Who was Boccioni before he became a futurist? A complex artist. What the Parma exhibition is like

The surface changes over time and centuries, but the substance of art remains the same, is immutable, is eternal. Umberto Boccioni realized this shortly after his arrival in Milan in 1907, having just visited the Last Supper and been impressed by Leonardo da Vinci’s shadows on the wall of the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie. “The form varies, the essence is always that.” It is 1907, Milan is a pulsing, modern city, more spirited than Rome, the capital of Italy; it is a city that lives through and faces the crisis of verist painting; it is a city where the last songs of the scapigliatura are now silenced by the divisionist wave of the greats of the time (Previati, Morbelli, Segantini) and all the masters who gravitate around them; it is a city where a perpetually restless, dissatisfied, and tormented Boccioni felt most acutely the need, on the eve of his Futurist turn, for a modern art, an art capable of overcoming that “sentimental” which he despised (“sentimental” was an adjective he used almost as an insult, in his notes) and which he had, however, found in much of what he had seen at the Venice Biennale that year. Boccioni had been all too sharp, in his crusade “against the old romantic, veristic, symbolic junk, against all technical superficialism, against all intentional sentimentality.” To better understand then the transition between before and after, between the “prefuturist” Boccioni, as per the title of an exhibition whose fortieth anniversary falls this year, and the futurist Boccioni, it is necessary to see him at work in Milan. And the Milanese prefuturist Boccioni is the culmination of the exhibition Boccioni before Futurism. Works 1902-1910, which is being held at the Magnani Rocca Foundation in Traversetolo: four curators (Virginia Baradel, Niccolò D’Agati, Francesco Parisi and Stefano Roffi) to retrace the first phase of Boccioni’s career, the lesser-known, the most erratic, the least mentioned, the most troubled.

Between the reconnaissance of the prefuturist Boccioni that was carried out in 1983 by Maurizio Calvesi and Ester Coen and the exhibition at the Magnani Rocca forty years have passed during which studies on Boccioni have marked several novelties, especially with regard to Boccioni’s frequentations, particularly in the Roman period: “in order to provide an unprecedented key to Boccioni’s works,” the curators explain, “it is still indispensable to enter inside the expressive code that united the artist with his contemporaries, helping to unveil certain of his modes of operation and the processes of his inspiration.” This is the main reason for the interest of the exhibition at the Magnani Rocca: to observe Boccioni within his own context, to see him face to face with the artists he appreciated, with whom he frequented, and with whom he exchanged ideas, opinions, and opinions, within the framework of a precise reconstruction that follows with great care the first, uncertain and difficult steps of the artist born in Reggio Calabria. A tour itinerary that has almost two hundred works, including paintings, drawings and engravings, and that may perhaps be a little difficult for those who are not very familiar with the art of the late nineteenth century, but Boccioni’s complex and heterogeneous itinerary in these crucial years for his career, and also for the fate of the Italian avant-garde in the transition between pointillism and futurism, certainly requires a challenging treatment.

The public will get the impression of a Boccioni who is not always able to fully express what is outlined in his mind, the impression of a suffered path, even physically: it is a man who appears to us as a desperate Boccioni in financial distress that from Paris, where he moved for some time after leaving Rome, in 1906, he writes some postcards to friends (discovered by Francesco Parisi and published on this occasion) with explicit requests for help. To Giovanni Prini, for example: “Dear Prini since you have been so good as to promise me please send me immediately etc. because I do not know where to turn. Sironi is also not too well off and we help each other. Do not say anything at home.” And then, it will be necessary to consider that, although the futurist Boccioni is the most studied and best known, his “prefuturist” phase occupies a decidedly longer chronological span: the public tends to consider only the last six years of Boccioni’s life, but before that lies the experience of an artist who devoted to his painting a decade of continuous, laborious research that had begun from the time he had taken up holding a pencil, a paintbrush. Arriving in Rome in 1899, he first devoted himself to journalism and then changed his mind and approached drawing and painting in 1900. “I bought myself the pastels, the brushes, the ink and that cue with a ball to lay my arm on, and now I’m going to make my easel. You see that I notice in the midst of artistic life”: so the 19-year-old Boccioni wrote in October 1900 to a friend in Catania. From here, from a purchase of material, we can somewhat romantically make Boccioni’s journey in art begin.

The opening is reserved for illustrations, a production to which Boccioni devoted himself essentially for reasons of practical and economic necessity, although Niccolò D’Agati, in the catalog, warns about the prejudices that affected this area of Boccioni’s corpus, since illusitration “is to be considered a significant moment in the artist’s pictorial research,” since even within the narrow confines of the most commercial art Boccioni demonstrates “a constant updating and comparison with the most significant models of illustration of the time.” His training unravels under the guidance of master Stolz (Alfredo Angelelli), and he looks to modernist models, particularly Munich and Vienna. There is, of course, a production that is more easy, and that wearied Boccioni himself, such as that which looked to English models (postcards with costumed characters or fox-hunting sketches abound in the exhibition, for example, which do nothing more than copy graphics from across the Channel), but the results of some research even in the field of advertising graphics, for example the cover for the Avanti della Domenica with the racing automobile of 1905, which the public immediately finds at the opening of the exhibition, anticipate certain eventful results of the artist Boccioni. The part reserved for illustration is the most substantial in the exhibition and will also return in the last room, to suggest to the visitor that Boccioni continued to practice this activity for several years, mainly for economic reasons. It will be useful to remember that although this area of Boccioni’s production was well known, the material exhibited at the Magnani Rocca has largely been published recently, and this is the first occasion on which so many illustrations are exhibited together.

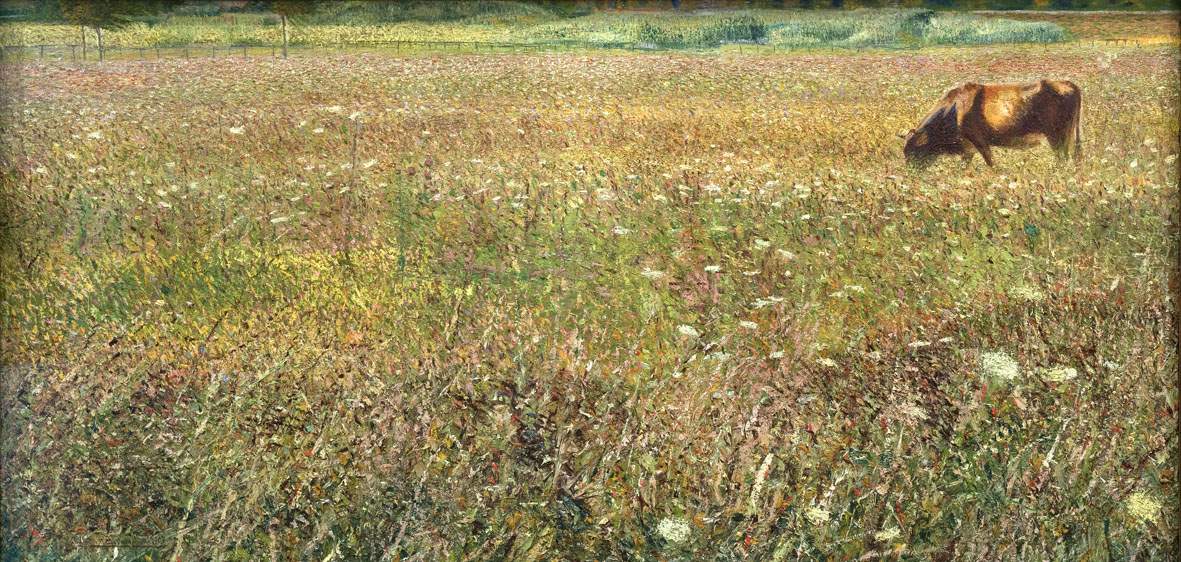

After the introduction devoted to graphic art, the exhibition is basically divided into three sections, curated respectively by Francesco Parisi, Virginia Baradel and Niccolò D’Agati, to which correspond as many rooms, each dedicated to one of the cities of Boccioni’s formation: it begins with Rome, continues with Padua and Venice, and concludes with Milan. The Roman debut is to be identified in the Roman Campagna of 1903, which stands out in the center of the first section of the exhibition and which is fundamental for observing the coordinates along which the very first Boccioni moves: his arrival in the capital brought the artist closer to the milieu of the “Roman bohemianism,” as Gino Severini had defined it, an artistic-literary milieu around which gravitated the crepuscular Sergio Corazzini and Corrado Govoni, both teenagers, and artists such as Mario Sironi, Guido Calori, Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona, Severini himself and others. A coterie that Boccioni soon left, however, to get closer to more mature artists such as Giacomo Balla, Giovanni Prini, and Duilio Cambellotti. It is, in particular, Giacomo Balla who is the young Boccioni’s main point of reference, for it is in Balla that the artist finds a soul that best resonates with his sensibility: already at those heights Boccioni’s intentions were oriented toward a transfiguration of the real datum, not necessarily linked to the expression of an emotion, but if anything subordinated to the “service of a scientific sensibility,” as he himself would explain in 1916. It is therefore in Balla’s works that Boccioni finds the quintessence of modernity, and it is toward Balla that his first tests are oriented: the Campagna romana should therefore be read as Boccioni’s first mature work, which in the exhibition finds its ideal correspondence, for example, in Giacomo Balla’s Veduta di Villa Borghese dal balcone, a painting in which a vast green expanse, with a high horizon near the upper edge of the canvas, becomes the occasion for an intense experimentalism on the alternations of light and shadow. Balla tries his hand at a vespertine view, while Boccioni’s countryside is taken in the afternoon, but the intent is similar, as is the technique of short, stringy brushstrokes, which most of the Divisionists share (observe, at a short distance, Enrico Lionne’s Red and Green and Giovanni Battista Crema’s Piazza dell’Esedra at night ). Roberto Basilici, on the other hand, departs from it, and in the exhibition he is placed side by side with Boccioni’s Campagna romana because of similarities in subject matter (there is not even a missing ox striding through the grass) and differences in execution, with Basilici proceeding by juxtapositions of colors and still retaining traces of the sentimentalism that Boccioni would have so detested.

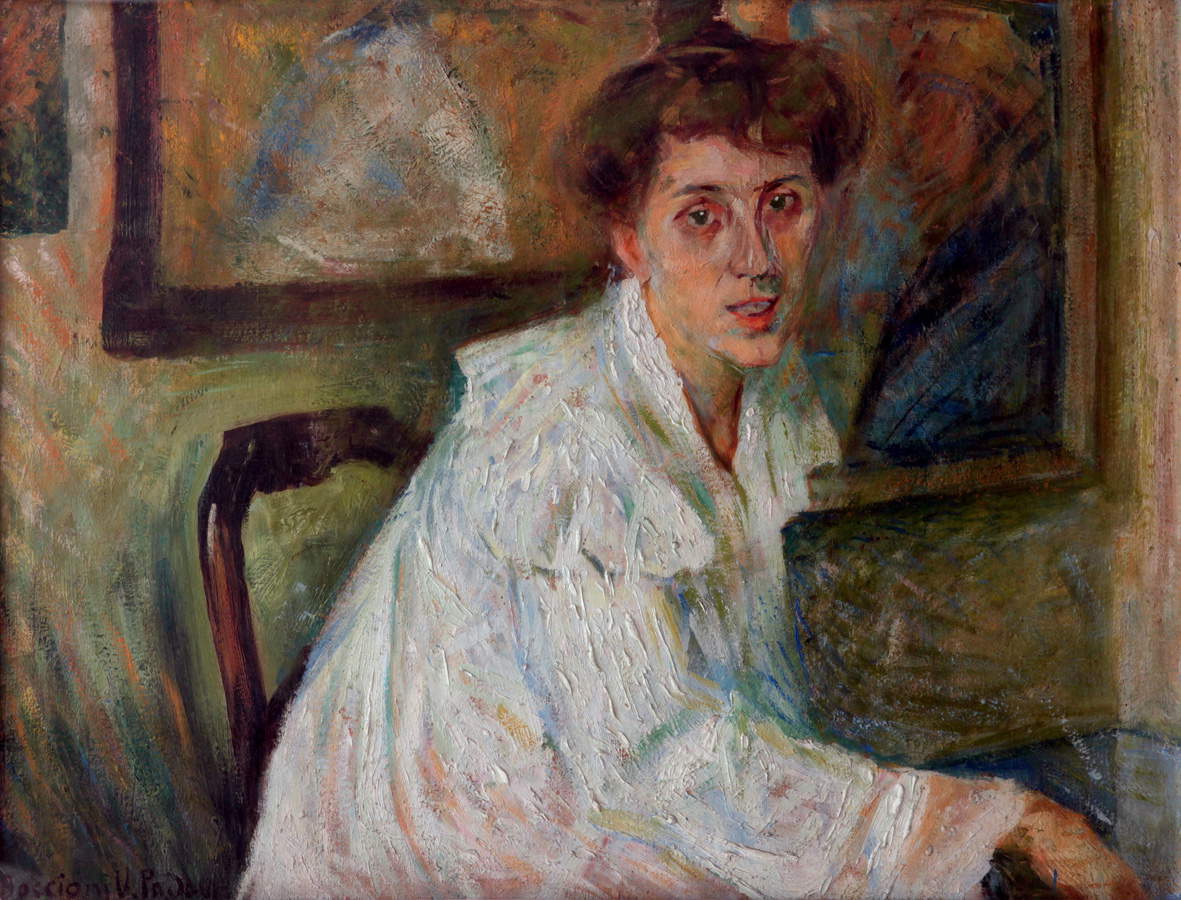

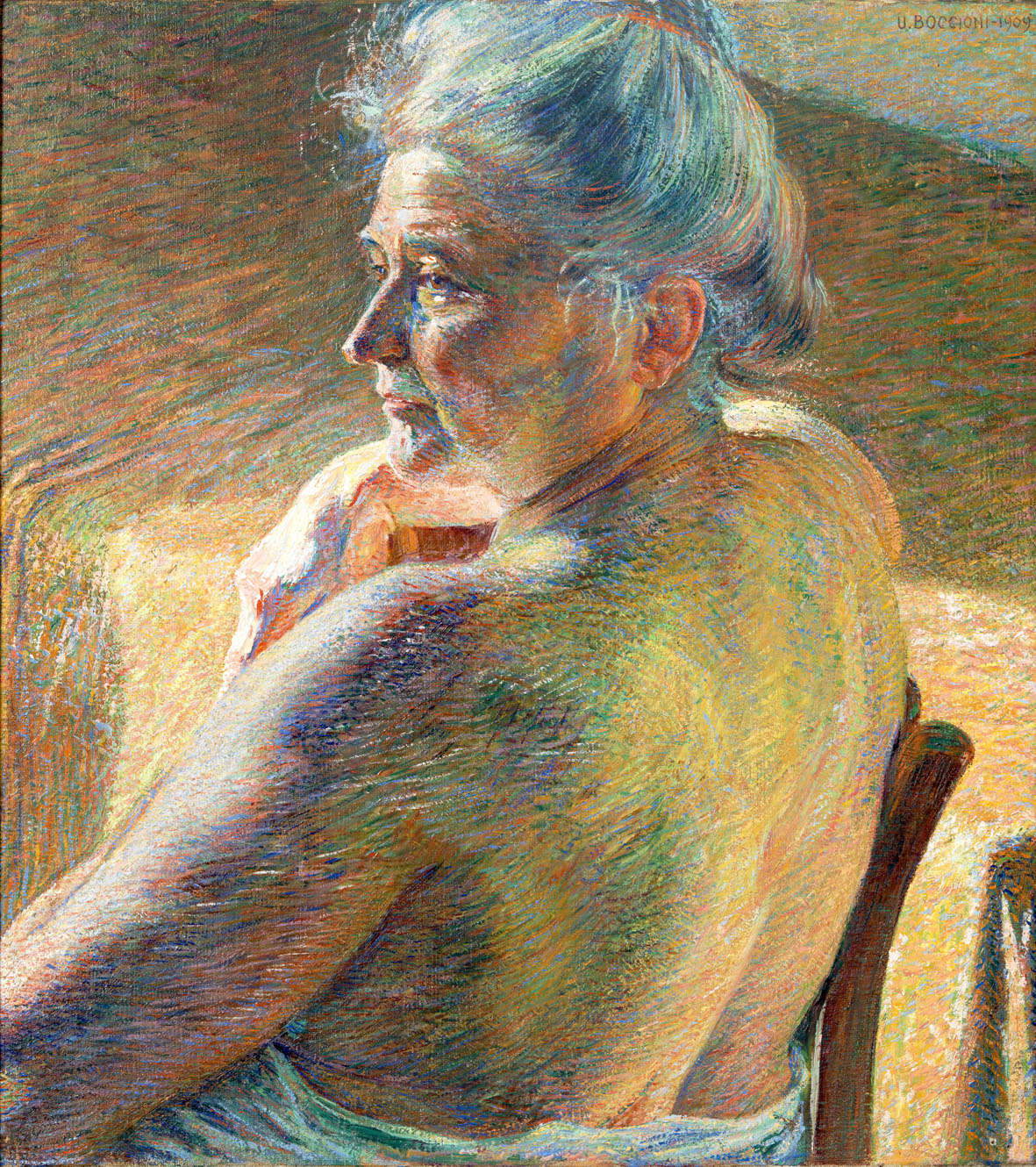

The chapter edited by Francesco Parisi then includes a solid subsection devoted to portraiture, a diriment strand in Boccioni’s research. The framework is provided by an intense Portrait of his fiancée Orazia BelsitoA self-portrait of Sironi in his twenties that declare his dependence on the manners of Balla (who would later, as is well known, become, just like Boccioni, one of the leading names in Futurism): an early evidence of Boccioni, in this sense, is the Female Portrait of 1903 also strongly linked to the manner of the master, as well as the later Portrait of a Young Man and as the Portrait of Mrs. Virginia, executed in Paris in 1906 but still dependent on Balla’s lesson, although a less indulgent attitude towards the realistic datum is beginning to be observed. If anything, his detachment from Balla is substantiated, the curator writes, in a “more simplifying and essential line often interrupted by the violent and dynamic creative impulse of the pastel or brushstroke that restored a new quality to the work without aestheticizing aims,” and in a pointillism that dilutes the natural by going more in the direction of the explication of a state of mind, in accordance with the most up-to-date movements of European art of the early twentieth century.

The section on the Venetian Boccioni is opened by another early work, January in Padua, contemporary with Roman Campagna and thus animated by the same intentions (the artist spent much of his childhood and adolescence in Padua, and would return there several times, eventually settling here upon his return from trips to Paris and Russia in 1906). And the same is true of certain canvases painted in Padua, such as the Cloister and the Portrait of the Sister in Ca’ Pesaro, which, if they reveal some differences with respect to the paintings executed during the same period in Rome, do so above all in attitude: Padua, a city of childhood memories, probably inspired Boccioni with paintings in a more reflective and intimist vein. The Padua sojourn of 1907, however, marks a significant stage in Boccioni’s career, as Ester Coen already noted in 1985, writing that “the works painted during this period bear the mark” of a new “research above all on color, which the artist exasperates by playing on tonal juxtapositions” and a “search for spatiality by forcing the contrast between figure and background.” Exemplary in this sense is the Ritratto del cavalier Tramello, a superb portrait where “a bundle of strokes divided by contrasting colors swarms over the background, while behind the head, where the course curves and the palette appears more dense and colorful, alluding to the back of an armchair, seems to become a halo of the shape of the head itself” (so Virginia Baradel), exhibiting one of the most modern pinnacles of the prefuturist Boccioni, a Boccioni who marks perhaps the point of maximum detachment from what he had learned so far. The rest of the Padua section focuses on the artists Boccioni got to see at the 1907 Venice Biennale: among the few who will get a favorable judgment from him are Gennaro Favai, for his ability to evoke the suggestion of a state of mind through a view, to touch the soul of the things he observes (a similar role will be recognized, on the occasion of the same Biennale, by Vittorio Pica to Mario De Maria, who was also present in the exhibition, although with a figure work and not a landscape, namely I monaci dalle occhiaie vuote, a painting also exhibited at the 1907 Biennale). However, Boccioni, as anticipated, was decidedly rigid about what his colleagues were exhibiting in that edition of the Venetian exhibition: he was not thrilled by Guido Marussig (who was present at the Magnani Rocca with a dreamy Laghetto dei salici, not exhibited at the 1907 Biennial but close to what the Triestine artist had the opportunity to present on that occasion), nor was he convinced by Plinio Nomellini, who brought to the lagoon his famous Garibaldi now at the Fattori Museum in Livorno. Nomellini seemed weaker to him than a Previati, an artist in whose regard Boccioni felt boundless admiration: and it was precisely with Previati, as well as with Segantini, that Boccioni had the opportunity to measure himself in Milan, where he arrived at the end of 1907, and where the Magnani Rocca exhibition ended.

As early as 1965 Ragghianti, in his article Boccioni prefuturista published that year in the magazine Critica d’arte, identified the two “poles” of Boccioni’s art in Previati and Segantini, although initially the link with the work of Balla was not lost, of whose work the famous Self-portrait of 1908 in which Boccioni depicts himself as a colbacco, still recalling his recent trip to Russia. In contact with Lombard Divisionism and Milan in general, however, Boccioni was a profoundly renewed painter, a conscious artist (“I feel that I want to paint the new, the fruit of our industrial time. I am nauseated by old walls, old buildings, old motifs of reminiscences: I want to have my eye on the life of today,” he wrote as early as March 1907), an artist who, faced with the dilemma posed to him by contact with modern painting (as Calvesi noted, the alternatives were a couple: “to seek the ’new’ ideality and the ’new’ universality of art in the contemplation, or idealization, of the modern world, with its rhythms of production, its very artificiality, its very scientificity, its linear mathematicality”, or “reviving the eternal poetry of Nature, of the ’Great Mother’”), he chooses to address it not so much on the level of content, or at least not only on that, but rather on the level of what he would call “positive idealism” the definitive overcoming of the natural datum, of objective description, of verism in the direction of an aesthetic aimed at expressing a thought, a state of mind through the linguistic means of painting. Hence the landscape paintings produced in Milan tend, writes Niccolò D’Agati, toward “a painting in which the true finds its resolution in the idea,” are translated into views in which one appreciates “an unprecedented accentuation of the properly pictorial values, of that decorative sense, in the aspiration to the ’grandiose, symphonic, synthetic, abstract.’” In the exhibition, the signs of these disturbances can be seen, for example, in a 1908 Casolare, which is placed in direct comparison with a small but surprising Landscape by Benvenuto Benvenuti, a pupil of Vittore Grubicy and among the most visionary of the Divisionist group, as well as, in the absence of analogous paintings by Segantini, with a pair of mountain views by Carrà and Erba, and with a strongly evocative painting, Fireflies by Leonardo Dudreville, who like Boccioni went through a troubled period that would later lead him to approach Futurism. Equally interesting is the Campagna con contadino al lavoro (Countryside with Peasant at Work), exhibited alongside his preparatory drawing, a work that marks one of Boccioni’s greatest points of rapprochement with Segantini.

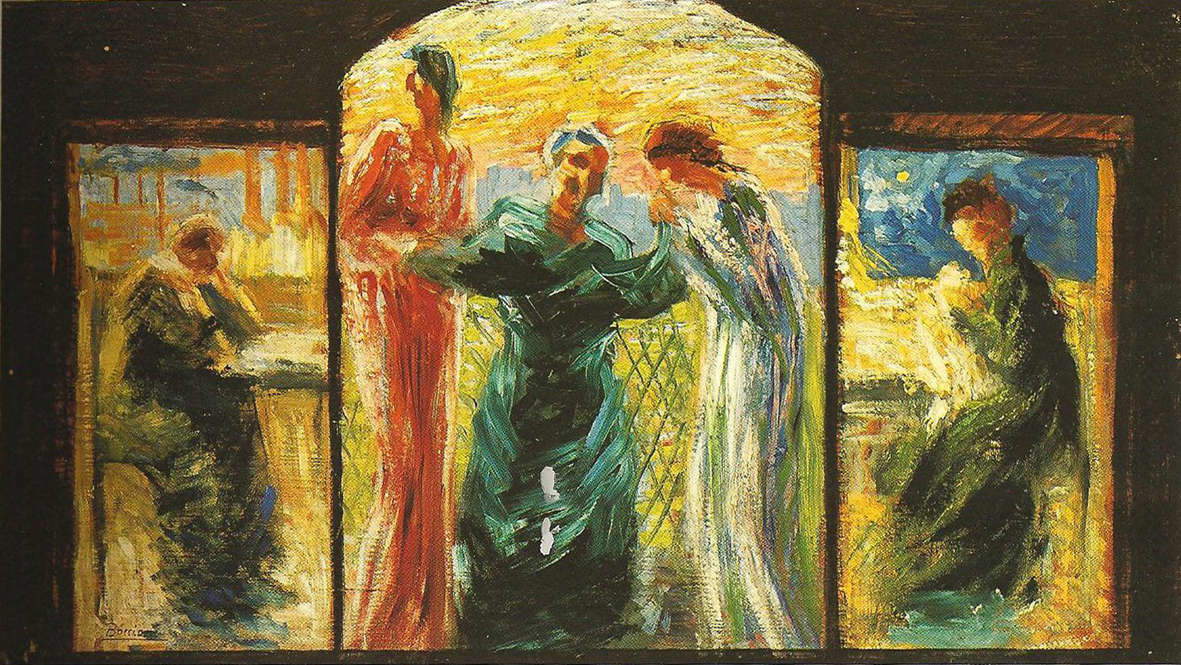

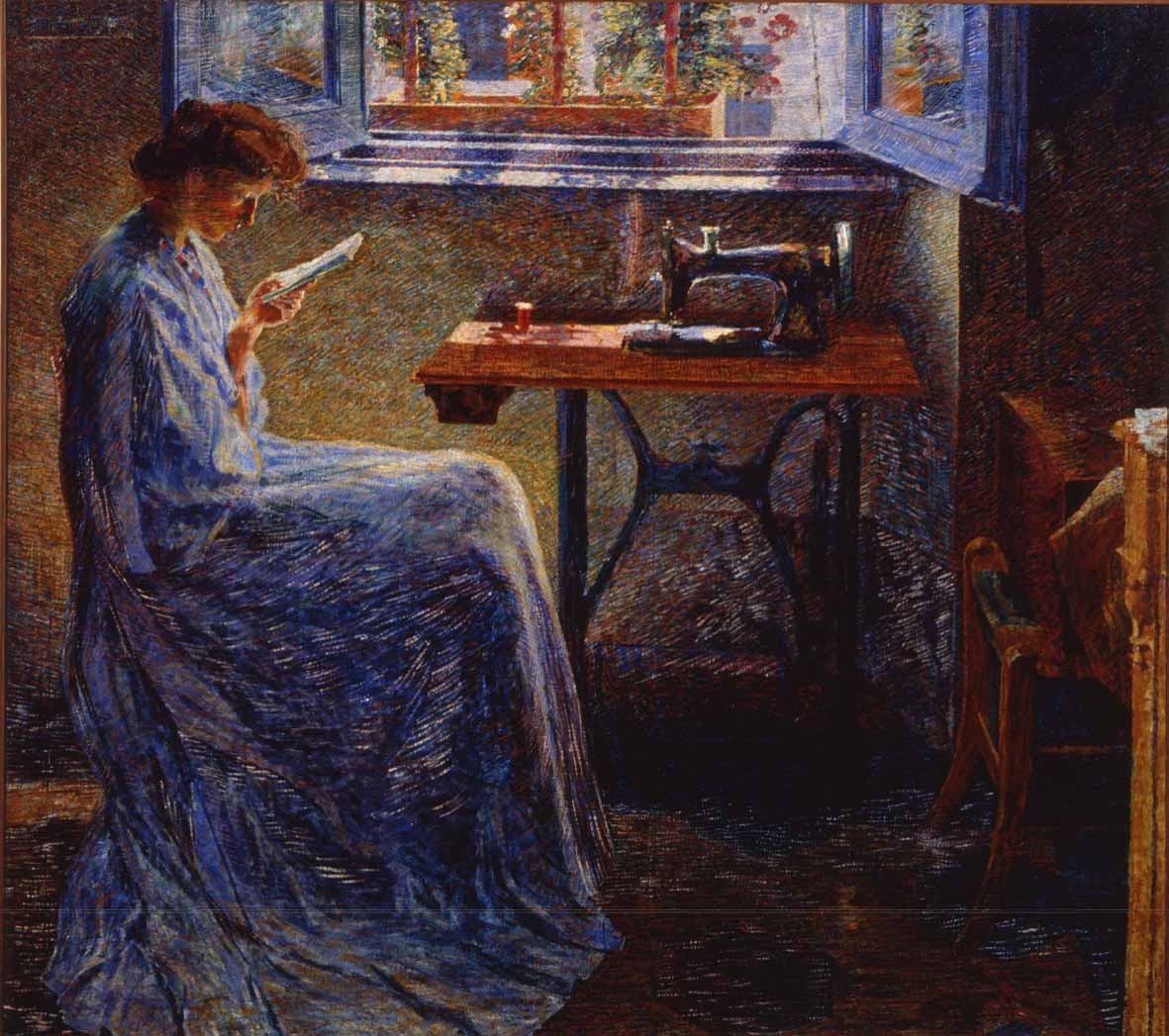

The evocation of that “ideal” to which Boccioni’s art aspires does not occur, as might be expected, only through landscape painting. There are, meanwhile, works with more distinctly Symbolist overtones, such as Veneriamo la madre or Beata solitudo, sola beatitudo, set against anAssumption by Gaetano Previati, and then there is the whole range of figures, from portraits up to the Romanzo della cucitrice. This strand is anticipated by a masterpiece by Giovanni Sottocorniola, Mariuccia, a highly refined portrait of a little girl against the light, executed in pastel, exhibited only once in 1985, which gives the public an account of the most up-to-date research of the Divisionists who explore light, torture it, break it down, and investigate it in search of the most vibrant and evocative effects. It is the time for the masterpieces of the last prefuturist Boccioni, heralded by two intense works on paper, Sister Working, a portrait of his sister Amalia intent on sewing, and My Mother, both characterized by an overcoming of the real oriented in two different directions, the first toward impression and the second toward an almost Renaissance idealism (Boccioni, speaking of his mother’s ink drawing, declared that he was inspired by Dürer and Raphael). Here, then, is the more experimental Boccioni: If Controluce, a work of 1909, despite not yet severed ties with Balla now shows full freedom, especially in the choice of compositional cut and in the reflection on light (it is a work in which the artist, Calvesi argued, “thus fully realizes the conversion into expressive datum of that luminous charge and that intense and dense sensibility materic sensibility”), the Portrait of Fiammetta Sarfatti, a work from 1911 (and therefore slightly later than the time horizon taken into consideration by the exhibition), is pure chromatic and luministic effect, while The Romance of the Seamstress is one of the culminations of Boccioni’s prefuturist “idealism.” the protagonist, writes D’Agati, “is abstracted from the reality that surrounds her, she lives in a silent, almost dream-like spatiotemporal otherness,” with light becoming “the means of concretizing this momentary suspension,” with the extreme simplification of the composition, elements that would convince Boccioni himself that he had succeeded in coming close to Previati, that he had succeeded in his attempt to “pour the true into the form of the idea.” A few months later, Boccioni would paint Rissa in the gallery and especially La città che sale, paintings that conventionally stand at the beginning of his journey into Futurism.

It was not a linear path, Boccioni’s: his research is made up of constant second thoughts, backward glances, sudden advances, disappointments and repentances, spurts and enthusiasms. The Controluce still linked to Balla, for example, is later than the Stitcher’s Novel. Certain illustrations of jockeys similar to those that most bored the rookie Boccioni coincide with the months of his most modern and up-to-date Milanese research. Even later, as a Futurist painter, he would tend to revise certain judgments that had matured in the years leading up to his breakthrough. Thus, from the exhibition at the Magnani Rocca Foundation emerges the varied and heterogeneous path of an extremely complex personality who would not fail to experiment through any medium: in this sense, the focus dedicated to engraving, presented in the Paduan-Venetian section (Boccioni practiced engraving in Venice together with ALessandro Zezzos), with also some unpublished works, assumes a not insignificant relevance in the itinerary of the visit. A decisive path for the Futurist Boccioni: the effective elaboration of a painting of states of mind, which brings Boccioni into the groove of the most up-to-date art of his time, is the prelude to the birth of the Futurist Boccioni and is the point of arrival of an exhibition that, on the strength of an established working group (composed in part of the same professionals who, for example, last year worked on the fine exhibition on the early Dudreville at the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca), is among the most interesting initiatives of the season.

The catalog, finally, stands as an important tool that updates the now already numerous studies on the prefuturist Boccioni by tracing an in-depth path also here divided by geographical stages (each city corresponds to a different essay by the curators), referring to the historical cornerstones of Boccioni’s bibliography and giving an account of the most recent novelties and the latest findings. Complementing this is an essay by Stefano Roffi, director of the Magnani Rocca, which delves into the links between Boccioni and music, starting with one of the most precious works in the Parma foundation’s collection, namely Albrecht Dürer’s copy of Melancolia I, to be considered an integral part of the exhibition on Boccioni. “Dürer,” wrote the artist, who had a kind of adoration for him, “is great is a titan is as terrible as the genius of his creation can be.” Even while observing Dürer’s works, letting himself be carried away by the calm and strength of his compositions, Boccioni would have come to imagine his art “as a symphony of colors, lines and vibrations,” Roffi writes. And he would have succeeded.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.