We can be heroes, just for one day. David Bowie, La Spezia

Look up here, I’m in heaven / I’ve got scars that can’t be seen / I’ve got drama, can’t be stolen / Everybody knows me now. These are the words with which David Bowie decided to open Lazarus, his last single, released a few days before his death. A sort of spiritual testament, a tormented slow in which the great British artist seems to want to draw the sums of a career that lasted almost half a century, which led him to touch the heights of international success with music that was refined and capable, though without inventing anything, of evolving continuously, of reworking cultured suggestions from different sources, of bringing new life to what he had already experimented with. Because, as we know, an artist’s flair cannot be judged solely by his or her ability to break new ground: an artist can find his or her originality, and thus the reason for his or her art, even in revisiting. David Bowie’s elegant art should be read in this sense: and until June 19 this reading is facilitated by an exhibition of photography.

|

| The entrance to the exhibition David Bowie & Masayoshi Sukita: Heroes |

David Bowie & Masayoshi Sukita: Heroes is in fact the exhibition celebrating the singer on the premises of the Fondazione Carispezia in Via Chiodo (La Spezia). The exhibition aims to retrace much of David Bowie’s artistic journey, thanks to the images of Masayoshi Sukita, one of the most highly regarded international photographers in the music industry: in addition to David Bowie, he has worked with stars such as Billy Idol, Iggy Pop, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, Joe Strummer, Cindy Lauper, and Marc Bolan. Sukita and Bowie met precisely because of the “indirect” help of Marc Bolan, the legendary lead singer of T-Rex: the group that, we can say without venturing too far, invented the glam rock that would have a considerable influence on Bowie himself. To be clear, T-Rex are those of 20th Century Boy, Hot Love, Bang a gong and many other hits carved into the hearts of rock lovers. Sukita traveled to England in 1972 specifically to photograph T-Rex: however, his attention was also caught by the Bowie phenomenon, a singer the Japanese photographer had never heard of. Sukita sees a promotional billboard for The man who sold the world, David Bowie’s third album, released in 1970: so he decides to go see him live. The concert he attends is but the beginning of a friendship destined to last for decades to come.

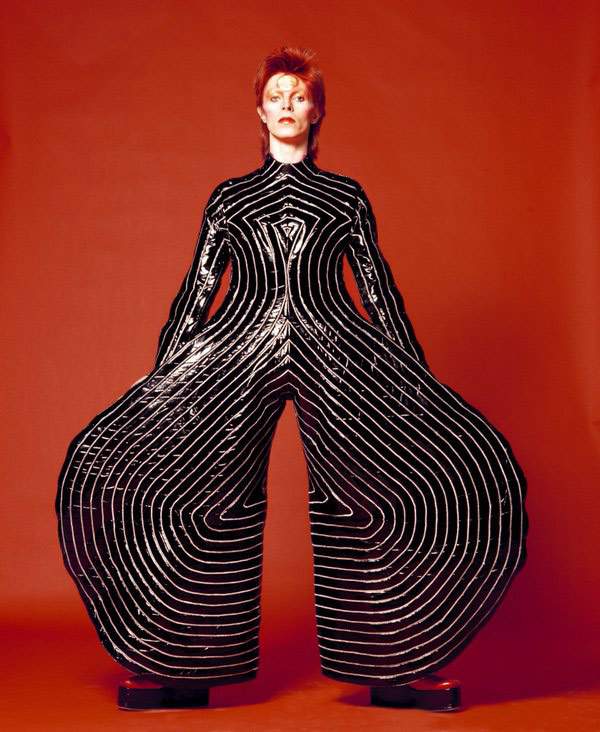

This is where the story told by the Carispezia Foundation starts: from the glam years, from Ziggy Stardust with his costumes inspired by science fiction (but also by Japanese tradition: inspiration from Eastern art is constant in David Bowie’s output) and with his androgynous look, which caused a sensation at the time and which, in turn, was a kind of reflection of kabuki, a form of theater, born in seventeenth-century Japan, in which female parts were also played by men. Marc Bolan’s winking sensuality is, in essence (and trivializing), revisited from a spatial perspective, and with an eye to the East. Photo-symbol of this first section (we can divide, broadly speaking, the path of the exhibition into four areas: the one devoted to glam is the largest) is Watch that man III, which also stands out in the giant picture that greets visitors at the entrance. The strong link between David Bowie and Japanese art is here sealed by the large, whimsical suit made by Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto, tailored especially for the 1973 Ziggy Stardust tour.

|

| Masayoshi Sukita, Watch that Man III (1973). © Masayoshi Sukita, 1980 |

We then pass through the central hall, where several panels bearing phrases by David Bowie and Masayoshi Sukita stand out in addition to almost monumental-scale reproductions of some of the exhibition’s most important images. Significant is the one in which the photographer says, “It was in 1972 that it all started. And to this day I still keep looking for David Bowie”: a statement that testifies to us how elusive and enigmatic David Bowie’s character was, despite the fact that there was a relationship between him and Sukita that went even beyond professional collaboration. Nearby, we find a statement by David Bowie that may sum up the meaning of his art: “I believe that my task, as an artist, consists not only in expressing my work. I have always wanted, more than anything else, to make a contribution to the culture in which I have lived.”

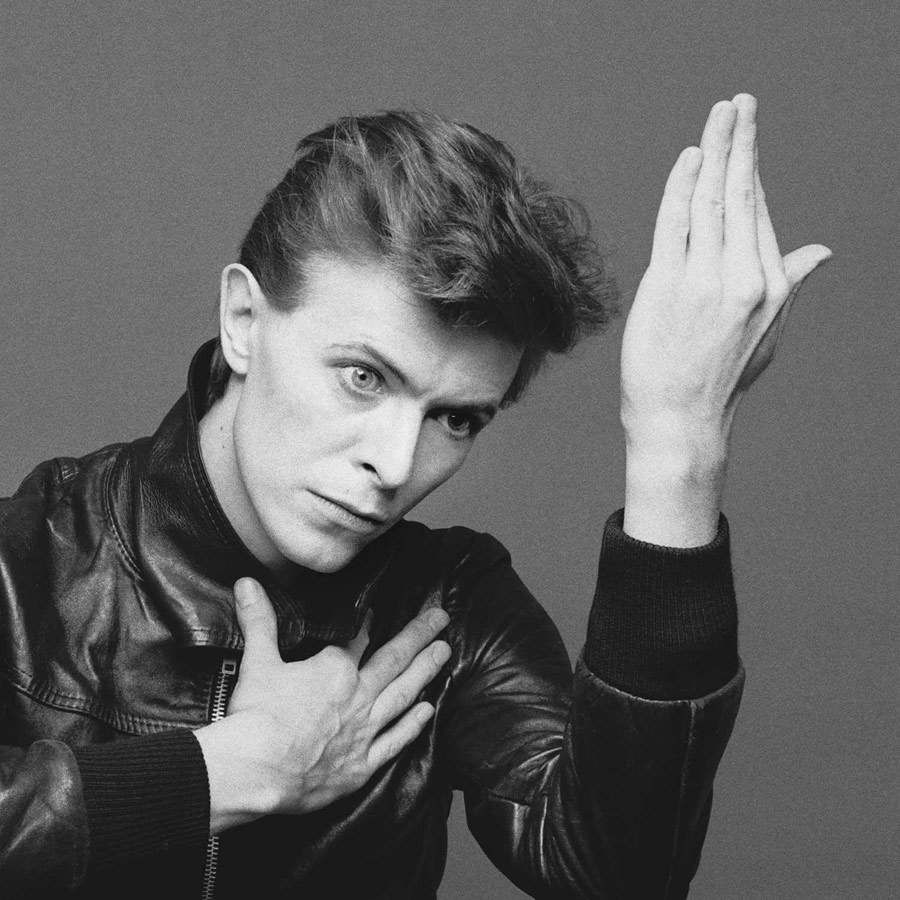

Following the chronological path of the exhibition, we come to the late 1970s: a small room, which we might identify as the second section of the itinerary, is thus dedicated to the late 1970s. David Bowie had already been to Japan in 1973, for the first time, during theAladdin Sane Tour, famous because on the last stop (at the Hammersmith Odeon in London, on July 3) the artist would definitively cease the panny of Ziggy Stardust, of the man of the stars (if we exclude the brief return in 1980, of course). Thus, a new phase of his career opens. In 1977, the British singer is off to Japan for a series of concerts he would give together with Iggy Pop, who was in the throes of a drug abuse crisis at the time: David Bowie is among the few to help his American colleague. Bowie calls Sukita (with only one day’s notice, by the way) to ask him to photograph him and his friend during a short session: the time to get the two singers to pose and take pictures (and to remember to bring the leather jackets that Bowie specifically requested) is barely an hour. Some time later, the two singers would ask the photographer for permission to use those images: they would become the covers of two albums, David Bowie’s Heroes and Iggy Pop’s The Idiot .

|

| Masayoshi Sukita, Heroes (1977). © Risky Folio, Inc. Courtesy of The David Bowie Archive |

We can be heroes, just for one day: perhaps David Bowie’s most famous song needs little introduction. An avant-garde rock that transports us to the Berlin of the wall, but with a sense of strong hope: because “shame is on the other side,” because passionate kisses can outweigh the sound of guns, because love cannot be hindered by any barrier (and walls can be broken down): we can be heroes, just for one day. Sukita’s photography is rooted precisely inGerman Expressionism (Bowie had moved to Berlin in 1976): the reference in particular (by David Bowie’s own admission) is to Erich Heckel and his 1917 work Roquairol , whose title bears the name of a tragic character from a novel by the German writer Jean Paul(nom de plume of Johann Paul Friedrich Richter). Bowie himself was a painter, himself greatly influenced by German Expressionism: a beautiful painting by Otto Müller kept at the Brücke-Museum in Berlin, known as The Lovers within the Garden Walls, which depicts a pair of lovers embracing between the walls dividing two gardens, may have very closely inspired the composition of Heroes. It is just too bad that in this section the exhibition gets a little lost, and does not allow the visitor to catch these references, despite the rather comprehensive, almost exhaustive captioning apparatus (which is not very usual for a photography exhibition).

|

| Masayoshi Sukita, The same old Kyoto (1980). © Masayoshi Sukita, 1980 |

The exhibition continues with images from the trip to Kyoto in 1980. This third section documents perhaps the least known of the events narrated during the exhibition. Above all, it is a section that gives us back a David Bowie decidedly closer to our own feeling, a more “human” David Bowie if you will, a David Bowie who, despite his fame, has no qualms about traveling without any protection and, indeed, taking the trouble himself to buy tickets for his friend Sukita at a time when the photographer was carrying his bulky equipment: the anecdote is featured on a wall next to the photograph depicting David Bowie at Kyoto Station, near the tracks, holding a cigarette in his mouth with a natural expression, almost jerking it toward the viewer. The artist, who traveled to the Japanese city to shoot a soft drink commercial, would stay ten days in Kyoto. Sukita’s photos here depict him performing everyday gestures: talking on the phone inside a booth, standing in the subway, wandering among the stalls of a fish market, making

With a jump of about twenty years we come to the last section, with shots covering a rather long time span (ranging from the late 1980s to the 2000s). Arousing the most interest is, again, a David Bowie caught in an intimate and private dimension. One shot, in particular, portrays him looking straight ahead, and especially with an unshaven beard: the singer did not like too much to be seen with a beard that was not well shaved (he did not feel completely comfortable), and here he is captured by Sukita during a moment of relaxation, almost in surprise. The photograph, however, came out so well that it could not fail to be published.

It is on these black-and-white portraits, in some of which David Bowie also appears elegantly dressed in dark suits, that the exhibition concludes. There are many tributes that have been dedicated, around Italy and beyond, to this great artist, who passed away in January. The La Spezia exhibition has many good reasons to stand out. First, since in such a small exhibition (there are about forty photographs) it is impossible to give an exhaustive account of David Bowie’s career, it becomes necessary to choose interesting stories to tell, and David Bowie & Masayoshi Sukita: Heroes has chosen a few particularly interesting moments, achieving a result that skillfully blends two key junctures in Bowie’s career(Ziggy Stardust and Heroes, although the latter appears to be treated much more hastily than the glam period) with a decidedly more intimate narrative that gets us into the heart of the relationship between the singer and the photographer. Second: the point of view of Masayoshi Sukita, a photographer who worked with David Bowie for more than forty years (and thus knows him like few others) is one of the best ways to get intimate with the genius of the British artist. Third, even if the exhibition loses some of its strength in the finale, the layout is still well structured, and it is accompanied by good, effective and easy-to-read (though sometimes a bit evasive) apparatus. It is therefore an exhibition to be visited: both by those who liked and appreciate David Bowie, and by those who do not know him and want to get an idea. An idea that will be, moreover, well comforted by the songs that are played in the rooms of the exhibition as background, and which constitute a really pleasant plus .

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.