When Monet and colleagues invented Impressionism: what the major exhibition at the Musée d'Orsay looks like

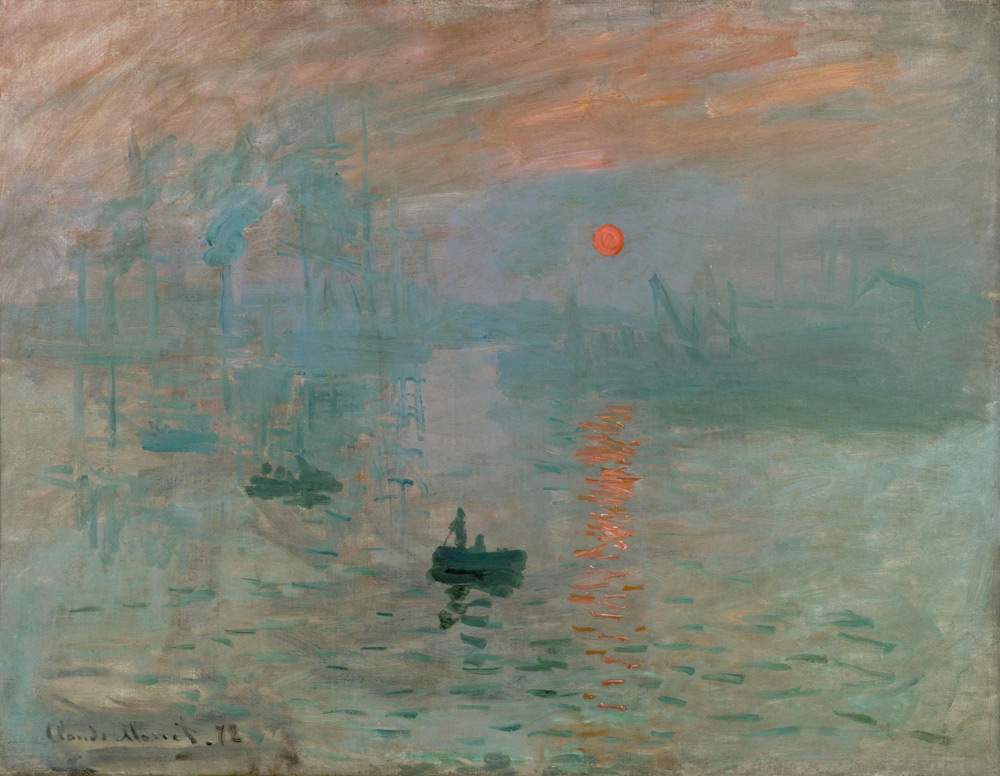

A unique exhibition, the kind you will never see again, or at any rate it will be a long time before you see one of the same caliber: the occasion is truly special, the 150th anniversary of the birth of French Impressionism, and if the desire was to celebrate this important “birthday” by doing things in a big way, the intent has truly succeeded. To visit this major exhibition, which has a total of about 130 works by the greatest exponents of the French movement, including some of the most celebrated masterpieces, such as Claude Monet ’s Impression: soleil levant and Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Bal du moulin de la Galette, one has to leave national borders and fly to Paris, to the Musée d’Orsay, where the exhibition Paris 1874. Inventer l’impressionisme, curated by Anne Robbins and Sylvie Patry and organized by the Musée d’Orsay and Orangerie and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (where the exhibition will be hosted from September 2024 to January 2025 under the curatorship of two other experts). It is a retrospective that alone is worth the trip (although going to Paris is always a pleasure) both for the quality and quantity of the works on display and for the well-constructed and by no means predictable itinerary, and an additional point in its favor is that the Musée d’Orsay, the museum of Impressionism par excellence, was chosen as the exhibition venue, where once you have seen the exhibition you can continue the full immersion among the Impressionists in the permanent collection. However, it might lead to a difficulty in fully enjoying the exhibition if it is too crowded, especially in the first few rooms, as happened to the writer, but by arming oneself with patience everything will go smoothly.

The ten sections of which the exhibition is composed, to which is added an introductory part that aims to illustrate through photographs the historical context in which the French capital was at that time, that is, a time in which it is still alive the memory of the destruction wrought by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and therevolutionary wave of the Paris Commune of 1871, but in which at the same time the city was beginning to rebuild and modernize, can actually be grouped into three macro-sections, which contribute to the uniqueness of this exhibition. A first part with the opening of the first Impressionist exhibition on April 15, 1874, and thus with the artists involved in this independent initiative; a second part devoted to the Salon, the official annual art exhibition that opened on May 1, 1874, and the works that were exhibited there; a third, so to speak, gray area part, with works that were at the Salon but could have been at the Impressionist exhibition, or works by artists who exhibited at both the Salon and the Impressionist exhibition, or common themes covered by both sides. In the main intentions of the exhibition, as stated in the preface of the catalog, is precisely this unprecedented comparison between a selection of works exhibited during the Impressionist exhibition of 1874 and some paintings and sculptures presented at the same time at the Salon: the goal is to restore the visual impact of the works exhibited by the Impressionists, but also to mitigate it by making it clear how between the first Impressionist exhibition and the Salon there were actually parallels and overlaps. Instead, the last two sections are devoted to Monet’s Impression, soleil levant, considered the work from which Impressionism began, and to the third Impressionist exhibition of 1877, the only one in which the artists from the first exhibition of 1874 exhibited all together again and which they themselves called an Impressionist exhibition.

The exhibition then kicks off, after the first introductory room, with a room where the curators wanted to take the visitor to number 35 Boulevard des Capucines, to the former atelier of photographer Félix Nadar: it was here on the second and third floors of the building that the first Impressionist exhibition opened on April 15, 1874. A photograph dating from around 1861 depicts what the facade of the building looked like when the atelier was active: a glass and metal structure on which the photographer had the large red Nadar sign installed. In 1871 the photographer left the building because it had become too expensive, but three years later it was Edgar Degas who realized that this was precisely the right space for the established Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc . (the fellowship that brought together the future Impressionists), of which he was also a member, to exhibit their works all together for the first time in an exhibition that would be independent of the official annual art show, the Salon. The space had seven or eight rooms, arranged on two levels, with an elevator. No photographs exist of that first exhibition, but it is possible to deduce at least roughly what the arrangement of the works looked like thanks to descriptions of the time; so the one ideally conjured up now at the Musée d’Orsay is based on these accounts, but nevertheless cannot be, so to speak, a perfect reproduction of the original exhibition 150 years ago. A 3-D film then tries to transport the viewer, in a zoom in zoom out, to the exhibition halls of that first exhibition, starting from the Boulevard des Capucines, passing by the facade of that building.

The exhibition of the Société Anonyme opened, as mentioned above, its doors on April 15, 1874, also in the evening hours to attract more visitors, with about two hundred works selected by the members of the society itself. According to the written accounts and the booklet, the only documents that have come down to us, in the first room of the exhibition, which seems to have been set up by Renoir, the public was able to admire the painting of Renoir himself and Degas, who presented in a new and more immediate language scenes of life in a Paris that was not only more modern but also linked to entertainment: works with ballerinas and spectators at the theater, with the boulevards teeming with people. Here, then, the third room of today’s exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, evoking that very first room, features several works with Degas’s dancers both on stage and in class, Renoir’s Loggia with two spectators at the theater, for which he had his brother pose, and a young woman from Montmartre; also by Renoir himself, the Dancer and the Parisian Girl, both looking at the viewer (the two paintings are the only large-format ones the painter exhibited in 1874), and the Boulevard des Capucines full of people depicted with quick touches by Claude Monet from the perspective of a balcony of the same building at number 35. Note how all the captions of these works read “First Impressionist Exhibition, 1874,” accompanied by the probable number this one had in the exhibition 150 years ago.

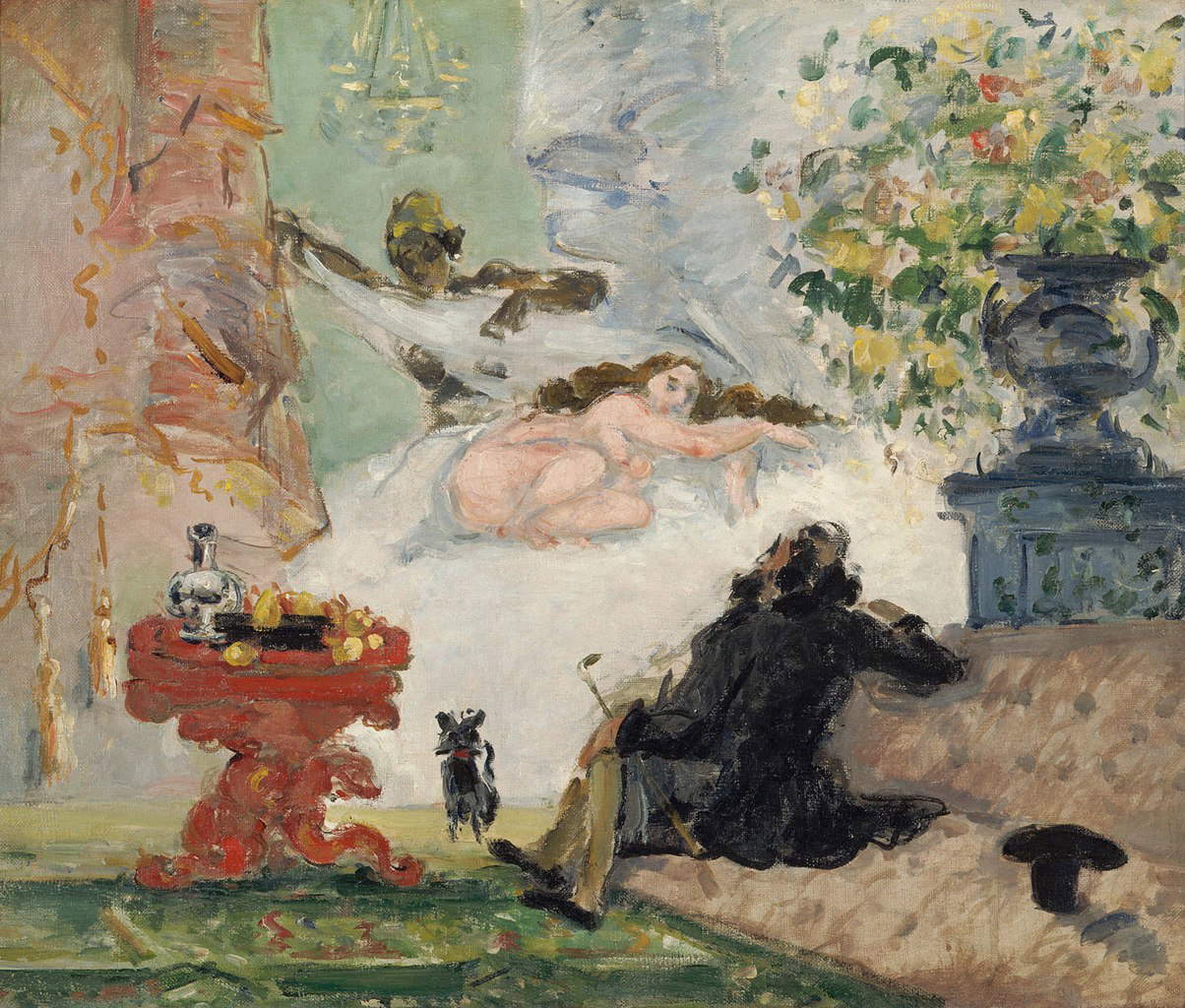

The next section, in a large room, is intended to make clear then how that exhibition was actually very eclectic, with works of a wide variety of subjects, techniques and styles: there are paintings, sculptures, prints, engravings, landscapes, interiors, hunting scenes. And even the participating artists, thirty-one in all, belonged to different generations and social circles, but they all shared a desire to exhibit in an independent, non-academic and juried context. In fact, to give an idea, we see exhibited here landscapes by Camille Pissarro and Édouard Béliard, a vase of flowers by Renoir, a synagogue interior by Édouard Brandon, an old fisherman by Adolphe Félix Cals, a portrait of Berthe Morisot’s sister, a bust depicting Ingres by Auguste Louis Marie Ottin, a selection of etchings by Félix Bracquemond, Théophile Gautier, Giuseppe De Nittis, and Ludovic Napoléon Lepic, and then watercolors with interiors, but above all A Modern Olympia by Paul Cézanne depicting the interior of a closed house with a nude prostitute, juxtaposed with the very tender maternal scene in Berthe Morisot’s The Cradle : indeed, we know that the two paintings were also close to the Impressionist exhibition and that it aroused negative comments because of the juxtaposition of the two scenes, one gentle and the other licentious.

As mentioned earlier, we then move on to the section devoted to the Salon, the great official exhibition with thousands of works selected by a jury under the patronage of the Directorate of Fine Arts that presented the artistic production of the moment every year; it opened fifteen days after the exhibition of the Anonymous Society, exactly on May 1, 1874, on the Champs-Élysées, in the Palace of Industry and Fine Arts. We know that huge paintings with historical, religious, mythological subjects, genre scenes, landscapes, and portraits were displayed there, and that almost two thousand were hung very close together. That is why the layout we find in the Salon section is built like a picture gallery, with paintings of various sizes juxtaposed with frames that almost touch each other: a poet by Henriette Browne, Jules Breton’s The Cliff , a monk carving a Christ in wood by Édouard Dantan, a dance scene in Tangier by Alfred Dehodencq, Éminence grise by Jean-Léon Gérôme, a Portrait of a Lady with Umbrella by Jean-Jacques Henner, Satyr with Bacchante by Henri Gervex, Adelaïde Salles-Wagner’s Reading Lesson, a Madonna and Child with St. John by Ferdinand Humbert, Eros Cupid by Jean Jules Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ, Jules-Élie Delaunay’s David Triumphant: themes, as you can see, really very different from each other, but with a very different, more set painting than that of the Anonymous Society. There are also two works by two artists, Mary Cassatt and Marie Bracquemond, who exhibited at the Salon that year but who exhibited with the Impressionists a few years later. Instead, the next small section presents scenes of war and battle, such as those depicted here by Édouard Detaille or Auguste Lançon, a theme that the 1874 Salon brings to the exhibition, because in any case the memory of war is still alive, but which on the contrary the Anonymous Society does not depict in favor of other, more mundane and happier aspects.

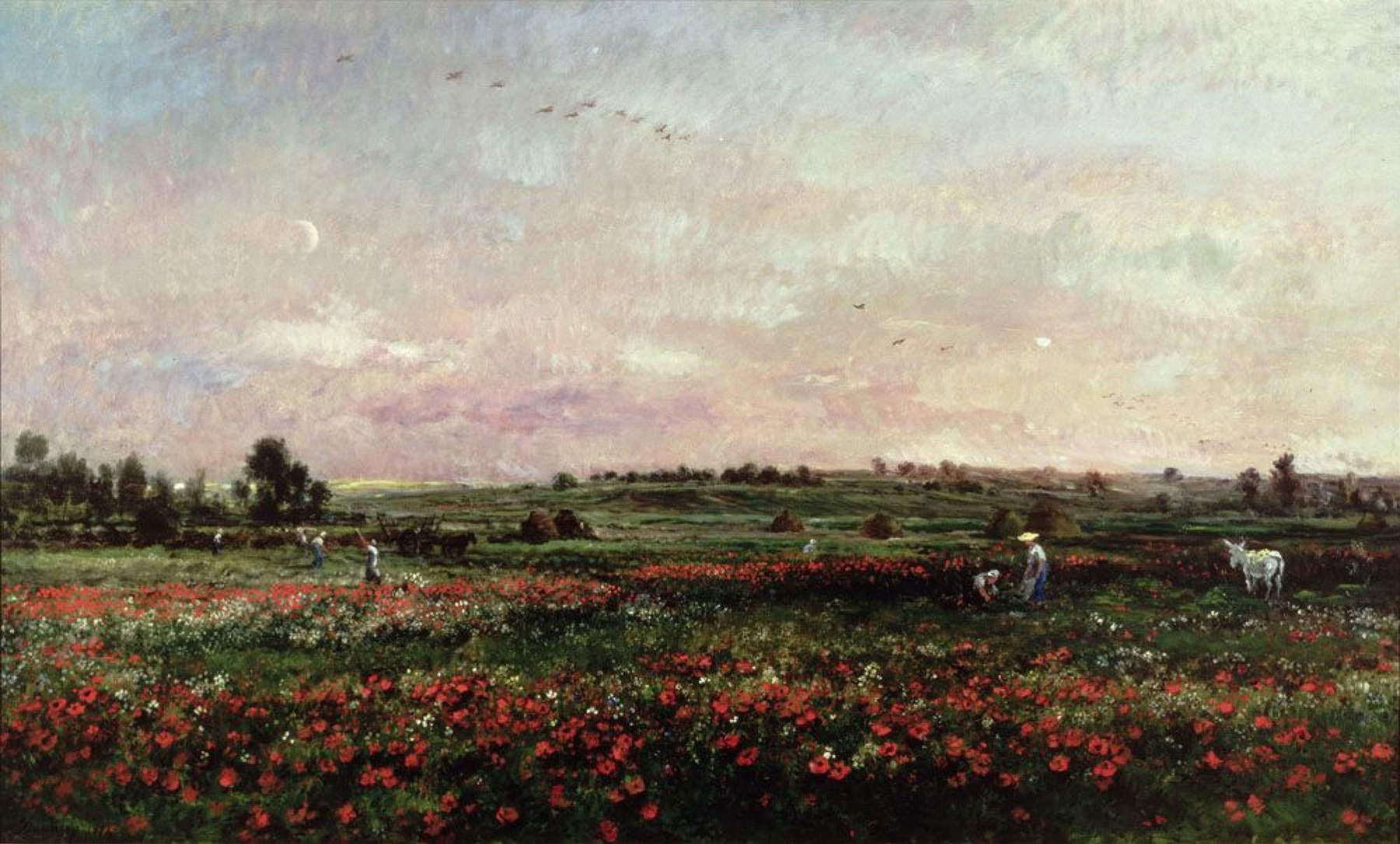

Kicking off with the Convergences section is that aforementioned gray zone intended to show how in reality there is a very blurred boundary between the Salon and the exhibition of the Anonymous Society, which is based onbeing accepted or rejected: presented here is a delicate pastel by Eva Gonzalès that was exhibited at the 1874 Salon, but at the same exhibition another of her paintings, which we can admire here, of a similar subject to Renoir’s Loggia, which the latter instead had every freedom to exhibit at the Impressionist exhibition, was rejected. Édouard Manet’s Masquerade Ball depicted by Édouard Manet was also rejected at the 1874 Salon, as it unambiguously presents the haggling between prostitutes and clients, while The Railway by the same author was exhibited, although the work, placed between a composition with a mythological theme and De Nittis’ Dans les blés, was derided by the public. Then there are artists such as De Nittis himself and Stanislas Lépine who exhibited both at the Salon and with the Impressionists, as can be seen from the captions of the works featured here. The next two sections, on the other hand, are intended to show how between the Salon of 1874 and the first exhibition of the Anonymous Society there was a convergence of themes: thus, as we can read in the captions, scenes of modern life but also landscape scenes were exhibited in both. Among these, one can see gathered together delightful watercolor works by Eugène Boudin depicting beach scenes, all of which were exhibited at the first Impressionist exhibition, as well as a painting by Degas depicting one of the most fashionable pastimes among the bourgeoisie of the time, namely horse racing, or Monet’s Poppies . Then there is Degas’s Ironing Woman, also shown at the Impressionist exhibition, while Ernest Duez’s Splendeur, which probably depicts a courtesan at the height of her career and dressed in fashion, contrary to what one might have thought, was accepted and exhibited at the Salon. Three works by Berthe Morisot of open-air scenes featured in the Impressionist exhibition, as well as some country landscapes by Camille Pissarro; at the 1874 Salon, however, is a large painting by Charles-François Daubigny, Fields in June, which offers bright colors and a strong contrast between the green of the vegetation and the red of the poppies, with a painting and light close to Impressionism. The artist actually from 1870 showed some interest in the future Impressionist painters, so much so that he put them in contact with Paul Durand-Ruel, their main dealer. Even Antoine Guillemet’s Bercyin December, shown at the Salon, could easily have been on display at the Impressionists’ exhibition because of the atmospheric effects and the play of light created through the clouds to give the feeling of winter cold.

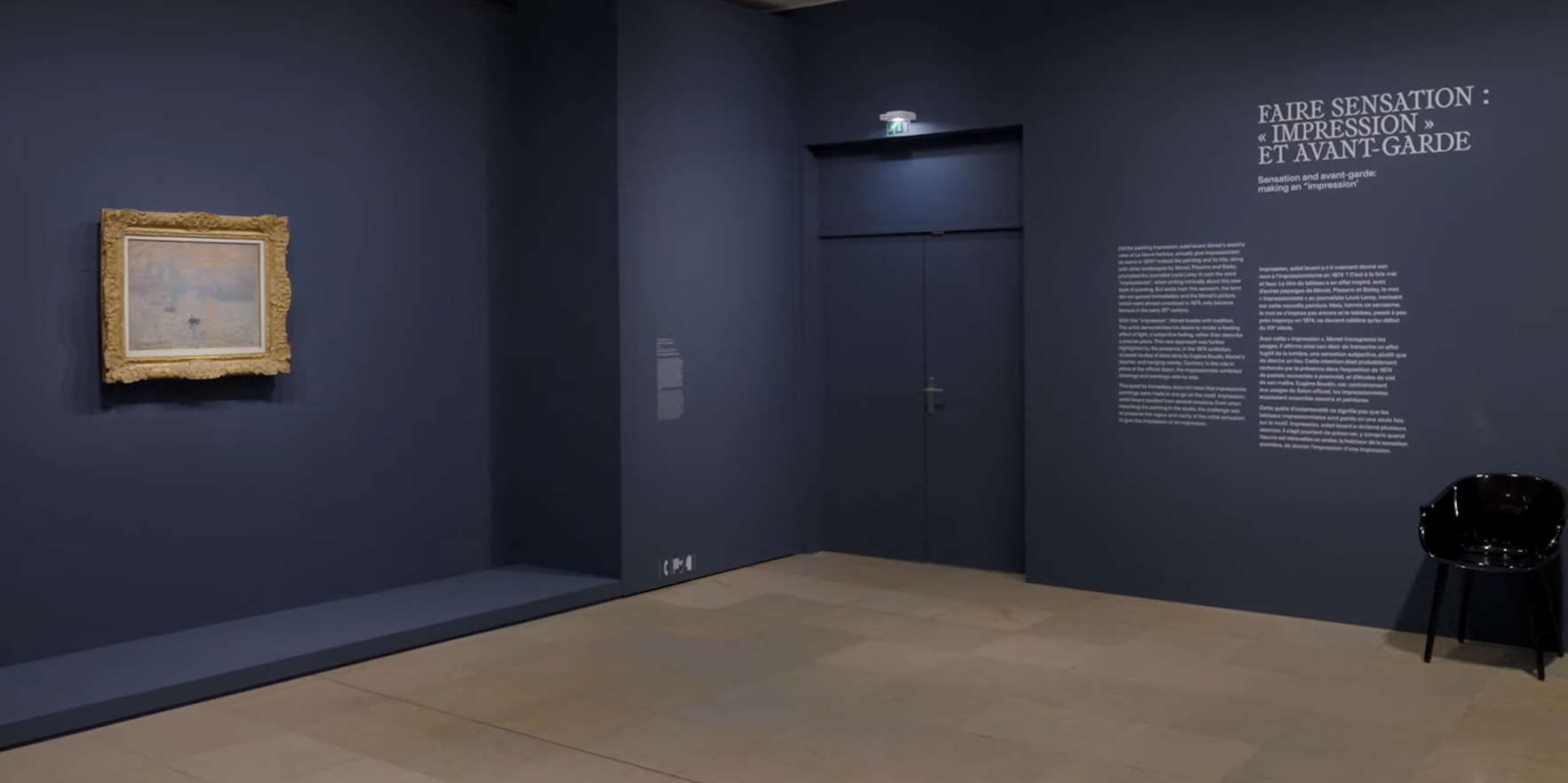

We then come to the penultimate section, where the curators decided to place Monet’s Impression, soleil levant, considered the painting that inspired the term “Impressionism,” used by journalist Louis Leroy in an article titled “The Exposition of the Impressionists” published in Le Charivari to sarcastically crush, referring precisely to Monet’s masterpiece, that first exhibition at 35 Boulevard des Capucines. The curators also placed the painting in dialogue with some pastels by Monet himself and Eugène Boudin depicting sky studies, as was the case at the Impressionist exhibition. The spark that coined the term “Impressionist” was thus Monet’s masterpiece, which within its title already contained part of the word, but the term was not really used from that time on to designate the artists of the Anonymous Society. Four days after Leroy’s article, critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary first used the word “impressionist” in a positive way; he wrote that they were “impressionists in the sense that they did not depict the landscape, but the sensation produced by the landscape.” Instead, it was in 1877, the first and only time, that the same artists of 1874 called their exhibition, their third, Impressionist. And the same year they gave to the press the journal L’impressioniste: journal d’art. It was precisely from this moment that they independently established the birth of a new movement. The third Impressionist exhibition opened on April 4, 1877, at 6 rue Le Peletier in Paris, and it was consciously the most Impressionist of all the editions that followed (five others in all), both in terms of the maturity of the project and from the point of view of organization and staging. Today’s exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay therefore closes with a section devoted precisely to the Impressionist exhibition of 1877, in which a number of works that participated in it are brought together here, such as La Gare Saint-Lazare, A Corner of an Apartment and Monet’s Turkeys , Gustave Caillebotte’s Peintres en bâtiment, some landscapes by Pissarro and Renoir, but above all two masterpieces by Pierre-Auguste Renoir stand out: The Swing and Bal du moulin de la Galette, the latter described by Émile Zola as the “capital piece” of the 1877 exhibition.

One leaves the exhibition halls already with one consideration: the exhibition event celebrating the 150th anniversary of that first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 is undoubtedly worth a trip to Paris, first because of the magnitude of the event and then because of the unprecedented slant that was chosen for an exhibition on Impressionism: not only the possibility of seeing so many masterpieces of the French movement brought together, but also having proposed the original comparison with the Salon that was held that same year, raising questions about the convergences between the two exhibitions usually considered to be at opposite ends of the spectrum. Also useful was the fact that in some rooms the catalog was made available to the public for free reference. The 1874 exhibition closed a month later with more than 3,500 visitors and with four works sold; the artists of the Anonymous Society could never have imagined at that time that they would arouse so much fascination even 150 years later. Their revolutionary and independent wind blew in the right direction, and here we are today celebrating one of the most innovative art movements ever.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.