When art and poetry were twins. What the exhibition "Painting and Poetry" at the Borghese Gallery looks like.

It’s hard to pay attention to the base when admiring Bernini’sApollo and Daphne , caught up in that marvel of marble, Apollo’s running, Daphne’s fingers becoming branches and laurel leaves, Daphne’s legs becoming a trunk, the nymph’s lightness, Bernini’s sensitivity to materials. The base is the element usually least considered, often not even bothering to photograph it: yet it is there that the meaning of the whole sculpture is to be found, the reason why a group with a pagan subject was showing itself in the villa of a cardinal in the early seventeenth century, and it is observing the base that one realizes how close the link between art and poetry was at the time when the language that, more than a hundred years later, some would call “baroque” triumphed. On the base of theApollo and Daphne can be seen a bizarre mask bearing a cartouche on which is stamped a moralizing couplet composed by Maffeo Barberini shortly before he ascended to the papal throne under the name Urban VIII: “Quisquis amans sequitur fugitivae gaudia formae / fronde manus implet baccas seu carpit amaras,” or “He who loves and pursues the joys of fleeting beauty, fills his hand with fronds and plucks bitter berries.” Barberini wrote his verses in 1620, five years before the Borghesian group was finished, but the circumstance did not prevent Bernini from sculpting those fourteen words in Latin as a commentary on the work, if the verses from the first book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses attached to the other side were not enough, verses that refer the relative to the literary source of the moment captured by the young sculptor’s chisel. Syntheses of art and poetry, works of art as lyrics, paintings and sculptures that reveal themselves to the relative with an immediacy equal to that of rhyming verse, compositions that seek to arouse the same sensations that the sight of a painting or a marble group is capable of releasing: seventeenth-century aesthetics hardly prescinds from this phenomenon, from the continuous exchange between image and written word that rereads the Horatian “ut pictura poësis” in a fluid, free, bidirectional sense.

The doors of the Galleria Borghese, the place where this synthesis is grasped the most in the world, open therefore to an exhibition, Poetry and Painting in the Seventeenth Century, curated by Emilio Russo, Patrizia Tosini and Andrea Zezza, which seeks to explore this exchange, which investigates the sophisticated legacy of one of the foundations of Baroque aesthetics, which traverses the entireentire biographical and literary vicissitudes of Giovan Battista Marino to share with a wide audience some of the most admirable results of this synthesis and to stitch around the figure of Marino that guise of de facto theorist that inevitably extends far beyond his verse the importance that his pen held for seventeenth-century culture. In his book The Aesthetics of the Baroque, Jon Snyder, a profound connoisseur of the intertwining of art and literature in the early seventeenth century, has written that Marino’s explicit interest in painting facilitated “the spread of his poetics and taste far beyond the limits of literary culture”, and this in spite of the troubled biographical events of the poet, presented in the exhibition with due detail, in spite of the ecclesiastical censure that fell on theAdonis, in spite of the thick anti-Marinist fringe that tried for most of the century to belittle his merits. Giovan Battista Marino’s critics substantially reproached him for his anti-classicism, sometimes quietly but more often with a certain vehemence, which even resulted in violent episodes: in 1609, in Turin, a rival poet of his, Gaspare Murtola, in order to settle the quarrels he had with Marino thought of shooting him: the attempt failed, Murtola was arrested, and Marino would .... benefit in terms of publicity. Marino himself was moved by the conviction that he wrote against any rule, and that his only rule was “to break the rules in time and place, accommodating himself to the current custom and taste of the century,” as he would write in a letter at the time of the publication ofAdonis, in 1624. And we are not just talking about breaking literary rules, we are not just talking about Marino’s seductive, bizarre, extravagant, excessive, inexhaustible poetry, that poetry that aimed at the deliberate slaughter of everything that had been classical poetry: decorum, balance, harmony, proportion. No: Marino’s operation transcended the field of poetry and invested that of the visual arts.

Certainly, interest in painting and sculpture must have oriented the poet’s ideas, and the exhibition, which kicks off in the Salone di Mariano Rossi, begins by offering the public a suggestion, that is, by establishing a sort of parallel between the host, Scipione Borghese, and Giovan Battista Marino himself, both cultured art lovers, both influential figures, both fine collectors, despite the fact that they did not run on good terms, on the contrary: the cardinal disliked the licenses that Marino, who was considered an obscene and lascivious poet, took with his compositions, and he did not fail to make his weight felt when, in 1623, the poet had to undergo a humiliating trial that brought him before the Inquisition and ended with a public abjuration (the pontiff at the time was Urban VIII himself). In the portrait by Frans Pourbous the young man who renders with acuity and precision the image of Giovan Battista Marino (and portrait that in the exhibition, a finesse of the fitters to which Ilaria Baratta draws the writer’s attention, is displayed next to the 1st-century A.D. Meleager that is usually found in Mariano Rossi’s Salon: at Marino’s time the sculpture was identified as an Adonis), an excellent loan coming in from Detroit and a work from 1619-1620, we see how Marino must have perceived himself at that time, at the height of his career, at the time of the composition of the Galeria (1619), namely, holding the book, flaunted as the cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus that Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy had granted him ten years earlier: haughty, almost contemptuous gaze, which is answered by the relaxed pose with elbow resting on the back of the chair, sober but fine clothes, the symbols of his success proudly displayed (the chain with the cross of merit pulled with his right hand was a license that only an over-the-top poet like Marino could allow himself). A year before Pourbus painted this portrait, Marino, in the Dicerie sacre, in addition to remarking on the role of painting and sculpture (“they delight the eye with beauty, sharpen the wit with artifice, recreate remembrance with thehistoria delle cose passati, et incitano il desiderio alla virtù con l’esempio delle presenti”), he established a kind of canon of artists who, in his view, represented the pinnacle in their respective ’specialties,’ we might say: Parmigianino in “grace,” Correggio in “tenderness,” Titian in heads, Bassano in animals, Pordenone in “pride,” Andrea del Sarto in “sweetness,” Giorgione in shading, Francesco Salviati in drapery, Veronese in “vagueness,” Tintoretto in “prestezza,” Dürer in “diligence,” Cambiaso in “practicality,” Polidoro da Caravaggio in battles, Michelangelo in foreshortenings, and “Rafaello in many of the aforesaid things.” many of them are duly represented in this first section of the exhibition. For Marino, painting and poetry shared the same conceptual plane: they were closely related arts, as Vasari had already established several decades earlier (“painting and poetry use the same terms as sisters”) and as Francesco Furini would also recognize by painting in 1626, that is, a year after Marino’s death, a painting in which the personifications of the two arts embrace and kiss each other to sanction an aesthetic and theoretical union with what can be considered a manifesto of seventeenth-century culture.

The fellowship between the two arts can be grasped with immediacy in the long theory of works that the exhibition squares off in the rooms on the first floor of the Galleria Borghese to compose a sort of ideal collection inspired by Marino’s Galeria , that is, the enterprise composed of 624 lyrics (mostly madrigals and sonnets), initially imagined to be published with ample illustrations, celebrating the works Marino had seen in the collections he frequented. The selection made by the exhibition, though with a few slight departures from context (for example, Cavalier d’Arpino’s Diana and Actaeon is not in the Galeria, where the only painting on the subject is by Bartolomeo Schedoni), and strong however of a lunge on Caravaggio, who had relations with Marino to the point of being praised by the poet, offers a summary of Marino’s Galeria , from Titian’s Penitent Magdalene arrived on loan from the National Museum of Capodimonte (“fu del Signor seguace e cara ancella, / e quanto prima del folle mondo errante / tutto poscia di Christo amata amante”) to Giovanni Battista Paggi’s Samson and Delilah (“Paggi, quel tuo Sanson così ben dipinto [...] / specchio esser verace, ancor che finto, / de l’man, who, flattered and enamored / by vexatious flesh, is then mocked / in such a way, that he remains extinguished”), from Saint Peter in marble by Nicolas Cordier (“I am Stone, I am Peter / in whom the high Architect / of his heavenly and holy construction / founded the sublime plant. / And if well fragile glass you seemed to the assaults, I am Stone in effect, / then that new Moses draws me from the lights / two living rivers”) to Rubens’ Leander (“Where do you take / Nymphs of the sea, in merciless pity, the funeral coffin / that the amorous fire and ’vital light / among the turbid spume together has extinguished / of your cruel and barbarous element?”).

What is very evident from Marino’s compositions is the fact that poetry for him was not a kind of accompaniment to the image, nor, even less, was it to be given a descriptive function, we might say: Marino was concerned with igniting with verse the emotions, the sensations that the relative experiences in the presence of a work of art. Just as the sight of a painting or sculpture arouses an immediate reaction in the observer, so must painting. “Although always in different ways,” writes Carlo Caruso in his essay published in the exhibition catalog, "the Galeria ’s compositions evoke the excitement aroused by the encounter with the work of art [...]. Surprise, uncertainty, excited questions, sometimes confusion (or even pleasure mixed with discomfort), illusions and disillusionment, bewilderment, admiration, aphasia are among the most frequently ’recorded’ reactions." That Marino was moved by a theoretical intent, unstated, and perhaps even not fully felt, but nonetheless alive and pulsating, is also realized by the subdivision of the Galeria, which in fact established the modern canon of painting genres: “fables” (i.e., paintings with stories of profane or mythological subjects), “historie” (stories of sacred subjects), portraits (of princes, captains and heroes, tyrants, privateers and “scelerati,” pontiffs and cardinals, “necromancers and heretics”, orators and preachers, philosophers and humanists, historians, jurists and physicians, mathematicians and astrologers, Greek poets, Latin poets, vernacular poets, painters and sculptors, lords and men of letters, burlesque portraits, women “beautiful, chaste, and magnanimous,” women “beautiful, impudent, and chosen,” women “warlike and virtuous”) and “whims,” or fantasy subjects.

It is well known to those familiar with the arts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that, from Vasari onward, art no longer suffered any inferiority complex with respect to letters: with Giorgio Vasari the modern equivalence between the visual arts and poetry was established, an equivalence that no one, at the dawn of the seventeenth century, would have dreamed of questioning. On the contrary: if anything, a more or less conscious conviction of the gap that poetry suffered in relation to the visual arts spread. “The prestige attained by painting thanks to our Renaissance masters,” Mario Praz wrote in 1970, in a passage quoted by Andrea Zezza, “assured [painting] victory in the comparison with its sister poetry, a victory to which the poets’ efforts to compete with the brushes in their sensuous descriptions give eloquent testimony.” And it is not just a competition: images become sources of inspiration for poetry. The culture of the Renaissance masters was proof that it was possible to stop considering the scholar as the sole repository of the theoretical project of a work of art, the sole custodian of the sources of the painted or sculpted image. The poet not only engages in a competition with painting or sculpture: the poet, while continuing to wear the guise of the theorist, begins to write inspired by works of art. This is one of the most innovative achievements of the Marinian revolution. Without this assumption, one could not explain not only some of Marino’s compositions that follow works of art (an example is the madrigal Che fai, Guido, che fai?, initially dedicated to Giovanni Battista Paggi’s Strage degli Innocenti, unfortunately torn to pieces in the twentieth century, a fragment of which can be seen in the exhibition, and then, however, changed in favor of Guido Reni’s counterpart painting, simply by changing the vocative), but probably not even a masterpiece such as theAdonis that has also been read by virtue of its relationship to images Marino may have seen, such as Bruegel’s Allegories of the Five Senses , which may have suggested to Marino the three cantos of theAdonis dedicated to the celebration and exaltation, precisely, of the five senses. TheAdonis, writes Emilio Russo, is after all “a work built almost like a collection, the symbolic masterpiece of the Baroque in poetry; a work kneaded with figurative matter, following Marino’s great passion for art: not by chance, in the years in which he wrote the poem, Marino sent several contemporary artists many requests for paintings and drawings centered precisely on this myth.”

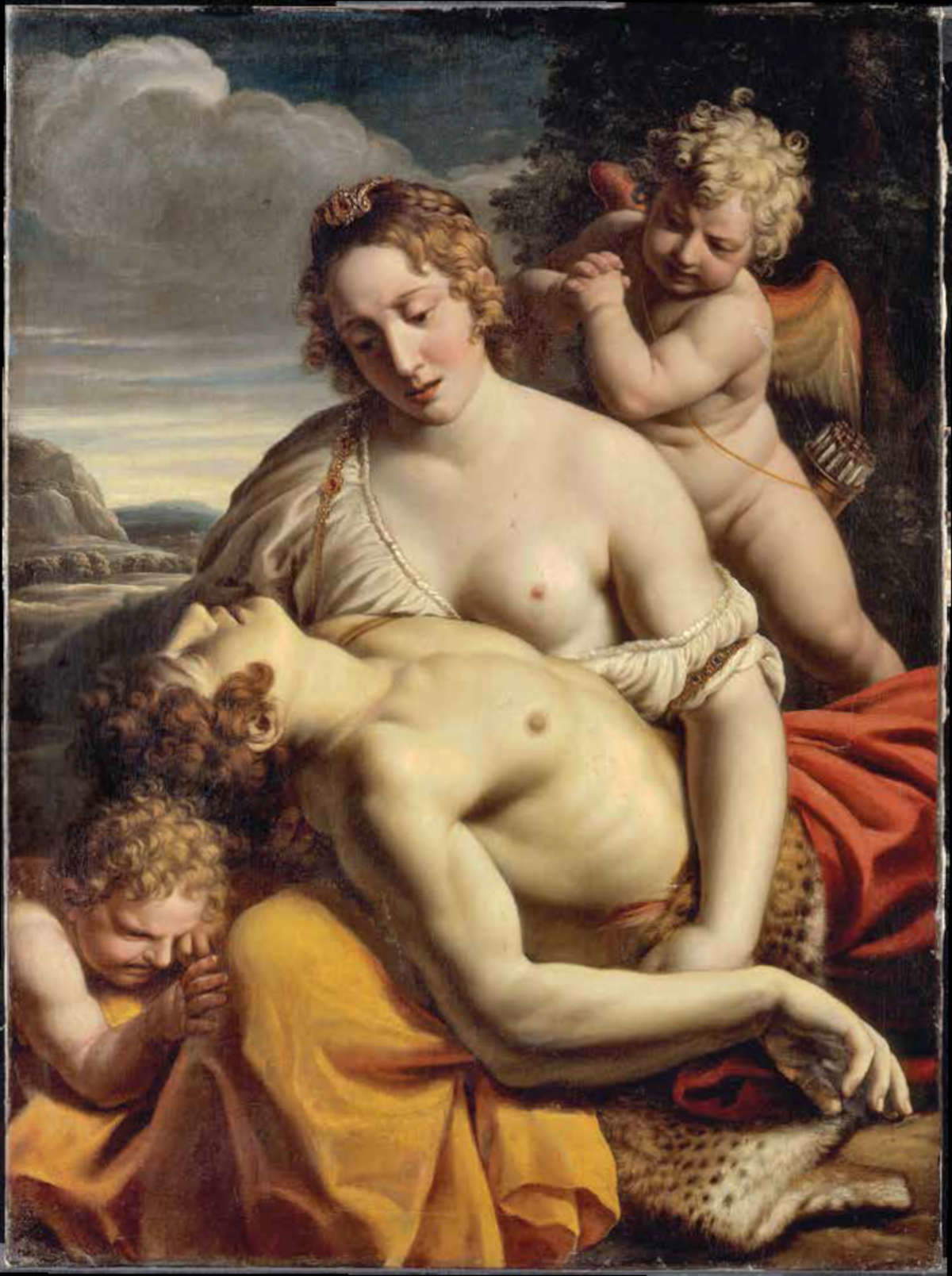

Of course, there was no shortage of painters who were seduced by Marino’s verses: proof of this is the Venus with Dying Adonis by Alessandro Turchi, who was a friend of the poet and who painted a work indebted to his verses, since Venus’s lament over the body of dead Adonis is a theme of Marino’s invention, which does not appear in classical mythology but inspires Marino with some of the most poignant verses of his very long poem: Turchi’s painting is one of the high points of the section devoted to theAdonis, as well as one of the paintings that most adhere to Marino’s verses. A formal and substantial adherence would then come a few years later from one of the greatest painters of the seventeenth century, Nicolas Poussin, who can be considered a sort of creation of Cavalier Marino, since it was his close friendship with him that determined “the poetic coloring of his work,” writes Mickaël Szanto: Marino discovered his talent in the Paris of Louis XIII, convinced him to follow him to Rome (Poussin, in 1625, when he arrived in the Urbe, had just turned 30), and initiated him into the knowledge of ancient and modern culture that was decisive in Poussin’s poetics. If the Death of Chione bears witness to their shared interest in classical literature, the Lament over the Body of Dying Adonis is the work “that perhaps better than any other,” Andrea Zezza argues, “adheres to the complex layering of meanings, feelings and tones of the Marinian verses dedicated to the death of thehero, where the tragic event is described in lyrical and sensual tones, but also with a wealth of allusions to deeper and more hidden themes, such as the anemone that is born from the balm poured by Venus as an emblem of rebirth.” There is also no lack of those Christological allusions that had been among the reasons for Marino’s problems with the Inquisition, and the pattern works even in reverse: the Lamentation over the Dead Christ at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich is filled with pagan elements, beginning with the setting and ending with the two putti weeping over the death of Jesus (the same ones who, in Marino’sAdonis , weep for the mythological hunter).

Poetry and painting, for Marino, were much more than Vasarian “sisters.” They were “dear twins” born of a single birth, similar in everything, so much so that poetry could be called “talking painting” and painting “taciturn poetry,” of poetry is proper the’mute eloquence, of painting the eloquent silence, both tend to the same end, “that is, to delightfully pasture the animi humani, et con sommo miacere consolargli,” and their only difference lies in their means: one imitates with colors, the other with words. What Giovan Battista Marino writes in the second part of the Dicerie sacre is more than a kind of programmatic writing, more than an ideal manifesto: it is the very substance of his poetry, a substance that imbues Baroque aesthetics, a substance that shapes the culture of a century, a substance that covers every nook and cranny of the Galleria Borghese, a place more than any other suited to host an exhibition as cultured, elegant, and complex as Poetry and Painting in the Seventeenth Century.

It has often been said on these pages that it is difficult to organize exhibitions at the Borghese Gallery, given the conformation of the museum, which hardly lends itself to operations that are not small in scale and demonstrate little compatibility with the place. We are not just talking about questionable operations such as those that in the past have brought works by twentieth-century or contemporary artists to these halls, with exhibitions that clashed with the context and clung to staggering justifications: we are also talking about exhibitions that are more centered on the Borghese Gallery, but with heavy and impactful set-ups (perhaps the best-known example is that of last year’s not exactly memorable exhibition on Guido Reni). This year, albeit with a few hiccups (the set-up of the first section, in the Salone di Mariano Rossi, perhaps the most difficult of the entire Gallery, will not be remembered among the best), the public is offered a more delicate review than has been seen in the past, an exhibition largely composed ofworks that are part of the permanent collection, and where the dialogue between the works in the collection and those on loan is intended to evoke, through a real collection, namely that of Cardinal Borghese, a collection as imaginary as it is real, the one that Marino had described in his Galeria. A singular idea, that of uniting two enemies, two opposing personalities, two personalities in their own way extreme, in the sign of art: it is one of the subtexts of the review, as if to say that it was around the visual arts that all cultural debate revolved at the time. And there is no doubt, however, that from the clash, in the long run, it would have been Marino who would have emerged the victor: despite the doggedness of the Inquisition, Marino’s poetry would have plowed a very fertile soil, destined to produce very valuable fruits, starting with that same Poussin who perhaps would not have been the same painter without having known Giovan Battista Marino. A whole century would have been different if Giovan Battista Marino had not been there.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.