White Carrara, another missed opportunity to talk about marble: review below expectations

Examined by scratching the surface a little, the seventh edition of White Carrara, the festival that has enlivened the start of summers in the historic center of the city of the marbles since 2017, looks a lot like a Monicelli film. It resembles the plot of The Usual Unknowns: also in Carrara, as in the movie, the protagonists attempted the breakthrough coup, enlisting the services of an outside professional, but ended up with a result well below expectations. The idea of the new municipal administration of Carrara, which took office in July 2022, was to radically transform White Carrara, an event that, after a series of editions organized in the substantial absence of’a curatorial cut, set up with what was passing the convent, had now become little more than a village festival, totally irrelevant outside the city limits, unfulfilling for the local public and incapable of attracting even the most bewildered and clueless tourist. It was therefore decided to shelve the White Carrara organized by scraping together what the willing artisans of Carrara made available to the need, and to set up an event with a new face: an exhibition that will last until October 1, artists finally fished out of the province as well, and artistic direction entrusted, as is appropriate, to a professional curator. The Dante Cruciani of the situation is the Milanese Claudio Composti, owner of mc2gallery and photography specialist, and the plan to win public and critical acclaim has envisioned an event divided into two parts: sculptures in the square and a photography exhibition at Palazzo Binelli, with free admission.

Certainly, the White Carrara of 2023 is an extremely superior exhibition compared to past editions (not that it took much: it was enough to realize that even outside the municipality there are those who work marble), but having freed the event from the amateurism of past years has not prevented it from the risk of finding on its hands, as in Monicelli’s film, a meager plate of pasta with chickpeas, a derisory booty compared to the predictions, which will be also difficult to measure in quantitative terms, since, at least during the writer’s visit to Palazzo Binelli, no one bothered to record visitor attendance. Of course, the idea of transforming White Carrara into an exhibition with a marked curatorial imprint, offering the public a thematic lunge on contemporary marble sculpture, was very good and could only be welcomed. The problem lies mainly in the execution: Still Liv(f)e. The Forms of Sculpture (this is the title of the 2023 edition) rests in fact on very fragile foundations, and has the appearance of a superficially organized exhibition, without a precise basic idea, with a handful of very different artists, so much so that the exhibition is not a mere exhibition.very different artists, so much so that in order to hold together such different expressive languages and so discontinuous even in the quality and solidity of the thought that supports the works, Composti made use of the most obvious justification: “to give visual feedback to the idea of the city as a constantly evolving creative forge,” playing “on the theme of the transformation of the unworked block to the various forms of contemporary sculpture” (so in the presentation penned by the curator). Which translated from the curators ’ language means, “let’s see how contemporary sculptors work stone.”

Three questions the exhibition asks: “How much has the concept of sculpture changed with the advent of technology? How much have classical canons been disrupted by the use of new materials, beyond marble, intervening in plastic art with video, photographic or robotic media? Where does the definition of sculpture end and the definition of installation begin?” In short, the topic is really too broad to have the pretension of solving it with the works of just eight sculptors. One could turn a blind eye if one were on a smaller scale, or if the curator made, as is appropriate on such occasions, a profession of non-exhaustiveness, merely pointing out clearly and conspicuously that the proposal merely seeks to provide some coordinates for the public, and does not have theambition to give answers that the selection in question is unable to provide, because the questions are challenging and because the proposal is monstrously deficient, in quantity and quality, with respect to the stated topic.

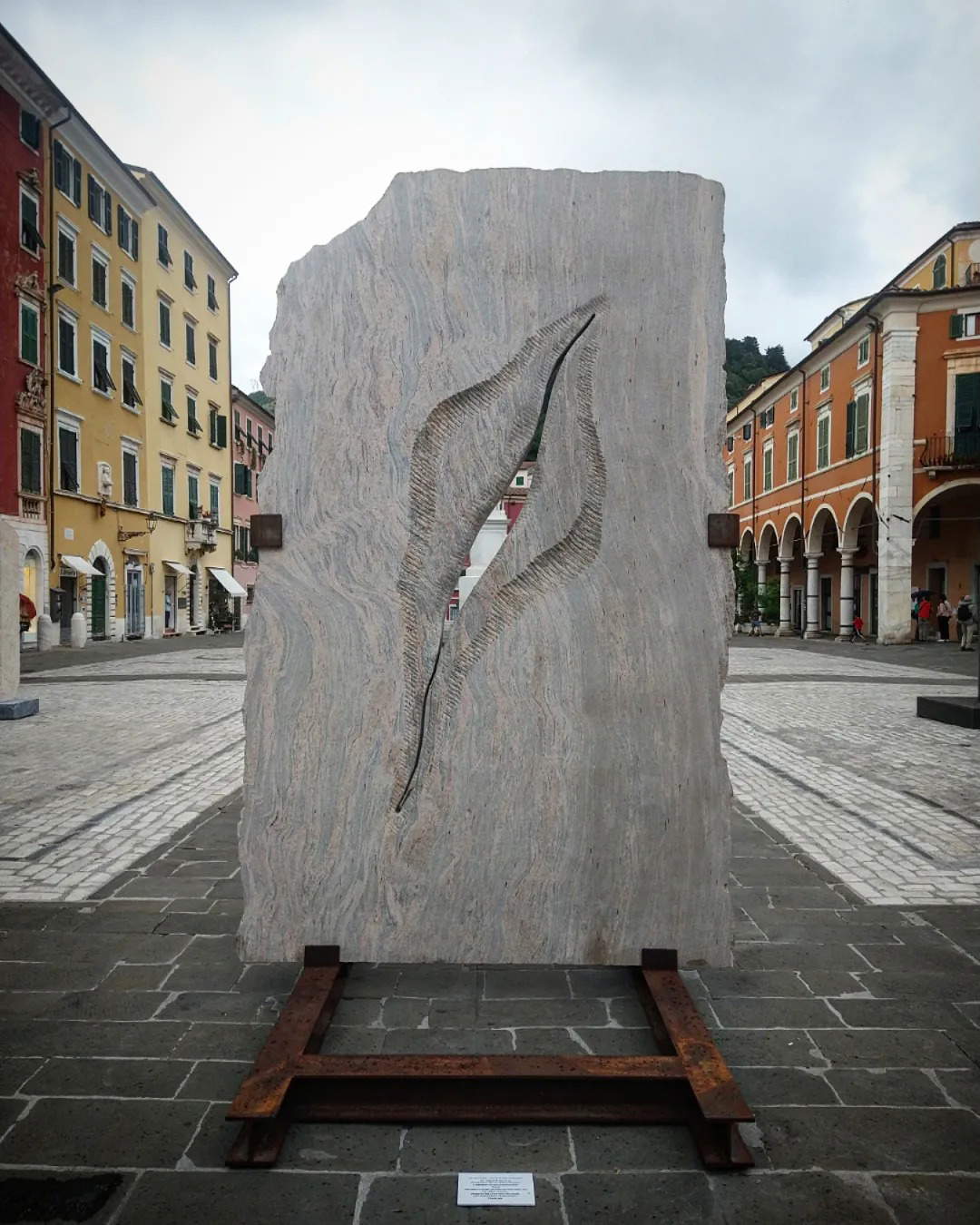

Then there is the issue of the local material: White Carrara, despite its tons of indefensible flaws, has in most past editions at least worked hard to give marble the appropriate prominence. This year, in Alberica Square, the city’s main square that has always hosted the heart of the event since the first edition, it welcomes the public with a work in Indian granite, one in Roman travertine and one in black marquiña, or Spanish marble. Not exactly the best calling card to introduce contemporary Carrara marble sculpture to the public. Yes, there is a sculpture by Giò Pomodoro in statuary, under glass: in fact, it can be seen behind a window of the InfoPoint in Alberica Square, in a defiladed position, difficult to spot at a glance. It is natural, then, that the public should focus on the three main works, which are so different and disjointed, and above all forced alone to shoulder about a third of the exhibition, that any reasoning about the tightness of the material on display with respect to the stated topics is impossible. And then, what material: the audience is welcomed by the granite pussy, moreover also drawn in an ungainly and cheesy manner, of Morgana Orsetta Ghini, an artist who for practically her entire career has done nothing but produce female genitalia in all materials, always with the usual clichés of the female organ as “source of life,” “origin of the world,” and assorted rhetorical repertoire. All this while Roberto Bernacchi’s bolted Vulva , a marble work that predates Morgana Orsetta Ghini’s late vagina by almost forty years, and above all a decidedly more disturbing work, lies languishing among dirt, sediment and wild grasses in the garden of the municipal RSA, forgotten by all, first and foremost by those who must have thought that bringing Ghini’s work to Carrara’s piazza should be big news. Next, there is then the stele by Sergi Barnils, who does nothing more than carve on travertine the marks he usually paints on canvas, and Michelangelo Galliani’s arm, a work that is anything but monumental, and totally unsuitable for an installation in the square.

Then there is Giò Pomodoro, who is present not only with Crowd Under Glass in Alberica Square, but also with a large Crowd in front of the Academy headquarters: it is not clear, however, why the sculptor from the Marche was chosen to serve as the “historical” introduction, so to speak, to the exhibition, since Composti in his very terse text does not give any reasons, increasing in the visitor the feeling of having happened upon a patched-up exhibition. The batch of sculptors continues with Quayola, present with a work that, with supreme scorn for the ridiculous, is said to be “inspired by Michelangelo’s technique of the ’unfinished’” (this is a bit like saying that Francesco Sole s’inspired by Joyce’s stream of consciousness ), and which is nothing more than the usual re-proposition of an ancient masterpiece, in this case Giambologna’sHercules and Nessus , revisited in this case in digital sauce: if you will, a kind of Fabio Viale who, instead of tattooing ancient works, deconstructs them by making use of algorithms. Reading the texts on the White Carrara totems (without being distracted by the delightful ballasts used to keep them from flying away), one will learn that according to Composti, Mattia Bosco, who is exhibiting his Sezione aurea in front of the side of the Duomo, was also inspired by “Michelangelo and the unfinished” (evidently one disciple in an exhibition ofeight artists was not enough) to present the public with rocks quarried directly from the mountain on which the artist intervenes with some gold leaf applications, which are, one reads on the totem pole, “Bosco’s parsimonious responses to the chromatic nature of stone” (whatever that means), and aim to reveal “what is hidden in the stone” even reconnecting with the philosophical concept of Deus sive Natura: Definitely pretentious challenge for these luxurious pieces of furniture (there is, moreover, a well-known design company, Alimonti, that has put out a similar object: it is called “Masterstroke” and differs from Bosco’s sculptures only in the fact that the parts are reversed, i.e., the outer shell takes on geometric shapes and the gold leaf interior is left raw to make the fracture stand out). It concludes with Armenia’s Mikayel Ohanjanyan, the 2015 Golden Lion winner who brings to Carrara two large blocks(Legami) of Indian quartzite, and with Stefano Canto and his concrete works grafted onto tree trunks: purely derivative poverist works that will immediately call to mind the language of a Penone or an Uncini.

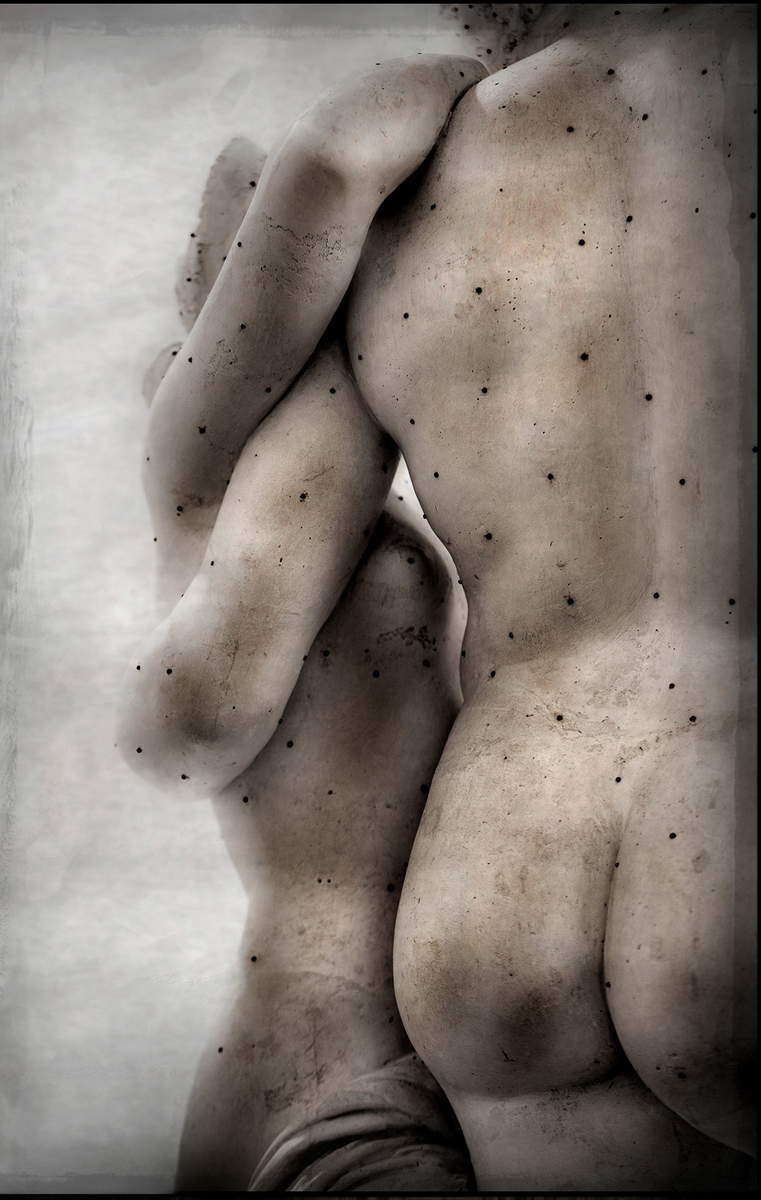

Stefano Canto’s works are on the first floor of Palazzo Binelli, where the photographic section of Still Liv(f)e is housed. And if of sculpture practically nothing is saved, it goes a little better with photography, with an exhibition that aims, Composti writes again, to propose “six ways of seeing and telling the versatility of an ancient and fascinating material like marble, always alive and multiform, through the interpretation of their ’plastic visions.’” The presentation, fortunately, is less bombastic than that of the sculpture section: here, at least, there is no attempt to give answers to questions that are too extensive for White Carrara’s paltry selection, and the audience is informed from the outset that the aim of the exhibition is to present the ways in which the six selected artists observe and photograph marble. The start, however, is bad: the Sculptures series by French artist Dune Varela is a kind of cheap re-edition of Elisa Sighicelli’s Storie di pietrofori e rasomanti (in short, we might as well have brought the Turin-based artist). The next room is better, with some shots from Bruno Cattani’s Eros series, which focuses on the asses, tits and nipples of classical statues: a work, started in 2000, that fits into the groove of photography of ancient statuary, cooked with all possible seasonings, by the various Amendola, Jodice, Spina, Visciano. Cattani is a kind of Herbert List who, instead of taking pictures of living bodies, prefers marble statues: the “sensuality of marble” is a rhetorical device that is now out of date, but Cattani was one of the first to work on this theme and, above all, his photography appears sincere and heartfelt.

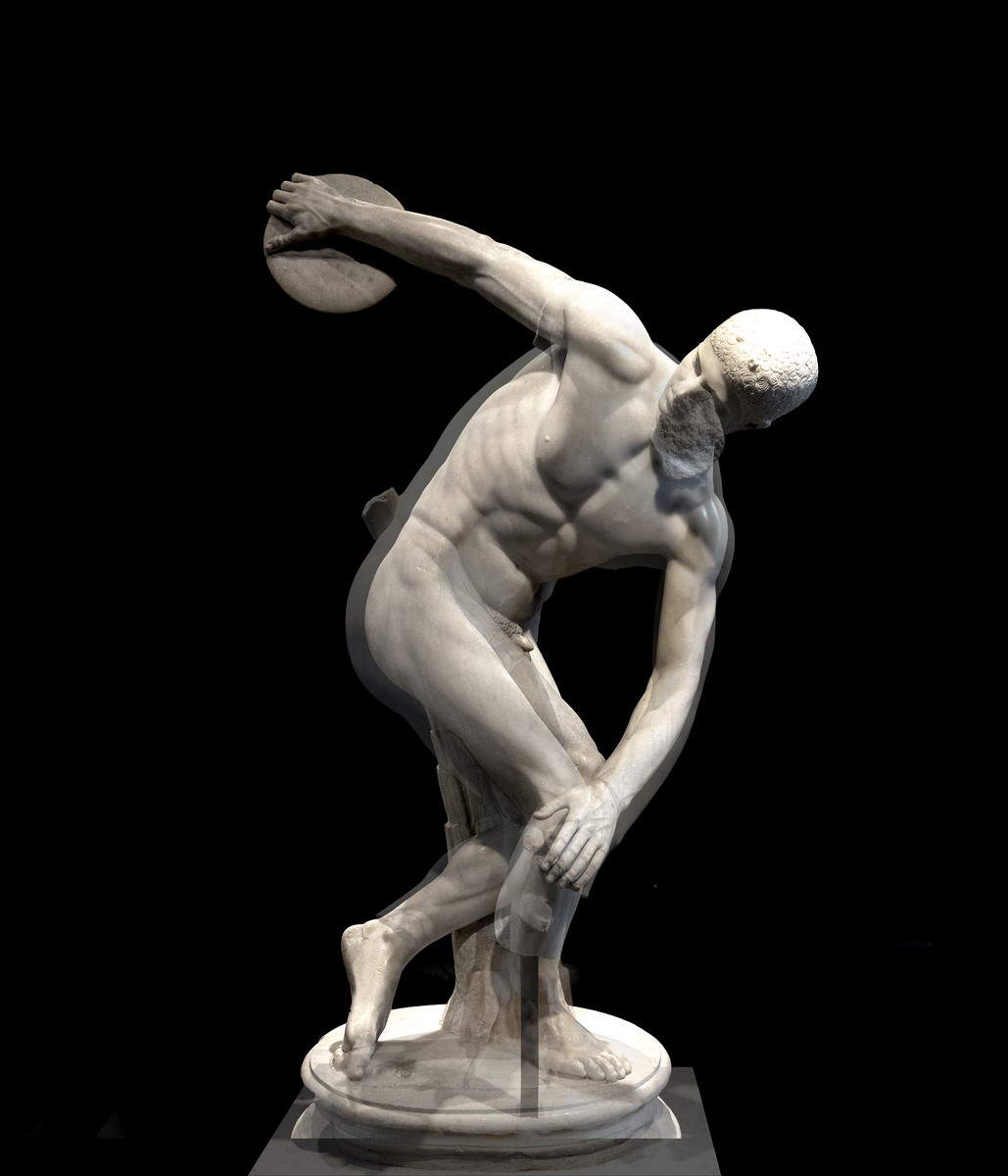

In the next room, on the other hand, we witness a trivialization of Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility by Carolina Sandretto, who, we read in the text, “in order to regain the aura to works of art [...] photographed some of the most famous Greek and Roman statues,” and superimposed variants of the same subject “thus creating a visible effect that reproduces the idea of aura, giving a body to something intangible, through a doubling.” beyond the incomprehensible anachronism behind this work (for what reason is there to “find the aura to works of art?”), the disconcerting conventionality of the iconographic device (the aura taking the form of a halo around the work, albeit achieved through overlapping) and the paradox of wanting to “rediscover the aura” through a mechanical reproduction (which could perhaps work if it were presented as a kind of situationist détournement , but in the illustrative text there is no irony, on the contrary: it is said that the splitting almost allows us to “see the invisible”). Appearing fresher is the work of young Giacomo Infantino, who has traversed the landscapes of the Apuan Alps by illuminating them at night with colored lights to transform the views into dreamlike images, while Englishman Simon Roberts, with his series Beneath the Pilgrim Moon, brings to Carrara shots that capture the sculptures of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum covered by transparent plastic sheeting during museum closures for anti-Covid restrictions: an interesting work that received positive acclaim when it was presented. Conclusion on the ground floor with the works of Andrea Botto, who, taken perhaps by an access of nominative determinism, has chosen to devote a substantial part of his research to images of explosions, and to Palazzo Binelli he brings a video and a photograph (the demolition of the social housing in the neighborhood of Caina, in the center of Carrara) that should show us “the landscape at the moment of its transformation, dissolution, collapse.” And in Carrara, indeed, the dissolution and collapse of the landscape constitute a tremendous daily reality for its inhabitants: who knows if Composti’s intent was to activate such kind of reflections as well.

Even with the new course, in short, White Carrara remains an initiative that essentially lacks a defined character. One struggles to understand the meaning of Composti’s work in Carrara: an attempt to relaunch an event that is now meaningless, carried on, however, with logics not too dissimilar from those that had sustained the old editions? A kind of micro-Biennale of Sculpture to recall the glories of Carrara of yesteryear? A transitional exhibition while waiting for clearer ideas on how to orient White Carrara in the future? Whatever the intent, the fact is that audiences arriving in Carrara will find a weak, patched-together exhibition, with a selection wholly insufficient to meet the overly ambitious goal stated in the curator’s text, and with a photographic survey that, beyond a few good ideas, has little to offer visitors.

If the intention was to set a new course, the result resembles more a disbandment that makes evident the irretrievability of an event that began badly, continued worse, and that by 2024 it would perhaps be wiser to retire for good. Let us therefore intone the Requiem for White Carrara. Let us have the courage to say goodbye, without regrets, to an exhibition that has never been able to make an impact, that has never left traces, that has always wallowed in mediocrity, that has always been exaggeratedly modest for a city that until not so long ago was home to much larger exhibitions. Let’s bury the White Carrara and think about the past: in the last twelve years, Carrara has tried all possible formulas to put marble at the center of its summer cultural proposal. The experience of the International Sculpture Biennial, which began in 1957, was interrupted in 2010 with a biennial, Post Monument curated by Fabio Cavallucci, of the highest level, but with little public response. Having archived the Biennials, it moved on to design and Marble Weeks curated by the late Paolo Armenise and Silvia Nerbi: quality and success with the public. Then came the White Carrara built with the contribution of local workshops, without an authoritative artistic direction: poor quality and little public. Finally, the current White, a sort of bonsai of past Biennales, an idea that might be good on paper, but which materialized into a ramshackle, uneven event with very few high points. Questionable quality, on the audience will be drawn in October. Here it is: the various experiments point to perhaps the most suitable format, at this moment in history, for Carrara. Let there therefore be an attempt to return to design. Let us dust off the format of the old Marble Weeks that had the merit of characterizing the city and projecting it into a new, seductive, useful dimension. Let Carrara be tried to make a comeback on more prestigious stages.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.