The record belongs to Julius von Schlosser, a distinguished pioneer of the Viennese school of art history: he was the first to take an interest, and to do so with a systematic measure, in the historiated caskets produced in the fifteenth century by the Embriachi workshop, a prolific atelier implanted in Venice at the end of the previous century by a Florentine, Baldassarre Ubriachi, who in spite of his name was lucid in promoting his activity by responding with constant diligence to a fashion he himself had helped to spread, and by working to ensure that his workshop survived him. Schlosser started from the specimens preserved in the imperial collections of Austria to initiate research that also aimed to classify the caskets (he divided them into five classes) and that would lay the groundwork for modern interest in these singular objects of “industrial art,” it was said at the end of the 19th century (“applied arts,” and more specifically “decorative arts” we say today instead), made mostly with the technique of the pastille, a mixture of plaster, glue and marble powder with which figures were modeled, often using metal dies, which were then mounted directly on the gold leaf that served as the background. An interest perhaps not constant, but one that has nevertheless been kept alive by the good offices of the collectors who have collected the boxes (some have gathered dozens of them) and of the scholars who have examined them with increasing care, from Walter Leo Hildburg to Patrick De Winter, who exactly forty years ago published a study in which he rekindled attention to A little-known creation of Renaissance decorative arts: the white pastiglia box, through Claudio Bertolotto, author four years ago of a ponderous monograph on the subject, to Pietro Di Natale, who has curated this year, at the Palazzo dei Diamanti, the first comprehensive exhibition ever devoted to this genre of objects.

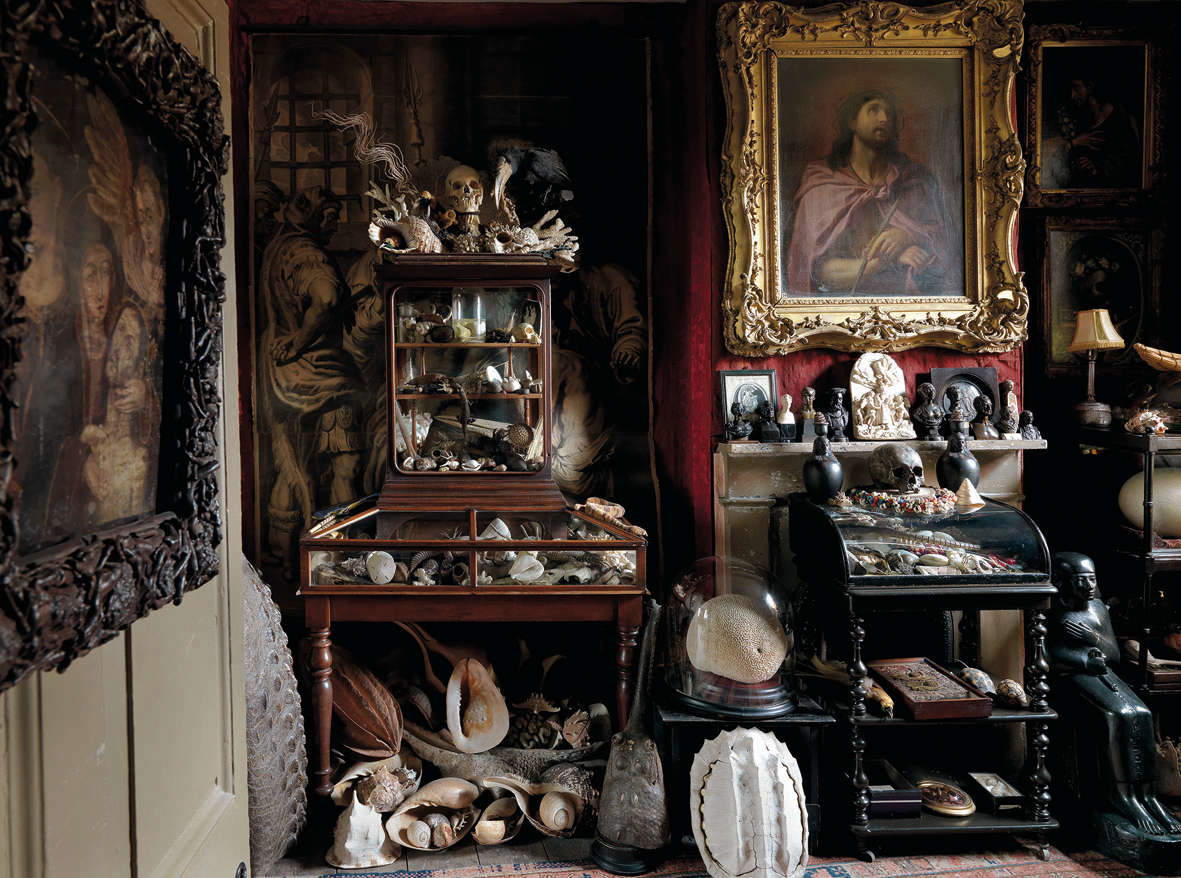

Entitled Mirabilia Estensi. Wunderkammer, you can visit it until July 21, and it brings together, in the two exhibition rooms of the Benvenuto Tisi Wing of the Palazzo dei Diamanti, a fair number of pastille caskets (about thirty in abundance) that accurately describe the spread of this fashion in northern Italy in the 15th century, and in particular the role played by the Ferrara workshops, which were able toelaborate forms, models, and styles capable of inflaming the passion for antiquity (for the themes with which the caskets were decorated were almost always taken from the history and myths of antiquity) of wealthy collectors who asked for them, either for themselves or, as was typical, to make wedding gifts. It is not common to find exhibitions devoted to these objects, and those that have been organized in the past have mostly had a vertical slant: they were either centered on caskets from individual collections, or focused on the products of a single workshop (and always the same one, that of the Embriachi). The Ferrara exhibition therefore provides a rare opportunity not only to appreciate objects that are difficult to admire (sure, there are museums that have them in their collections, such as the Museo di Palazzo Venezia in Rome, although most stay in private collections and collectors keep them as relics), but also to see, all together, objects made by different workshops. On the walls, all around, the photographs Massimo Listri took of a series of Wunderkammer around Europe: partly because it was not uncommon for objects like these, or similar containers, once they had lost their practical use (they could be jewelry boxes, or boxes to hold letters and rosaries, or even personal care tools, such as mirrors, combs and so on, and not infrequently were scented with ’essence of musk), became wonders to be displayed in cabinets of curiosities, and some because in the mid-15th century the production of caskets, especially from Ferrara, was to some extent stimulated and nurtured by a curious, versatile and often even voracious collectorism, which did not disdain the applied arts alongside the products of the hand of the great masters, or rarities from the natural world.

The itinerary opens with a box from the Bottega degli Embriachi owned by the Fondazione Cavallini Sgarbi: it is decorated on the sides with figures caught in the act of conversing with each other, against the background of stylized saplings that are a sort of trademark of the Embriachi, just like the geometric decorations on the lid, with more or less elaborate checkerboard motifs of lozenges. On the sides, the figures holding shields show that the object must have been a wedding gift: the shields bore the coats of arms of the bride and groom. This model, with its rectangular case covered with plates of bone (a material that came to replace ivory at a time when the precious proceeds from elephant tusks became less and less available on the market), on which craftsmen carved their figures, and the lid, which had the shape of a pitched roof, would later be imitated by other workshops that, on the back of the success of the caskets, would compete with the Embriacs. For example, another Cavallini Sgarbi casket, smaller than the one that opens the exhibition, dates from the first thirty years of the fifteenth century, and presents motifs similar to those of the Embriachi: the higher degree of stylization of the saplings and the slightly less elaborate conduction of the figures nevertheless suggest the execution of a workshop that emulated the caskets of their competitors.

On the other hand, the showcase alongside exhibits a large nucleus of caskets entirely decorated with geometric motifs, typically interwoven: one of these, preserved in Ferrara in the Palazzina Marfisa d’Este, shows a refined Carthusian workmanship (a complicated inlay of wood that was obtained by inserting decorative elements of wood or even of other materials, previously shaped, inside a base that was also worked so that the inserts would fit perfectly: one can understand why even today the adjective “Carthusian” indicates a work that requires care and patience), and is marked, writes in the exhibition catalog Francesco Traversi, “on mathematical modules, revealing a philosophical wisdom in the ability to interweave the motifs of the chessboard, arabesques and the Christian cross.”

Far more substantial, however, is the group of caskets decorated with motifs from ancient history, which in the exhibition is opened by an exceptional piece, attributed to the “Bottega di Andrea Mantegna” already by De Winter on the grounds that the Roman triumphs that adorn this unique cylindrical-shaped box, the only one in the exhibition, are reminiscent of Mantegna’s Triumphs , so much so that De Winter himself speculated on some involvement by Mantegna in the design of the decoration. A splendid object in wood, pastille and gold leaf, it presents a continuous decoration that dreams of parades of ancient Rome, opening up space in the exhibition to a reverie that was evidently common to so many collectors of the time, as well as to so many artists, Mantegna first. Here then is the casket from the Museum of Palazzo Schifanoia, with on its front a depiction of the legend of Marcus Curtius, the Roman hero who threw himself and his horse into a chasm, sacrificing himself to save Rome, and who returns often in the caskets of the time: we find him, for example, along with Muzio Scevola, in the casket produced by the Bottega di Amor-Ecouen, which on one of the short sides bears the figure of a building decorated on the outer walls with an ashlar in which Traversi wished to recognize that of the Palazzo dei Diamanti (“attesting once again to the pertinence of the production to the Ferrara context”). Here are the sumptuous, overcrowded and pompous caskets of the Bottega dei Trionfi Romani, including historical scenes (Lucretia’s suicides, Trajan’s justifications and so on) and mythological ones (such as Orpheus taming animals), without neglecting also elaborate decorations with phytomorphic motifs, such as the one that adorns the entire case of the “Cofanetto delle maschere,” one of the most interesting specimens of the entire exhibition. Here are the more restrained but no less marvelous creations of the Bottega dei Temi morali e amorosi, which often draws from myth: one casket takes us to an aquatic world where caravels proceed on the sea, a theme indeed quite recurrent in Ferrara production as it is inferred from works visible in the city (such as Lorenzo Costa’s Argonauts ), and some female figures party on small boats.

Not infrequently, the caskets mixed themes of different natures: for example, one of the products of the Bottega dei Temi morali e amorosi (not to be ruled out, it should be specified, that the products of this atelier may in fact be a new “line” of the Bottega dei Trionfi Romani) shows on one side the mythological tale of Pyramus and Thisbe, and on the other the biblical story of Susanna and the Old Men. The depiction of these episodes, Traversi notes, was intended to “elevate-because of its moral values and culture for antiquity-the respectability of its possessor,” another reason why historiated tablet caskets had wide success in fifteenth-century Italy. Prominent then for its distinctiveness, toward the close of the itinerary, is the singular piece from the Cleveland Casket Workshop where the scenes (the beheading of the son of Manlius Torquatus, the Horatii and Curiatii, and parades of warriors and enthroned figures), in addition to being resolved against the backdrop of groves in which the trees are neatly placed in rows and well spaced, are also framed within architectural frames that are far more elaborate than those of earlier productions. Closing the tour is another unparalleled piece in the exhibition, a circular casket decorated on the case with elements in the shape of stars and flowers, and on the lid with a harpy and two ichthyocapres: the most striking feature of this piece, attributed to craftsmen from the Moral and Amorous Themes workshop (with an eye, however, toward the Cleveland casket workshop), beyond theexceptionality of the decoration, lies in the singularity of the form and the curious circumstance that the lid is slightly less tall, and certainly more decorated, than the case.

![Craftsmen close to those working in the Bottega dei Temi morali e amorosi, Casket with Marco Curzio [recto], Warriors fighting on an elephant [right side] (early decades of the 16th century; wood, gold leaf and pastille, 9.8 x 12.8 x 8.8 cm; Ferrara, Museo Schifanoia, Gift of the Brunello family in memory of Marco) Craftsmen close to those working in the Bottega dei Temi morali e amorosi, Casket with Marco Curzio [recto], Warriors fighting on an elephant [right side] (early decades of the 16th century; wood, gold leaf and pastille, 9.8 x 12.8 x 8.8 cm; Ferrara, Museo Schifanoia, Gift of the Brunello family in memory of Marco)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2657/cofanetto-con-marco-curzio.jpg)

![Moral and Amorous Themes Workshop, Casket with City View [right side] (third-fourth decade of the 16th century; wood, gold leaf and pastille, 7 x 14 x 7.5 cm; Private Collection) Moral and Amorous Themes Workshop, Casket with City View [right side] (third-fourth decade of the 16th century; wood, gold leaf and pastille, 7 x 14 x 7.5 cm; Private Collection)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2657/cofanetto-con-veduta-di-citta.jpg)

![Cleveland casket workshop, Casket with Enthroned Figures and Warriors [verso] (early decades of the 16th century; wood, gold leaf and pastille, 16.7 x 40.2 x 27.5 cm; Private collection) Cleveland casket workshop, Casket with Enthroned Figures and Warriors [verso] (early decades of the 16th century; wood, gold leaf and pastille, 16.7 x 40.2 x 27.5 cm; Private collection)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2657/bottega-del-cofanetto-di-cleveland-cofanetto.jpg)

It is interesting to note that much of the production of the historiated caskets in pastille can be traced back to the time of Borso d’Este’s rule over Ferrara, so much so that the city would become one of the largest, if not the largest ever, of the centers of production of these objects, with an activity destined to last for a long time, well into the sixteenth century. This was mainly due to the peculiar interest that the Este family had in these objects, an interest that was probably unparalleled at other courts of the time. And it is curious to note that also from Ferrara, it may be said, an enduring passion developed that had to do with the forms that art collecting took from the 16th century onward.

The Este cultivated a strong passion for these objects: in the mid-15th century the Breton Giovanni Carlo da Monleone, master of pastille decoration, was active at court, and it is attested that artists such as Cosmè Tura and Giovanni d’Alemagna also devoted themselves to painting caskets. This interest was later exported to Mantua when Isabella d’Este, daughter of Hercules I and Eleanor of Aragon, married Francesco II Gonzaga in 1490: The marquise’s collection included, writes Pietro Di Natale, “caskets and boxes of silver, crystal, ebony, ivory, and inlaid wood,” all gathered “in the Corte Vecchia of the Ducal Palace, in the Studiolo, embellished with paintings by Mantegna, Perugino, Lorenzo Costa and Correggio, and especially in the Grotta, where artistic and natural rarities were displayed both inside cabinets and lined up on frames.” On these cabinets one could admire those Wunderkammer curiosities that accompany, on the walls of the rooms of the Palazzo dei Diamanti, the story of the exhibition. And the caskets themselves, as anticipated, became objects for display. It was precisely “the eclectic character of the vast Isabellian collection and the intermingling of works [...] in the Grotto,” Di Natale adds, “that would be distinctive elements of that type of princely collection, widespread in Central Europe as early as the early 16th century, called Wunderkammer, because it was formed essentially of pieces selected and grouped together with the intention of marveling those who were fortunate enough to admire them.” The historiated caskets would later become “significant pieces of these physical and symbolic ’spaces.’” From Ferrara to the collections of the finest collectors interested in hunting down the most precious and singular rarities. Still in the present day.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.