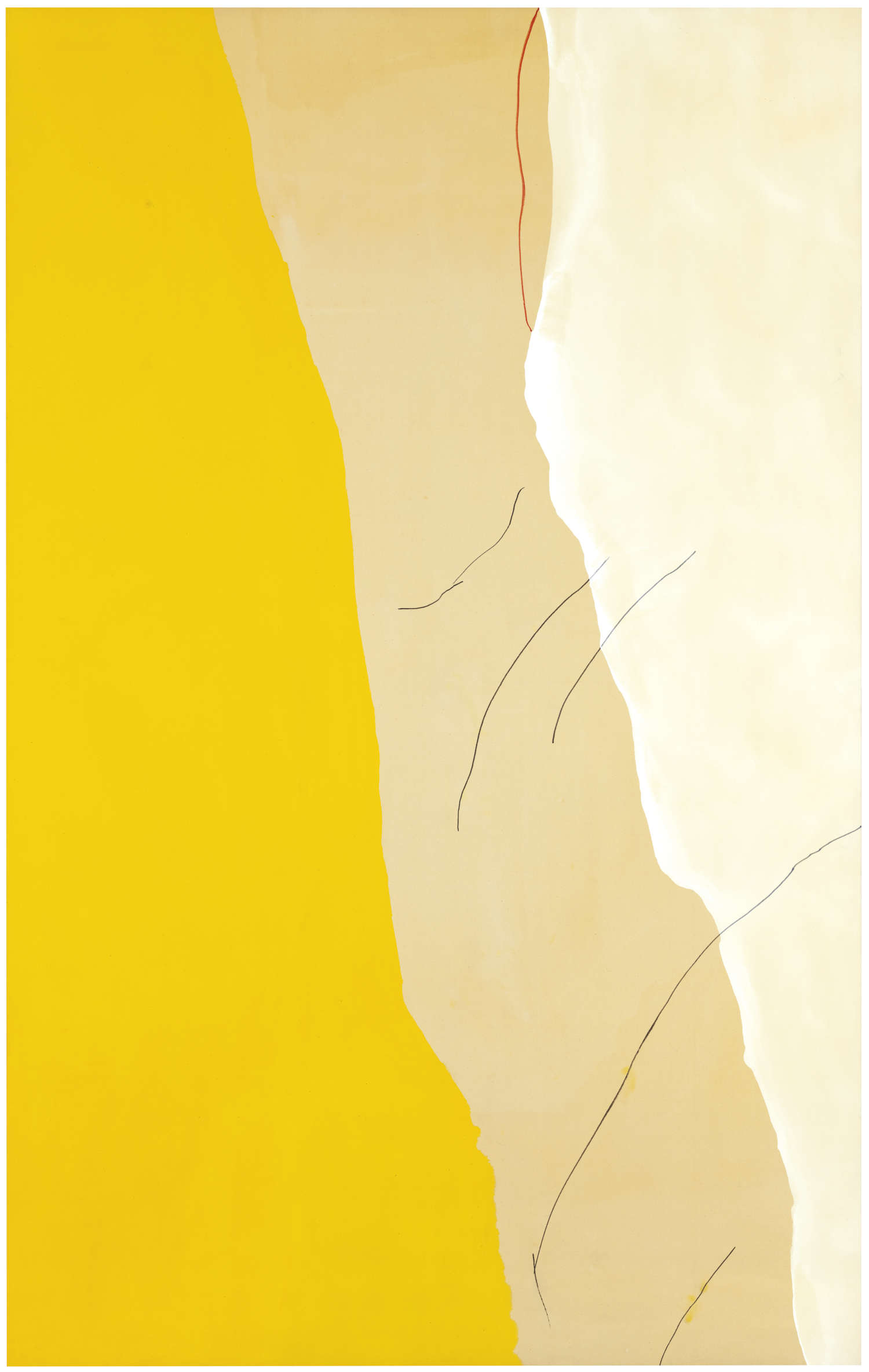

The most poetic and coldest painting at the same time on display at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence (through Jan. 26) in the exhibition Helen Frankenthaler. Painting Without Rules, is titled Mornings and dates from 1971. The American painter was 43 years old and had already gone through some moments, let’s call them that, where her painting brought to the surface a kind of friendly bond each time with “abstract” artists whose certain linguistic inventions she had transposed. The painting has vertical backgrounds of first intense yellow and then gradually lighter and drier, in two other layers, crossed by black filaments. A painting quite different from others of the period, though not unique.

Helen’s painting in the early 1950s took into account Pollock’s graphic cosmic totemism, seeking at the edges of her own colored forms that “contour” which gave them a plastic, almost sculptural substance without trespassing on three-dimensionality. But there was not only Pollock: the painter entered within the radius of influence of the “Irascible” painters who, with Pollock, formed the so-called New York School, exhibited in Milan a decade ago: Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Franz Kline and several others.

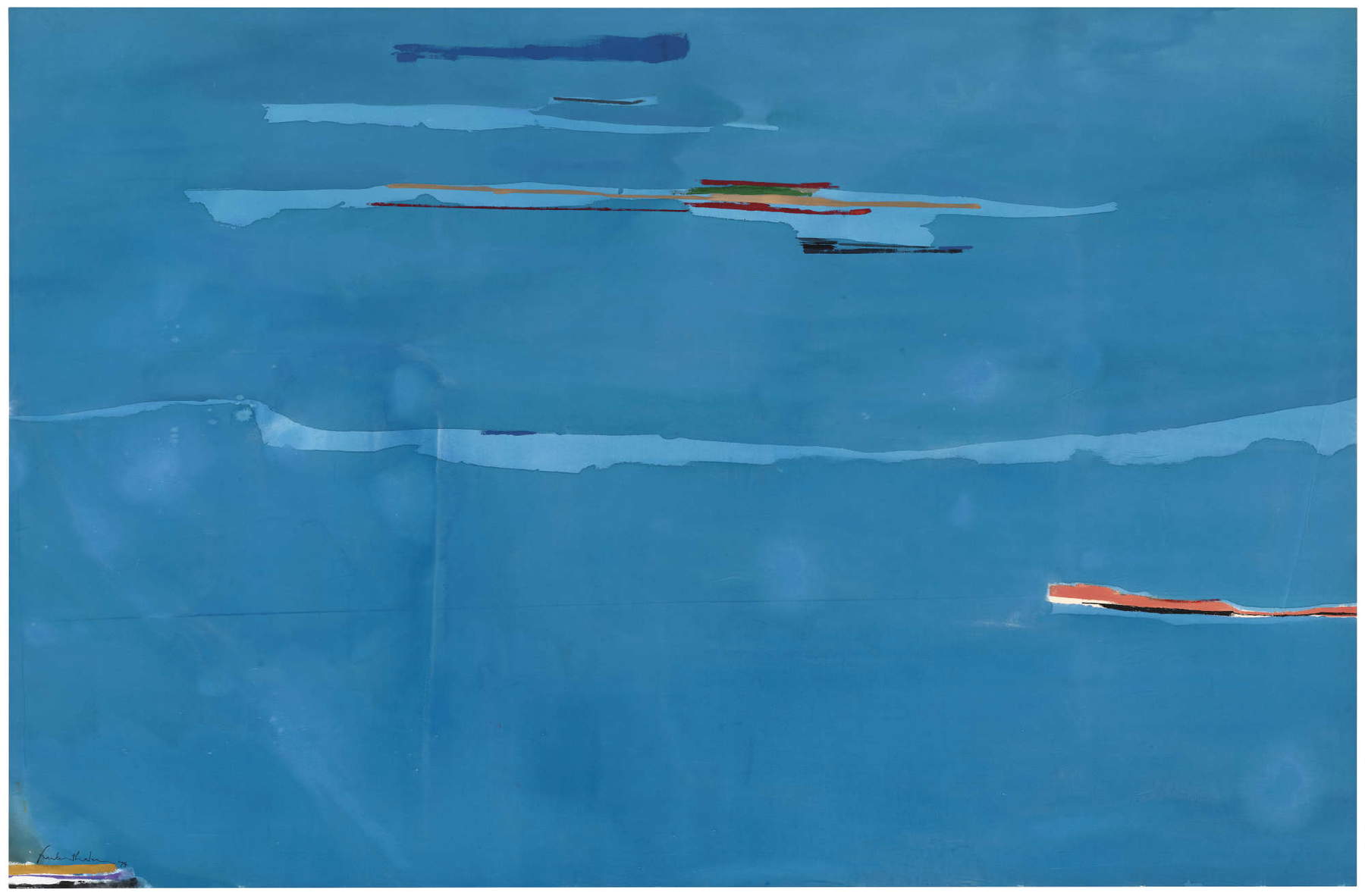

The following decade, the 1960s, decreed the success of Pop Art as a fetish of consumer society. An art that Frankenthaler’s “contemplative” dimension hardly seems to see. The maximum allowed is to measure himself against the abstract but charged with constructive and, in some respects, postfigurative values sculpture of David Smith with whom he had a deep and lasting friendship since the Postwar period. Penetrating instead into Helen’s gaze is the transcendent nebula of layered rectangular forms that made Mark Rothko universally famous, absorbing masses of sublimated color that never attains pure abstraction; and for that matter, this is explained when one thinks of the Jewish roots of the Latvian-born American painter, who would take his own life in 1970. Rothko seems to be revealing to Helen the secret of irregular forms that float on the edge of ambiguity because they are abstract and at the same time suggest a “beyond” that has to do with mysticism (in Cape - Provincetown of 1964 Frankenthaler creates a composition of color-masses in dense blue tonal succession that end in an almost surreal form and at the base have two green and yellow bands. Is there something symbolic about these compositions, or must we surrender to the idea that this color of Helen has something ontologically feminine about it?).

With her husband, Robert Motherwell, Helen makes up an association that began in the late 1950s when the two met in Leo Castelli’s Gallery - the architect of the fortunes of both the protagonists of Abstract Expressionism and certain exponents of Pop Art. Helen, however, always maintains her autonomy, which is also, as Douglas Dreishpoon writes in the catalog (Marsilio arte), her own particular form of ambiguity. It is about the way in which the painter relates to space, which finds in artists such as David Smith, Anne Truitt and Anthony Caro a relationship of friendship and mutual artistic confessions that lasts for decades and has left traces in a conspicuous correspondence between them of which a good selection of letters is published for the first time in the catalog, illuminating a fundamental point: between Frankenthaler’s painting and her correspondence exchanges there is an existential relationship. Mind you, it is not just a matter of intimist tales, of human experiences, of episodes that happened from which his painting draws nourishment as emotion; on the contrary, that painting, in its varied formal expression, is the background onto which the artist’s life is projected. But the essential fact, without in any way detracting from the amicable relationship-they are generally all artists who share a research on art where each reaches his own figure with full freedom: Frankenthaler’s slogan, chosen as the title of this exhibition, is: “without rules,” of which we must always make a critical analysis if we want to understand what the artist means-the center of this story is always and in any case painting.

Since we have mentioned it, let us go a little deeper into the meaning of “without rules.” If we look closely, we will hardly confuse Frankenthaler’s painting with that of his “masters” or with the language of his sculptor friends. The effort to maintain this connection without being subject to it is precisely the full freedom of ideas and action. One must consider that in the late 1940s and 1950s, abstractionism became the gospel of American painting. It is useful to remember that a conceptual phenomenon such as Duchamp’s began to emerge on the scene in the 1950s precisely because of American collecting (where he was also active as a new art guru: it was he, for example, who became the go-between as early as 1926 in the Costantin Brancusi exhibition in New York City, which triggered an international case because a customs officer treated Bird in Space as an ordinary household utensil, and thus subjected it to taxation rather than considering it a work of art. This generated a trial that for the first time brought abstractionism to the bar, so to speak).

In France where today there is even an annual Duchamp Prize (which usually selects artists and works that have inherited very little of Marcel’s genius), until 1977 he was almost ignored, and the first retrospective was dedicated to him that year at the opening of the Beaubourg, instigated by Pontus Hulten, the director in pectore, and curated by Jean Clair, who produced no less than three tomes of a catalog. All this is to say that abstractionism was first and foremost the American artistic novelty of the postwar period, indeed it was a kind of secret weapon in what has been called “The Cultural Cold War,” when it was discovered now three decades ago that from the 1950s onward the CIA sponsored American abstract artists-Pollock, De Kooning, Rothko, etc. - contrasting their aesthetic strength with that of Soviet socialist realism painters. While abstractionism was just beginning to spread in America in the 1930s, at the same time, just in and around New York City, a congerie of realist painters dominated who were by no means to be trifled with and who echoed the story of the Yankee pioneers. So when we look at Frankenthaler, we have to think that although abstractionism was an imported value from Europe, in America it became an elitist avant-garde form, shall we say, that sought to make art an international idiom of creative freedom. Which should not obscure how much this idea accompanied the magnificent and progressive fortunes of American capitalism. With these premises, the CIA-Soviet opposition also found a cultural battleground that seemed to pit modernists and reactionaries against each other.

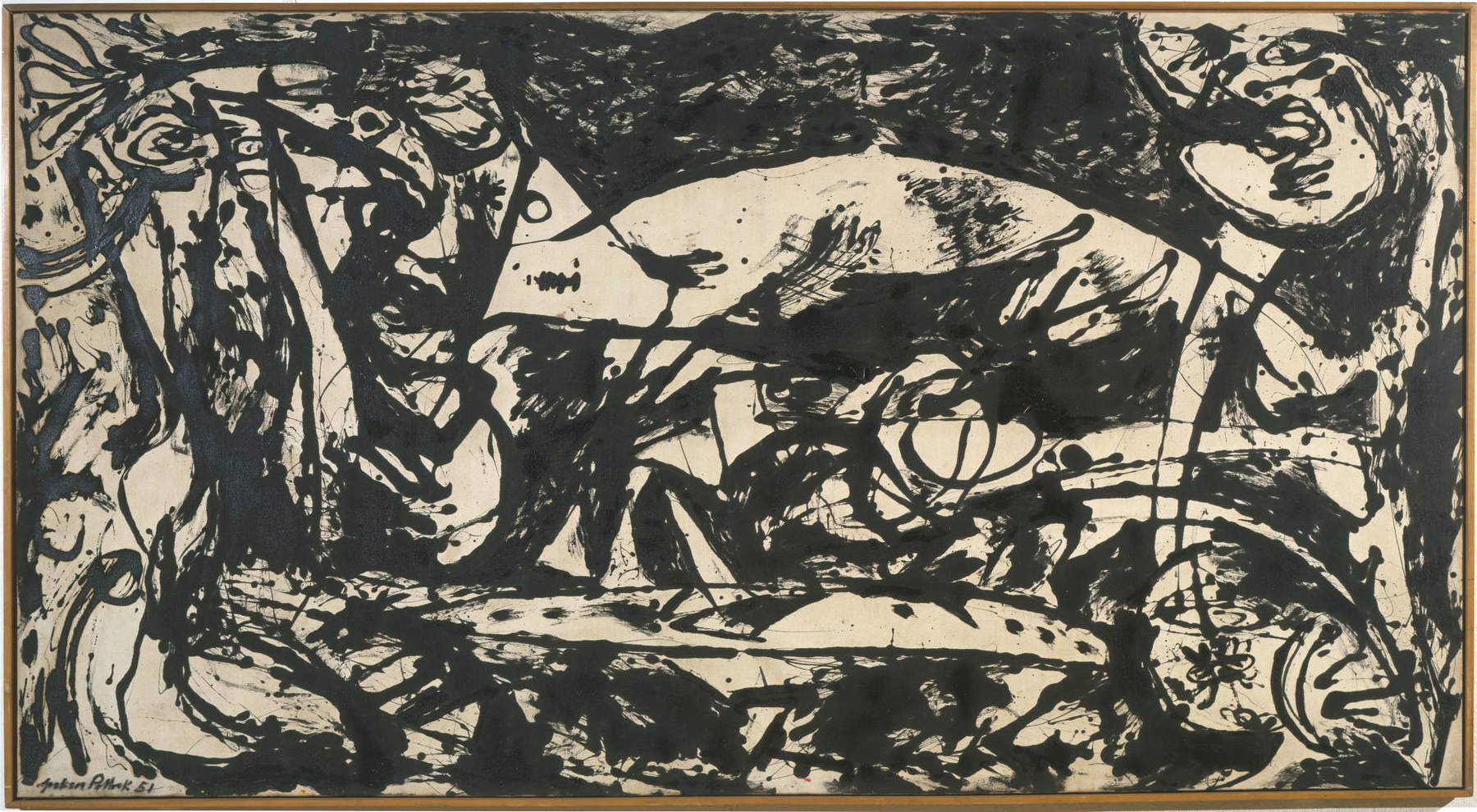

When Frankenthaler says “no rules,” she is in some ways taking up the bet that had been taken in the immediate postwar period by her predecessors of about a generation, Rothko and Pollock precisely, who in the aftermath of the war openly embraced abstractionism after pondering primitivism, figuration and surrealism. The discourse recedes another abundant generation when one considers that one of the first painters torn between European expressionism and abstract impulses was Mardsen Hartley, Pollock’s teacher, who in the 1910s was in Europe where at the turn of the Great War he elaborated paintings of a symbolic, totemic and abstract character, a magical-esoteric expressionism from which he then took the road that would be traveled by American abstract expressionism, the bearer of substantial archaic reminiscences derived from the crossroads with indigenous cultures of centuries before, which left “Warburgianly” mnestic traces on the American psyche. On the level of phenomenology it is a middle path, so to speak, between a suspicion of partially figurative language and an essentially abstract valence of form-color, which we also find in Frankenthaler. We could follow it in abstract paintings such as Open Wall (1953), Western Dream (1957) or Mediterranean Thoughts (1960)-where the memory of certain things by Hartley seems almost to re-emerge in a watermark-but then, in addition to Cape, already mentioned, Tutti-frutti (1966), Blue Mobile and Fiesta (1973), Plexus (1976) Madrid (1984), Janus (1990), The Progress of the Rake (1991), the extraordinary acrylic canvas Maelstrom of 1992, which turns to white an informality remotely indebted to Pollock’s cosmic feeling, and finally Solar Plant (1995). I wanted to mention these paintings below without too much comment because these are works to look at and compulse, avoiding seeking explanations in “representational” meanings. It is the color itself that speaks, in the forms in which it is painted. A crossing of the threshold of anagraphic age, the curator writes, to enter of the color that reveals a new reality (I do not know if over time the best remains, as he writes, personally it seems to me that Frankenthaler’s best lies between the 1970s and 1980s).

And this brings us to the second theme that emerges when looking at Frankenthaler’s paintings. It is, and should not be understood as a diminution, of women’s painting. Douglas Dreishpoon calls the painter a “reluctant feminist,” and it is not difficult to agree, because, as the critic writes, her painting poses essentially aesthetic questions. It is a feeling in depth. Critic Barbara Rose, for example, had an anxious experience after seeing a painting of Helen’s from the 1950s in 1970 that left her “torn” when she saw the figure 173 in the upper right-hand corner. Indeed, she remembered a meeting at the Frankenthaler-Motherwell home before Barbara divorced Frank Stella, and since the two painters lived at 173 East 94th Street, that number sadly reminded her of happy days with her ex-husband. This, moreover, stirs a sediment of life beyond the painting itself: it is almost parapsychology. Frankenthaler, on the other hand, makes us realize that a woman’s painting is different from a man’s precisely in structural valence: Because a woman painter hardly considers the painting a threshold between figurative-abstract or between form-inform; the canvas, without wanting to give the expression a sense of mirroring with the maternal condition of women, is like a cosmic nebula where space and time contain all forms of life, and only one emerges on the canvas with the content of a “being” made of colors.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.