When puppets are art and avant-garde. Their history on display in Reggio Emilia

In an age dominated by social media, new technologies and the emerging artificial intelligence that is already creating deep debates both on its role and on the necessity or otherwise of human presence in given areas, who knows if the new generations still feel a fascination for puppets and marionettes. I remember that as a child, very often on summer evenings, accompanied by my parents, I would find myself attending fantastic puppet and marionette shows that, moved by the skilful hands of puppeteers or marionette players, would set up with a shack and a castelet stories in front of which I would be magically enchanted and enraptured. Today we see less and less of these shows, they are almost disappearing, and I think it is bad for the society of the present, because you take away from the new generations that sense of magic that animates that world and you make them more and more deprived of that good imagination and creativity that makes even the most insignificant plastic bottle or an ordinary paper bag turn into a character of a fantastic story. It is a sensibility that moved the Palazzo Magnani Foundation to create the exhibition Puppets and the Avant-Garde. Picasso, Depero, Klee, Sarzi, running through March 17, 2024, curated by James M. Bradburne, at Palazzo Magnani in Reggio Emilia. However, the idea that, given the theme, this is an exhibition aimed only at children should not be fooled: while playful, colorful, and enjoyable to visit, the exhibition brings into play such themes as the great avant-gardes of the early 20th century, its artists, and theater. Young visitors will surely have fun discovering the strangest creations born from the imagination of the artists and will experience this exhibition as a playful discovery; adults will probably walk through this exhibition with a sense of nostalgia that will take them back to their childhood, but above all they will have the opportunity to learn about the history of puppets and marionettes through the twentieth century.

It is therefore an exhibition capable of fascinating everyone, young and old. Who said that puppets and marionettes are only things for children? Suffice it to think, and this is one of the main objectives of this exhibition, that the artists of the early twentieth century, instead of considering “puppets” as mere childish games, saw in them a great potential, starting from youthful curiosity, both to imagine through the same representations a better world and as instruments of social change in the revolutions that marked the first half of the century. The reappropriation of puppets and marionettes by the European avant-garde in the early twentieth century is therefore cast in the context of the historical period, in the sense that, with the exception of indigenous traditions, artists often made these creations precisely to present the society in which they lived, with the intention of breaking that boundary between art and life; to criticize political and social conditions and perhaps imagine a better world, thus spreading these ideas through new modes of visual expression, as a kind of creative game that nevertheless carried deeper and more topical meanings.

Walking through the rooms of the exhibition and its sections, marked distinctly by the various experiments that followed one another during the first decades of the twentieth century and by its protagonists, one actually makes, as stated by the president of the Palazzo Magnani Foundation Maurizio Corradini, “a journey through time and space through the experiments of visionary artists” and through “the main European traditions of twentieth-century figure theater.” In fact, each section explores a specific time and place in the early decades of the twentieth century, as well as how theater is transformed from a performance dominated by actors to a total art form created by avant-garde directors.

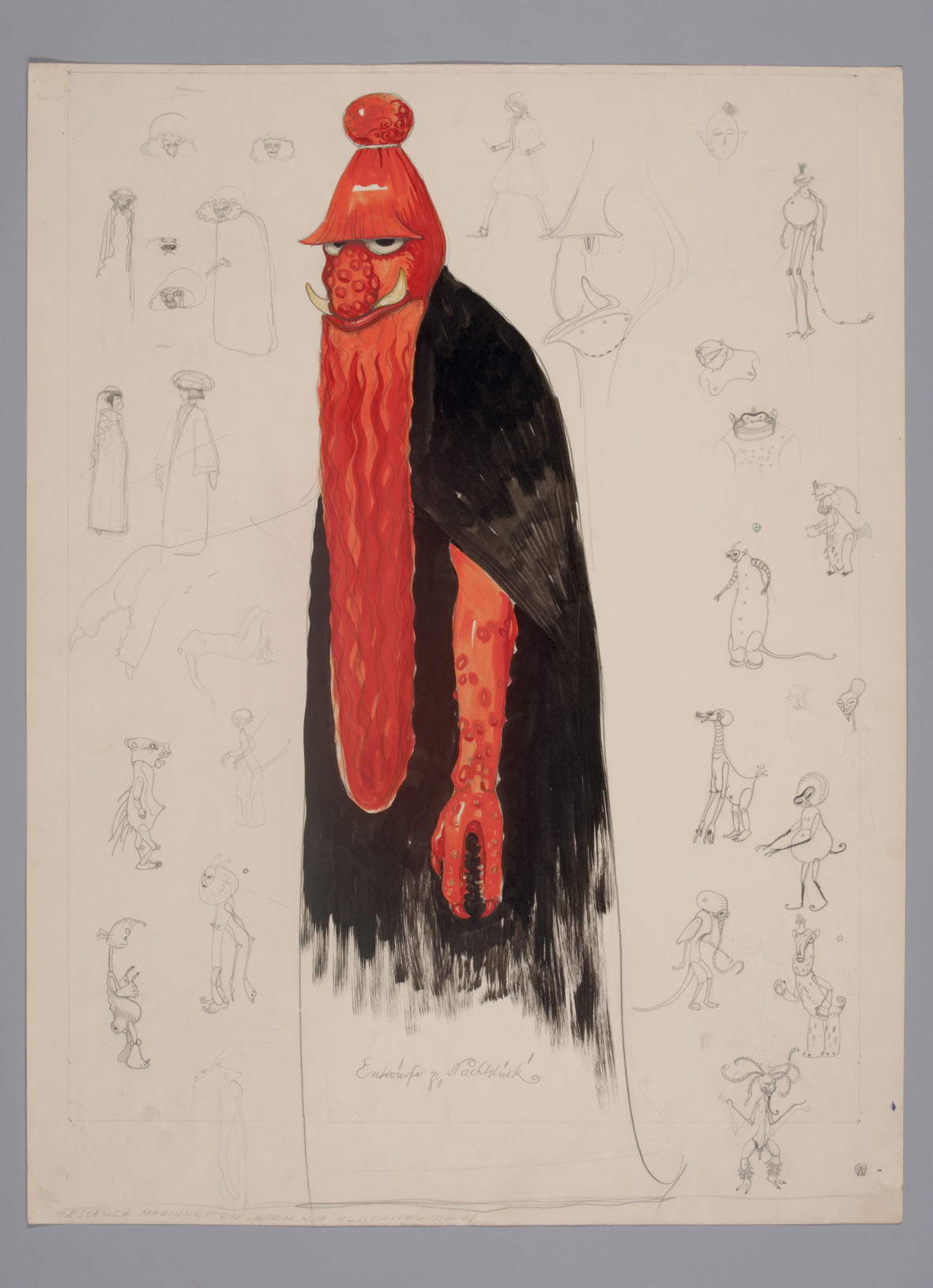

It starts with four life-size costumes (including Le prestidigitateur chinois and the Manager américain) designed by Pablo Picasso for Parade, a plotless choreographed ballet brought to the stage by Sergei Djagilev’s Ballets russes in Paris in 1917, which constituted a kind of parade of fairground performers giving each an essay of their number. We move on to the 1920s futurism of Fortunato Depero with his Balli plastici, which put on stage moving wooden forms accompanied by music depicting animals (among the most famous, the black cat, rooster, mice), or characters such as the white puppet and the red savage, made with the help of his friend and patron Gilbert Clavel, to celebrate the pure gesture of movement, in full futurist view, with the elimination of even the actor. Depero’s marionettes were first presented at the Teatro Odescalchi in Rome in April 1918. The original ones were destroyed after a few years, but the design drawings ended up in Rovereto when Depero himself opened his Casa d’Arte Futurista in the Trentino city in 1919. They were then rebuilt in 1981 following the artist’s own designs and are now kept at the Mart in Rovereto, where the ones on display in the exhibition come from. Then we meet Enrico Prampolini ’s ten Futurist puppets made in 1922, which represent both caricatures of characters who at that time held important political and cultural roles, such as Gabriele d’Annunzio, Giovanni Giolitti, King Vittorio Emanuele III, Benito Mussolini, and Dina Galli (the only female puppet) and concepts, such as the world or fascism.

One section is devoted instead to the classic Javanese leather-carved puppets , known as Wayang, of the so-called Shadow Theater, which were used at village festivals, community rituals or rites of passage and thus occupied an important role in divinatory magic and political oratory. Still highly valued today, they appeared in Europe in the late 19th century thanks to merchants and travelers in the wake of a taste for the Orient; since 2003 they have been protected by UNESCO as a form of Indonesian intangible cultural heritage and a masterpiece of humanity’s oral and intangible tradition. He was inspired by the principle of Wayang movement, moved by sticks from below (a main rod supported the figure, while other rods allowed the movement of other parts, e.g., the limbs), by Bohemian Richard Teschner, considered one of the greatest innovators of twentieth-century puppet theater, as he overturned the traditional process of puppet animation. His puppet theater took shape around the Wiener Werkstätte: the wood-carved figures were dressed in fabrics from the Wiener Werkstätte or painted with ornamental motifs like those of Egerland folk art, thus creating a symbiosis between cultural traditions of the East and the European pictorial world. Teschner’s is a theater without language, which is reduced to gestures, and which he captures himself since “the puppet is a lifeless structure as long as it hangs in the puppeteer’s box, but as soon as he takes it in his hands and leads it on wires or by means of rods on small, refined stages, it experiences a strange animation and an almost uncanny life of its own.” Some of his puppets can be seen in the exhibition, including the beautiful Nawang Wulan and the strange, almost alien-looking creatures Zipzip and the Yellow.

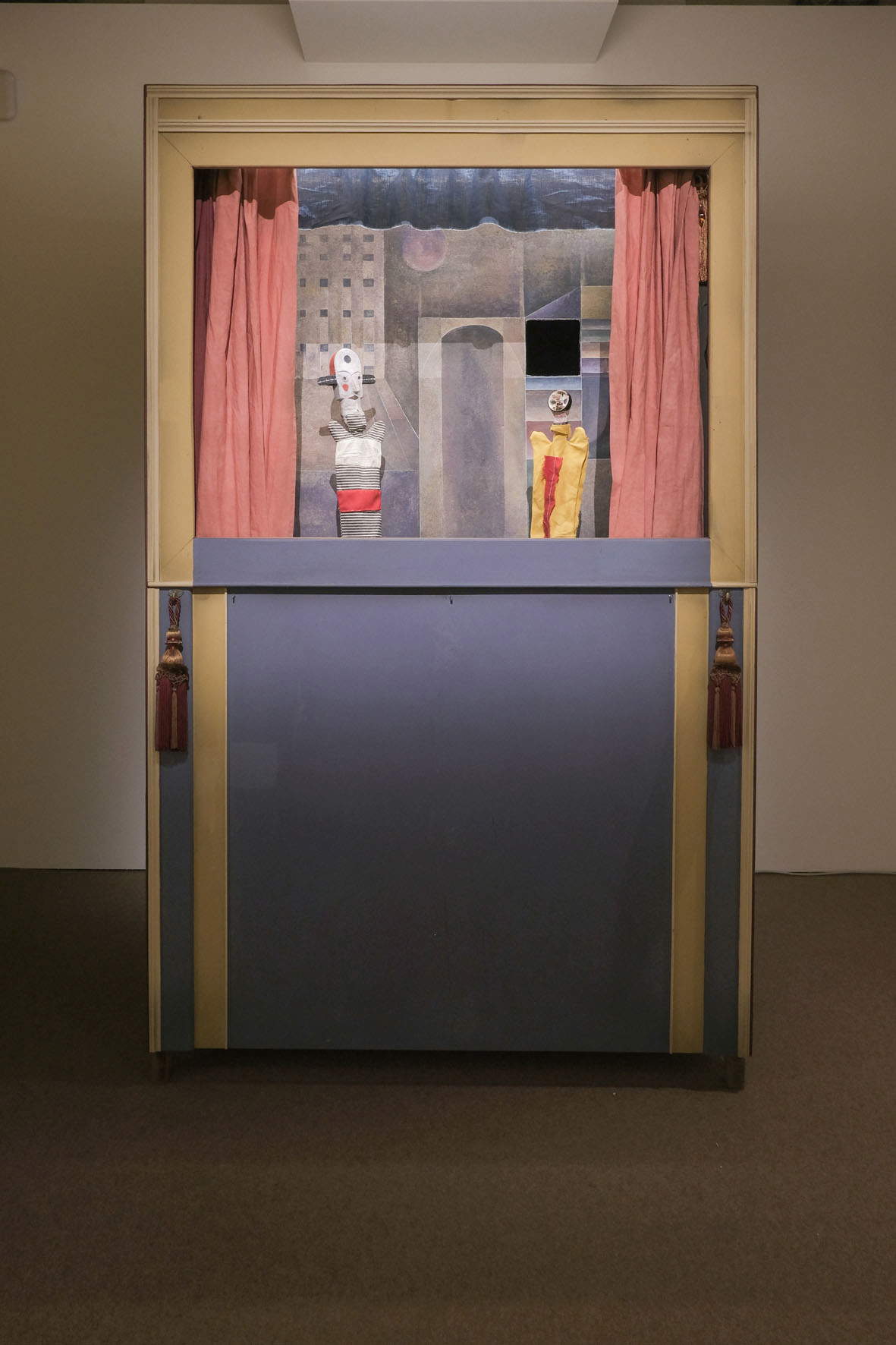

And then there are the puppets of Swiss Sophie Taeuber, wife of the Franco-German artist Jean Arp: in 1918 she was asked to design the puppets and sets for the text of Carlo Gozzi ’s commedia dell’arte Re Cervo adapted by Werner Wolff and René Morax, which the latter turned into a parody of Freud’s psychoanalysis. There are then the “sounding” puppets of King Deramo, the Guards, the Stag, Dr. Komplex, and the Parrot, which are also presented in motion in a video production visible in the same section of the exhibition.

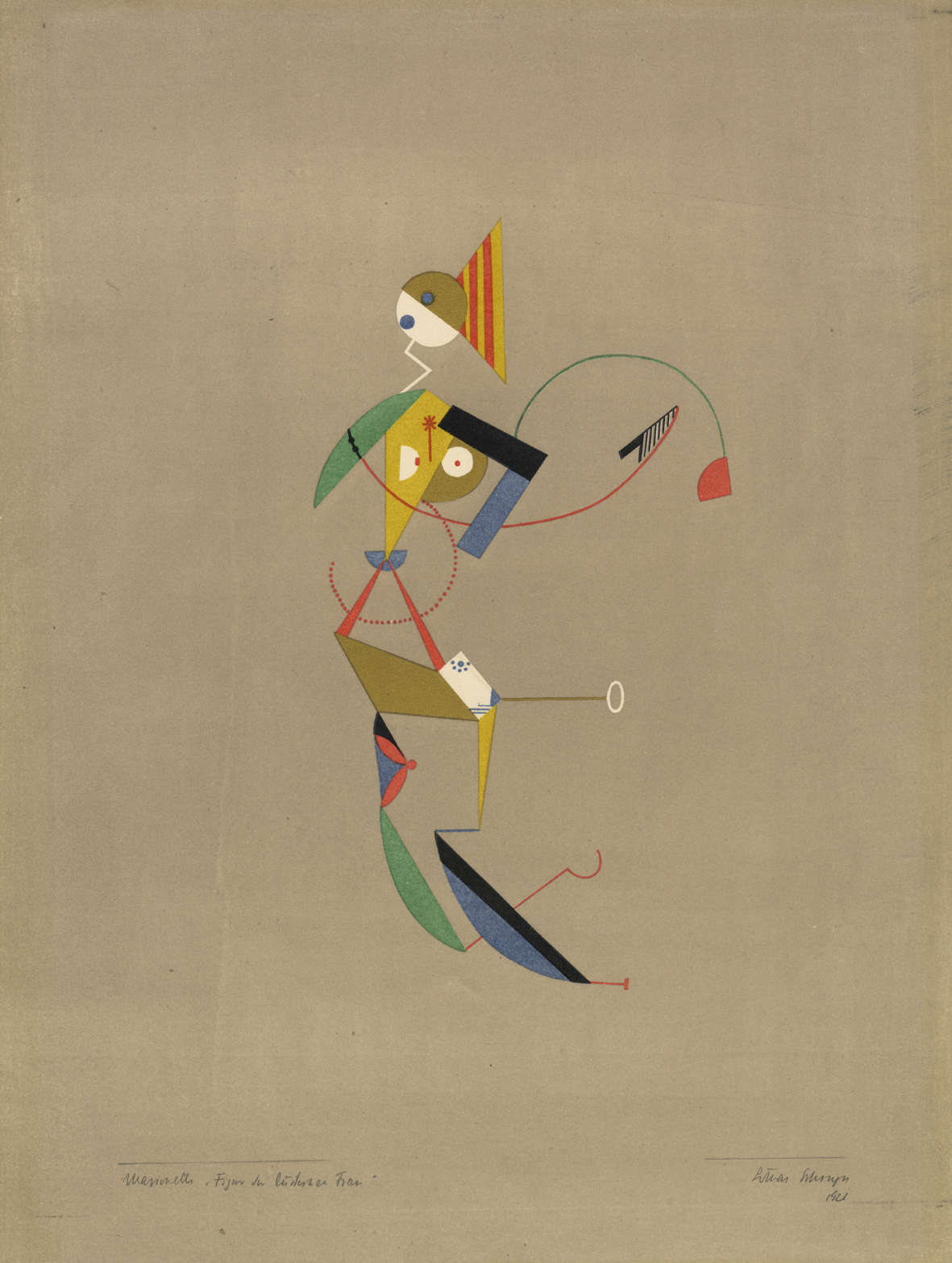

We then move on to the Weimar Bauhaus of the 1920s, whose protagonists in the use of figurine-marionettes (influenced by the rediscovery of Heinrich von Kleist’s work, The Puppet Theater of 1810) are Lothar Schreyer, the first director of the Bauhaus theater workshop (1921 to 1923) and his successor, Oscar Schlemmer (1923 to 1929). Geometric figures such as the Lustful Woman, theLustful Man and theAngel of Birth for Schreyer’s Geburt puppet show, plans for which are preserved, as we can see in the exhibition, and Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet first performed as the culminating event of the Bauhaus Week celebrations in August 1923, with full-body sculptural costumes that transformed the dancers into stylized puppets. It was actually an anti-ballet, a plotless symphonic dance divided into three sections, from allegro to serio.

Paul Klee, a teacher at the Bauhaus, also made a series of puppets and a puppet theater for his son Felix. Klee took his then eight-year-old son to the puppet theater at the Auer Dult flea market in Munich: here the latter was so fascinated by Kasperl ’s mischievous and pugnacious character that his father as a birthday present created for him a series of handmade puppets of the characters from the show they had seen together, and even for family, friends and guests Felix staged real domestic plays.

We continue with theRussian avant-garde: artists such as El Lissitzky and Nina Efimova found in puppets and marionettes the freedom that was often absent in more conventional media. Lissitzky designed his figures primarily to present the bright future of the international proletariat, conveying an idea of the new society and new art through abstract images. They are figures composed of various pieces that take on the appearance of moving machines rather than human bodies, and each character has the shape of the work he or she does, for example, theAnnouncer includes a megaphone that emits the sounds of railway stations, the roar of Niagara Falls, and the pounding of steel mills; the Globetrotter has a propeller-shaped body, symbolizing the plane on which he or she travels. The bodies of the Undertakers are abstract coffins with crosses on them. But it is theNew Man who fully embodies a political message, spreading the idea that the future man is communist, like his vision (the left eye is formed by the Soviet red star); Lissitzky himself claimed that “the communist system of social life is creating a new man: from a small and insignificant wheel of a machine, he has become its captain.”

Finally, sketches, posters and projections pay homage to one of the pioneers of experimental children’s theater: the painter and puppeteer Nina Efimova. In the fledgling Soviet state led by Lenin and his wife, puppets became an excellent tool to combat widespread illiteracy and to educate the new Soviet citizen, and with this in mind, artists such as Efimova used puppets as a propaganda medium to engage the masses starting right from childhood. The characters were thus stereotypical and easily identifiable and often embodied political and social types. Among her most famous creations is the Russian puppet Petruška (we see him in the exhibition sitting on a bench waiting for company).Nina took him everywhere, in the many performances she held around factories, schools, workers’ clubs, and on the streets of Moscow with her husband Ivan (with the Efimovs, the popularity of fairground puppets grew tremendously).

The exhibition concludes by celebrating Reggio Emilia puppeteer Otello Sarzi (Vigasio, 1922 - Reggio Emilia, 2001) with a dedicated section. First a young helper in the family’s traveling troupe, in the 1950s he began a collaboration with Gianni Rodari by making masks for the children who were the protagonists of the characters in the writer’s stories. From then on, Sarzi devoted himself exclusively to puppet theater, dramatizing Alfred Jarry, Samuel Beckett and Bertolt Brecht, and making large figures with innovative techniques and recycled materials such as foam rubber, water bottles, cans and string. He then founded T.S.B.M. - Teatro Stabile di Burattini e Marionette- in Rome in 1957. In 1969 he moved with some members of the company to Reggio Emilia, and in the same year, Sarzi and his T.S.B collaborators began work in Preschools with Gianni Rodari, Loris Malaguzzi and teachers, collaborating on the project of a new pedagogy for childhood. On display are many of his puppets, including Angoscia, a character who expressed himself with expressionist gestures and represented the anguish of contemporary man in industrial society. This final tribute is actually one of the main intentions of the exhibition, which aimed to make the most of Otello Sarzi’s legacy of experimental theater by bringing it into dialogue with the main European traditions of twentieth-century figure theater, as illustrated so far.

Beautiful and singular was the idea of accompanying the exhibition with performances by the Carlo Colla Puppet Company of Milan and the5T Association of Reggio Emilia, to make visitors experience a moment of figure theater performance. An exhibition, therefore, to be visited to rediscover that fascination now unfortunately almost lost for the world of puppets and marionettes and to learn about its history throughout the 20th century.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.